Introduction to Imperfect Competition

Monopolizing on History

Many of the case studies in this text have focused on current events, but lets step into the past to observe how monopoly, or near monopolies, have helped shape history. In the spring of 1773, the East India Company, a firm that, in its time, was designated “too big to fail,” was experiencing ongoing financial difficulties. To help shore up the failing firm, the British Parliament authorized the Tea Act. The act continued the tax on teas and made the East India Company the sole legal supplier of tea to the American colonies, giving them legal monopoly power. By November, the citizens of Boston had had enough. They refused to permit the tea to be unloaded, citing their main complaint: “No taxation without representation.” Arriving tea-bearing ships were warned via several newspapers, including The Massachusetts Gazette, “We are prepared, and shall not fail to pay them an unwelcome visit.”

The result? When the ships arrived, a group called the Sons of Liberty boarded them and threw their chests of tea into the sea. This was the culmination of a resistance movement throughout British America against the Tea Act. Ultimately this escalated to the American Revolutionary War in 1775.

Fast forward in time to 1860—the eve of the American Civil War—to another near-monopoly supplier of historical significance: the U.S. cotton industry. At the time, the Southern States provided the majority of the cotton Britain imported. Wanting to secede from the Union, the South hoped to leverage Britain’s high dependency on its cotton into formal diplomatic recognition of the Confederate States of America.

Southern cotton-merchants spontaneously refused to ship out their cotton in early 1861. The strategy, now known as ‘King Cotton’ was relatively unsuccessful. By summer 1861, the Union Navy had blockaded every major Confederate port and shut down over 95% of exports, making it so they couldn’t export Cotton if they wanted to. Britain was able to draw on stockpiles of cotton while finding imports from new sources, and the confederacy no longer received much needed gold.

Monopoly sellers often see no threats to their superior marketplace position. In the case of tea, the monopoly market structure was a key reason for social change. With Cotton, its power a military strategy. In this topic we will explore a range of market structures, each with unique attributes.

Topic Objectives

Topic 8: Imperfect Competition

In this Topic, you will learn about:

- How Monopolies form: Barriers to Entry

- How a Profit-Maximizing Monopoly Chooses Output and Price

- Monopolistic Competition

Since firms have no influence on the market price in a perfectly competitive market, price = marginal revenue, which is constant regardless of the production level. This means the firm produces where price = marginal cost.

In a competitive market, firms are unable to increase their prices above equilibrium without losing at least some customers. In reality, we know that this is often not the case. Clothing brands, for example, can sell items for much higher than what they cost to make, whereas other firms that are selling similar products at a lower price struggle to get by. This is in part due to the number of firms in a market and in a firm’s ability to distinguish its products from its competitors.

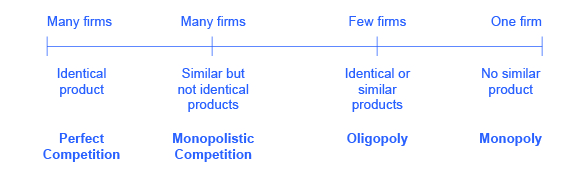

Firms face different competitive situations. At one extreme—perfect competition—many firms are all trying to sell identical products. At the other extreme—monopoly—only one firm is selling the product, and this firm faces no competition. Monopolistic competition and oligopoly fall between the two extremes. Monopolistic competition is a situation with many firms selling similar, but not identical, products. Oligopoly is a situation with few firms that sell identical or similar products.

We analyzed perfect competition in depth in Topic 7. Now, let’s view the other extreme and examine a firm’s behaviour without competition.