18. Innate Nonspecific Host Defenses

18.1 Physical Defences

Learning Objectives

- Describe the various physical barriers and mechanical defences that protect the human body against infection and disease

- Describe the role of microbiota as a first-line defence against infection and disease

Angela, a 25-year-old female patient in the emergency department, is having some trouble communicating verbally because of shortness of breath. A nurse observes constriction and swelling of the airway and labored breathing. The nurse asks Angela if she has a history of asthma or allergies. Angela shakes her head no, but there is fear in her eyes. With some difficulty, she explains that her father died suddenly at age 27, when she was just a little girl, of a similar respiratory attack. The underlying cause had never been identified.

- What are some possible causes of constriction and swelling of the airway?

- What causes swelling of body tissues in general?

Jump to the next Clinical Focus box.

Nonspecific innate immunity can be characterized as a multifaceted system of defences that targets invading pathogens in a nonspecific manner. In this chapter, we have divided the numerous defences that make up this system into three categories: physical defences, chemical defences, and cellular defences. However, it is important to keep in mind that these defences do not function independently, and the categories often overlap. Table 18.1 provides an overview of the nonspecific defences discussed in this chapter.

Table 18.1. Overview of Nonspecific Innate Immune Defences

| Overview of Nonspecific Innate Immune Defences | |

|---|---|

| Physical defences | Physical barriers |

| Mechanical defences | |

| Microbiome | |

| Chemical defences | Chemicals and enzymes in body fluids |

| Antimicrobial peptides | |

| Plasma protein mediators | |

| Cytokines | |

| Inflammation-eliciting mediators | |

| Cellular defences | Granulocytes |

| Agranulocytes | |

Physical defences provide the body’s most basic form of nonspecific defence. They include physical barriers to microbes, such as the skin and mucous membranes, as well as mechanical defences that physically remove microbes and debris from areas of the body where they might cause harm or infection. In addition, the microbiome provides a measure of physical protection against disease, as microbes of the normal microbiota compete with pathogens for nutrients and cellular binding sites necessary to cause infection.

Physical Barriers

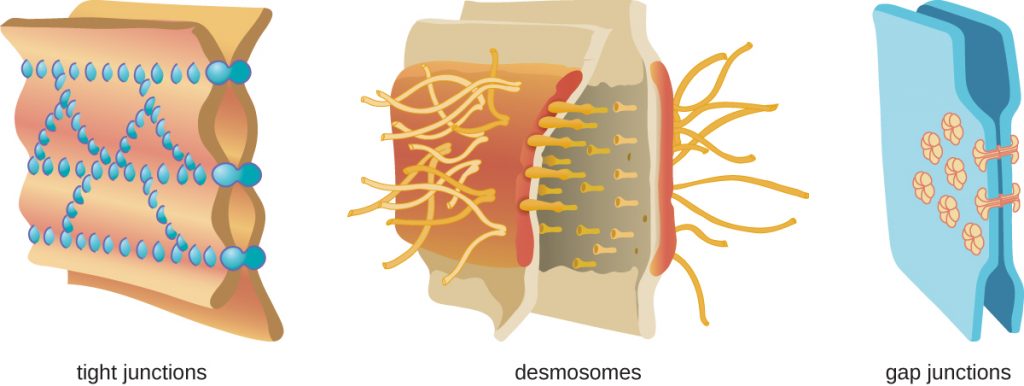

Physical barriers play an important role in preventing microbes from reaching tissues that are susceptible to infection. At the cellular level, barriers consist of cells that are tightly joined to prevent invaders from crossing through to deeper tissue. For example, the endothelial cells that line blood vessels have very tight cell-to-cell junctions, blocking microbes from gaining access to the bloodstream. Cell junctions are generally composed of cell membrane proteins that may connect with the extracellular matrix or with complementary proteins from neighbouring cells. Tissues in various parts of the body have different types of cell junctions. These include tight junctions, desmosomes, and gap junctions, as illustrated in Figure 1. Invading microorganisms may attempt to break down these substances chemically, using enzymes such as proteases that can cause structural damage to create a point of entry for pathogens.

The Skin Barrier

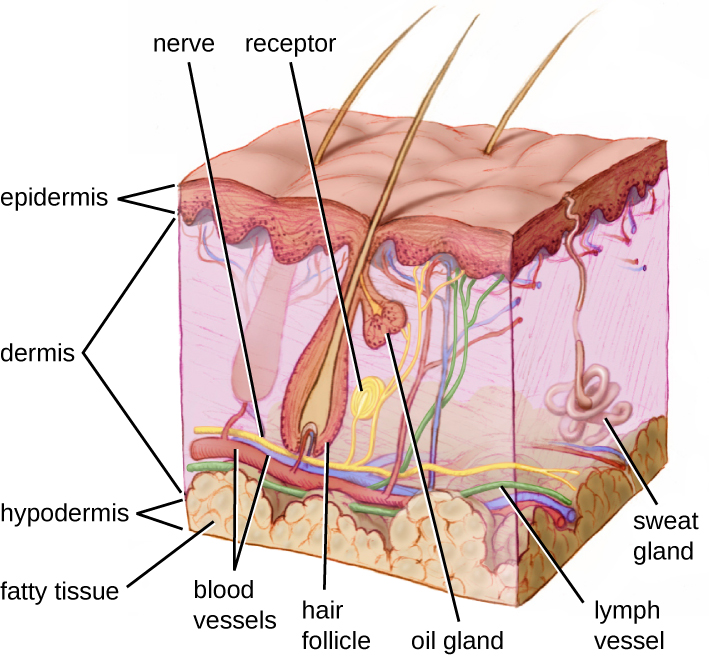

One of the body’s most important physical barriers is the skin barrier, which is composed of three layers of closely packed cells. The thin upper layer is called the epidermis. A second, thicker layer, called the dermis, contains hair follicles, sweat glands, nerves, and blood vessels. A layer of fatty tissue called the hypodermis lies beneath the dermis and contains blood and lymph vessels (Figure 18.3).

The topmost layer of skin, the epidermis, consists of cells that are packed with keratin. These dead cells remain as a tightly connected, dense layer of protein-filled cell husks on the surface of the skin. The keratin makes the skin’s surface mechanically tough and resistant to degradation by bacterial enzymes. Fatty acids on the skin’s surface create a dry, salty, and acidic environment that inhibits the growth of some microbes and is highly resistant to breakdown by bacterial enzymes. In addition, the dead cells of the epidermis are frequently shed, along with any microbes that may be clinging to them. Shed skin cells are continually replaced with new cells from below, providing a new barrier that will soon be shed in the same way.

Infections can occur when the skin barrier is compromised or broken. A wound can serve as a point of entry for opportunistic pathogens, which can infect the skin tissue surrounding the wound and possibly spread to deeper tissues.

CASE IN POINT: Every Rose Has its Thorns

Mike, a gardener from southern California, recently noticed a small red bump on his left forearm. Initially, he did not think much of it, but soon it grew larger and then ulcerated (opened up), becoming a painful lesion that extended across a large part of his forearm (Figure 18.4). He went to an urgent care facility, where a physician asked about his occupation. When he said he was a landscaper, the physician immediately suspected a case of sporotrichosis, a type of fungal infection known as rose gardener’s disease because it often afflicts landscapers and gardening enthusiasts.

Under most conditions, fungi cannot produce skin infections in healthy individuals. Fungi grow filaments known as hyphae, which are not particularly invasive and can be easily kept at bay by the physical barriers of the skin and mucous membranes. However, small wounds in the skin, such as those caused by thorns, can provide an opening for opportunistic pathogens like Sporothrix schenkii, a soil-dwelling fungus and the causative agent of rose gardener’s disease. Once it breaches the skin barrier, S. schenkii can infect the skin and underlying tissues, producing ulcerated lesions like Mike’s. Compounding matters, other pathogens may enter the infected tissue, causing secondary bacterial infections.

Luckily, rose gardener’s disease is treatable. Mike’s physician wrote him a prescription for some anti-fungal drugs as well as a course of antibiotics to combat secondary bacterial infections. His lesions eventually healed, and Mike returned to work with a new appreciation for gloves and protective clothing.

Mucous Membranes

The mucous membranes lining the nose, mouth, lungs, and urinary and digestive tracts provide another nonspecific barrier against potential pathogens. Mucous membranes consist of a layer of epithelial cells bound by tight junctions. The epithelial cells secrete a moist, sticky substance called mucus, which covers and protects the more fragile cell layers beneath it and traps debris and particulate matter, including microbes. Mucus secretions also contain antimicrobial peptides.

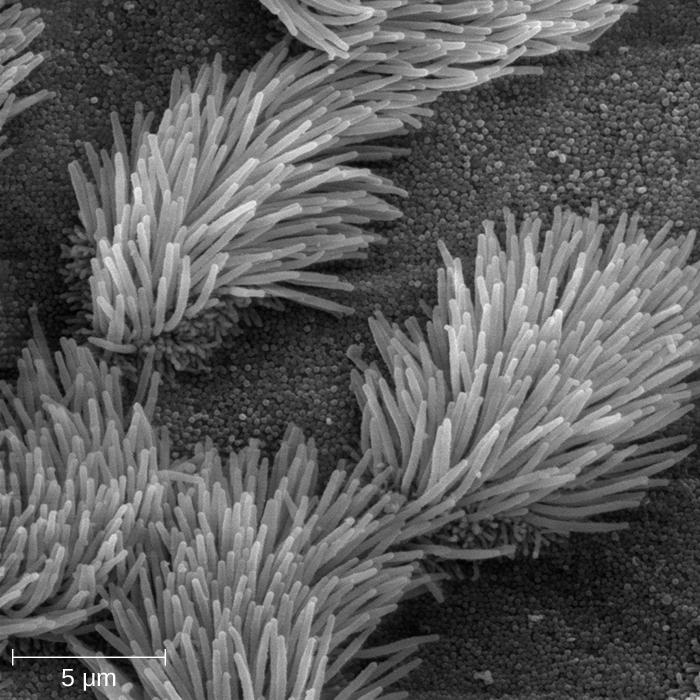

In many regions of the body, mechanical actions serve to flush mucus (along with trapped or dead microbes) out of the body or away from potential sites of infection. For example, in the respiratory system, inhalation can bring microbes, dust, mould spores, and other small airborne debris into the body. This debris becomes trapped in the mucus lining the respiratory tract, a layer known as the mucociliary blanket. The epithelial cells lining the upper parts of the respiratory tract are called ciliated epithelial cells because they have hair-like appendages known as cilia. Movement of the cilia propels debris-laden mucus out and away from the lungs. The expelled mucus is then swallowed and destroyed in the stomach, or coughed up, or sneezed out (Figure 18.5). This system of removal is often called the mucociliary escalator.

The mucociliary escalator is such an effective barrier to microbes that the lungs, the lowermost (and most sensitive) portion of the respiratory tract, were long considered to be a sterile environment in healthy individuals. Only recently has research suggested that healthy lungs may have a small normal microbiota. Disruption of the mucociliary escalator by the damaging effects of smoking or diseases such as cystic fibrosis can lead to increased colonization of bacteria in the lower respiratory tract and frequent infections, which highlights the importance of this physical barrier to host defences.

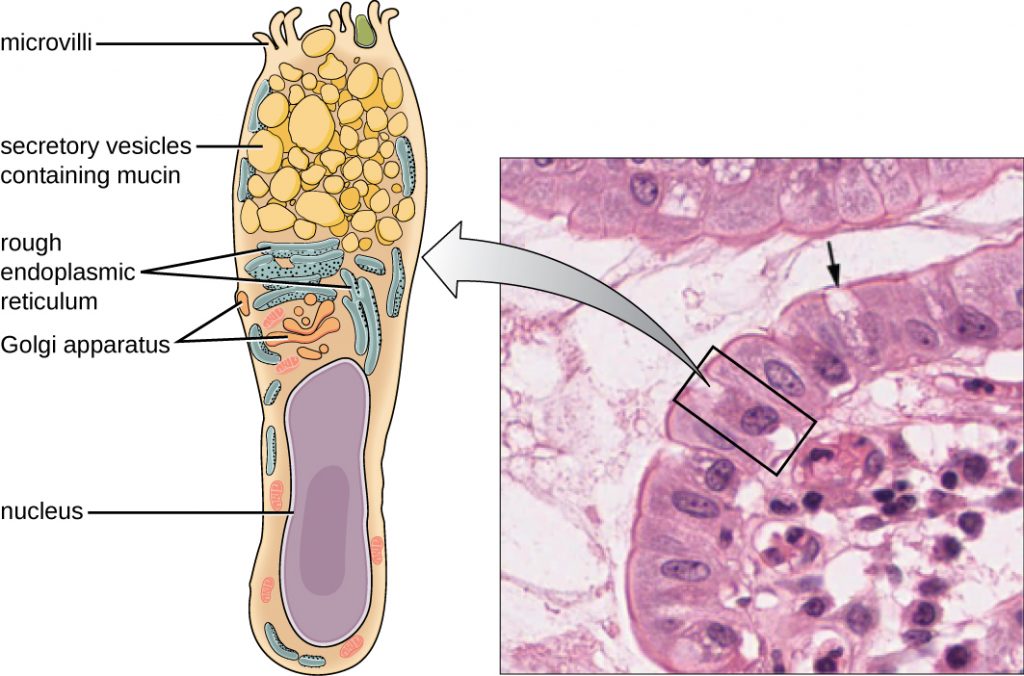

Like the respiratory tract, the digestive tract is a portal of entry through which microbes enter the body, and the mucous membranes lining the digestive tract provide a nonspecific physical barrier against ingested microbes. The intestinal tract is lined with epithelial cells, interspersed with mucus-secreting goblet cells (Figure 18.6). This mucus mixes with material received from the stomach, trapping food-borne microbes and debris. The mechanical action of peristalsis, a series of muscular contractions in the digestive tract, moves the sloughed mucus and other material through the intestines, rectum, and anus, excreting the material in faeces.

Endothelia

The epithelial cells lining the urogenital tract, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and certain other tissues are known as endothelia. These tightly packed cells provide a particularly effective frontline barrier against invaders. The endothelia of the blood-brain barrier, for example, protect the central nervous system (CNS), which consists of the brain and the spinal cord. The CNS is one of the most sensitive and important areas of the body, as microbial infection of the CNS can quickly lead to serious and often fatal inflammation. The cell junctions in the blood vessels traveling through the CNS are some of the tightest and toughest in the body, preventing any transient microbes in the bloodstream from entering the CNS. This keeps the cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds and bathes the brain and spinal cord sterile under normal conditions.

- Describe how the mucociliary escalator functions.

- Name two places you would find endothelia.

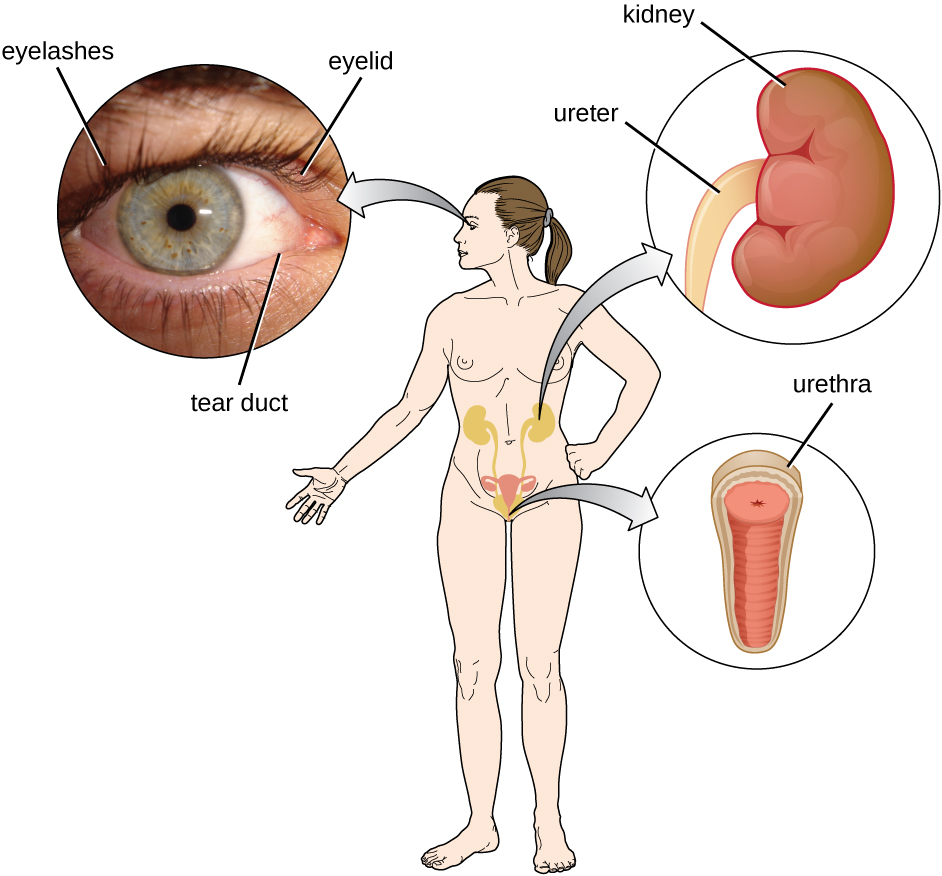

Mechanical Defences

In addition to physical barriers that keep microbes out, the body has a number of mechanical defences that physically remove pathogens from the body, preventing them from taking up residence. We have already discussed several examples of mechanical defences, including the shedding of skin cells, the expulsion of mucus via the mucociliary escalator, and the excretion of faeces through intestinal peristalsis. Other important examples of mechanical defences include the flushing action of urine and tears, which both serve to carry microbes away from the body. The flushing action of urine is largely responsible for the normally sterile environment of the urinary tract, which includes the kidneys, ureters, and urinary bladder. Urine passing out of the body washes out transient microorganisms, preventing them from taking up residence. The eyes also have physical barriers and mechanical mechanisms for preventing infections. The eyelashes and eyelids prevent dust and airborne microorganisms from reaching the surface of the eye. Any microbes or debris that make it past these physical barriers may be flushed out by the mechanical action of blinking, which bathes the eye in tears, washing debris away (Figure 18.7).

- Name two mechanical defences that protect the eyes.

Microbiome

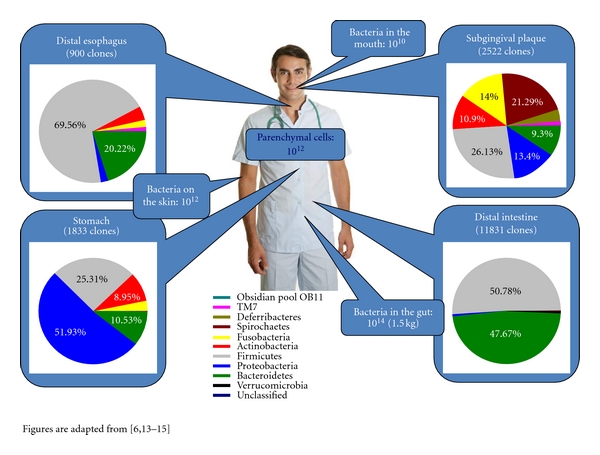

In various regions of the body, resident microbiota[1] serve as an important first-line defence against invading pathogens (Figure 18.8). Through their occupation of cellular binding sites and competition for available nutrients, the resident microbiota prevent the critical early steps of pathogen attachment and proliferation required for the establishment of an infection. For example, in the vagina, members of the resident microbiota compete with opportunistic pathogens like the yeast Candida. This competition prevents infections by limiting the availability of nutrients, thus inhibiting the growth of Candida, keeping its population in check. Similar competitions occur between the microbiota and potential pathogens on the skin, in the upper respiratory tract, and in the gastrointestinal tract. As will be discussed later in this chapter, the resident microbiota also contribute to the chemical defences of the innate nonspecific host defences.

The importance of the normal microbiota in host defences is highlighted by the increased susceptibility to infectious diseases when the microbiota is disrupted or eliminated. Treatment with antibiotics can significantly deplete the normal microbiota of the gastrointestinal tract, providing an advantage for pathogenic bacteria to colonize and cause diarrhoeal infections, including the severe diarrhoea and pseudomembranous colitis caused by Clostridium difficile (“C. diff”). C. difficile infections are potentially lethal; one strategy for treating these infections is faecal transplantation, which involves the transfer of faecal material from a donor (screened for potential pathogens) into the intestines of the recipient patient as a method of restoring the normal microbiota. More recently, Microbial Ecosystem Therapy is being developed as a safer alternative.

Table 18.2 provides a summary of the physical defences discussed in this section.

Table 18.2. Physical Defences of Nonspecific Innate Immunity

| Physical Defences of Nonspecific Innate Immunity | ||

|---|---|---|

| Defence | Examples | Function |

| Cellular barriers | Skin, mucous membranes, endothelial cells | Deny entry to pathogens |

| Mechanical defences | Shedding of skin cells, mucociliary sweeping, peristalsis, flushing action of urine and tears | Remove pathogens from potential sites of infection |

| Microbiome | Resident bacteria of the skin, upper respiratory tract, gastrointestinal tract, and genitourinary tract | Compete with pathogens for cellular binding sites and nutrients |

- List two ways resident microbiota defend against pathogens.

Key Takeaways

- Nonspecific innate immunity provides a first line of defence against infection by nonspecifically blocking entry of microbes and targeting them for destruction or removal from the body.

- The physical defences of innate immunity include physical barriers, mechanical actions that remove microbes and debris, and the microbiome, which competes with and inhibits the growth of pathogens.

- The skin, mucous membranes, and endothelia throughout the body serve as physical barriers that prevent microbes from reaching potential sites of infection. Tight cell junctions in these tissues prevent microbes from passing through.

- Microbes trapped in dead skin cells or mucus are removed from the body by mechanical actions such as shedding of skin cells, mucociliary sweeping, coughing, peristalsis, and flushing of bodily fluids (e.g., urination, tears)

- The resident microbiota provide a physical defence by occupying available cellular binding sites and competing with pathogens for available nutrients.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- Differentiate a physical barrier from a mechanical removal mechanism and give an example of each.

- Identify some ways that pathogens can breach the physical barriers of the innate immune system.

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_17_02_Junction

- OSC_Microbio_17_02_Skin

- OSC_Microbio_17_02_Sporotrich

- OSC_Microbio_17_02_Cilia

- OSC_Microbio_17_02_GobletCell

- OSC_Microbio_17_02_Barrier

- Human microbiota is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Harris, K., Kassis, A., Major, G. and Chou, C.J. "Is the Gut Microbiota a New Factor Contributing to Obesity and Its Metabolic Disorders?" J. Obes. 2012; 2012: 879151. ↵