7.8 – Catalysis

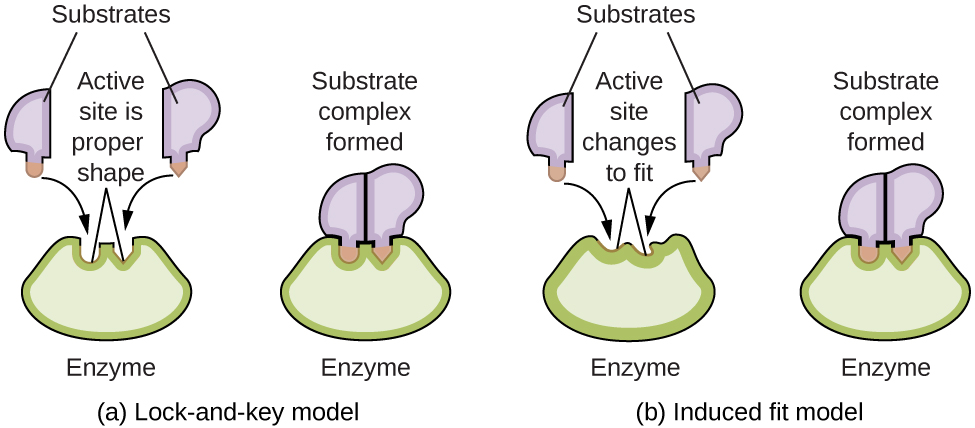

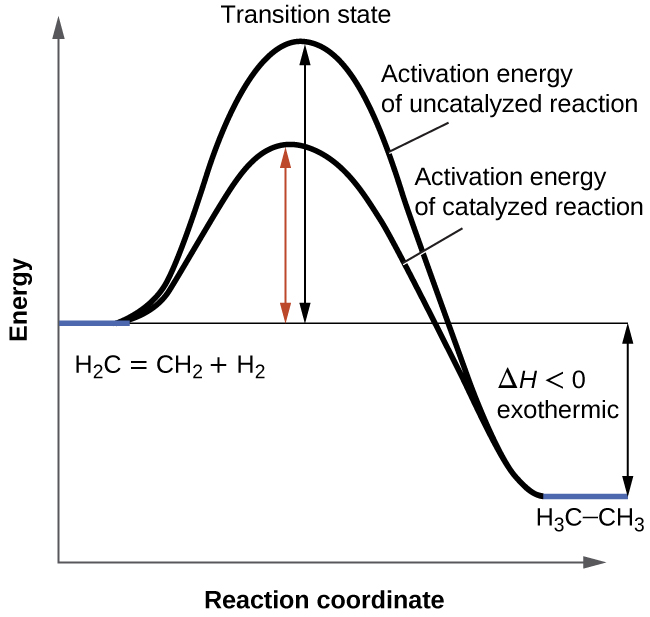

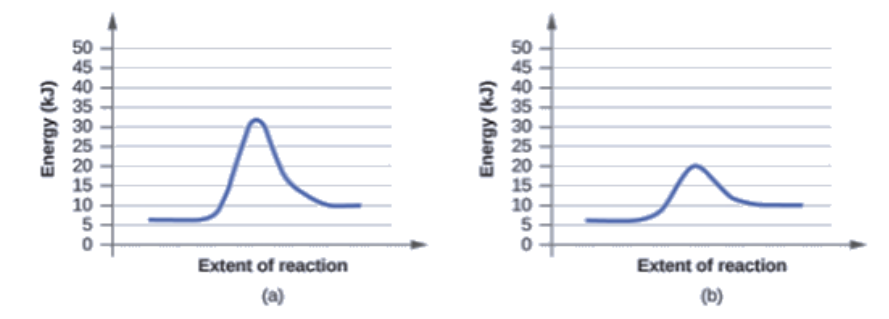

It was introduced in a previous section that the rate of many reactions can be accelerated by catalysts. A catalyst speeds up the rate of a reaction by lowering the activation energy; in addition, the catalyst is regenerated in the process. Several reactions that are thermodynamically favorable in the absence of a catalyst only occur at a reasonable rate when a catalyst is present. One such reaction is catalytic hydrogenation, the process by which hydrogen is added across an alkene C=C bond to afford the saturated alkane product. A comparison of the reaction coordinate diagrams (also known as energy diagrams) for catalyzed and uncatalyzed alkene hydrogenation is shown in Figure 7.8.1.

Figure 7.8.1. This graph compares the reaction coordinates for catalyzed and uncatalyzed alkene hydrogenation.

Reaction coordinate diagrams (also known as reaction profiles) display how a reaction progresses from reactants to products in terms of energy. These diagrams consist of the following elements:

Reaction coordinate on the X-axis: the progression of a reaction from reactants (left) to products (right) for the forward reaction, and vice-versa for the reverse reaction

Energy on the Y-axis: the amount of potential energy present as the reaction proceeds; the lower the potential energy, the more stable the species

Reactants: indicated as the flat line on the far left

Products: indicated as the flat line on the far right

Transition state (activated complex): represents the complex found at the peak of the curve. It is a particular configuration of reactants at the moment of reaction collision(s) that gives a “structure” of maximum potential energy and hence of greatest instability. Note that the transition state is not a defined structure or intermediate.

Activation energy: represented by the difference and rise in potential energy between 1) reactants, products or an intermediate, and 2) the transition state (forward reaction) or between products and the transition state (reverse reaction). It represents the energy barrier that must be overcome to attain the transition state. The system must gain energy and become increasingly unstable to adopt the activated complex; once it is reached, an input of energy is no longer required, and the system decreases in energy and becomes more stable as the reaction proceeds.

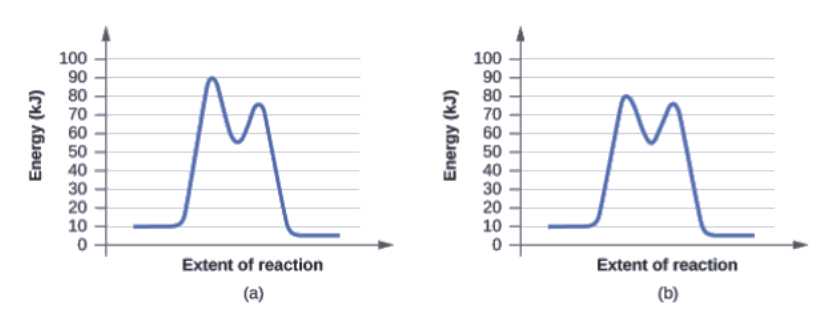

Intermediate (not shown in Figure 7.8.1 but portrayed in the catalyzed pathway of Figure 7.8.2): represents the structure found at the trough of a curve. It is a species that temporarily exists as the product for one step of the reaction and as a reactant for the next step. It has a well-defined chemical structure and is hence more stable than a transition state, but it only persists momentarily so is less stable and higher in energy than both reactants and products.

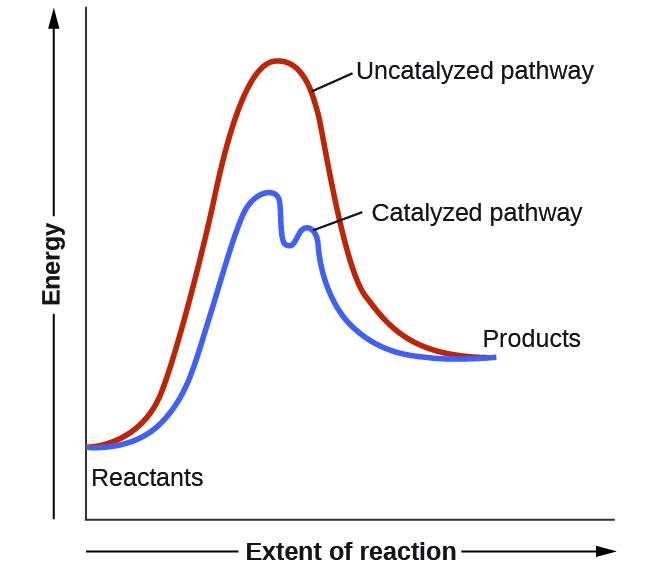

Catalysts function by providing an alternate reaction mechanism that has a lower activation energy than would be found in the absence of the catalyst. In some cases, the catalyzed mechanism may include additional steps, as depicted in the reaction diagrams shown in Figure 7.8.2. This lower activation energy results in an increase in rate as described by the Arrhenius equation. Note that a catalyst decreases the activation energy for both the forward and the reverse reactions and hence accelerates both the forward and the reverse reactions. Consequently, the presence of a catalyst will permit a system to reach equilibrium more quickly, but it has no effect on the position of the equilibrium as reflected in the value of its equilibrium constant (see the previous topic on chemical equilibrium).

Figure 7.8.2. This potential energy diagram shows the effect of a catalyst on the activation energy. The catalyst provides a different reaction path with a lower activation energy. As shown, the catalyzed pathway involves a two-step mechanism (note the presence of two transition states) and an intermediate species (represented by the valley between the two transitions states).

Example 7.8.1 – Using Reaction Diagrams to Compare Catalyzed Reactions

The two reaction diagrams here represent the same reaction: one without a catalyst and one with a catalyst. Identify which diagram suggests the presence of a catalyst, and determine the activation energy for the catalyzed reaction:

Solution

A catalyst does not affect the energy of the reactant or product, so those aspects of the diagrams can be ignored; they are, as we would expect, identical in that respect. There is, however, a noticeable difference in the transition state, which is distinctly lower in energy in diagram (b) than it is in (a). This indicates the use of a catalyst in diagram (b). The activation energy is the difference between the energy of the starting reagents and the transition state—a maximum on the reaction coordinate diagram. The reagents are at 6 kJ and the transition state is at 20 kJ, so the activation energy can be calculated as follows:

Ea = 20 kJ – 6 kJ = 14 kJ

Check Your Learning 7.8.1 – Using Reaction Diagrams to Compare Catalyzed Reactions

Determine which of the two diagrams here (both for the same reaction) involves a catalyst, and identify the activation energy for the catalyzed reaction:

Answer

Diagram (b) is a catalyzed reaction with an activation energy of about 70 kJ.

Homogeneous Catalysts

A homogeneous catalyst is present in the same phase as the reactants. It interacts with a reactant to form an intermediate substance, which then decomposes or reacts with another reactant in one or more steps to regenerate the original catalyst and form product.

As an important illustration of homogeneous catalysis, consider the earth’s ozone layer. Ozone in the upper atmosphere, which protects the earth from ultraviolet radiation, is formed when oxygen molecules absorb ultraviolet light and undergo the reaction:

3O2 (g) hv → 2O3 (g)

Ozone is a relatively unstable molecule that decomposes to yield diatomic oxygen by the reverse of this equation. This decomposition reaction is consistent with the following mechanism:

O3 → O2 + O

O + O3 → 2O2

The presence of nitric oxide, NO, influences the rate of decomposition of ozone. Nitric oxide acts as a catalyst in the following mechanism:

NO (g) + O3 (g) → NO2 (g) + O2 (g)

O3 (g) → O2 (g) + O (g)

NO2 (g) + O (g) → NO (g) + O2 (g)

The overall chemical change for the catalyzed mechanism is the same as:

2O3 (g) → 3O2 (g)

The nitric oxide reacts and is regenerated in these reactions. It is not permanently used up; thus, it acts as a catalyst. The rate of decomposition of ozone is greater in the presence of nitric oxide because of the catalytic activity of NO. Certain compounds that contain chlorine also catalyze the decomposition of ozone.

|

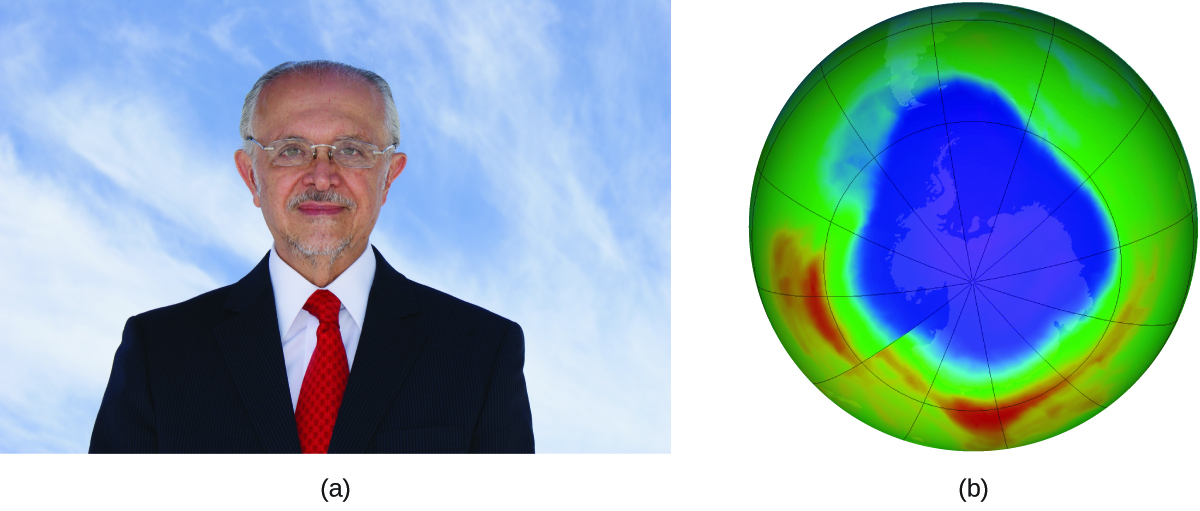

Mario J. Molina The 1995 Nobel Prize in Chemistry was shared by Paul J. Crutzen, Mario J. Molina (Figure 7.8.3.), and F. Sherwood Rowland “for their work in atmospheric chemistry, particularly concerning the formation and decomposition of ozone.”1 Molina, a Mexican citizen, carried out the majority of his work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

Figure 7.8.3. (a) Mexican chemist Mario Molina (1943 –) shared the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995 for his research on (b) the Antarctic ozone hole. (credit a: courtesy of Mario Molina; credit b: modification of work by NASA) In 1974, Molina and Rowland published a paper in the journal Nature (one of the major peer-reviewed publications in the field of science) detailing the threat of chlorofluorocarbon gases to the stability of the ozone layer in earth’s upper atmosphere. The ozone layer protects earth from solar radiation by absorbing ultraviolet light. As chemical reactions deplete the amount of ozone in the upper atmosphere, a measurable “hole” forms above Antarctica, and an increase in the amount of solar ultraviolet radiation— strongly linked to the prevalence of skin cancers—reaches earth’s surface. The work of Molina and Rowland was instrumental in the adoption of the Montreal Protocol, an international treaty signed in 1987 that successfully began phasing out production of chemicals linked to ozone destruction. Molina and Rowland demonstrated that chlorine atoms from human-made chemicals can catalyze ozone destruction in a process similar to that by which NO accelerates the depletion of ozone. Chlorine atoms are generated when chlorocarbons or chlorofluorocarbons—once widely used as refrigerants and propellants—are photochemically decomposed by ultraviolet light or react with hydroxyl radicals. A sample mechanism is shown here using methyl chloride: CH3Cl + OH → Cl + other products Chlorine radicals break down ozone and are regenerated by the following catalytic cycle: Cl + O3 → ClO + O2 ClO + O → Cl + O2 overall Reaction: O3 + O → 2O2 A single monatomic chlorine can break down thousands of ozone molecules. Luckily, the majority of atmospheric chlorine exists as the catalytically inactive forms Cl2 and ClONO2. Since receiving his portion of the Nobel Prize, Molina has continued his work in atmospheric chemistry at MIT. 1 The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1995. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1995/summary/ |

|

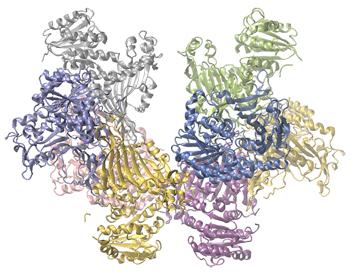

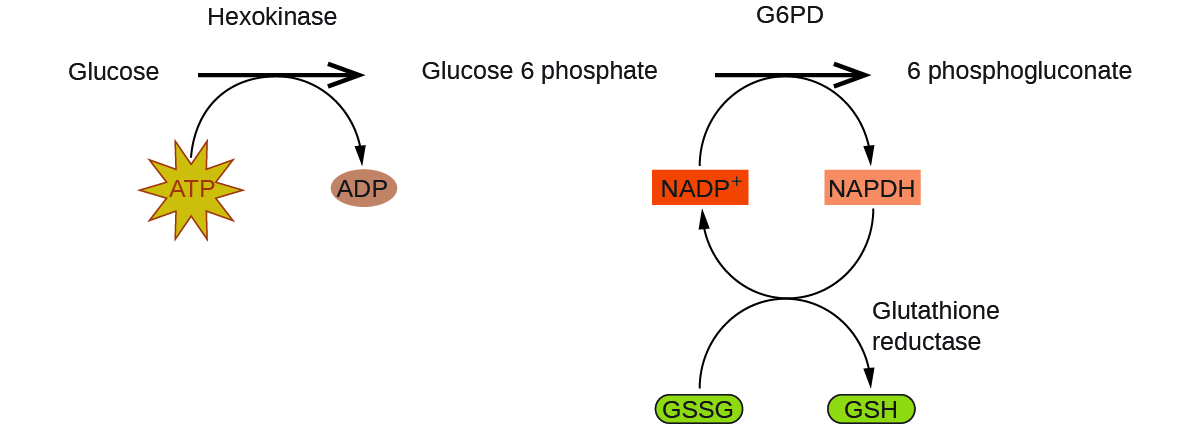

Glucose-6-Phosphate Dehydrogenase Deficiency Enzymes in the human body act as catalysts for important chemical reactions in cellular metabolism. As such, a deficiency of a particular enzyme can translate to a life-threatening disease. G6PD (glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase) deficiency, a genetic condition that results in a shortage of the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, is the most common enzyme deficiency in humans. This enzyme, shown in Figure 7.8.4., is the rate-limiting enzyme for the metabolic pathway that supplies NADPH to cells (Figure 7.8.4.).

Figure 7.8.4. Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase is a rate-limiting enzyme for the metabolic pathway that supplies NADPH to cells. A disruption in this pathway can lead to reduced glutathione in red blood cells; once all glutathione is consumed, enzymes and other proteins such as hemoglobin are susceptible to damage. For example, hemoglobin can be metabolized to bilirubin, which leads to jaundice, a condition that can become severe. People who suffer from G6PD deficiency must avoid certain foods and medicines containing chemicals that can trigger damage to their glutathione-deficient red blood cells.

Figure 7.8.5. In the mechanism for the pentose phosphate pathway, G6PD catalyzes the reaction that regulates NAPDH, a co-enzyme that regulates glutathione, an antioxidant that protects red blood cells and other cells from oxidative damage.

|

Heterogeneous Catalysts

A heterogeneous catalyst is a catalyst that is present in a different phase (usually a solid) than the reactants. Such catalysts generally function by furnishing an active surface upon which a reaction can occur. Gas and liquid phase reactions catalyzed by heterogeneous catalysts occur on the surface of the catalyst rather than within the gas or liquid phase.

Heterogeneous catalysis has at least four steps:

Adsorption of the reactant onto the surface of the catalyst

Activation of the adsorbed reactant

Reaction of the adsorbed reactant

Diffusion of the product from the surface into the gas or liquid phase (desorption).

Any one of these steps may be slow and thus may serve as the rate determining step. In general, however, in the presence of the catalyst, the overall rate of the reaction is faster than it would be if the reactants were in the gas or liquid phase.

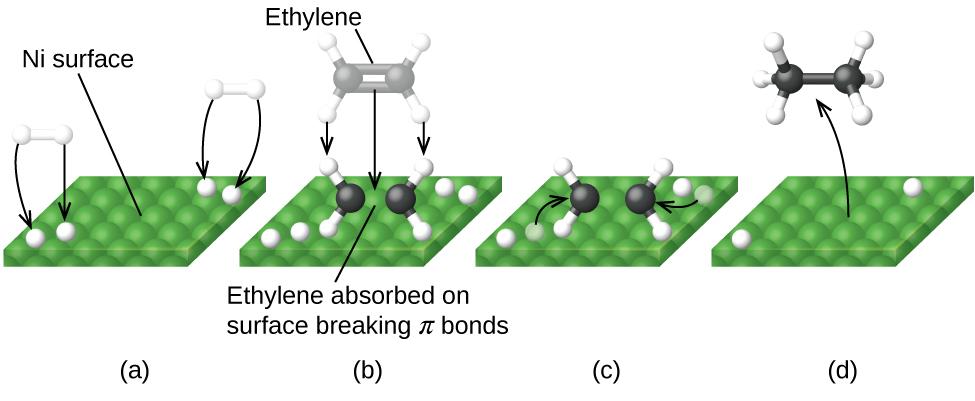

Figure 7.8.6. illustrates the steps that chemists believe to occur in the reaction of compounds containing a carbon–carbon double bond with hydrogen on a nickel catalyst. Nickel is the catalyst used in the hydrogenation of polyunsaturated fats and oils (which contain several carbon–carbon double bonds) to produce saturated fats and oils (which contain only carbon–carbon single bonds).

Figure 7.8.6. There are four steps in the catalysis of the reaction CdH4 + H2 ⟶ C2H6 by nickel. (a) Hydrogen is adsorbed on the surface, breaking the H–H bonds and forming Ni–H bonds. (b) Ethylene is adsorbed on the surface, breaking the π-bond and forming Ni–C bonds. (c) Atoms diffuse across the surface and form new C–H bonds when they collide. (d) C2H6 molecules escape from the nickel surface, since they are not strongly attracted to nickel.

|

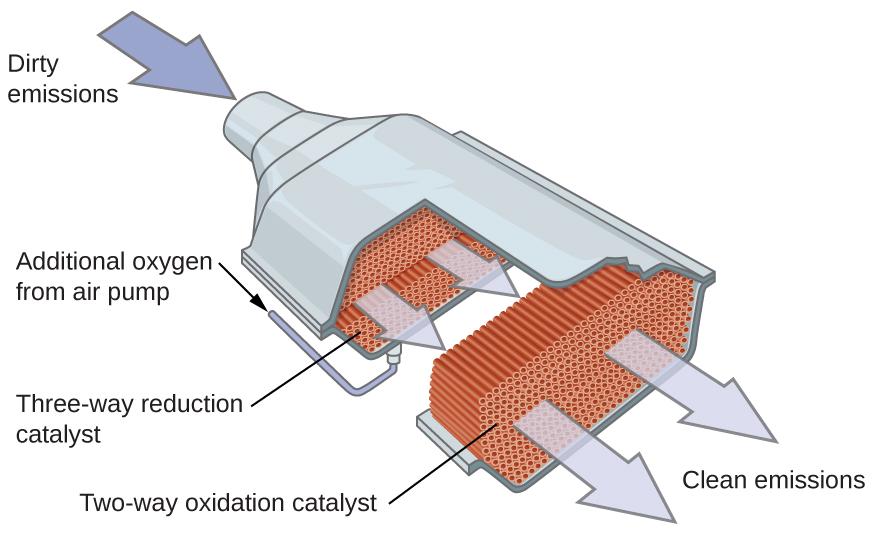

Automobile Catalytic Converters Scientists developed catalytic converters to reduce the amount of toxic emissions produced by burning gasoline in internal combustion engines. Catalytic converters take advantage of all five factors that affect the speed of chemical reactions to ensure that exhaust emissions are as safe as possible. By utilizing a carefully selected blend of catalytically active metals, it is possible to effect complete combustion of all carbon-containing compounds to carbon dioxide while also reducing the output of nitrogen oxides. This is particularly impressive when we consider that one step involves adding more oxygen to the molecule and the other involves removing the oxygen (Figure 7.8.7.).

Figure 7.8.7. A catalytic converter allows for the combustion of all carbon-containing compounds to carbon dioxide, while at the same time reducing the output of nitrogen oxide and other pollutants in emissions from gasoline-burning engines. Most modern, three-way catalytic converters possess a surface impregnated with a platinum-rhodium catalyst, which catalyzes the conversion of nitric oxide into nitrogen and oxygen as well as the conversion of carbon monoxide and hydrocarbons such as octane into carbon dioxide and water vapor: 2NO2 (g) → N2 (g) + 2O2 (g) 2CO (g) + O2 (g) → 2CO2 (g) 2C8H18 (g) + 25 O2 (g) → 16CO2 (g) + 18H2O (g) In order to be as efficient as possible, most catalytic converters are preheated by an electric heater. This ensures that the metals in the catalyst are fully active even before the automobile exhaust is hot enough to maintain appropriate reaction temperatures. The University of California at Davis’ “ChemWiki” provides a thorough explanation of how catalytic converters work. |

|

Enzyme Structure and Function The study of enzymes is an important interconnection between biology and chemistry. Enzymes are usually proteins (polypeptides) that help to control the rate of chemical reactions between biologically important compounds, particularly those that are involved in cellular metabolism. Different classes of enzymes perform a variety of functions, as shown in the table below. Classes of Enzymes and Their Functions Class Functions oxidoreductases redox reactions transferases transfer of functional groups hydrolases hydrolysis reactions lyases group elimination to form double bonds isomerases isomerization ligases bond formation with ATP hydrolysis Enzyme molecules possess an active site, a part of the molecule with a shape that allows it to bond to a specific substrate (a reactant molecule), forming an enzyme-substrate complex as a reaction intermediate. There are two models that attempt to explain how this active site works. The most simplistic model is referred to as the lock-and-key hypothesis, which suggests that the molecular shapes of the active site and substrate are complementary, fitting together like a key in a lock. The induced fit hypothesis, on the other hand, suggests that the enzyme molecule is flexible and changes shape to accommodate a bond with the substrate. This is not to suggest that an enzyme’s active site is completely malleable, however. Both the lock-and-key model and the induced fit model account for the fact that enzymes can only bind with specific substrates, since in general a particular enzyme only catalyzes a particular reaction (Figure 7.8.8.).

Figure 7.8.8. (a) According to the lock-and-key model, the shape of an enzyme’s active site is a perfect fit for the substrate. (b) According to the induced fit model, the active site is somewhat flexible, and can change shape in order to bond with the substrate. |

The Royal Society of Chemistry provides an excellent introduction to enzymes for students and teachers.

|

CHM1311 Laboratory | Experiment #5: A Kinetic Study: Catalase |

|

Purpose This experiment will look at the kinetics of reactions in the context of catalysts – substances that speed up the rate of reactions by lowering the activation energy. Some catalysts exist as compounds, such as potassium iodide (KI) while others are biological proteins which are found in living organisms – these biological catalysts are referred to as enzymes In the first part of this experiment, you’ll be investigating the catalyzed decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by the enzyme catalase in lettuce. Your job is to design and carry out experiments to determine the partial order with respect to hydrogen peroxide in the rate law: rate = k [H2O2]x [catalase]y In part two of your experiment, you’ll again need to design and carry out an experimental procedure to determine and compare the activation energies of catalase-catalyzed and iodide-catalyzed (from potassium iodide) decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. With this information, you can deduce which of the two catalysts is more efficient in accelerating the rate of reaction. Principles Initial reaction rate Order of the reaction Activation energy Safety Precautions Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) at all times in the laboratory setting – this includes your lab coat and safety goggles/glasses. Be sure to consult the MSDS for H2O2(aq), KI and catalase for relevant health and safety, first aid, handling, and waste disposal information. As you plan your procedure, always make sure that all steps are safe and follow lab safety guidelines. Your TA will verify your procedure before you conduct your experiment. Make sure you don’t confuse the reactants – check the label of each reagent you add when preparing the mixture. Things to Consider Make sure you go through the pre-lab exercise for the experiment – it will allow you to review your knowledge of chemical kinetics, better understand your task and give you a good idea of how to plan your experiment. In your report, make sure you fully detail your experimental procedures. You’ll need to provide the data you collected, analyze it and discuss your results. Make sure your conclusions respond to the two tasks asked of you. The experimental instructions provided to you on Brightspace gives an extensive list of questions and things to consider as you plan your experiment and before you carry out your lab protocol. Make sure you go through and cover these points in your experimental procedure – this will help you better plan your experiment and allow you to be well-prepared before coming into the lab. Reference Venkateswaran, R. General Chemistry – Laboratory Manual – CHM 1301/1311. |

Used in chemical kinetics to illustrate the progression and various properties of a reaction

Used in chemical kinetics to illustrate the progression and various properties of a reaction

Catalyst present in the same phase as the reactants

Catalyst present in a different phase from one or more of the reactants (e.g. furnishing a surface at which a reaction can occur)