9.2 Mole-Mass and Mass-Mass Calculations

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- From a given number of moles of a substance, calculate the mass of another substance involved using the balanced chemical equation

- From a given mass of a substance, calculate the moles of another substance involved using the balanced chemical equation

- From a given mass of a substance, calculate the mass of another substance involved using the balanced chemical equation

Mole-mole calculations are not the only type of calculations that can be performed using balanced chemical equations. Recall that the molar mass can be determined from a chemical formula and used as a conversion factor. We can add that conversion factor as another step in a calculation to make a mole-mass calculation, where we start with a given number of moles of a substance and calculate the mass of another substance involved in the chemical equation, or vice versa.

For example, suppose we have the balanced chemical equation:

2 Al + 3 Cl2 → 2 AlCl3

Suppose we know we have 123.2 g of Cl2. How can we determine how many moles of AlCl3 we will get when the reaction is complete? First and foremost, chemical equations are not balanced in terms of grams; they are balanced in terms of moles. So to use the balanced chemical equation to relate an amount of Cl2 to an amount of AlCl3, we need to convert the given amount of Cl2 into moles. We know how to do this by simply using the molar mass of Cl2 as a conversion factor. The molar mass of Cl2 (which we get from the atomic mass of Cl from the periodic table) is 70.90 g/mol. We must invert this fraction so that the units cancel properly:

[latex]123.2 \cancel{\text{ g }\ce{Cl2}}\times \dfrac{1\text{ mol }\ce{Cl2}}{70.90\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{Cl2}}}=1.738\text{ mol }\ce{Cl2}[/latex]

Now that we have the quantity in moles, we can use the balanced chemical equation to construct a conversion factor that relates the number of moles of Cl2 to the number of moles of AlCl3. The numbers in the conversion factor come from the coefficients in the balanced chemical equation:

[latex]\dfrac{2\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}{3\text{ mol }\ce{Cl2}}[/latex]

Using this conversion factor with the molar quantity we calculated above, we get:

[latex]1.738\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{Cl2}}\times \dfrac{2\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}{3\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{Cl2}}}=1.159\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}[/latex]

So, we will get 1.159 mol of AlCl3 if we react 123.2 g of Cl2.

In this last example, we did the calculation in two steps. However, it is mathematically equivalent to perform the two calculations sequentially on one line:

[latex]123.2\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{Cl2}}\times \dfrac{1\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{Cl2}}}{70.90\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{Cl2}}}\times \dfrac{2\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}{3\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{Cl2}}}=1.159\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}[/latex]

The units still cancel appropriately, and we get the same numerical answer in the end. Sometimes the answer may be slightly different from doing it one step at a time because of rounding of the intermediate answers, but the final answers should be effectively the same.

Example 9.2a

Problem

How many moles of HCl will be produced when 249 g of AlCl3 are reacted according to this chemical equation?

2 AlCl3 + 3 H2O(ℓ) → Al2O3 + 6 HCl(g)

Solution

We will do this in two steps: convert the mass of AlCl3 to moles and then use the balanced chemical equation to find the number of moles of HCl formed. The molar mass of AlCl3 is 133.33 g/mol, which we have to invert to get the appropriate conversion factor:

[latex]1.87\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}\times \dfrac{6\text{ mol }\ce{HCl}}{2\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}}=5.61\text{ mol }\ce{HCl}[/latex]

Now we can use this quantity to determine the number of moles of HCl that will form. From the balanced chemical equation, we construct a conversion factor between the number of moles of AlCl3 and the number of moles of HCl:

[latex]\dfrac{6\text{ mol }\ce{HCl}}{2\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}[/latex]

Applying this conversion factor to the quantity of AlCl3, we get:

[latex]1.87\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}\times \dfrac{6\text{ mol }\ce{HCl}}{2\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}}=5.61\text{ mol }\ce{HCl}[/latex]

Alternatively, we could have done this in one line:

[latex]249\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{AlCl3}}\times \dfrac{1\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}}{133.33\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{AlCl3}}} \times \dfrac{6\text{ mol }\ce{HCl}}{2\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{AlCl3}}} = 5.60\text{ mol }\ce{HCl}[/latex]

The last digit in our final answer is slightly different because of rounding differences, but the answer is essentially the same.

Exercise 9.2a

How many moles of Al2O3 will be produced when 23.9 g of H2O are reacted according to this chemical equation?

2 AlCl3 + 3 H2O(ℓ) → Al2O3 + 6 HCl(g)

Check Your Answer[1]

A variation of the mole-mass calculation is to start with an amount in moles and then determine an amount of another substance in grams. The steps are the same but are performed in reverse order.

Example 9.2b

Problem

How many grams of NH3 will be produced when 33.9 mol of H2 are reacted according to this chemical equation?

N2(g) + 3 H2(g) → 2 NH3(g)

Solution

The conversions are the same, but they are applied in a different order. Start by using the balanced chemical equation to convert to moles of another substance and then use its molar mass to determine the mass of the final substance. In two steps, we have:

[latex]33.9\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{H2}}\times \dfrac{2\text{ mol }\ce{NH3}}{3\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{H2}}}=22.6\text{ mol }\ce{NH3}[/latex]

Now, using the molar mass of NH3, which is 17.03 g/mol, we get:

[latex]22.6\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{NH3}}\times \dfrac{17.03\text{ g }\ce{NH3}}{1\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{NH3}}}=385\text{ g }\ce{NH3}[/latex]

Exercise 9.2b

How many grams of N2 are needed to produce 2.17 mol of NH3 when reacted according to this chemical equation?

N2(g) + 3 H2(g) → 2 NH3(g)

Check Your Answer[2]

It should be a trivial task now to extend the calculations to mass-mass calculations, in which we start with a mass of some substance and end with the mass of another substance in the chemical reaction. For this type of calculation, the molar masses of two different substances must be used - be sure to keep track of which is which. Again, however, it is important to emphasize that before the balanced chemical reaction is used, the mass quantity must first be converted to moles. Then the coefficients of the balanced chemical reaction can be used to convert to moles of another substance, which can then be converted to a mass.

For example, let us determine the number of grams of SO3 that can be produced by the reaction of 45.3 g of SO2 and O2:

2 SO2(g) + O2(g) → 2 SO3(g)

First, we convert the given amount, 45.3 g of SO2, to moles of SO2 using its molar mass (64.06 g/mol):

[latex]45.3\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{SO2}}\times \dfrac{1\text{ mol }\ce{SO2}}{64.06\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{SO2}}}=0.707\text{ mol }\ce{SO2}[/latex]

Second, we use the balanced chemical reaction to convert from moles of SO2 to moles of SO3:

[latex]0.707\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO2}}\times \dfrac{2\text{ mol }\ce{SO3}}{2\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO2}}}=0.707\text{ mol }\ce{SO3}[/latex]

Finally, we use the molar mass of SO3 (80.06 g/mol) to convert to the mass of SO3:

[latex]0.707\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO3}}\times \dfrac{80.06\text{ g }\ce{SO3}}{1\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO3}}}=56.6\text{ g }\ce{SO3}[/latex]

We can also perform all three steps sequentially, writing them on one line as:

[latex]45.3\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{SO2}}\times \dfrac{1\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO2}}}{64.06\cancel{\text{ g }\ce{SO2}}}\times \dfrac{2\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO3}}}{2\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO2}}}\times \dfrac{80.06\text{ g }\ce{SO3}}{1\cancel{\text{ mol }\ce{SO3}}}=56.6\text{ g }\ce{SO3}[/latex]

We get the same answer. Note how the initial and all the intermediate units cancel, leaving grams of SO3, which is what we are looking for, as our final answer.

Example 9.2c

Problem

What mass of Mg will be produced when 86.4 g of K are reacted?

MgCl2(s) + 2 K(s) → Mg(s) + 2 KCl(s)

Solution

We will simply follow the steps:

mass K → mol K → mol Mg → mass Mg

In addition to the balanced chemical equation, we need the molar masses of K (39.09 g/mol) and Mg (24.31 g/mol). In one line,

[latex]86.4\cancel{\text{ g K}}\times \dfrac{1\cancel{\text{ mol K}}}{39.09\cancel{\text{ g K}}}\times \dfrac{1\cancel{\text{ mol Mg}}}{2\cancel{\text{ mol K}}}\times \dfrac{24.31\text{ g Mg}}{1\cancel{\text{ mol Mg}}}=26.87 \text{ Mg}[/latex]

Exercise 9.2c

What mass of H2 will be produced when 122 g of Zn are reacted?

Zn(s) + 2 HCl(aq) → ZnCl2(aq) + H2(g)

Check Your Answer[3]

Example 9.2d

Relating Masses of Reactants and Products

What mass of sodium hydroxide, NaOH, would be required to produce 16 g of the antacid milk of magnesia [magnesium hydroxide, Mg(OH)2] by the following reaction?

Solution

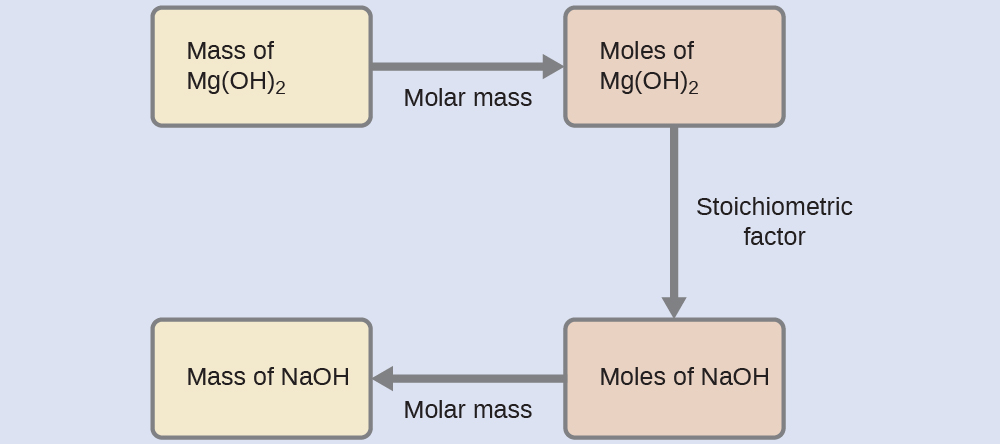

The approach used previously in Example 9.2a and Example 9.2b is likewise used here; that is, we must derive an appropriate stoichiometric factor from the balanced chemical equation and use it to relate the amounts of the two substances of interest. In this case, however, masses (not molar amounts) are provided and requested, so additional steps of the sort learned in the previous chapter are required. The calculations required are outlined in this flowchart:

Exercise 9.2d

What mass of gallium oxide, Ga2O3, can be prepared from 29.0 g of gallium metal? The equation for the reaction is:

[latex]4 \text{Ga} + 3\text{O}_2 \longrightarrow 2\text{Ga}_2 \text{O}_3[/latex]

Check Your Answer[4]

Example 9.2e

Relating Masses of Reactants

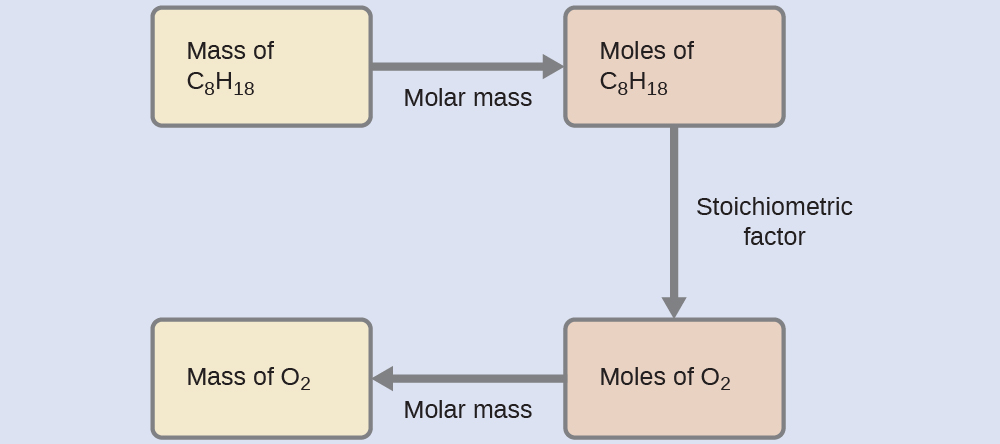

What mass of oxygen gas, O2, from the air is consumed in the combustion of 702 g of octane, C8H18, one of the principal components of gasoline?

Solution

The approach required here is the same as for the Example 3, differing only in that the provided and requested masses are both for reactant species.

Exercise 9.2e

What mass of CO is required to react with 25.13 g of Fe2O3 according to the equation:

[latex]\text{Fe}_2 \text{O}_3 + 3\text{CO} \longrightarrow 2\text{Fe} + 3\text{CO}_2[/latex]

Check Your Answer[5]

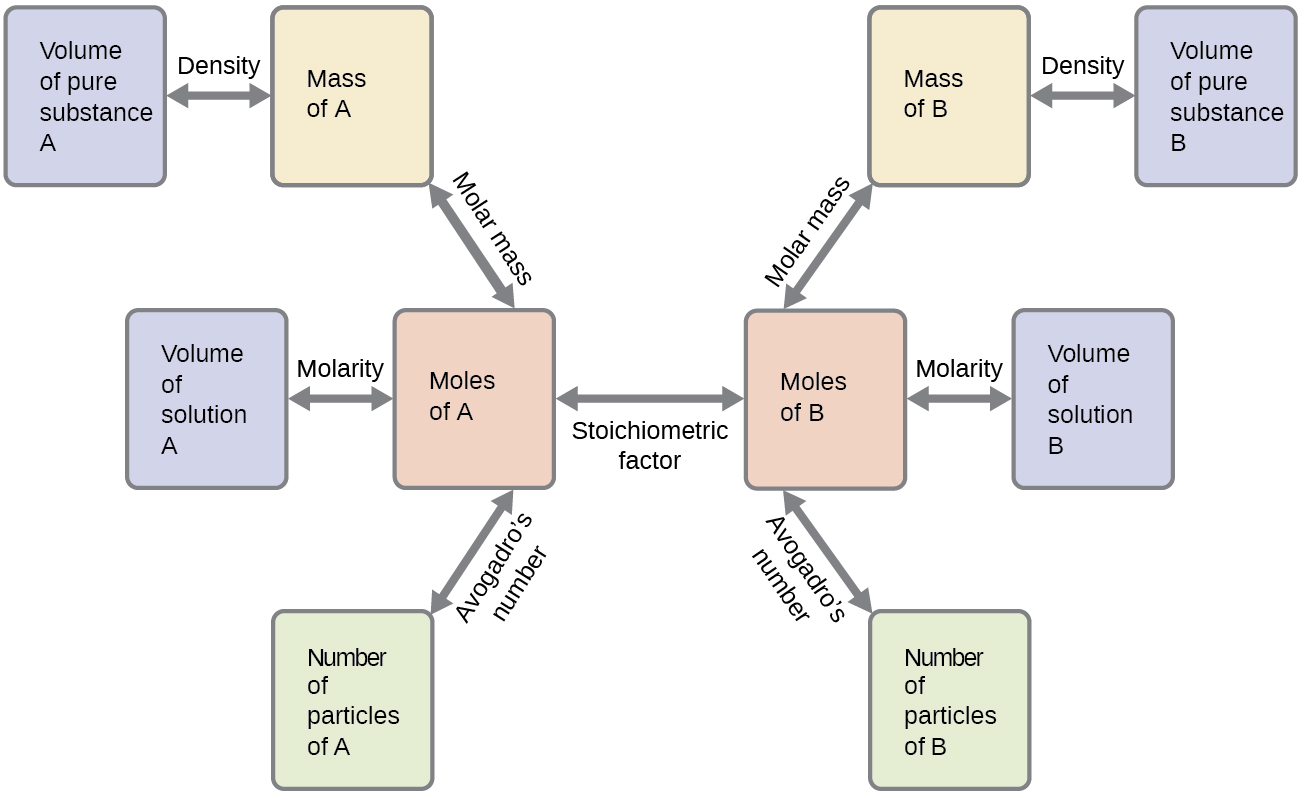

These examples illustrate just a few instances of reaction stoichiometry calculations. Numerous variations on the beginning and ending computational steps are possible depending upon what particular quantities are provided and sought (volumes, solution concentrations, and so forth). Regardless of the details, all these calculations share a common essential component: the use of stoichiometric factors derived from balanced chemical equations. Figure 9.2a provides a general outline of the various computational steps associated with many reaction stoichiometry calculations.

Airbags

Airbags (Figure 9.2b) are a safety feature provided in most automobiles since the 1990s. The effective operation of an airbag requires that it be rapidly inflated with an appropriate amount (volume) of gas when the vehicle is involved in a collision. This requirement is satisfied in many automotive airbag systems through use of explosive chemical reactions, one common choice being the decomposition of sodium azide, NaN3. When sensors in the vehicle detect a collision, an electrical current is passed through a carefully measured amount of NaN3 to initiate its decomposition:

This reaction is very rapid, generating gaseous nitrogen that can deploy and fully inflate a typical airbag in a fraction of a second (~0.03–0.1 s). Among many engineering considerations, the amount of sodium azide used must be appropriate for generating enough nitrogen gas to fully inflate the air bag and ensure its proper function. For example, a small mass (~100 g) of NaN3 will generate approximately 50 L of N2.

Links to Interactive Learning Tools

Practice Stoichiometry - Relationships (all levels) from The Physics Classroom.

Attribution & References

Except where otherwise noted, this page is adapted by Adrienne Richards from:

- "7.3 Reaction Stiochiometry" In General Chemistry 1 & 2 by Rice University, a derivative of Chemistry (Open Stax) by Paul Flowers, Klaus Theopold, Richard Langley & William R. Robinson and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at Chemistry (OpenStax) AND

- "Chapter 5: Stoichiometry and The Mole: Mole-Mass and Mass-Mass Calculations" In Introductory Chemistry: 1st Canadian Edition by David W. Ball and Jessica A. Key, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

A calculation in which you start with a given number of moles of a substance and calculate the mass of another substance involved in the chemical equation, or vice versa.

A calculation in which you start with a given mass of a substance and calculate the mass of another substance involved in the chemical equation.