8.2 Fixing Monopoly

Learning Objectives

- Explain how Price Discrimination can correct market failure

- Suggest government policies to remove the deadweight loss associated with monopoly

In Topic 4, we learned about the different government policies that can change quantity (in those cases resulting in a deadweight loss) and showed how these can be helpful to correct failures due to externalities. Now, we will apply those concepts to see how we can correct monopolies.

Price Discrimination

Before looking at how policy can be used to correct a monopoly, let’s first consider a simpler solution. In the last section, we introduced a single price monopoly, saying that the monopolist must charge the same price to all consumers. In reality, monopolists tend to practice price discrimination meaning they charge a different price to different consumers, with the aim of charging the maximum of each consumer’s willingness to pay.

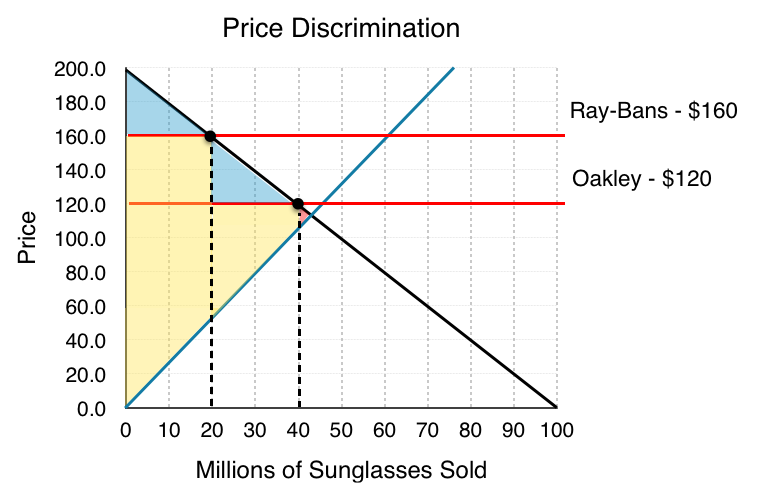

This is seen in practice in many different ways. The most common is price discrimination based on demographics. Discounts for seniors or children who are willing to pay less for the good allow the monopolist to still capture revenue from these consumers. Companies may also create slightly different offerings or brands to appeal to different crowds. Luxottica, for example, sells higher priced Ray-Bans to cater to a more fashion-conscious crowd, and Oakley caters to consumers who care more about functionality. Let’s look at how the different price points affect market surplus.

In this situation, Luxottica sells sunglasses at two different prices: Ray-Bans at $160 and Oakleys at $120. Notice the effect this has on producer surplus. Whereas at $140 Luxottica sold 30 million units, at the two prices it can sell 40 million, and the average price of the sunglasses is still $140 million. This benefits some consumers who can purchase sunglasses at the lower cost but hurts some who now have to pay a higher price. The deadweight loss has shrunk considerably.

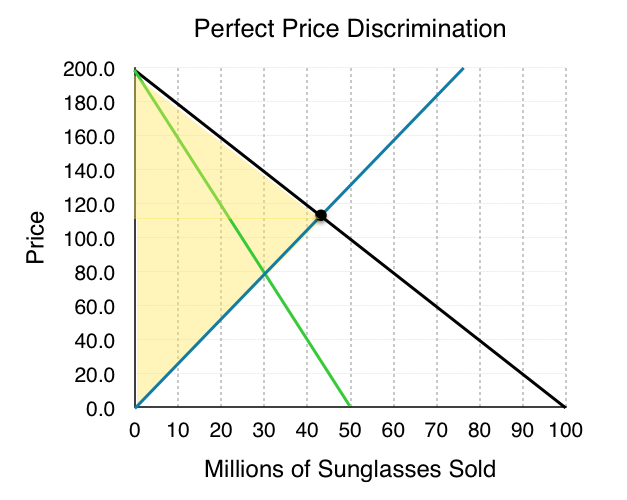

Can we ever remove the deadweight loss entirely? For the producer, this would be preferred as the more it can differentiate prices, the more surplus it receives. Consider a case where the producer can charge the exact willingness to pay of each consumer, a perfect price discrimination.

As we can see, the deadweight loss has been completely negated, but so has consumer surplus. The monopolist ultimately aims for this situation but is often prohibited from doing so by the difficulty of breaking consumers into segments, government regulation, and more. For a monopoly, we will assume from now on that monopolists can only charge one price.

Government Policy & Monopoly

How can the government correct a monopoly? Remember that to correct the deadweight loss and return to an efficient outcome, we must return QE to 42 million sunglasses. This means that we need a policy that will increase quantity. Taxes and price floors, in this case, would decrease quantity, so they will be ineffective. A subsidy would be difficult to implement. Even though it would increase market surplus, it would have the interesting effect of giving the monopolist, who is already charging consumers more that the competitive equilibrium price, more revenue.

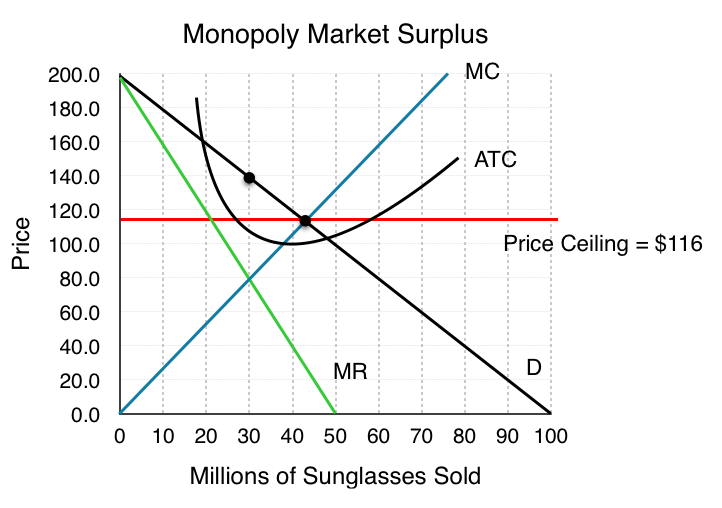

This leaves us with a price ceiling, which can be fairly effective in removing deadweight loss. In the figure below, we have included the ATC to give a more in-depth picture of how the monopolist behaves.

A binding price floor at $116 would indeed remove the DWL and bring the market almost back to a competitive equilibrium, but with one key difference. In this equilibrium, ATC is not minimized. Why does this matter if there is no DWL? If the market became open to competition, firms entering the market would cause each demand to shift inwards and would cause aggregate MC to fall as firms were able to take advantage of a lower ATC. This would bring the price down and make consumers better off. The result is that even with market correction, the market equilibrium is still too small.

Glossary

- Perfect Price Discrimination

- the action of selling the same product at a different price to each consumer, equal to their maximum willingness to pay

- Price Discrimination

- the action of selling the same product at different price to maximize profits

Exercises 8.2

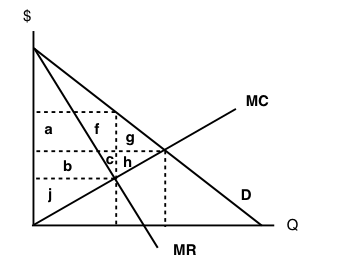

The following TWO questions refer to the diagram below, which illustrates the demand, marginal revenue, and marginal cost curves for a profit-maximizing single-price monopolist.

1. Which area represents the deadweight loss due to the monopoly?

a) g + h.

b) f + g.

c) f + c.

d) f + g + c+ h.

2. Which area represents the monopolist’s producer surplus?

a) a + b + f.

b) a + b + f + c.

c) a + b + f + c + j.

d) a + b + j.