17.8 Real World Examples of Equilibria

Learning Objectives

- Describe examples of systems involving two (or more) simultaneous chemical equilibria

- Calculate reactant and product concentrations for multiple equilibrium systems

- Compare dissolution and weak electrolyte formation

There are times when one equilibrium reaction does not adequately describe the system being studied. Sometimes we have more than one type of equilibrium occurring at once (for example, an acid-base reaction and a precipitation reaction).

The ocean is a unique example of a system with multiple equilibria, or multiple states of solubility equilibria working simultaneously. Carbon dioxide in the air dissolves in sea water, forming carbonic acid (H2CO3). The carbonic acid then ionizes to form hydrogen ions and bicarbonate ions (HCO3–), which can further ionize into more hydrogen ions and carbonate ions (CO32-):

[latex]\begin{array}{rl @{{}\rightleftharpoons{}} l} \text{CO}_2(g) \rightleftharpoons & \text{CO}_2(aq) \\[0.5em] \text{CO}_2(aq)\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}(l) \rightleftharpoons & \text{H}_2\text{CO}_3(aq) \\[0.5em] \text{H}_2\text{CO}_3(aq) \rightleftharpoons & \text{H}^{+}(aq)\;+\;\text{HCO}_3^{\;\;-}(aq) \\[0.5em] \text{HCO}_3^{\;\;-}(aq) \rightleftharpoons & \text{H}^{+}(aq)\;+\;\text{CO}_3^{\;\;2-}(aq) \end{array}[/latex]

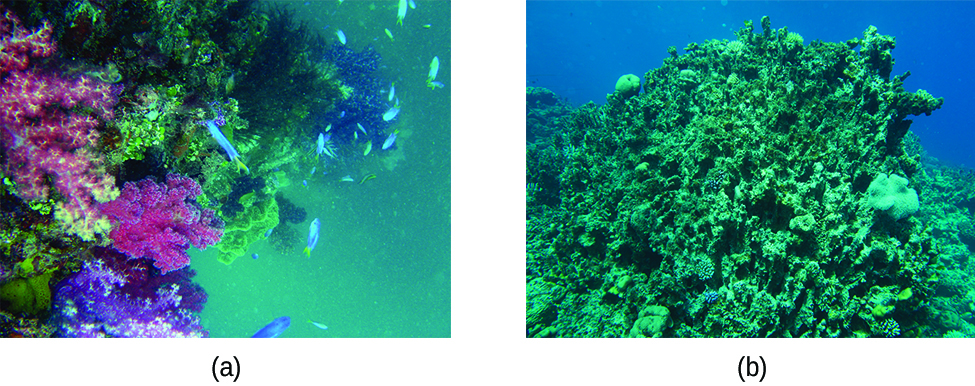

The excess H+ ions make seawater more acidic. Increased ocean acidification can then have negative impacts on reef-building coral, as they cannot absorb the calcium carbonate they need to grow and maintain their skeletons (Figure 17.7a). This in turn disrupts the local biosystem that depends upon the health of the reefs for its survival. If enough local reefs are similarly affected, the disruptions to sea life can be felt globally. The world’s oceans are presently in the midst of a period of intense acidification, believed to have begun in the mid-nineteenth century, and which is now accelerating at a rate faster than any change to oceanic pH in the last 20 million years.

Video Source: Birch Aquarium at Scripps. (2016, March 9). Can corals cope with ocean acidification? [Video]. YouTube.

Slightly soluble solids derived from weak acids generally dissolve in strong acids, unless their solubility products are extremely small. For example, we can dissolve CuCO3, FeS, and Ca3(PO4)2 in HCl because their basic anions react to form weak acids (H2CO3, H2S, and H2PO4–). The resulting decrease in the concentration of the anion results in a shift of the equilibrium concentrations to the right in accordance with Le Châtelier’s principle.

Of particular relevance to us is the dissolution of hydroxylapatite, Ca5(PO4)3OH, in acid. Apatites are a class of calcium phosphate minerals (Figure 17.7b); a biological form of hydroxylapatite is found as the principal mineral in the enamel of our teeth. A mixture of hydroxylapatite and water (or saliva) contains an equilibrium mixture of solid Ca5(PO4)3OH and dissolved Ca2+, PO43-, and OH– ions:

When exposed to acid, phosphate ions react with hydronium ions to form hydrogen phosphate ions and ultimately, phosphoric acid:

[latex]\begin{array}{rl @{{}\rightleftharpoons{}} l} \text{PO}_4^{\;\;3-}(aq)\;+\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+} \rightleftharpoons & \text{H}_2\text{PO}_4^{\;\;2-}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O} \\[0.5em] \text{PO}_4^{\;\;2-}(aq)\;+\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+} \rightleftharpoons & \text{H}_2\text{PO}_4^{\;\;-}\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O} \\[0.5em] \text{H}_2\text{PO}_4^{\;\;-}\;+\;\text{H}_3\text{O}^{+} \rightleftharpoons & \text{H}_3\text{PO}_4\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O} \end{array}[/latex]

Hydroxide ion reacts to form water:

These reactions decrease the phosphate and hydroxide ion concentrations, and additional hydroxylapatite dissolves in an acidic solution in accord with Le Châtelier’s principle. Our teeth develop cavities when acid waste produced by bacteria growing on them causes the hydroxylapatite of the enamel to dissolve. Fluoride toothpastes contain sodium fluoride, NaF, or stannous fluoride [more properly named tin(II) fluoride], SnF2. They function by replacing the OH– ion in hydroxylapatite with F– ion, producing fluorapatite, Ca5(PO4)3F:

The resulting Ca5(PO4)3F is slightly less soluble than Ca5(PO4)3OH, and F– is a weaker base than OH–. Both of these factors make the fluorapatite more resistant to attack by acids than hydroxylapatite. See the Chemistry in Everyday Life feature on the role of fluoride in preventing tooth decay for more information.

Role of Fluoride in Preventing Tooth Decay

As we saw previously, fluoride ions help protect our teeth by reacting with hydroxylapatite to form fluorapatite, Ca5(PO4)3F. Since it lacks a hydroxide ion, fluorapatite is more resistant to attacks by acids in our mouths and is thus less soluble, protecting our teeth. Scientists discovered that naturally fluorinated water could be beneficial to your teeth, and so it became common practice to add fluoride to drinking water. Toothpastes and mouthwashes also contain amounts of fluoride (Figure 17.7c).

Unfortunately, excess fluoride can negate its advantages. Natural sources of drinking water in various parts of the world have varying concentrations of fluoride, and places where that concentration is high are prone to certain health risks when there is no other source of drinking water. The most serious side effect of excess fluoride is the bone disease, skeletal fluorosis. When excess fluoride is in the body, it can cause the joints to stiffen and the bones to thicken. It can severely impact mobility and can negatively affect the thyroid gland. Skeletal fluorosis is a condition that over 2.7 million people suffer from across the world. So while fluoride can protect our teeth from decay, the US Environmental Protection Agency sets a maximum level of 4 ppm (4 mg/L) of fluoride in drinking water in the US. Fluoride levels in water are not regulated in all countries, so fluorosis is a problem in areas with high levels of fluoride in the groundwater.

When acid rain attacks limestone or marble, which are calcium carbonates, a reaction occurs that is similar to the acid attack on hydroxylapatite. The hydronium ion from the acid rain combines with the carbonate ion from calcium carbonates and forms the hydrogen carbonate ion, a weak acid:

Calcium hydrogen carbonate, Ca(HCO3)2, is soluble, so limestone and marble objects slowly dissolve in acid rain.

If we add calcium carbonate to a concentrated acid, hydronium ion reacts with the carbonate ion according to the equation:

(Acid rain is usually not sufficiently acidic to cause this reaction; however, laboratory acids are.) The solution may become saturated with the weak electrolyte carbonic acid, which is unstable, and carbon dioxide gas can be evolved:

These reactions decrease the carbonate ion concentration, and additional calcium carbonate dissolves. If enough acid is present, the concentration of carbonate ion is reduced to such a low level that the reaction quotient for the dissolution of calcium carbonate remains less than the solubility product of calcium carbonate, even after all of the calcium carbonate has dissolved.

Example 17.8a

Prevention of Precipitation of Mg(OH)2

Calculate the concentration of ammonium ion that is required to prevent the precipitation of Mg(OH)2 in a solution with [Mg2+] = 0.10 M and [NH3] = 0.10 M.

Solution

Two equilibria are involved in this system:

Reaction (1): [latex]\text{Mg(OH)}_2(s)\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{Mg}^{2+}(aq)\;+\;2\text{ OH}^{-}(aq)\text{;}\;\;\;\;\;\;\;K_{\text{sp}} = 8.9\;\times\;10^{-12}[/latex]

Reaction (2): [latex]\text{NH}_3(aq)\;+\;\text{H}_2\text{O}(l)\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{NH}_4^{\;\;+}(aq)\;+\;\text{OH}^{-}(aq)\;\;\;\;\;\;\;K_{\text{b}} = 1.8\;\times\;10^{-5}[/latex]

To prevent the formation of solid Mg(OH)2, we must adjust the concentration of OH– so that the reaction quotient for Equation (1), Q = [Mg2+][OH–]2, is less than Ksp for Mg(OH)2. (To simplify the calculation, we determine the concentration of OH– when Q = Ksp.) [OH–] can be reduced by the addition of NH4+, which shifts Reaction (2) to the left and reduces [OH–].

- We determine the [OH–] at which Q = Ksp when [Mg2+] = 0.10 M:

[latex]Q = [\text{Mg}^{2+}][\text{OH}^{-}]^2 = (0.10)[\text{OH}^{-}]^2 = 8.9\;\times\;10^{-12}[/latex][latex][\text{OH}^{-}] = 9.4\;\times\;10^{-6}\;M[/latex]

Solid Mg(OH)2 will not form in this solution when [OH–] is less than 1.2 × 10–5M.

- We calculate the [NH4+] needed to decrease [OH–] to 1.2 × 10–5 M when [NH3] = 0.10.

[latex]K_{\text{b}} = \frac{[\text{NH}_4^{\;\;+}][\text{OH}^{-}]}{[\text{NH}_3]} = \frac{[\text{NH}_4^{+}](9.4\;\times\;10^{-6})}{0.10} = 1.8\;\times\;10^{-5}[/latex][latex][\text{NH}_4^{\;\;+}] = 0.19\;M[/latex]

When [NH4+] equals 0.19 M, [OH–] will be 9.4 × 10–6M. Any [NH4+] greater than 0.19 M will reduce [OH–] below 9.4 × 10–6M and prevent the formation of Mg(OH)2.

Therefore, precise calculations of the solubility of solids from the solubility product are limited to cases in which the only significant reaction occurring when the solid dissolves is the formation of its ions. For formation constants for complex ions, see Appendix L.

Example 17.8b

Multiple Equilibria

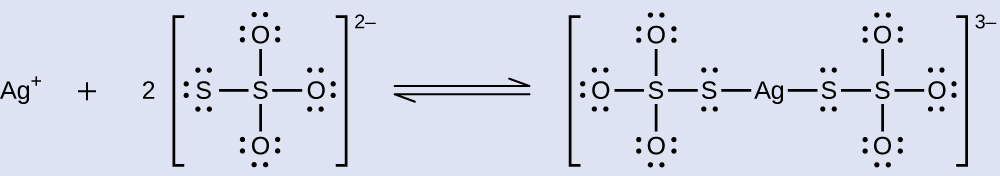

Unexposed silver halides are removed from photographic film when they react with sodium thiosulfate (Na2S2O3) to form the complex ion Ag(S2O3)23- (Kf = 4.7 × 1013). The reaction with silver bromide is:

What mass of Na2S2O3 is required to prepare 1.00 L of a solution that will dissolve 1.00 g of AgBr by the formation of Ag(S2O3)23-?

Solution

Two equilibria are involved when AgBr dissolves in a solution containing the S2O32- ion:

Reaction (1): [latex]\text{AgBr}(s)\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{Ag}^{+}(aq)\;+\;\text{Br}^{-}(aq)\;\;\;\;\;\;\;K_{\text{sp}} = 5.0\;\times\;10^{-13}[/latex]

Reaction (2): [latex]\text{Ag}^{+}(aq)\;+\;2\text{ S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-}(aq)\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{Ag(S}_2\text{O}_3)_2^{\;\;3-}(aq)\;\;\;\;\;\;\;K_{\text{f}} = 4.7\;\times\;10^{13}[/latex]

In order for 1.00 g of AgBr to dissolve, the [Ag+] in the solution that results must be low enough for Q for Reaction (1) to be smaller than Ksp for this reaction. We reduce [Ag+] by adding S2O32- and thus cause Reaction (2) to shift to the right. We need the following steps to determine what mass of Na2S2O3 is needed to provide the necessary S2O32-.

- We calculate the [Br–] produced by the complete dissolution of 1.00 g of AgBr (5.33 ×10–3 mol AgBr) in 1.00 L of solution:

[latex][\text{Br}^{-}] = 5.33\;\times\;10^{-3}\;M[/latex]

- We use [Br–] and Ksp to determine the maximum possible concentration of Ag+ that can be present without causing reprecipitation of AgBr:

[latex][\text{Ag}^{+}] = 9.4\;\times\;10^{-11}\;M[/latex]

- We determine the [S2O32-] required to make [Ag+] = 9.4 ×10–11 M after the remaining Ag+ ion has reacted with S2O32- according to the equation:

[latex]\text{Ag}^{+}\;+\;2\text{ S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-}\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{Ag(S}_2\text{O}_3)_2^{\;\;3-}\;\;\;\;\;\;\;K_{\text{f}} = 4.7\;\times\;10^{13}[/latex]

Because 5.33 × 10–3 mol of AgBr dissolves:

[latex](5.33\;\times\;10^{-3})\;-\;(9.4\;\times\;10^{-11}) = 5.33\;\times\;10^{-3}\;\text{mol\Ag(S}_2\text{O}_3)_2^{\;\;3-}[/latex]Thus, at equilibrium: [Ag(S2O3)23-] = 5.33 × 10–3M, [Ag+] = 9.4 × 10–11M, and Q = Kf = 4.7 × 1013:

[latex]K_{\text{f}} = \frac{[\text{Ag(S}_2\text{O}_3)_2^{\;\;3-}]}{[\text{Ag}^{+}][\text{S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-}]^2} = 4.7\;\times\;10^{13}[/latex][latex][\text{S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-}] = 1.1\;\times\;10^{-3}\;M[/latex]When [S2O32-] is 1.1 × 10–3M, [Ag+] is 9.4 × 10–11M and all AgBr remains dissolved.

- We determine the total number of moles of S2O32- that must be added to the solution. This equals the amount that reacts with Ag+ to form Ag(S2O3)23- plus the amount of free S2O32- in solution at equilibrium. To form 5.33 × 10–3 mol of Ag(S2O3)23- requires 2 × (5.33 × 10–3) mol of S2O32-. In addition, 1.1 × 10–3 mol of unreacted S2O32- is present (Step 3). Thus, the total amount of S2O32- that must be added is:

[latex]2\;\times\;(5.33\;\times\;10^{-3}\;\text{mol\S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-})\;+\;1.1\;\times\;10^{-3}\;\text{mol\S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-} = 1.18\;\times\;10^{-2}\;\text{mol\S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-}[/latex]

- We determine the mass of Na2S2O3 required to give 1.18 × 10–2 mol S2O32- using the molar mass of Na2S2O3:

[latex]1.18\;\times\;10^{-2}\;\text{mol\S}_2\text{O}_3^{\;\;2-}\;\times\;\frac{158.1\;\text{g\Na}_2\text{S}_2\text{O}_3}{1\;\text{mol\Na}_2\text{S}_2\text{O}_3} = 1.9\;\text{g\Na}_2\text{S}_2\text{O}_3[/latex]

Thus, 1.00 L of a solution prepared from 1.9 g Na2S2O3 dissolves 1.0 g of AgBr.

Exercise 17.8a

AgCl(s), silver chloride, is well known to have a very low solubility: [latex]\text{Ag}(s)\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{Ag}^{+}(aq)\;+\;\text{Cl}^{-}(aq)[/latex], Ksp = 1.6 × 10–10. Adding ammonia significantly increases the solubility of AgCl because a complex ion is formed: [latex]\text{Ag}^{+}(aq)\;+\;2\text{ NH}_3(aq)\;{\rightleftharpoons}\;\text{Ag(NH}_3)_2^{\;\;+}(aq)[/latex], Kf = 1.7 × 107. What mass of NH3 is required to prepare 1.00 L of solution that will dissolve 2.00 g of AgCl by formation of Ag(NH3)2+?

Check Your Answer[1]

Dissolution versus Weak Electrolyte Formation

We can determine how to shift the concentration of ions in the equilibrium between a slightly soluble solid and a solution of its ions by applying Le Châtelier’s principle. For example, one way to control the concentration of manganese(II) ion, Mn2+, in a solution is to adjust the pH of the solution and, consequently, to manipulate the equilibrium between the slightly soluble solid manganese(II) hydroxide, manganese(II) ion, and hydroxide ion:

This could be important to a laundry because clothing washed in water that has a manganese concentration exceeding 0.1 mg per litre may be stained by the manganese. We can reduce the concentration of manganese by increasing the concentration of hydroxide ion. We could add, for example, a small amount of NaOH or some other base such as the silicates found in many laundry detergents. As the concentration of OH– ion increases, the equilibrium responds by shifting to the left and reducing the concentration of Mn2+ ion while increasing the amount of solid Mn(OH)2 in the equilibrium mixture, as predicted by Le Châtelier’s principle.

Example 17.8c

Solubility Equilibrium of a Slightly Soluble Solid

What is the effect on the amount of solid Mg(OH)2 that dissolves and the concentrations of Mg2+ and OH– when each of the following are added to a mixture of solid Mg(OH)2 in water at equilibrium?

- MgCl2

- KOH

- an acid

- NaNO3

- Mg(OH)2

Solution

The equilibrium among solid Mg(OH)2 and a solution of Mg2+ and OH– is:

- The reaction shifts to the left to relieve the stress produced by the additional Mg2+ ion, in accordance with Le Châtelier’s principle. In quantitative terms, the added Mg2+ causes the reaction quotient to be larger than the solubility product (Q > Ksp), and Mg(OH)2 forms until the reaction quotient again equals Ksp. At the new equilibrium, [OH–] is less and [Mg2+] is greater than in the solution of Mg(OH)2 in pure water. More solid Mg(OH)2 is present.

- The reaction shifts to the left to relieve the stress of the additional OH– ion. Mg(OH)2 forms until the reaction quotient again equals Ksp. At the new equilibrium, [OH–] is greater and [Mg2+] is less than in the solution of Mg(OH)2 in pure water. More solid Mg(OH)2 is present.

- The concentration of OH– is reduced as the OH– reacts with the acid. The reaction shifts to the right to relieve the stress of less OH– ion. In quantitative terms, the decrease in the OH– concentration causes the reaction quotient to be smaller than the solubility product (Q < Ksp), and additional Mg(OH)2 dissolves until the reaction quotient again equals Ksp. At the new equilibrium, [OH–] is less and [Mg2+] is greater than in the solution of Mg(OH)2 in pure water. More Mg(OH)2 is dissolved.

- NaNO3 contains none of the species involved in the equilibrium, so we should expect that it has no appreciable effect on the concentrations of Mg2+ and OH–. (As we have seen previously, dissolved salts change the activities of the ions of an electrolyte. However, the salt effect is generally small, and we shall neglect the slight errors that may result from it.)

- The addition of solid Mg(OH)2 has no effect on the solubility of Mg(OH)2 or on the concentration of Mg2+ and OH–. The concentration of Mg(OH)2 does not appear in the equation for the reaction quotient:

Thus, changing the amount of solid magnesium hydroxide in the mixture has no effect on the value of Q, and no shift is required to restore Q to the value of the equilibrium constant.

Attribution & References

- 1.00 L of a solution prepared with 4.81 g NH3 dissolves 2.0 g of AgCl. ↵

system characterized by more than one state of balance between a slightly soluble ionic solid and an aqueous solution of ions working simultaneously