7.5 – Collision Theory

We should not be surprised that atoms, molecules, or ions must collide prior to reacting. Atoms must be close together to form chemical bonds. This simple premise is the basis for a very powerful theory that explains many observations regarding chemical kinetics, including factors affecting reaction rates.

Collision theory is based on the following postulates:

1) The rate of a reaction is proportional to the rate of reactant collisions:

2) The reacting species must collide in an orientation that allows contact between the atoms that will become bonded together in the product.

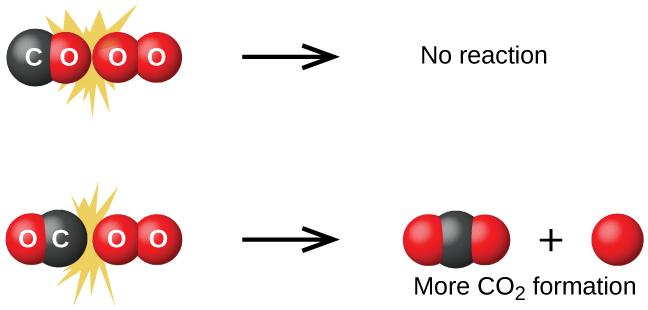

The first step in the gas-phase reaction between carbon monoxide and oxygen is a collision between the two molecules:

Although there are many different possible orientations the two molecules can have relative to each other, consider the two presented in Figure 7.5.1. In the first case, the oxygen side of the carbon monoxide molecule collides with the oxygen molecule. In the second case, the carbon side of the carbon monoxide molecule collides with the oxygen molecule. The second case is clearly more likely to result in the formation of carbon dioxide, which has a central carbon atom bonded to two oxygen atoms (O=C=O). This is a rather simple example of how important the orientation of the collision is in terms of creating the desired product of the reaction.

Figure 7.5.1. Illustrated are two collisions that might take place between carbon monoxide and oxygen molecules. The orientation of the colliding molecules partially determines whether a reaction between the two molecules will occur.

If the collision does take place with the correct orientation, there is still no guarantee that the reaction will proceed to form carbon dioxide. Every reaction requires a certain amount of activation energy for it to proceed in the forward direction, yielding an appropriate activated complex along the way. As Figure 7.5.2. demonstrates, even a collision with the correct orientation can fail to form the reaction product. In the study of reaction mechanisms, each of these three arrangements of atoms is called a proposed activated complex or transition state.

O = C •••O = O

O•••C•••O = O

O = C •••O•••O

Figure 7.5.2. Possible transition states (activated complexes) for carbon monoxide reacting with oxygen to form carbon dioxide. Solid lines represent covalent bonds, while dotted lines represent unstable orbital overlaps that may, or may not, become covalent bonds as the product is formed. In the first two examples in this figure, the O=O double bond is not impacted; therefore, carbon dioxide cannot form. The third proposed transition state will result in the formation of carbon dioxide if the third “extra” oxygen atom separates from the rest of the molecule.

In most circumstances, it is impossible to isolate or identify a transition state or activated complex. In the reaction between carbon monoxide and oxygen to form carbon dioxide, activated complexes have only been observed spectroscopically in systems that utilize a heterogeneous catalyst. The gas-phase reaction occurs too rapidly to isolate any such chemical compound.

Collision theory explains why most reaction rates increase as concentrations increase. With an increase in the concentration of any reacting substance, the chances for collisions between molecules are increased because there are more molecules per unit of volume. More collisions mean a faster reaction rate, assuming the energy of the collisions is adequate.

Activation Energy and the Arrhenius Equation

The minimum energy necessary to form a product during a collision between reactants is called the activation energy (Ea). The kinetic energy of reactant molecules plays an important role in a reaction because the energy necessary to form a product is provided by a collision of a reactant molecule with another reactant molecule. (In single-reactant reactions, activation energy may be provided by a collision of the reactant molecule with the wall of the reaction vessel or with molecules of an inert contaminant.) If the activation energy is much larger than the average kinetic energy of the molecules, the reaction will occur slowly: Only a few fast-moving molecules will have enough energy to react. If the activation energy is much smaller than the average kinetic energy of the molecules, the fraction of molecules possessing the necessary kinetic energy will be large; most collisions between molecules will result in reaction, and the reaction will occur rapidly.

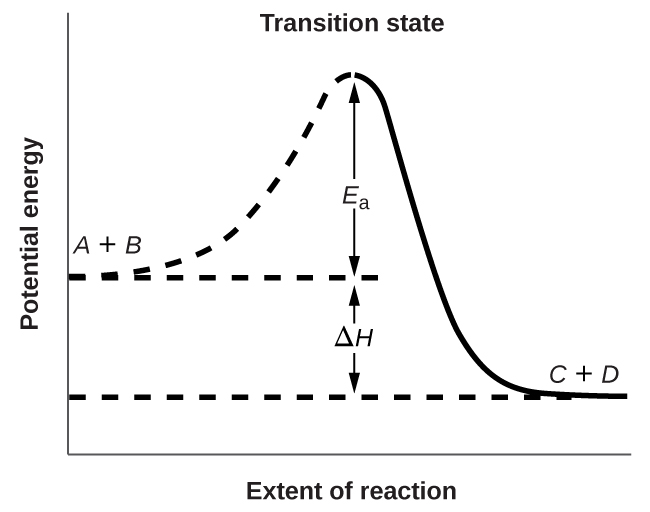

Figure 7.5.3. shows the energy relationships for the general reaction of a molecule of A with a molecule of B to form molecules of C and D:

The figure shows that the energy of the transition state is higher than that of the reactants A and B by an amount equal to Ea, the activation energy. Thus, the sum of the kinetic energies of A and B must be equal to or greater than Ea to reach the transition state. After the transition state has been reached, and as C and D begin to form, the system loses energy until its total energy is lower than that of the initial mixture. This lost energy is transferred to other molecules, giving them enough energy to reach the transition state. The forward reaction (that between molecules A and B) therefore tends to take place readily once the reaction has started. In Figure 7.5.3., ΔH represents the difference in enthalpy between the reactants (A and B) and the products (C and D). The sum of Ea and ΔH represents the activation energy for the reverse reaction:

Figure 7.5.3. This graph shows the potential energy relationships for the reaction A + B ⟶ C + D. The dashed portion of the curve represents the energy of the system with a molecule of A and a molecule of B present, and the solid portion the energy of the system with a molecule of C and a molecule of D present. The activation energy for the forward reaction is represented by Ea. The activation energy for the reverse reaction is greater than that for the forward reaction by an amount equal to ΔH. The curve’s peak is represented the transition state.

We can use the Arrhenius equation to relate the activation energy and the rate constant, k, of a given reaction:

Equation 7.5.1 Arrhenius Equation

In this equation, R is the ideal gas constant, which has a value 8.314 J/mol/K, T is temperature on the Kelvin scale, Ea is the activation energy in joules per mole, e is the natural exponential function with an approximate value 2.7183, and A is a constant called the pre-exponential factor (A), which is related to the frequency of collisions and the orientation of the reacting molecules.

Both postulates of the collision theory of reaction rates are accommodated in the Arrhenius equation. The pre-exponential factor A is related to the rate at which collisions having the correct orientation occur. The exponential term, e−Ea/RT, is related to the fraction of collisions providing adequate energy to overcome the activation barrier of the reaction.

At one extreme, the system does not contain enough energy for collisions to overcome the activation barrier. In such cases, no reaction occurs. At the other extreme, the system has so much energy that every collision with the correct orientation can overcome the activation barrier, causing the reaction to proceed. In such cases, the reaction is nearly instantaneous.

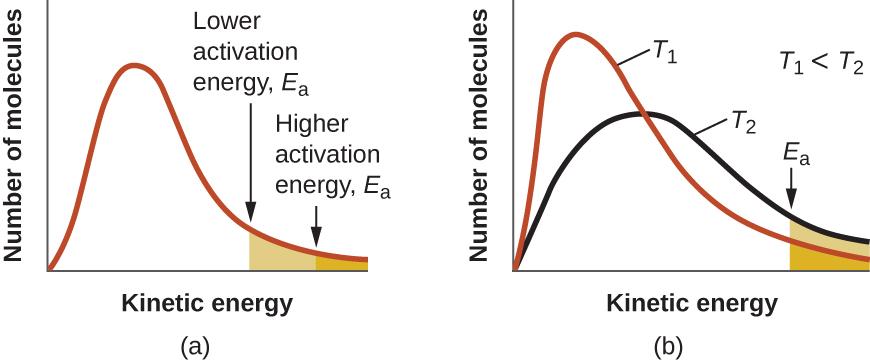

The Arrhenius equation describes quantitatively much of what we have already discussed about reaction rates. For two reactions at the same temperature, the reaction with the higher activation energy has the lower rate constant and the slower rate. The larger value of Ea results in a smaller value for e−Ea/RT, reflecting the smaller fraction of molecules with enough energy to react. Alternatively, the reaction with the smaller Ea has a larger fraction of molecules with enough energy to react. This will be reflected as a larger value of e−Ea/RT, a larger rate constant, and a faster rate for the reaction. An increase in temperature has the same effect as a decrease in activation energy. A larger fraction of molecules has the necessary energy to react (Figure 7.5.4.), as indicated by an increase in the value of e−Ea/RT. The rate constant is also directly proportional to the pre-exponential factor, A. Hence a change in conditions or reactants that increases the number of collisions with a favorable orientation for reaction results in an increase in A and, consequently, an increase in k.

Figure 7.5.4. (a) As the activation energy of a reaction decreases, the number of molecules with at least this much energy increases, as shown by the shaded areas. (b) At a higher temperature, T2, more molecules have kinetic energies greater than Ea, as shown by the yellow shaded area.

A convenient approach to determining Ea for a reaction involves the measurement of k at different temperatures and using of an alternate version of the Arrhenius equation that takes the form of a linear equation:

Thus, a plot of ln k versus 1T gives a straight line with the slope -EaR, from which Ea may be determined. The intercept gives the value of ln A.

Example 7.5.1 – Determination of Ea

The variation of the rate constant with temperature for the decomposition of HI (g) to H2 (g) and I2 (g) is given here. What is the activation energy for the reaction?

|

T (K) |

K (L/mol/s) |

|

555 |

3.52 × 10−7 |

|

575 |

1.22 × 10−6 |

|

645 |

8.59 × 10−5 |

|

700 |

1.16 × 10−3 |

|

781 |

3.95 × 10−2 |

Solution

Values of 1T and ln k are:

|

1T

(K-1) |

ln k |

|

1.80 × 10−3 |

-14.860 |

|

1.74 × 10−3 |

-13.617 |

|

1.55 × 10−3 |

-9.362 |

|

1.43 × 10−3 |

-6.759 |

|

1.28 × 10−3 |

-3.231 |

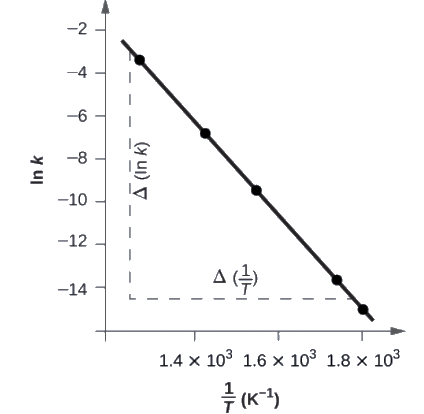

Figure 7.5.5. is a graph of ln k versus 1T. To determine the slope of the line, we need two values of ln k, which are determined from the line at two values of 1T (one near each end of the line is preferable). For example, the value of ln k determined from the line when 1T = 1.25 × 10−3 is −2.593; the value when 1T = 1.78 × 10−3 is −14.447.

Figure 7.5.5. This graph shows the linear relationship between ln k and 1T

for the reaction 2HI ⟶ H2 + I2 according to the Arrhenius equation.

The slope of this line is given by the following expression:

Thus:

In many situations, it is possible to obtain a reasonable estimate of the activation energy without going through the entire process of constructing the Arrhenius plot. The Arrhenius equation:

ln k = (-EaR)(1T) + ln A

can be rearranged as shown to give:

Or

This equation can be rearranged to give a one-step calculation to obtain an estimate for the activation energy:

Ea = -R (lnk2 – lnk1 (1T2 – 1T1))

Using the experimental data presented here, we can simply select two data entries. For this example, we select the first entry and the last entry:

|

T (K) |

k (L/mol/s) |

1T (K-1)

|

ln k |

|

555 |

3,52 × 10−7 |

1,80 × 10−3 |

−14,860 |

|

781 |

3,95 × 10−2 |

1,28 × 10−3 |

−3,231 |

After calculating 1T and ln k, we can substitute into the equation:

Ea = -8.314 Jmol-1K-1 (-3.231 – (-14.860) 1.28 × 10-3K-1 -1.80 × 10-3K-1) and the result is Ea = 185,900 J/mol.

This method is very effective, especially when a limited number of temperature-dependent rate constants are available for the reaction of interest.

Check Your Learning 7.5.2 – Determination of Ea

The rate constant for the rate of decomposition of N2O5 to NO and O2 in the gas phase is 1.66 L/mol/s at 650 K and 7.39 L/mol/s at 700 K:

Assuming the kinetics of this reaction are consistent with the Arrhenius equation, calculate the activation energy for this decomposition.

Answer

113,000 J/mol

Questions

★ Questions

Chemical reactions occur when reactants collide. What are two factors that may prevent a collision from producing a chemical reaction?

What is the activation energy of a reaction, and how is this energy related to the activated complex of the reaction?

When every collision between reactants leads to a reaction, what determines the rate at which the reaction occurs?

Describe how graphical methods can be used to determine the activation energy of a reaction from a series of data that includes the rate of reaction at varying temperatures.

How does an increase in temperature affect the rate of reaction? Explain this effect in terms of the collision theory of the reaction rate.

The rate of a certain reaction doubles for every 10 °C rise in temperature.

How much faster does the reaction proceed at 45 °C than at 25 °C?

How much faster does the reaction proceed at 95 °C than at 25 °C?

★★ Questions

An elevated level of the enzyme alkaline phosphatase (ALP) in the serum is an indication of possible liver or bone disorder. The level of serum ALP is so low that it is very difficult to measure directly. However, ALP catalyzes a number of reactions, and its relative concentration can be determined by measuring the rate of one of these reactions under controlled conditions. One such reaction is the conversion of p-nitrophenyl phosphate (PNPP) to p-nitrophenoxide ion (PNP) and phosphate ion. Control of temperature during the test is very important; the rate of the reaction increases 1.47 times if the temperature changes from 30 °C to 37 °C. What is the activation energy (in kJ/mol) for the ALP–catalyzed conversion of PNPP to PNP and phosphate?

Hydrogen iodide, HI, decomposes in the gas phase to produce hydrogen, H2, and iodine, I2. The value of the rate constant, k, for the reaction was measured at several different temperatures and the data are shown here. What is the value of the activation energy (in kJ/mol) for this reaction

|

Temperature (K) |

k (M-1 s-1) |

|

555 |

6,23 x 10 -7

|

|

575 |

2,42 x 10 -6

|

|

645 |

1,44 x 10 -4

|

|

700 |

2,01 x 10 -3

|

Answers

The reactants either may be moving too slowly to have enough kinetic energy to exceed the activation energy for the reaction, or the orientation of the molecules when they collide may prevent the reaction from occurring.

The activation energy is the minimum amount of energy necessary to form the activated complex in a reaction. It is usually expressed as the energy necessary to form one mole of activated complex.

Order of reaction and concentration

After finding k at several different temperatures, a plot of ln k versus 1/T, gives a straight line with the slope −Ea/R from which Ea may be determined.

When temperature is increased the overall average velocity of particles increases as well. As a result, the kinetic energy will increase allowing for particles to collide more frequently together. With more collisions, the rate of the reaction will also increase.

(a) 4-times faster (b) 128-times faster

43.0 kJ/mol

177 kJ/mol

Model that emphasizes the energy and orientation of molecular collisions in chemical reactions to explain and predict reaction kinetics

Unstable combination of reactant species formed during a chemical reaction; corresponds to the highest energy transitional point in the elementary step

unstable combination of reactant species formed during a chemical reaction; corresponds to the highest energy transitional point in the elementary step

Minimum amount of kinetic energy molecules must possess in order for an effective collision to occur and for a reaction to take place

Mathematical relationship between a reaction’s rate constant, activation energy, and temperature

Proportionality constant in the Arrhenius equation, related to the relative number of collisions having an orientation capable of leading to product formation