Emergency and Disaster Response

When you, as a nursing leader, are faced with a response to an emergency or disaster, you will likely be able to rely on several scenarios for which plans have been developed such as for fire, flood, power loss, evacuations and so on. However, it is also likely that a disaster will not unfold in a way that allows the plan to be followed exactly. For example, when the twin towers were attacked in New York, the emergency plan called for the Emergency Operations Command Centre to be in one of the World Trade Centre towers on the 23rd floor. As the disaster unfolded, this plan needed to be changed.

The major value of the response plans and preparedness is that a number of scenarios have been developed and worked through logically. You can anticipate that the plan will not be totally suitable and applicable to the situation you are facing but it will have elements that will be very applicable. When pieces of the plan need to be added, deleted, or changed, this can be done more quickly and effectively when the pieces can be used like a jigsaw puzzle to adapt to the situation that presents itself. The plan will need to be adapted and modified according to the situation. This is where the command structures become critical. This will be discussed in the next section.

Incident Management as Emergency and Disaster Response

The response to any widespread emergency or disaster requires significant coordination and communication. In most preparedness plans, the response will be managed through a central and relatively standardized command centre structure. There is typically a single commander who coordinates information and directs priorities and actions through “section chiefs” at a central location usually referred to as the Emergency Operations Centre (EOC). The EOC is a gathering location and communications hub. The leaders who gather at the EOC, follow a standardized communication and responsibility structure that has been practiced in drills and exercises. The general outline followed by most organizations can be found in the Emergency Management Ontario information. Overall, these response structures and processes are elements of an Incident Management System (IMS).

The core principles of an incident management system (IMS) are:

- Communication

- Coordination

- Collaboration

- Flexibility

IMS helps incident responders work together to achieve common objectives. By using IMS, responders can adapt to the specific needs of an incident using common roles, responsibilities, and structures. The standardization supports interoperability and coordination. Ontario’s IMS is interoperable and closely aligned with other incident management systems around the world, including NIMS 3.0 (National Incident Management System in the United States). At the site, Ontario’s IMS can be fully interoperable with the Incident Command System (ICS) used by other communities and organizations in Ontario.

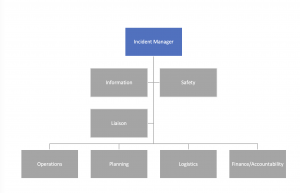

All these systems share a common approach to divide the incident response effort. Similar tasks grouped together are known as “functions” or sections, each with a chief. Each chief has a group (ideally 7 or fewer personnel) to take the actions required by the plan. The sections and the corresponding chiefs and functions may need to be adapted to fit the circumstances or human resources. But the standard outline is a strong place to start.

IMS functions common to all incidents are listed below followed by a brief description:

- Coordination and Command,

- Operations,

- Planning,

- Logistics,

- Finance and Administration, and

- Public Information Management.

1. Operations Section: The role of the Operations Section is to meet current incident objectives and priorities stated on behalf of Coordination and Command and in the Incident Action Plan (IAP). The Operations Section:

- At the site:Organizes, coordinates and supervises the tactical elements of an incident such as personnel or equipment

- In an EOC:Takes on the tactical responsibilities and involves activities such as coordinating communications and providing situational awareness to and from the site.

2. Planning Section: Collects, confirms, analyzes and shares incident information gathered from incident responders. Internal communication is a key activity within the Planning Section. The Planning Section also prepares the IAP and develops contingency and long-term plans.

- Situational Awareness:Maintaining and sharing situational awareness is often the responsibility of the Situation Unit within the Planning Section. In some EOCs, situational awareness can be a section of its own or under the Operations Section. Maintaining situational awareness is a key function across any incident response. It is important to clearly identify which section is responsible for situational awareness within the incident response structure.

3. Logistics Section: Arranges and provides services and supports including personnel, supplies, facilities and other resources to an incident. For example, the Logistics Section may arrange transportation or source equipment such as pumps and sandbags.

4. Finance and Administration Section: Manages incident-specific finance and administration activities including payroll, vendor contracts and incident cost tracking.

5. Public Information Management Section: Develops and shares messages directly to the public and through the media. Tracks media reports including social media feeds and shares information with Coordination and Command. Incident responders under this section should connect directly with the community if required.

Other Sections that May (depending on the situation) Need to be Added Include:

Emergency Social Services (ESS): Is responsible for providing social services to individuals and families affected by emergencies or disasters to preserve their well-being. The ESS function aims to assist individuals meet their basic human needs. They may provide food, clothing, shelter, personal services, registration and inquiry services. These services are provided on a short-term, temporary basis where individuals and families affected by an incident can receive physical, mental, social and economic support.

Scientific/Technical: Performs ongoing monitoring and surveillance of scientific or technical issues including field-based monitoring, sampling and surveillance. This function also analyzes and evaluates scientific data to provide expert technical advice to leadership and makes recommendations for protective action, mitigation and remediation.

Continuity of Operations: Ensures that the day-to-day operations within a community or organization are maintained. In certain incidents, there may be a need to closely coordinate these efforts with the overall response.

In the healthcare context, Ontario hospitals have a designated CODE ORANGE plan to respond to emergencies with mass casualties, such as the train derailment (example: Lac Megantic 2013 but more on this disaster later). In such a scenario there would be an EOC for the municipal services (fire, police) and another EOC at the hospital itself. The communication and coordination across these two EOC command structures is essential and needs to be practiced as part of preparedness training exercises for both the hospital and the municipality services. One of the section chiefs would be assigned to this liaison role. The following image is the Command Structure suggested in the OHA toolkit and indicates a specific Liaison Section chief. This role is designed to be in very close contact with the community partners of Emergency Services (ambulance, fire, police) and their EOC tables and structures.

Activity #1

View this video to see a preparedness exercise of an Emergency Operations Centre for an earthquake response on a large university campus. It is not specific to healthcare, but it is a good overview and simulates a large scale response EOC.

Video: University of California, Berkeley’s Emergency Operations Center (EOC) (7:35)

Activity #2

View this video from the US Centre for Disease Control for a good explanatory approach using disease outbreak as examples.

Video: Emergency Operations Center (EOC) 101 (6:00)

In very large-scale events, there may need to be multiple command centre operations. For example, in the Ontario COVID pandemic response there was a Critical Care Command Centre of operations to coordinate critical care capacity and pandemic response across the province.

The Command Centre enabled one single provincial decision-making body to:

- Monitor critical care capacity needs in real time

- Respond promptly to predicted and unpredicted surges in demand at a provincial level

- Facilitate movement of COVID-19 patients, equipment, and supplies across regional boundaries based on need by liaising with Regional Hubs

- Make final decisions on provincial critical care issues

For more information on this Command Centre and other Ontario Pandemic responses, see the following link – COVID-19 Health System Response Materials.

Another resource that may interest you regarding specific aspects of the critical care COVID response can be viewed through Ontario Critical Care Clinical Practice Rounds (OC3PR). The “OC3PR” resource was established by clinicians to share emerging information related to the COVID response in critical care settings. The site includes excellent webinars (each about 60 min).

Two that may be of particular interest to the nursing leader perspective include:

1. Expanded team-based models

-

- Recommendations on how to organize health human resources (HHR) in times of extreme shortage or mismatch of supply and demand of HHR.

- Video: Implementing Team Based Models during COVID-19: Tips and Lessons Learned (55:40)

2. Emergency standard of care

-

- Video: Maximizing Care through an Emergency Standard of Care (1:34:39)

Mass Casualty Triage in Disaster Response

For mass casualty events, one of the challenges facing first responders and nurses at the site, as well as at the local hospital emergency department, is that of triage for a large number of people. There are standard practices in place that provide guidance and can be practiced in preparedness exercises.

The approach is based on the ethical premise that the best course of action in a mass casualty event is to save the most possible lives. The individual triage decision may require that only comfort (palliation) care be provided to casualties that have a very low probability of surviving their injuries and would require the use of major or extraordinary resources for a low probability of survival. Such a decision is typically not required of health professionals in affluent countries like Canada so the moral distress can be significant. Therefore, it is only appropriate in the context of mass casualty event where casualties far exceed resources.

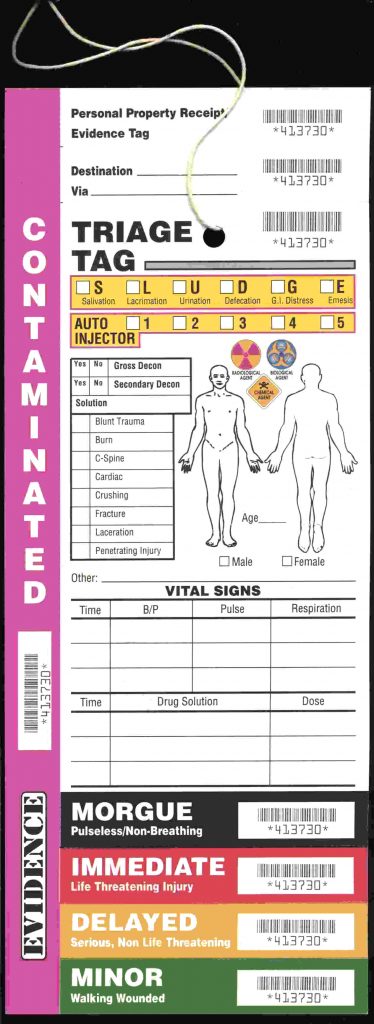

In general, Triage separates/sorts the injured into groups for different urgency and action:

- Those injured who can be helped by immediate transportation or treatment – Red

- Those injured whose transport or treatment can be delayed – Yellow

- Those with minor injuries, who need help less urgently – Green

When the triage is completed, typically at the incident site, the key information (and associated triage colour code) is entered onto a standardized tag to communicate effectively to other rescue team members.

Activity #3

The following video introduces the START method of mass casualty triage and aims to make it easy to learn and remember.

Video: Disaster Triage Nursing (Color Tag System & START Method) for Mass Casualty (10:37)

The following slide deck is a good introduction if you prefer point form material. It is a very long deck at 95 slides but has 50 ‘practice slides’ which you will likely find very helpful in learning the START method.

This deck notes 4 different types of triage:

- MASS (Move, Assess, Sort, Send) – this may be used at the disaster scenes when transport can be organized.

- ESI – Emergency Severity Index

- SALT – Sort, Assess, Life Saving interventions, Treatment

- START – Simple Triage and Rapid Treatment (JumpSTART for children age 0-8)

This deck also references a mass casualty event due to a bombing at a Bali nightclub in 2002. It includes a quote:

”As bad as the scene was 20 minutes after the blast, it only got worse. Patients who could self-evacuate generally had relatively minor injuries. They arrived on foot, by taxi and by motorcycle, and they were treated as they came in.” “But then the ambulances started to arrive with the most serious patients—the burn victims…” “By then, though, the operating rooms were completely full. They had to wait”

This cautionary tale paints the picture of the need to balance resources available with the casualties. It also highlights the need for communication and coordination to estimate impacts when possible.

if you prefer a more academic presentation you may wish to watch the following video.

Video: START Triage Basics (7:21)

During the COVID pandemic, there were a number of ethically challenging conversations on preparedness for the potential scenario that patients needing ventilator care would exceed available resources – in a mass casualty event of a different sort. As the world watched pressures of exponential increases in ICU admissions unfold in Lombardi, Italy, other jurisdictions began to think this through in their emergency planning. One reported triage criterion was age. This was unacceptably arbitrary for many opinions because it did not consider survivability directly (age may not be the best proxy for potential for survival). This led to significant consultation, and debate about whether, and how, to triage in the face of overwhelming needs. Other key perspectives were that clear triage guidelines would reduce the moral distress burden on physicians, and it be more ethically principled to have a standard and agreed upon framework for triage, if it became necessary. If such a framework were not in place, choices would be at the discretion and interpretation and biases of many different individuals. As the framework under discussion evolved, it became a document of careful consideration of clinical probabilities for potential outcomes and treatments. It became less like ‘triage’, which connotes a rapid and limited assessment, but more of a ‘standard of care’ in the context of an emergency.

Activity #4

Fortunately, Ontario did not need to adopt this emergency standard of care, thanks to other measures of mitigation and preparedness, (as of August 2021). However, I would highly recommend exploration of this topic as an ethical and logistical consideration of responding to a significant emergency mismatch or resources and need.

Reflection Exercise