Chapter 25: Carboxylic Acids and Esters

Organic and Biochemistry Supplement to Enhanced Introductory College Chemistry

by Gregory Anderson; Jen Booth; Caryn Fahey; Adrienne Richards; Samantha Sullivan Sauer; and David Wegman

Chapter 25 Contents

- 25.1 Carboxylic Acids: Structures and Naming

- 25.2 Physical Properties of Carboxylic Acids

- 25.3 Formation and Reactions of Carboxylic Acids

- 25.4 Ionization and Neutralization of Carboxylic Acids

- 25.5 Esters: Structures, Properties and Naming

- 25.6 Reactions of Esters

- Chapter 25 – Summary

- Chapter 25 – Review

- Chapter 25 – Infographic descriptions

Except where otherwise noted, this OER is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Please visit the web version of Organic and Biochemistry Supplement to Enhanced Introductory College Chemistry to access the complete book, interactive activities and ancillary resources.

In this chapter, you will learn about:

- Carboxylic acids: what are they? What is their chemical structure? What are the physical and chemical properties of these acids?

- Esters: what are they? What is their chemical structure? What are the physical and chemical properties of esters?

To better support your learning, you should be familiar with the following concepts before starting this chapter:

- Alkanes, Alkenes, and Alkynes (Chapter 20: Alkanes and Akyl Halides and Chapter 22: Alkenes, Alkynes and Aromatics)

- Alcohols and Ethers (Chapter 23: Alcohols and Ethers)

- Aldehydes and Ketones (Chapter 24: Aldehydes and Ketones)

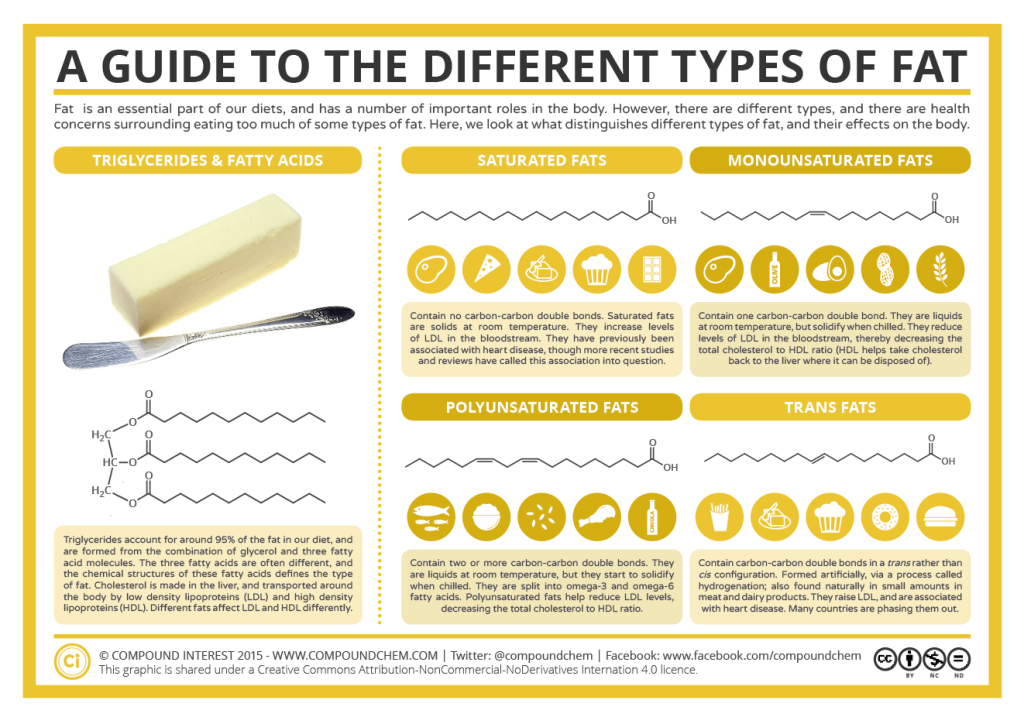

- Functional Groups (Chapter 19.5: Families of Organic Molecules)

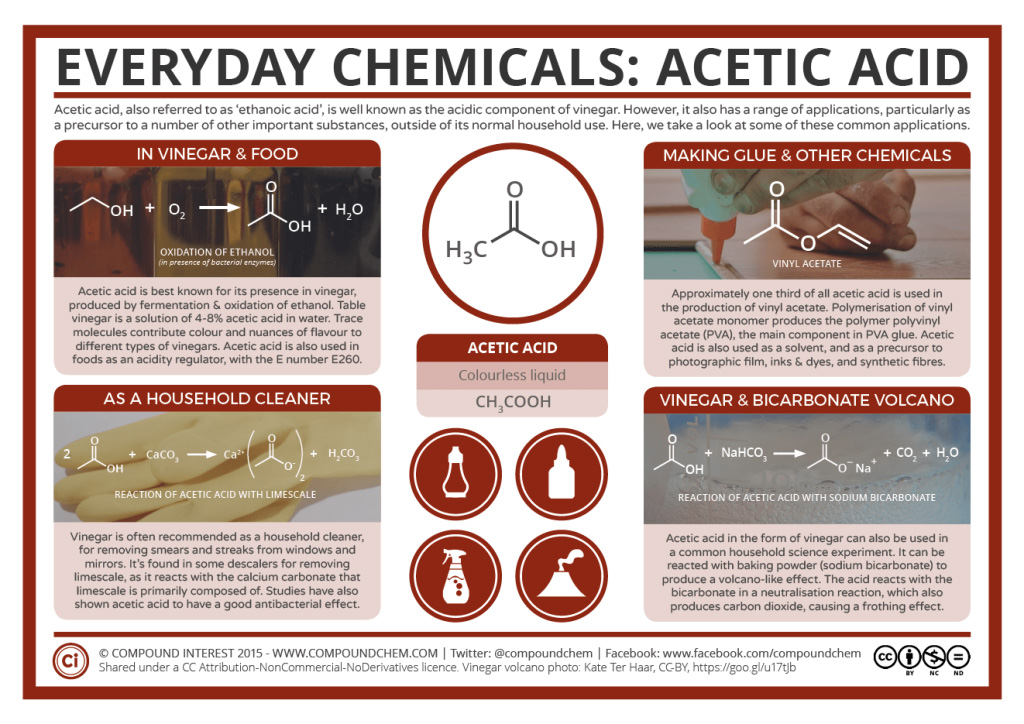

Organic acids have been known for ages. Prehistoric people likely made acetic acid when their fermentation reactions went awry and produced vinegar instead of wine. The Sumerians (2900–1800 BCE) used vinegar as a condiment, a preservative, an antibiotic, and a detergent. Citric acid was discovered by an Islamic alchemist, Jabir Ibn Hayyan (also known as Geber), in the 8th century, and crystalline citric acid was first isolated from lemon juice in 1784 by the Swedish chemist Carl Wilhelm Scheele. Medieval scholars in Europe were aware that the crisp, tart flavour of citrus fruits is caused by citric acid. Naturalists of the 17th century knew that the sting of a red ant’s bite was due to an organic acid that the ant injected into the wound. The acetic acid of vinegar (inforgraphic 25.0b), the formic acid of red ants, and the citric acid of fruits all belong to the same family of compounds—carboxylic acids. Soaps are salts of long-chain carboxylic acids. Prehistoric people also knew about organic bases—by smell if not by name; amines are the organic bases produced when animal tissue decays. The organic compounds that we consider in this chapter are carboxylic acids. Soaps are salts of long-chain carboxylic acids. We will also discuss esters which are derived from a carboxylic acid and an alcohol. Fats and oils are esters (see infographic 25.0a.), as are many important fragrances and flavours. The structure of these fats will differ based on the presence of at least one double bond within the carbon chain.

Spotlight on Everyday Chemistry: Acetic Acid

Acetic acid is a common carboxylic acid which is commonly used in cooking and cleaning practices. Due to its flavour and acidic properties it can be used to regulate the acidity in foods we eat. It is also found to have good antibacterial properties and therefore makes a great household cleaning solution.

Attribution & References

- Except where otherwise noted, this page is adapted by Caryn Fahey from “15.0: Prelude to Organic Acids and Bases and Some of Their Derivatives” In Basics of General, Organic, and Biological Chemistry (Ball et al.) by David W. Ball, John W. Hill, and Rhonda J. Scott via LibreTexts, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0./ A LibreTexts version of Introduction to Chemistry: GOB (v. 1.0), CC BY-NC 3.0.