2.1 – Intermolecular Forces

The States of Matter

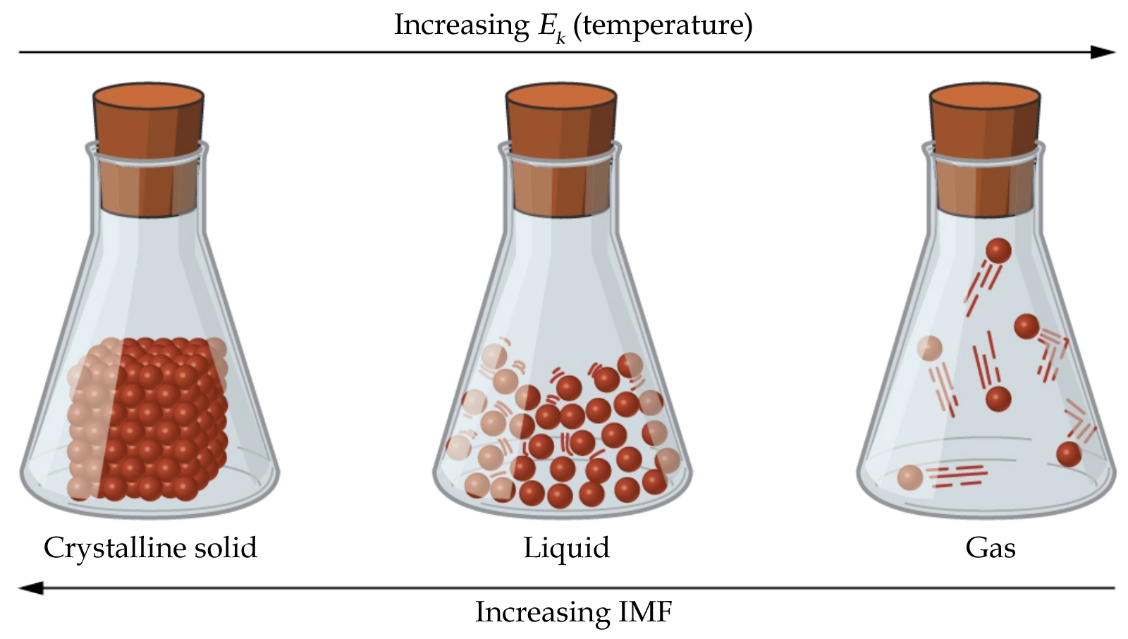

The differences in the properties of a solid, liquid, or gas reflect the strengths of the attractive forces between the atoms, molecules, or ions that make up each phase. The phase in which a substance exists depends on the relative extents of its intermolecular forces (IMFs) and the kinetic energies (Ek) of its molecules. IMFs are the various forces of attraction that may exist between the atoms and molecules of a substance due to electrostatic phenomena, as will be detailed in this module. These forces serve to hold particles close together, whereas the particles’ Ek provides the energy required to overcome the attractive forces and thus increase the distance between particles. Figure 2.1.1 illustrates how changes in physical state may be induced by changing the temperature, hence, the average Ek, of a given substance.

Figure 2.1.1. Transitions between solid, liquid, and gaseous states of a substance occur when conditions of temperature or pressure favor the associated changes in intermolecular forces. (Note: The space between particles in the gas phase is much greater than shown.)

As an example of the processes depicted in Figure 2.1.1, consider a sample of water. When gaseous water is cooled sufficiently, the attractions between H2O molecules will be capable of holding them together when they come into contact with each other; the gas condenses, forming liquid H2O. For example, liquid water forms on the outside of a cold glass as the water vapour in the air is cooled by the cold glass, as seen in Figure 2.1.2.

Figure 2.1.2. Condensation forms when water vapour in the air is cooled enough to form liquid water, such as (a) on the outside of a cold beverage glass or (b) in the form of fog. (credit a: modification of work by Jenny Downing; credit b: modification of work by Cory Zanker)

We can also liquefy many gases by compressing them, if the temperature is not too high. Decreasing the volume results in increased pressure which brings the molecules of a gas closer together, such that the attractions between the molecules become strong relative to their Ek. Consequently, they form liquids. Butane, C4H10, is the fuel used in disposable lighters and is a gas at standard temperature and pressure.

We define Standard Temperature and Pressure (STP) for gases as 0 °C and 1.00 bar (1 bar = 100 000 Pa = 0.987 atm) to establish convenient conditions for comparing the molar volumes of gases. Inside the lighter’s fuel compartment, the butane is compressed to a pressure that results in its condensation to the liquid state, as shown in Figure 2.1.3.

Figure 2.1.3. Gaseous butane is compressed within the storage compartment of a disposable lighter, resulting in its condensation to the liquid state. (credit: modification of work by “Sam-Cat”/Flickr)

Finally, if the temperature of a liquid becomes sufficiently low, or the pressure on the liquid becomes sufficiently high, the molecules of the liquid no longer have enough Ek to overcome the attractive IMF between them, and a solid forms. A more thorough discussion of these and other changes of state, or phase transitions, is provided in a later section of this chapter.

Forces Between Molecules

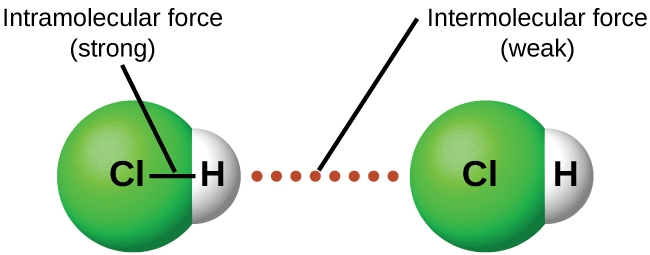

Under appropriate conditions, the attractions between all gas molecules will cause them to form liquids or solids. This is due to intermolecular forces, not intramolecular forces. Intramolecular forces are those within the molecule that keep the molecule together, for example, the bonds between the atoms. Intermolecular forces are the attractions between molecules, which determine many of the physical properties of a substance. Figure 2.1.4 illustrates these different molecular forces. The strengths of these attractive forces vary widely, though usually the IMFs between small molecules are weak compared to the intramolecular forces that bond atoms together within a molecule. For example, to overcome the IMFs in one mole of liquid HCl and convert it into gaseous HCl requires only about 17 kilojoules of energy. However, to break the covalent bonds between the hydrogen and chlorine atoms in one mole of HCl requires about 25 times more energy: 430 kilojoules.

Figure 2.1.4. Intramolecular forces keep a molecule intact. Intermolecular forces hold multiple molecules together and determine many of a substance’s properties.

All of the attractive forces between neutral atoms and molecules are known as van der Waals forces, although they are usually referred to more informally as intermolecular attraction. We will consider the various types of IMFs in the next three sections of this module.

Dispersion Forces

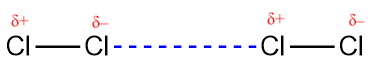

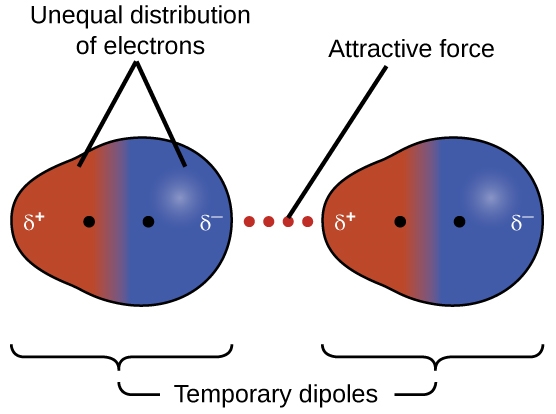

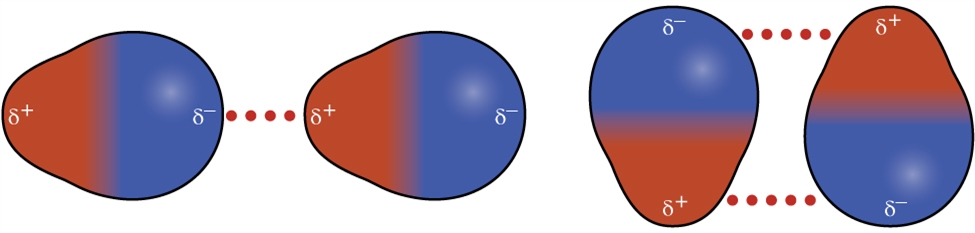

One of the three van der Waals forces is present in all condensed phases, regardless of the nature of the atoms or molecules composing the substance. This attractive force is called the London dispersion force in honour of German-born American physicist Fritz London who, in 1928, first explained it. This force is often referred to as simply the dispersion force. Because the electrons of an atom or molecule are in constant motion (or, alternatively, the electron’s location is subject to quantum-mechanical variability), at any moment in time, an atom or molecule can develop a temporary, instantaneous dipole if its electrons are distributed asymmetrically. Dipoles are present in molecules where there is an unequal dispersion of charge. If there is increased electron density on one end of the molecule, we would label this area with a delta minus (δ–). This then means that the other end of the molecule has a decreased electron density therefore, it is labelled with a delta plus (δ+). These labels are shown in Figure 2.1.5. The presence of this dipole can, in turn, distort the electrons of a neighboring atom or molecule, producing an induced dipole. These two rapidly fluctuating, temporary dipoles thus result in a relatively weak electrostatic attraction between the species—a so-called dispersion force like that illustrated in Figure 2.1.5.

Figure 2.1.5. Dispersion forces result from the formation of temporary dipoles, as illustrated here for two nonpolar diatomic molecules.

Dispersion forces that develop between atoms in different molecules can attract the two molecules to each other. The forces are relatively weak, however, and become significant only when the molecules are very close. Larger and heavier atoms and molecules exhibit stronger dispersion forces than do smaller and lighter atoms and molecules. F2 and Cl2 are gases at room temperature (reflecting weaker attractive forces); Br2 is a liquid, and I2 is a solid (reflecting stronger attractive forces). Trends in observed melting and boiling points for the halogens clearly demonstrate this effect, as seen in the following table.

Table 2.1.1. Melting and Boiling Points of the Halogens

|

Halogen |

Molar Mass |

Atomic Radius |

Melting Point |

Boiling Point |

|

fluorine, F2 |

38 g/mol |

72 pm |

53 K |

85 K |

|

chlorine, Cl2 |

71 g/mol |

99 pm |

172 K |

238 K |

|

bromine, Br2 |

160 g/mol |

114 pm |

266 K |

332 K |

|

iodine, I2 |

254 g/mol |

133 pm |

387 K |

457 K |

|

astatine, At2 |

420 g/mol |

150 pm |

575 K |

610 K |

The increase in melting and boiling points with increasing atomic/molecular size may be rationalized by considering how the strength of dispersion forces is affected by the electronic structure of the atoms or molecules in the substance. In a larger atom, the valence electrons are, on average, farther from the nuclei than in a smaller atom. Thus, they are less tightly held and can more easily form the temporary dipoles that produce the attraction. The measure of how easy or difficult it is for another electrostatic charge (for example, a nearby ion or polar molecule) to distort a molecule’s charge distribution (its electron cloud) is known as polarizability. A molecule that has a charge cloud that is easily distorted is said to be very polarizable and will have large dispersion forces; one with a charge cloud that is difficult to distort is not very polarizable and will have small dispersion forces.

Example 2.1.1 – London Forces and Their Effects

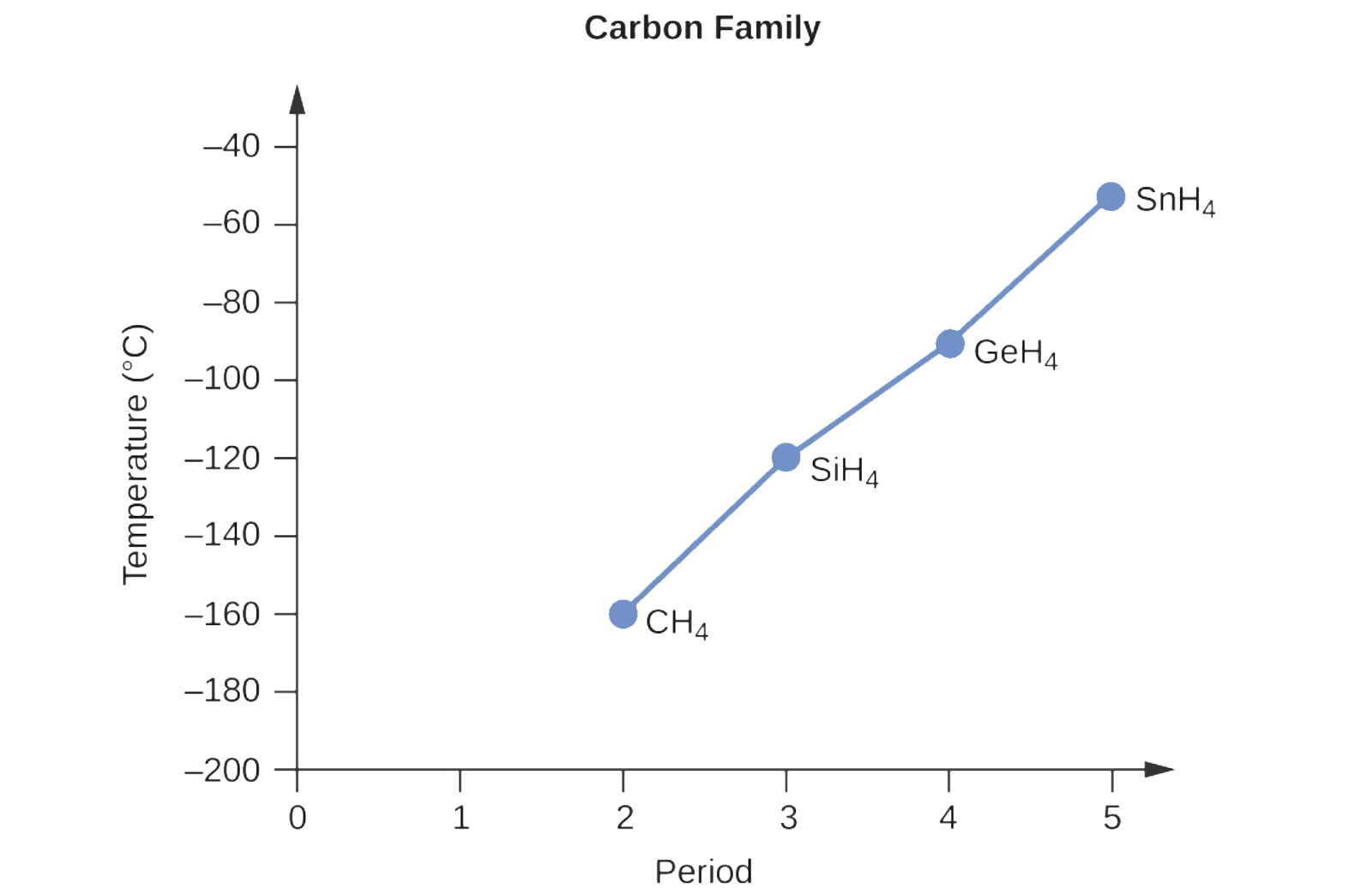

Order the following compounds of a group 14 element and hydrogen from lowest to highest boiling point: CH4, SiH4, GeH4, and SnH4. Explain your reasoning.

Solution

You may recall chemical bonding and molecular geometry from high school chemistry. All of these compounds are predicted to be nonpolar, so they may experience only dispersion forces: the smaller the molecule, the less polarizable and the weaker the dispersion forces; the larger the molecule, the larger the dispersion forces. The molar masses of CH4, SiH4, GeH4, and SnH4 are approximately 16 g/mol, 32 g/mol, 77 g/mol, and 123 g/mol, respectively. Therefore, CH4 is expected to have the lowest boiling point and SnH4 the highest boiling point. The ordering from lowest to highest boiling point is expected to be CH4 < SiH4 < GeH4 < SnH4.

A graph of the actual boiling points of these compounds versus the period of the group 14 element shows this prediction to be correct:

Check Your Learning 2.1.1 – London Forces and Their Effects

Order the following hydrocarbons from lowest to highest boiling point:

C2H6, C3H8, and C4H10.

Answer

C2H6 < C3H8 < C4H10. All of these compounds are nonpolar and only have London dispersion forces: the larger the molecule, the larger the dispersion forces and the higher the boiling point. The ordering from lowest to highest boiling point is therefore C2H6 < C3H8 < C4H10.

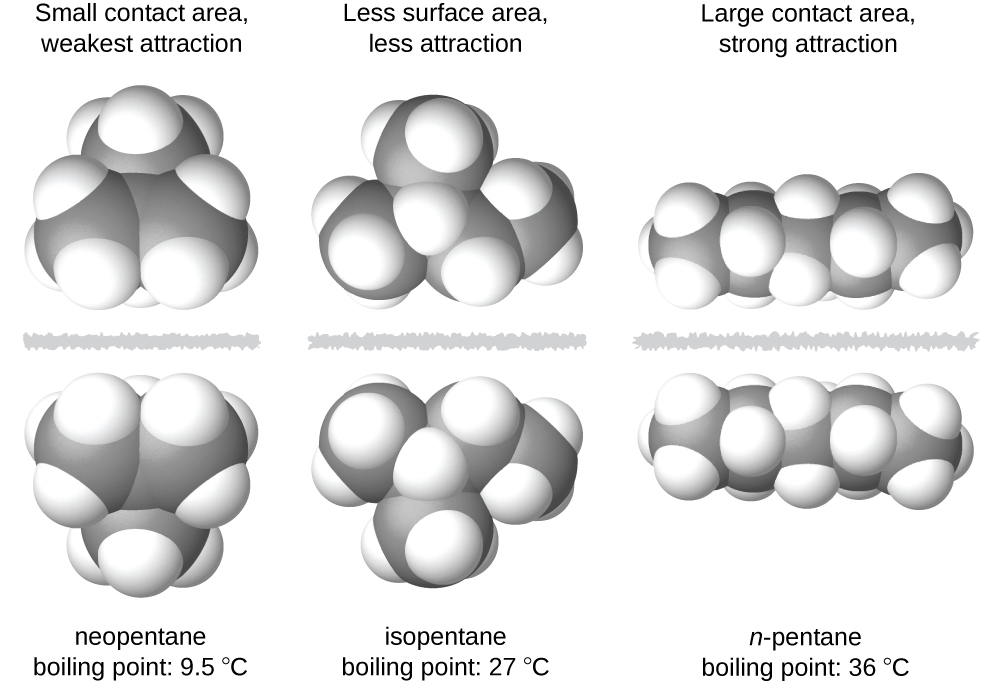

The shapes of molecules also affect the magnitudes of the dispersion forces between them. For example, boiling points for the isomers n-pentane, isopentane, and neopentane (shown in Figure 2.1.6) are 36 °C, 27 °C, and 9.5 °C, respectively. Even though these compounds are composed of molecules with the same chemical formula, C5H12, the difference in boiling points suggests that dispersion forces in the liquid phase are different, being greatest for n-pentane and least for neopentane. The elongated shape of n-pentane provides a greater surface area available for contact between molecules, resulting in correspondingly stronger dispersion forces. The more compact shape of isopentane offers a smaller surface area available for intermolecular contact and, therefore, weaker dispersion forces. Neopentane molecules are the most compact of the three, offering the least available surface area for intermolecular contact and, hence, the weakest dispersion forces. This behavior is analogous to the connections that may be formed between strips of VELCRO brand fasteners: the greater the area of the strip’s contact, the stronger the connection.

Figure 2.1.6. The strength of the dispersion forces increases with the contact area between molecules, as demonstrated by the boiling points of these pentane isomers.

Geckos and Intermolecular Forces

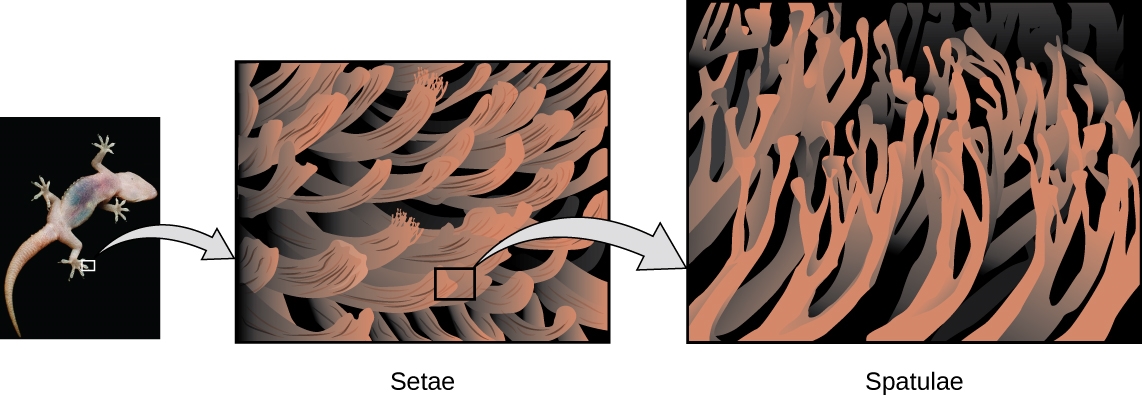

Geckos have an amazing ability to adhere to most surfaces. They can quickly run up smooth walls and across ceilings that have no toe-holds, and they do this without having suction cups or a sticky substance on their toes. And while a gecko can lift its feet easily as it walks along a surface, if you attempt to pick it up, it sticks to the surface. How are geckos (as well as spiders and some other insects) able to do this? Although this phenomenon has been investigated for hundreds of years, scientists only recently uncovered the details of the process that allows geckos’ feet to behave this way.

Geckos’ toes are covered with hundreds of thousands of tiny hairs known as setae, with each seta, in turn, branching into hundreds of tiny, flat, triangular tips called spatulae. The huge numbers of spatulae on its setae provide a gecko (shown in Figure 2.1.7) with a large total surface area for sticking to a surface. In 2000, Kellar Autumn, who leads a multi-institutional gecko research team, found that geckos adhered equally well to both polar silicon dioxide and nonpolar gallium arsenide. This proved that geckos stick to surfaces because of dispersion forces—weak intermolecular attractions arising from temporary, synchronized charge distributions between adjacent molecules. Although dispersion forces are very weak, the total attraction over millions of spatulae is large enough to support many times the gecko’s weight.

In 2014, two scientists developed a model to explain how geckos can rapidly transition from “sticky” to “non-sticky.” Alex Greaney and Congcong Hu at Oregon State University described how geckos can achieve this by changing the angle between their spatulae and the surface. Geckos’ feet, which are normally non sticky, become sticky when a small shear force is applied. By curling and uncurling their toes, geckos can alternate between sticking and unsticking from a surface, and thus easily move across it. Further investigations may eventually lead to the development of better adhesives and other applications.

Figure 2.1.7. Geckos’ toes contain large numbers of tiny hairs (setae), which branch into many triangular tips (spatulae). Geckos adhere to surfaces because of van der Waals attractions between the surface and a gecko’s millions of spatulae. By changing how the spatulae contact the surface, geckos can turn their stickiness “on” and “off.” (credit photo: modification of work by “JC*+A!”/Flickr)

Dipole-Dipole Attractions

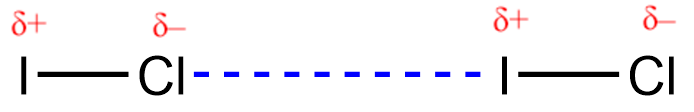

You may recall from your high school chemistry class on chemical bonding and molecular geometry that polar molecules have a partial positive charge on one side and a partial negative charge on the other side of the molecule — a separation of charge called a dipole. Consider a polar molecule such as hydrogen chloride, HCl. In the HCl molecule, the more electronegative Cl atom bears the partial negative charge, whereas the less electronegative H atom bears the partial positive charge. An attractive force between HCl molecules results from the attraction between the positive end of one HCl molecule and the negative end of another. This attractive force is called a dipole-dipole attraction—the electrostatic force between the partially positive end of one polar molecule and the partially negative end of another, as illustrated in Figure 2.1.8.

Figure 2.1.8. This image shows two arrangements of polar molecules, such as HCl, that allow an attraction between the partial negative end of one molecule and the partial positive end of another.

The effect of a dipole-dipole attraction is apparent when we compare the properties of HCl molecules to nonpolar F2 molecules. Both HCl and F2 consist of the same number of atoms and have approximately the same molecular mass. At a temperature of 150 K, molecules of both substances would have the same average Ek. However, the dipole-dipole attractions between HCl molecules are sufficient to cause them to condense to form a liquid, whereas the relatively weaker dispersion forces between nonpolar F2 molecules are not, and so this substance is gaseous at this temperature. The higher normal boiling point of HCl (188 K) compared to F2 (85 K) is a reflection of the greater strength of dipole-dipole attractions between HCl molecules, compared to the attractions between nonpolar F2 molecules. We will often use values such as boiling or freezing points, or enthalpies of vaporization or fusion, as indicators of the relative strengths of IMFs of attraction present within different substances.

Example 2.1.2 – Dipole-Dipole Forces and Their Effects

Predict which will have the higher boiling point: N2 or CO. Explain your reasoning.

Solution

CO and N2 are both diatomic molecules with masses of about 28 amu, so they experience similar London dispersion forces. Because CO is a polar molecule, it experiences dipole-dipole attractions. Because N2 is nonpolar, its molecules cannot exhibit dipole-dipole attractions. The dipole-dipole attractions between CO molecules are comparably stronger than the dispersion forces between nonpolar N2 molecules, so CO is expected to have the higher boiling point.

Check Your Learning 2.1.2 – Dipole-Dipole Forces and Their Effects

Predict which will have the higher boiling point: iodine chloride (ICl) or molecular bromine (Br2). Explain your

reasoning.

Answer

ICl. ICl and Br2 have similar masses (~160 amu) and therefore experience similar London dispersion forces. ICl is polar and thus also exhibits dipole-dipole attractions; Br2 is nonpolar and does not. The relatively stronger dipole-dipole attractions require more energy to overcome, so ICl will have the higher boiling point.

Hydrogen Bonding

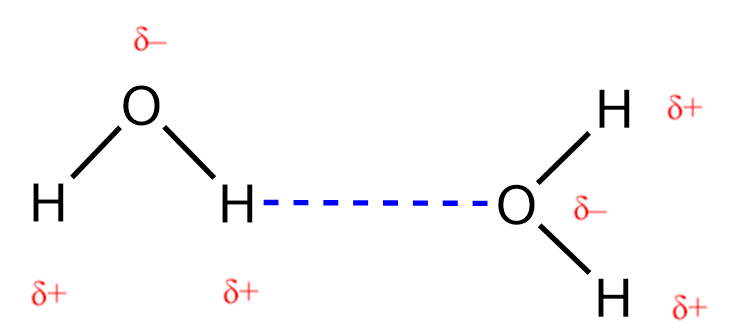

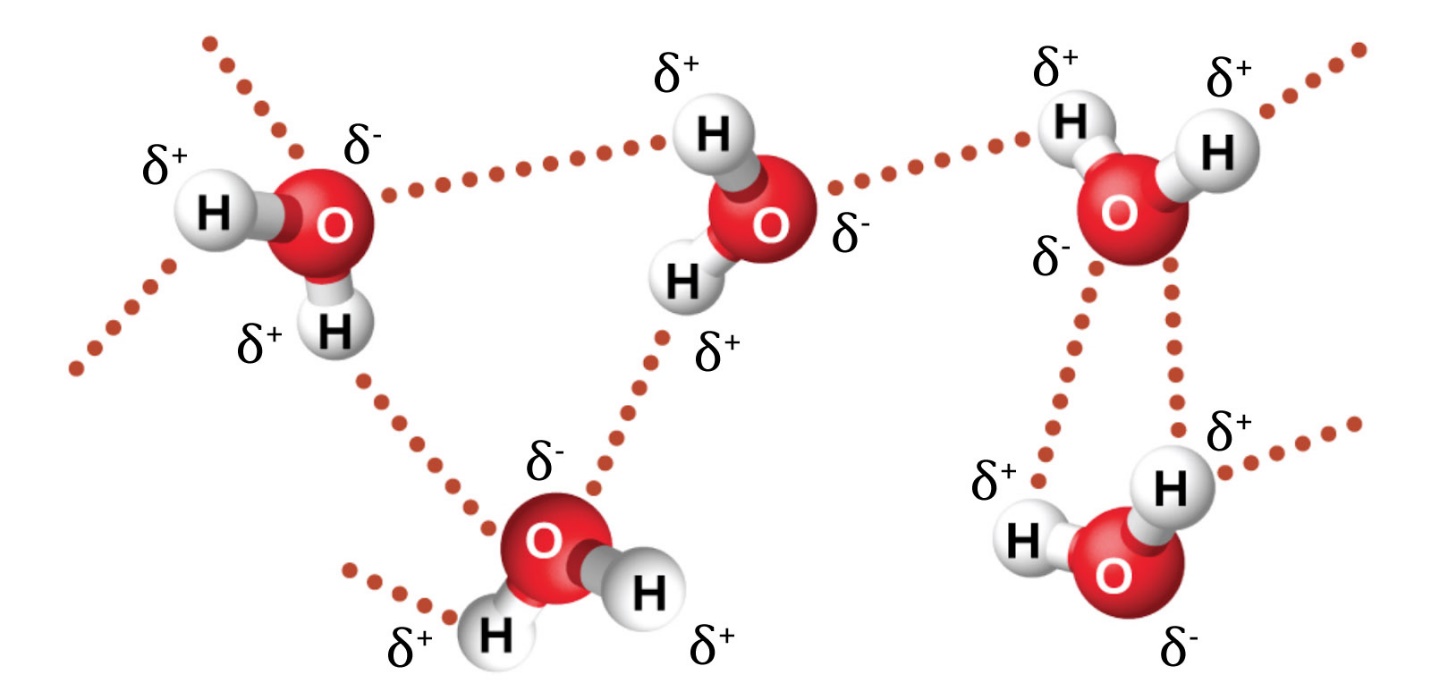

Nitrosyl fluoride (ONF, molecular mass 49 amu) is a gas at room temperature. Water (H2O, molecular mass 18 amu) is a liquid, even though it has a lower molecular mass. We clearly cannot attribute this difference between the two compounds to dispersion forces. Both molecules have about the same shape and ONF is the heavier and larger molecule. It is, therefore, expected to experience more significant dispersion forces. Additionally, we cannot attribute this difference in boiling points to differences in the dipole moments of the molecules. Both molecules are polar and exhibit comparable dipole moments. The large difference between the boiling points is due to a particularly strong dipole-dipole attraction that may occur when a molecule contains a hydrogen atom bonded to a fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen atom. These three elements have very high values of electronegativity, the ability of an atom to attract electron density in a chemical bond towards its own nucleus (defined and discussed in Section 9.3). The very large difference in electronegativity between the H atom (2.1) and the atom to which it is bonded (4.0 for a F atom, 3.5 for an O atom, or 3.0 for a N atom), combined with the very small size of a H atom and the relatively small sizes of F, O, or N atoms, leads to highly concentrated partial charges with these atoms. Molecules with F-H, O-H, or N-H moieties are very strongly attracted to similar moieties in nearby molecules, a particularly strong type of dipole-dipole attraction called hydrogen bonding. Examples of hydrogen bonds include HF⋯HF, H2O⋯HOH, and H3N⋯HNH2, in which the hydrogen bonds are denoted by dots. Figure 2.1.9 illustrates hydrogen bonding between water molecules.

Figure 2.1.9. Water molecules participate in multiple hydrogen-bonding interactions with nearby water molecules.

Despite use of the word “bond,” keep in mind that hydrogen bonds are intermolecular attractive forces, not intramolecular attractive forces (covalent bonds). Hydrogen bonds are much weaker than covalent bonds, only about 5 to 10% as strong, but are generally much stronger than other dipole-dipole attractions and dispersion forces.

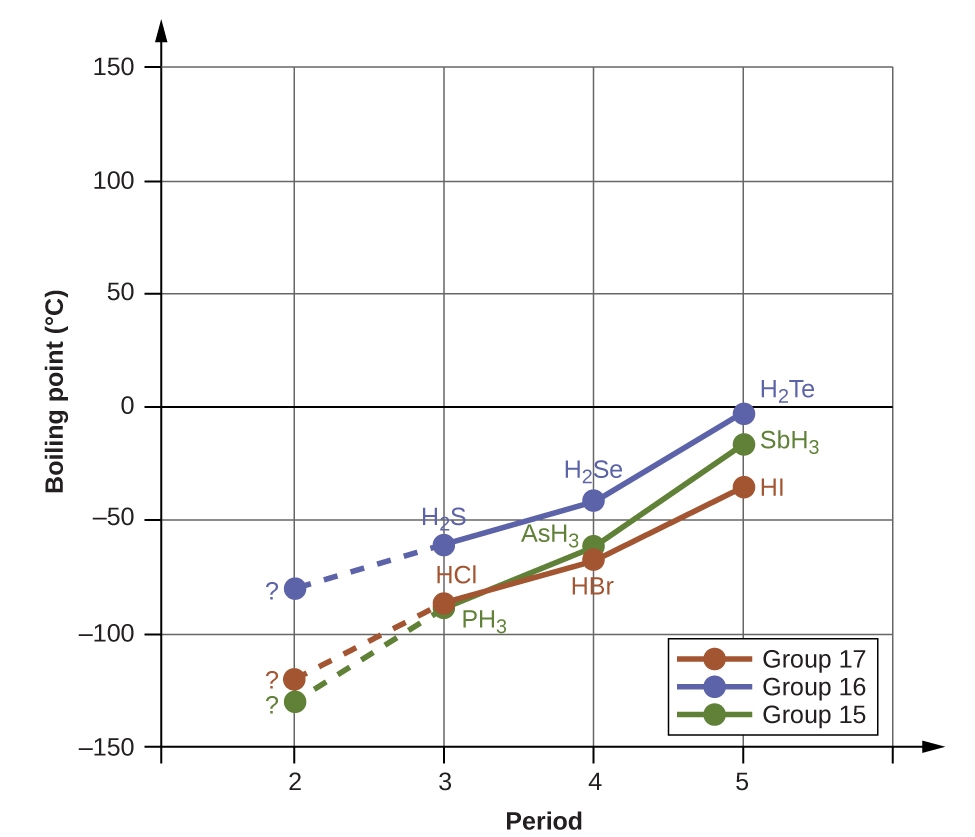

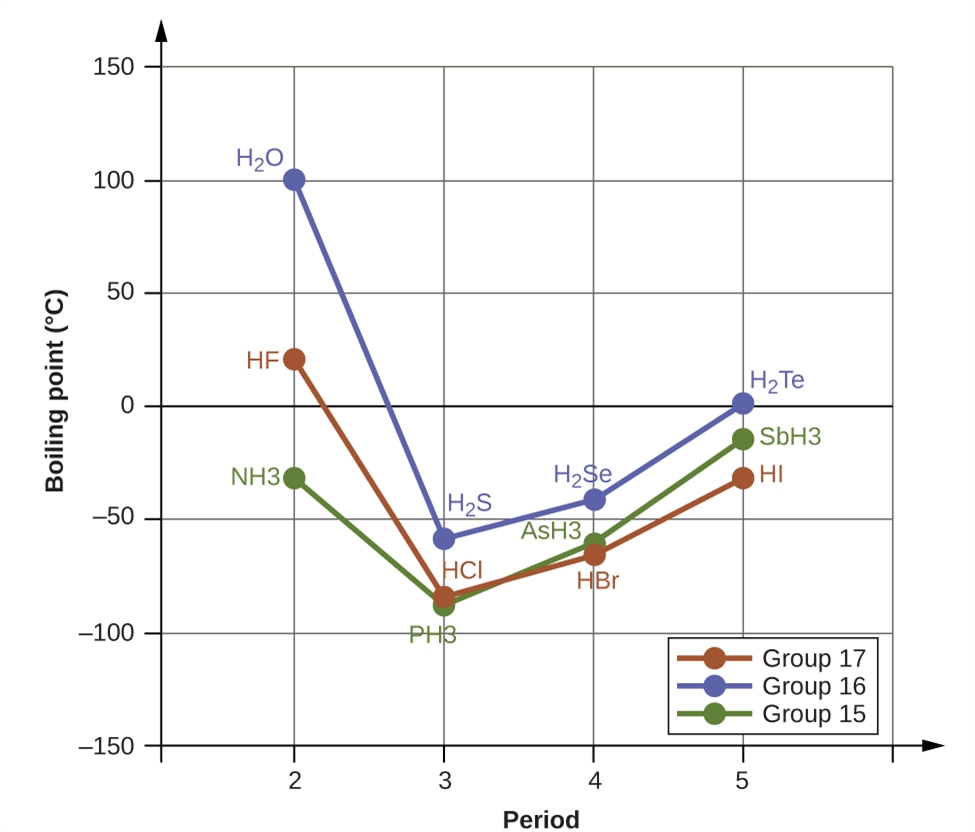

Hydrogen bonds have a pronounced effect on the properties of condensed phases (liquids and solids). For example, consider the trends in boiling points for the binary hydrides of group 15 (NH3, PH3, AsH3, and SbH3), group 16 hydrides (H2O, H2S, H2Se, and H2Te), and group 17 hydrides (HF, HCl, HBr, and HI). The boiling points of the heaviest three hydrides for each group are plotted in Figure 2.1.10. As we progress down any of these groups, the polarities of the molecules decrease slightly, whereas the sizes of the molecules increase substantially. The effect of increasingly stronger dispersion forces dominates that of increasingly weaker dipole-dipole attractions, and the boiling points are observed to increase steadily.

Figure 2.1.10. For the group 15, 16, and 17 hydrides, the boiling points for each class of compounds increase with increasing molecular mass for elements in periods 3, 4, and 5.

If we use this trend to predict the boiling points for the lightest hydride for each group, we would expect NH3 to boil at about −120 °C, H2O to boil at about −80 °C, and HF to boil at about −110 °C. However, when we measure the boiling points for these compounds, we find that they are dramatically higher than the trends would predict, as shown in Figure 2.1.11. The stark contrast between our naïve predictions and reality provides compelling evidence for the strength of hydrogen bonding.

Figure 2.1.11. In comparison to periods 3−5, the binary hydrides of period 2 elements in groups 17, 16 and 15 (F, O and N, respectively) exhibit anomalously high boiling points due to hydrogen bonding.

Example 2.1.3 – Effect of Hydrogen Bonding on Boiling Points

Consider the compounds dimethylether (CH3OCH3), ethanol (CH3CH2OH), and propane (CH3CH2CH3). Their boiling points, not necessarily in order, are −42.1 °C, −24.8 °C, and 78.4 °C. Match each compound with its boiling point. Explain your reasoning.

Solution

The VSEPR-predicted shapes of CH3OCH3, CH3CH2OH, and CH3CH2CH3 are similar, as are their molar masses (46 g/mol, 46 g/mol, and 44 g/mol, respectively), so they will exhibit similar dispersion forces. Since CH3CH2CH3 is nonpolar, it may exhibit only dispersion forces. Because CH3OCH3 is polar, it will also experience dipole-dipole attractions. Finally, CH3CH2OH has an −OH group, and so it will experience the uniquely strong dipole-dipole attraction known as hydrogen bonding. So the ordering in terms of strength of IMFs, and thus boiling points, is CH3CH2CH3 < CH3OCH3 < CH3CH2OH. The boiling point of propane is −42.1 °C, the boiling point of dimethylether is −24.8 °C, and the boiling point of ethanol is 78.5 °C.

Check Your Learning 2.1.3 – Effect of Hydrogen Bonding on Boiling Points

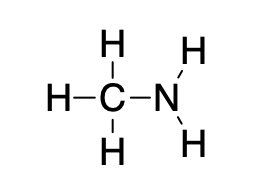

Ethane (CH3CH3) has a melting point of −183 °C and a boiling point of −89 °C.

Predict the relative melting and boiling points for methylamine (CH3NH2). Explain your reasoning.

Answer

CH3CH3 and CH3NH2 are similar in size and mass, but methylamine possesses two N–H bonds and therefore will exhibit hydrogen bonding. This greatly increases its IMFs, and therefore its melting and boiling points. Therefore, the melting point and boiling point for methylamine are predicted to be significantly greater than those of ethane. Our prediction is confirmed by literature values: CH3NH2 has a melting point of −93 °C and a boiling point of −6 °C.

Hydrogen Bonding and DNA

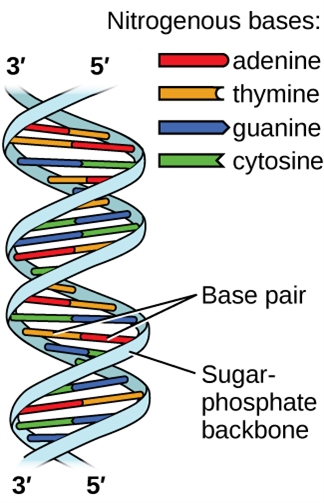

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) is found in every living organism and contains the genetic information that determines the organism’s characteristics, provides the blueprint for making the proteins necessary for life, and serves as a template to pass this information on to the organism’s offspring. A DNA molecule consists of two (anti-) parallel chains of repeating nucleotides, which form its well-known double-helical structure, as shown in Figure 2.1.12.

Figure 2.1.12. Two separate DNA molecules form a double-stranded helix in which the molecules are held together via hydrogen bonding. (credit: modification of work by Jerome Walker, Dennis Myts)

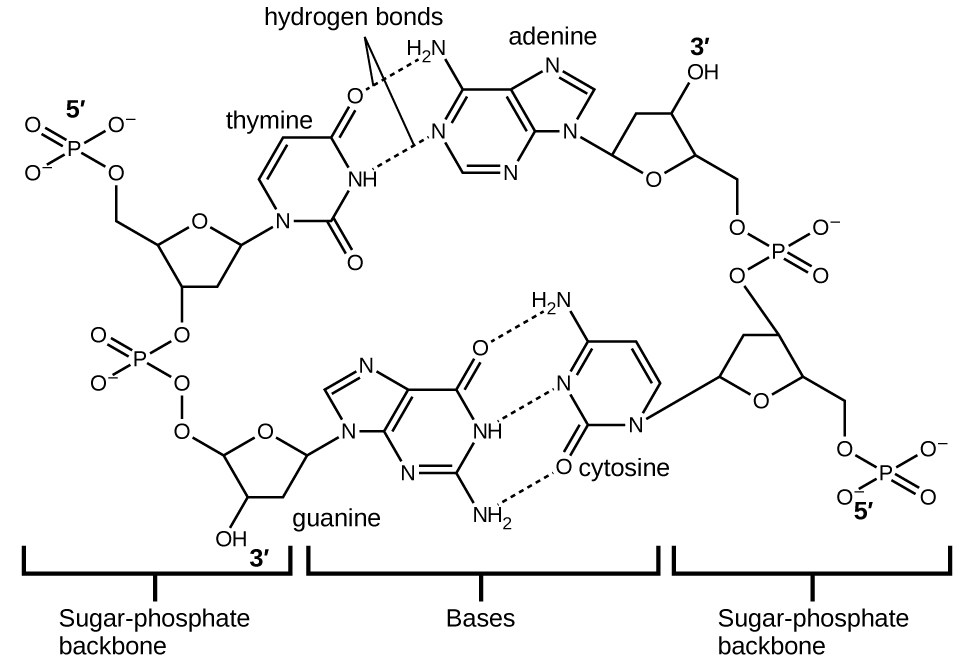

Each nucleotide contains a (deoxyribose) sugar bound to a phosphate group on one side, and one of four nitrogenous bases on the other. Two of the bases, cytosine (C) and thymine (T), are single-ringed structures known as pyrimidines. The other two, adenine (A) and guanine (G), are double-ringed structures called purines. These bases form complementary base pairs consisting of one purine and one pyrimidine, with adenine pairing with thymine, and cytosine with guanine. Each base pair is held together by hydrogen bonding. A and T share two hydrogen bonds, C and G share three, and both pairings have a similar shape and structure Figure 2.1.13.

Figure 2.1.13. The geometries of the base molecules result in maximum hydrogen bonding between adenine and thymine (AT) and between guanine and cytosine (GC), so-called “complementary base pairs.”

The cumulative effect of millions of hydrogen bonds effectively holds the two strands of DNA together. Importantly, the two strands of DNA can relatively easily “unzip” down the middle since hydrogen bonds are relatively weak compared to the covalent bonds that hold the atoms of the individual DNA molecules together. This allows both strands to function as a template for replication.

Summary

Transitions between the solid and liquid or the liquid and gas phases are due to changes in intermolecular interactions but do not affect intramolecular interactions. The three major types of intermolecular interactions are dipole–dipole interactions, London dispersion forces (these two are often referred to collectively as van der Waals forces), and hydrogen bonds. Dipole–dipole interactions arise from the electrostatic interactions of the positive and negative ends of molecules with permanent dipole moments; their strength is proportional to the magnitude of the dipole moment and to 1/r6, where r is the distance between dipoles. London dispersion forces are due to the formation of instantaneous dipole moments in polar or nonpolar molecules as a result of short-lived fluctuations of electron charge distribution, which in turn cause the temporary formation of an induced dipole in adjacent molecules. Like dipole–dipole interactions, their energy falls off as 1/r6. Larger atoms tend to be more polarizable than smaller ones because their outer electrons are less tightly bound and are therefore more easily perturbed. Hydrogen bonds are especially strong dipole–dipole interactions between molecules that have hydrogen bonded to a highly electronegative atom, such as O, N, or F. The resulting partially positively charged H atom on one molecule (the hydrogen bond donor) can interact strongly with a lone pair of electrons of a partially negatively charged O, N, or F atom on adjacent molecules (the hydrogen bond acceptor). Because of strong hydrogen bonding between water molecules, water has an unusually high boiling point, and ice has an open, cage-like structure that is less dense than liquid water. Table 2.1.2 summarizes relative bond energies of intermolecular forces.

Table 2.1.2 Relative Bond Energies of Intermolecular Forces

|

Intermolecular Force |

Diagram |

Energy (kJ/mol)† |

|

London dispersion |

|

Under 4 – 63 |

|

Dipole-dipole |

|

2 – 8 |

|

Hydrogen bonds |

|

4 – 50 |

| †Ege, Seyhan (2003) Organic Chemistry: Structure and Reactivity. Houghton Mifflin College. ISBN 0618318097. pp. 30–33, 67. | ||

Questions

★ Questions

1. Open the PhET States of Matter Simulation to answer the following questions:

(a) Select the Solid, Liquid, Gas tab. Explore by selecting different substances, heating and cooling the systems, and changing the state. What similarities do you notice between the four substances for each phase (solid, liquid, gas)? What differences do you notice?

(b) For each substance, select each of the states and record the given temperatures. How do the given temperatures for each state correlate with the strengths of their intermolecular attractions? Explain.

(c) Select the Interaction Potential tab, and use the default neon atoms. Move the Ne atom on the right and observe how the potential energy changes. Select the Total Force button, and move the Ne atom as before. When is the total force on each atom attractive and large enough to matter? Then select the Component Forces button, and move the Ne atom. When do the attractive (van der Waals) and repulsive (electron overlap) forces balance? How does this relate to the potential energy versus the distance between atoms graph? Explain.

2. Define the following and give an example of each:

(a) Dispersion force

(b) Dipole-dipole attraction

(c) Hydrogen bond

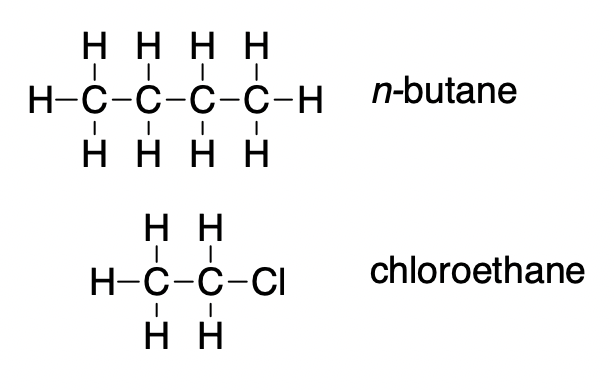

3. On the basis of intermolecular attractions, explain the differences in the boiling points of n–butane (−1 °C) and chloroethane (12 °C), which have similar molar masses.

4. The melting point of H2O (s) is 0 °C. Would you expect the melting point of H2S (s) to be −85 °C, 0 °C, or 185 °C? Explain your answer.

5. Silane (SiH4), phosphine (PH3), and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) melt at −185 °C, −133 °C, and −85 °C, respectively. What does this suggest about the polar character and intermolecular attractions of the three compounds?

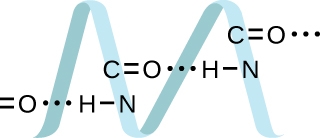

6. Proteins are chains of amino acids that can form in a variety of arrangements, one of which is a helix. What kind of IMF is responsible for holding the protein strand in this shape? On the protein image, show the locations of the IMFs that hold the protein together:

7. Identify the intermolecular forces present in the following solids:

(a) CH3CH2OH

(b) CH3CH2CH3

(c) CH3CH2Cl

Answers

1. (a) Similarities: Solid and liquid are more dense compared to gas. The higher temperature the system has, the faster the molecular move. Differences: For water, the liquid state is denser than solid state; while other solids are denser than their liquid state. Different substances have different temperatures.

| Temperature | Neon | Argon | Oxygen | Water |

| Solid | -260 °C | -230 °C | -242 °C | -116 °C |

| Liquid | -247 °C | -187 °C | -204 °C | 55 °C |

| Gas | -218 °C | -84 °C | -79 °C | 536 °C |

The higher temperature they have, the stronger IMF the substances have.

(b) The potential energy first decreases in the negative region, and then keeps increasing. When the distance between two atoms is greater than ε, the total force on each atom is attractive and large enough to matter. When the distance between two atoms is ε, the attractive (van der Waals) and repulsive (electron overlap) forces balance. At this point, the whole system has the lowest potential energy.

2. (a) Dispersion forces occur as an atom develops a temporary dipole moment when its electrons are distributed asymmetrically about the nucleus. This structure is more prevalent in large atoms such as argon or radon. A second atom can then be distorted by the appearance of the dipole in the first atom. The electrons of the second atom are attracted toward the positive end of the first atom, which sets up a dipole in the second atom. The net result is rapidly fluctuating, temporary dipoles that attract one another (example: Ar).

(b) A dipole-dipole attraction is a force that results from an electrostatic attraction of the positive end of one polar molecule for the negative end of another polar molecule (example: ICI molecules attract one another by dipole-dipole interaction).

(c) Hydrogen bonds form whenever a hydrogen atom is bonded to one of the more electronegative atoms, such as a fluorine, oxygen, or nitrogen atom. The electrostatic attraction between the partially positive hydrogen atom in one molecule and the partially negative atom in another molecule gives rise to a strong dipole-dipole interaction called a hydrogen bond (example: HF⋯HF).

3. Only rather small dipole-dipole interactions from C-H bonds are available to hold n-butane in the liquid state. Chloroethane, however, has rather large dipole interactions because of the Cl-C bond; the interaction is therefore stronger, leading to a higher boiling point.

4. −85 °C. Water has stronger hydrogen bonds so it melts at a higher temperature.

5. The higher the melting point reflects stronger intermolecular forces. In this case, silane has the strongest intermolecular forces whereas sulfide has the weakest. Although, the polarity cannot be directly determined based on the melting points.

6. H-bonding is the principle IMF holding the DNA strands together. The H-bonding is between the N−H and C=O.

7.

(a) Hydrogen bonding and dispersion forces

(b) Dispersion forces

(c) Dipole-dipole attraction and dispersion forces

Non-covalent attractive force between atoms, molecules, and/or ions

273.15 K (0 °C) and 1 bar (100 kPa)

Attractive or repulsive force between molecules, including dipole-dipole, dipole-induced dipole, and London dispersion forces; does not include forces due to covalent or ionic bonding, or the attraction between ions and molecules

Intermolecular force caused by molecules with a permanent dipole

Temporary dipole that occurs for a brief moment in time when the electrons of an atom or molecule are distributed asymmetrically

Temporary dipole formed when the electrons of an atom or molecule are distorted by the instantaneous dipole of a neighboring atom or molecule

Measure of the ability of a charge to distort a molecule’s charge distribution (electron cloud)

Intermolecular force caused by molecules with a permanent dipole

Intermolecular force that occurs when exceptionally strong dipoles attract; these interactions exist when hydrogen is bonded to one of the three most electronegative elements: F, O, or N