15. Antimicrobial Drugs

15.4 Mechanisms of Other Antimicrobial Drugs

Learning Objective

- Explain the differences between modes of action of drugs that target fungi, protozoa, helminths, and viruses

Because fungi, protozoa, and helminths are eukaryotic, their cells are very similar to human cells, making it more difficult to develop drugs with selective toxicity. Additionally, viruses replicate within human host cells, making it difficult to develop drugs that are selectively toxic to viruses or virus-infected cells. Despite these challenges, there are antimicrobial drugs that target fungi, protozoa, helminths, and viruses, and some even target more than one type of microbe. Tables 15.7-15.9 provide examples for antimicrobial drugs in these various classes.

Antifungal Drugs

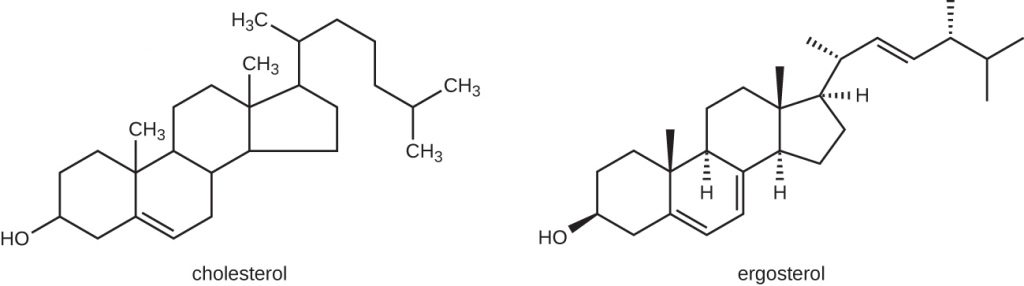

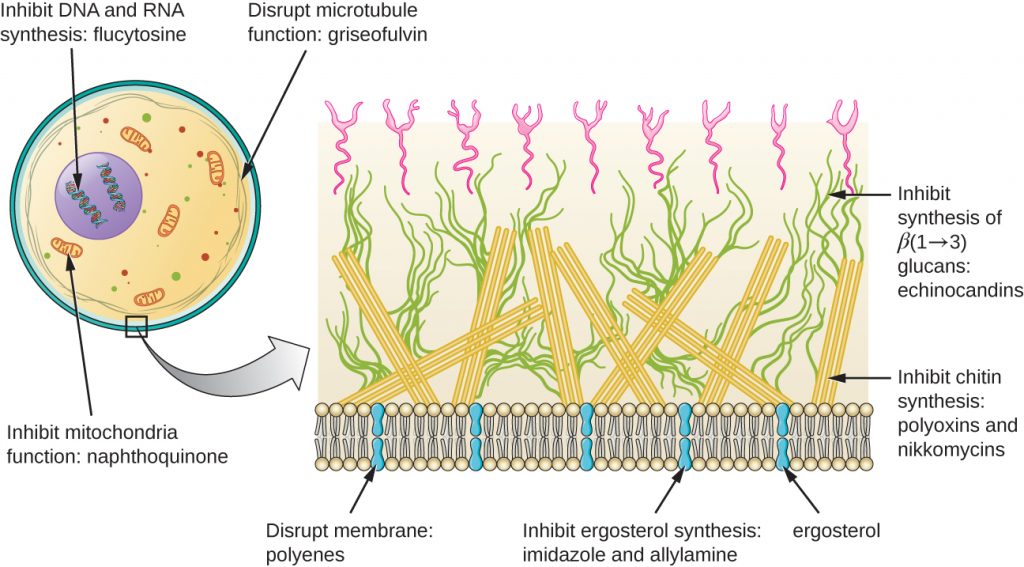

The most common mode of action for antifungal drugs is the disruption of the cell membrane. Antifungals take advantage of small differences between fungi and humans in the biochemical pathways that synthesize sterols. The sterols are important in maintaining proper membrane fluidity and, hence, proper function of the cell membrane. For most fungi, the predominant membrane sterol is ergosterol. Because human cell membranes use cholesterol, instead of ergosterol, antifungal drugs that target ergosterol synthesis are selectively toxic (Figure 15.13).

The imidazoles are synthetic fungicides that disrupt ergosterol biosynthesis; they are commonly used in medical applications and also in agriculture to keep seeds and harvested crops from moulding. Examples include miconazole, ketoconazole, and clotrimazole, which are used to treat fungal skin infections such as ringworm, specifically tinea pedis (athlete’s foot), tinea cruris (jock itch), and tinea corporis. These infections are commonly caused by dermatophytes of the genera Trichophyton, Epidermophyton, and Microsporum. Miconazole is also used predominantly for the treatment of vaginal yeast infections caused by the fungus Candida, and ketoconazole is used for the treatment of tinea versicolour and dandruff, which both can be caused by the fungus Malassezia.

The triazole drugs, including fluconazole, also inhibit ergosterol biosynthesis. However, they can be administered orally or intravenously for the treatment of several types of systemic yeast infections, including oral thrush and cryptococcal meningitis, both of which are prevalent in patients with AIDS. The triazoles also exhibit more selective toxicity, compared with the imidazoles, and are associated with fewer side effects.

The allylamines, a structurally different class of synthetic antifungal drugs, inhibit an earlier step in ergosterol biosynthesis. The most commonly used allylamine is terbinafine (marketed under the brand name Lamisil), which is used topically for the treatment of dermatophytic skin infections like athlete’s foot, ringworm, and jock itch. Oral treatment with terbinafine is also used for the treatment of fingernail and toenail fungus, but it can be associated with the rare side effect of hepatotoxicity.

The polyenes are a class of antifungal agents naturally produced by certain actinomycete soil bacteria and are structurally related to macrolides. These large, lipophilic molecules bind to ergosterol in fungal cytoplasmic membranes, thus creating pores. Common examples include nystatin and amphotericin B. Nystatin is typically used as a topical treatment for yeast infections of the skin, mouth, and vagina, but may also be used for intestinal fungal infections. The drug amphotericin B is used for systemic fungal infections like aspergillosis, cryptococcal meningitis, histoplasmosis, blastomycosis, and candidiasis. Amphotericin B was the only antifungal drug available for several decades, but its use is associated with some serious side effects, including nephrotoxicity (kidney toxicity).

Amphotericin B is often used in combination with flucytosine, a fluorinated pyrimidine analog that is converted by a fungal-specific enzyme into a toxic product that interferes with both DNA replication and protein synthesis in fungi. Flucytosine is also associated with hepatotoxicity (liver toxicity) and bone marrow depression.

Beyond targeting ergosterol in fungal cell membranes, there are a few antifungal drugs that target other fungal structures (Figure 15.14). The echinocandins, including caspofungin, are a group of naturally produced antifungal compounds that block the synthesis of β(1→3) glucan found in fungal cell walls but not found in human cells. This drug class has the nickname “penicillin for fungi.” Caspofungin is used for the treatment of aspergillosis as well as systemic yeast infections.

Although chitin is only a minor constituent of fungal cell walls, it is also absent in human cells, making it a selective target. The polyoxins and nikkomycins are naturally produced antifungals that target chitin synthesis. Polyoxins are used to control fungi for agricultural purposes, and nikkomycin Z is currently under development for use in humans to treat yeast infections and Valley fever (coccidioidomycosis), a fungal disease prevalent in the southwestern US.[1]

The naturally produced antifungal griseofulvin is thought to specifically disrupt fungal cell division by interfering with microtubules involved in spindle formation during mitosis. It was one of the first antifungals, but its use is associated with hepatotoxicity. It is typically administered orally to treat various types of dermatophytic skin infections when other topical antifungal treatments are ineffective.

There are a few drugs that act as antimetabolites against fungal processes. For example, atovaquone, a representative of the naphthoquinone drug class, is a semisynthetic antimetabolite for fungal and protozoal versions of a mitochondrial cytochrome important in electron transport. Structurally, it is an analog of coenzyme Q, with which it competes for electron binding. It is particularly useful for the treatment of Pneumocystis pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii. The antibacterial sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim combination also acts as an antimetabolite against P. jirovecii.

Table 15.7 shows the various therapeutic classes of antifungal drugs, categorized by mode of action, with examples of each.

Table 15.7. Common Antifungal Drugs

| Common Antifungal Drugs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Drug Class | Specific Drugs | Clinical Uses |

| Inhibit ergosterol synthesis | Imidazoles | Miconazole, ketoconazole, clotrimazole | Fungal skin infections and vaginal yeast infections |

| Triazoles | Fluconazole | Systemic yeast infections, oral thrush, and cryptococcal meningitis | |

| Allylamines | Terbinafine | Dermatophytic skin infections (athlete’s foot, ring worm, jock itch), and infections of fingernails and toenails | |

| Bind ergosterol in the cell membrane and create pores that disrupt the membrane | Polyenes | Nystatin | Used topically for yeast infections of skin, mouth, and vagina; also used for fungal infections of the intestine |

| Amphotericin B | Variety systemic fungal infections | ||

| Inhibit cell wall synthesis | Echinocandins | Caspofungin | Aspergillosis and systemic yeast infections |

| Not applicable | Nikkomycin Z | Coccidioidomycosis (Valley fever) and yeast infections | |

| Inhibit microtubules and cell division | Not applicable | Griseofulvin | Dermatophytic skin infections |

- How is disruption of ergosterol biosynthesis an effective mode of action for antifungals?

CASE IN POINT: Treating a Fungal Infection of the Lungs

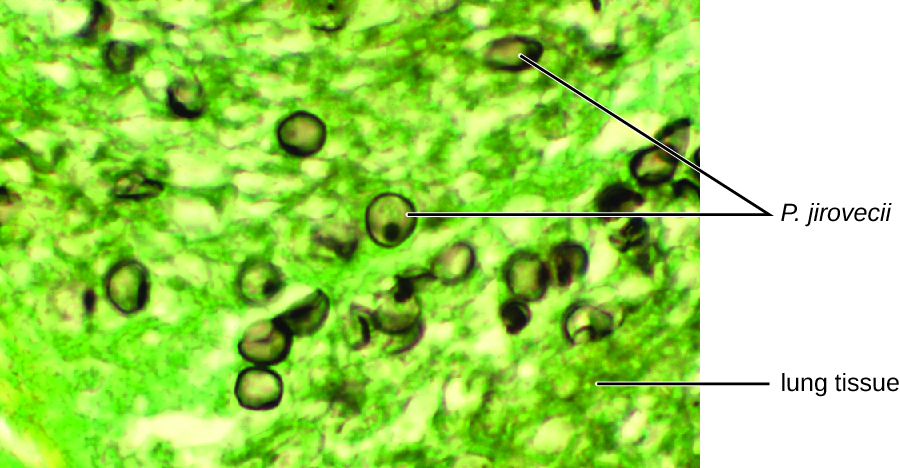

Jack, a 48-year-old engineer, is HIV positive but generally healthy thanks to antiretroviral therapy (ART). However, after a particularly intense week at work, he developed a fever and a dry cough. He assumed that he just had a cold or mild flu due to overexertion and didn’t think much of it. However, after about a week, he began to experience fatigue, weight loss, and shortness of breath. He decided to visit his physician, who found that Jack had a low level of blood oxygenation. The physician ordered blood testing, a chest X-ray, and the collection of an induced sputum sample for analysis. His X-ray showed a fine cloudiness and several pneumatoceles (thin-walled pockets of air), which indicated Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP), a type of pneumonia caused by the fungus Pneumocystis jirovecii. Jack’s physician admitted him to the hospital and prescribed Bactrim, a combination of sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim, to be administered intravenously.

P. jirovecii is a yeast-like fungus with a life cycle similar to that of protozoans. As such, it was classified as a protozoan until the 1980s. It lives only in the lung tissue of infected persons and is transmitted from person to person, with many people exposed as children. Typically, P. jirovecii only causes pneumonia in immunocompromised individuals. Healthy people may carry the fungus in their lungs with no symptoms of disease. PCP is particularly problematic among HIV patients with compromised immune systems.

PCP is usually treated with oral or intravenous Bactrim, but atovaquone or pentamidine (another antiparasitic drug) are alternatives. If not treated, PCP can progress, leading to a collapsed lung and nearly 100% mortality. Even with antimicrobial drug therapy, PCP still is responsible for 10% of HIV-related deaths.

The cytological examination, using direct immunofluorescence assay (DFA), of a smear from Jack’s sputum sample confirmed the presence of P. jirovecii (Figure 15.15). Additionally, the results of Jack’s blood tests revealed that his white blood cell count had dipped, making him more susceptible to the fungus. His physician reviewed his ART regimen and made adjustments. After a few days of hospitalization, Jack was released to continue his antimicrobial therapy at home. With the adjustments to his ART therapy, Jack’s CD4 counts began to increase and he was able to go back to work.

Antiprotozoan Drugs

There are a few mechanisms by which antiprotozoan drugs target infectious protozoans (Table 15.8). Some are antimetabolites, such as atovaquone, proguanil, and artemisinins. Atovaquone, in addition to being antifungal, blocks electron transport in protozoans and is used for the treatment of protozoan infections including malaria, babesiosis, and toxoplasmosis. Proguanil is another synthetic antimetabolite that is processed in parasitic cells into its active form, which inhibits protozoan folic acid synthesis. It is often used in combination with atovaquone, and the combination is marketed as Malarone for both malaria treatment and prevention.

Artemisinin, a plant-derived antifungal first discovered by Chinese scientists in the 1970s, is quite effective against malaria. Semisynthetic derivatives of artemisinin are more water soluble than the natural version, which makes them more bioavailable. Although the exact mechanism of action is unclear, artemisinins appear to act as prodrugs that are metabolized by target cells to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage target cells. Due to the rise in resistance to antimalarial drugs, artemisinins are also commonly used in combination with other antimalarial compounds in artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT).

Several antimetabolites are used for the treatment of toxoplasmosis caused by the parasite Toxoplasma gondii. The synthetic sulfa drug sulfadiazine competitively inhibits an enzyme in folic acid production in parasites and can be used to treat malaria and toxoplasmosis. Pyrimethamine is a synthetic drug that inhibits a different enzyme in the folic acid production pathway and is often used in combination with sulfadoxine (another sulfa drug) for the treatment of malaria or in combination with sulfadiazine for the treatment of toxoplasmosis. Side effects of pyrimethamine include decreased bone marrow activity that may cause increased bruising and low red blood cell counts. When toxicity is a concern, spiramycin, a macrolide protein synthesis inhibitor, is typically administered for the treatment of toxoplasmosis.

Two classes of antiprotozoan drugs interfere with nucleic acid synthesis: nitroimidazoles and quinolines. Nitroimidazoles, including semisynthetic metronidazole, which was discussed previously as an antibacterial drug, and synthetic tinidazole, are useful in combating a wide variety of protozoan pathogens, such as Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Trichomonas vaginalis. Upon introduction into these cells in low-oxygen environments, nitroimidazoles become activated and introduce DNA strand breakage, interfering with DNA replication in target cells. Unfortunately, metronidazole is associated with carcinogenesis (the development of cancer) in humans.

Another type of synthetic antiprotozoan drug that has long been thought to specifically interfere with DNA replication in certain pathogens is pentamidine. It has historically been used for the treatment of African sleeping sickness (caused by the protozoan Trypanosoma brucei) and leishmaniasis (caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania), but it is also an alternative treatment for the fungus Pneumocystis. Some studies indicate that it specifically binds to the DNA found within kinetoplasts (kDNA; long mitochondrion-like structures unique to trypanosomes), leading to the cleavage of kDNA. However, nuclear DNA of both the parasite and host remain unaffected. It also appears to bind to tRNA, inhibiting the addition of amino acids to tRNA, thus preventing protein synthesis. Possible side effects of pentamidine use include pancreatic dysfunction and liver damage.

The quinolines are a class of synthetic compounds related to quinine, which has a long history of use against malaria. Quinolines are thought to interfere with heme detoxification, which is necessary for the parasite’s effective breakdown of hemoglobin into amino acids inside red blood cells. The synthetic derivatives chloroquine, quinacrine (also called mepacrine), and mefloquine are commonly used as antimalarials, and chloroquine is also used to treat amebiasis typically caused by Entamoeba histolytica. Long-term prophylactic use of chloroquine or mefloquine may result in serious side effects, including hallucinations or cardiac issues. Patients with glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency experience severe anaemia when treated with chloroquine.

Table 15.8. Common Antiprotozoan Drugs

| Common Antiprotozoan Drugs | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Drug Class | Specific Drugs | Clinical Uses |

| Inhibit electron transport in mitochondria | Naphthoquinone | Atovaquone | Malaria, babesiosis, and toxoplasmosis |

| Inhibit folic acid synthesis | Not applicable | Proquanil | Combination therapy with atovaquone for malaria treatment and prevention |

| Sulfonamide | Sulfadiazine | Malaria and toxoplasmosis | |

| Not applicable | Pyrimethamine | Combination therapy with sulfadoxine (sulfa drug) for malaria | |

| Produces damaging reactive oxygen species | Not applicable | Artemisinin | Combination therapy to treat malaria |

| Inhibit DNA synthesis | Nitroimidazoles | Metronidazole, tinidazole | Infections caused by Giardia lamblia, Entamoeba histolytica, and Trichomonas vaginalis |

| Not applicable | Pentamidine | African sleeping sickness and leishmaniasis | |

| Inhibit heme detoxification | Quinolines | Chloroquine | Malaria and infections with E. histolytica |

| Mepacrine, mefloquine | Malaria | ||

- List two modes of action for antiprotozoan drugs.

Antiviral Drugs

Unlike the complex structure of fungi, protozoa, and helminths, viral structure is simple, consisting of nucleic acid, a protein coat, viral enzymes, and, sometimes, a lipid envelope. Furthermore, viruses are obligate intracellular pathogens that use the host’s cellular machinery to replicate. These characteristics make it difficult to develop drugs with selective toxicity against viruses.

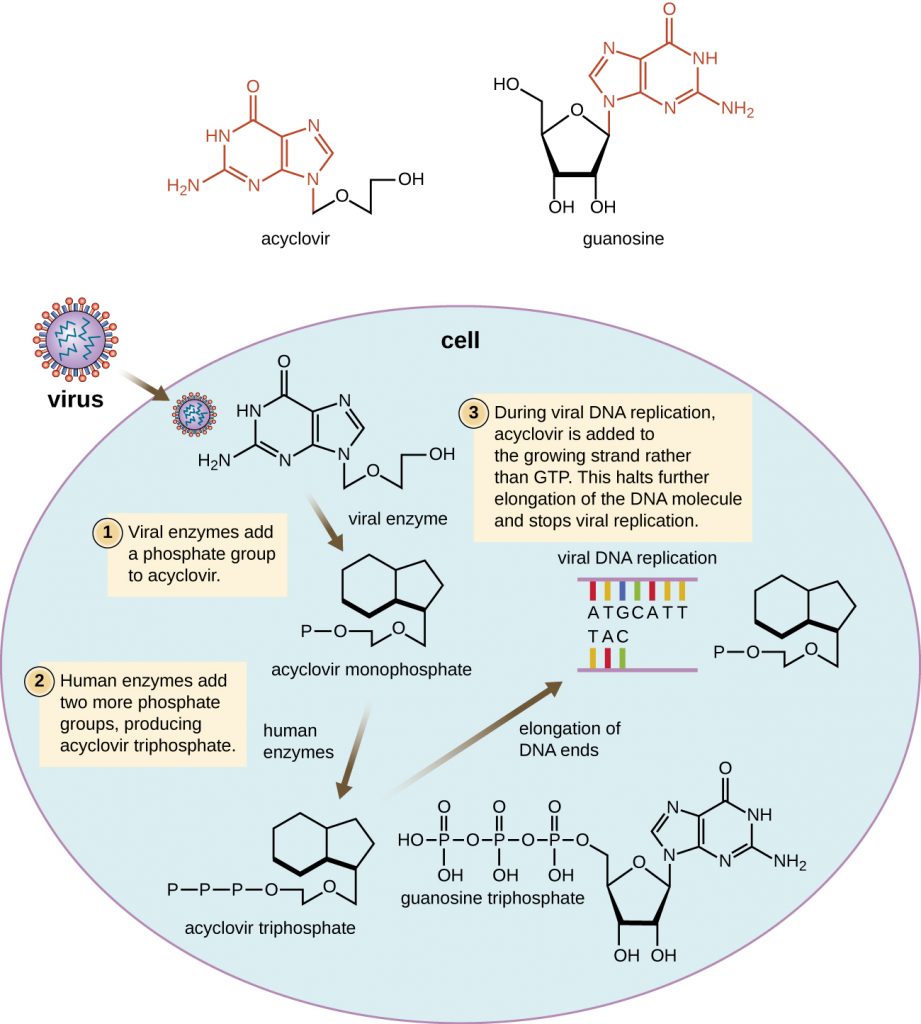

Many antiviral drugs are nucleoside analogs and function by inhibiting nucleic acid biosynthesis. For example, acyclovir (marketed as Zovirax) is a synthetic analog of the nucleoside guanosine (Figure 15.18). It is activated by the herpes simplex viral enzyme thymidine kinase and, when added to a growing DNA strand during replication, causes chain termination. Its specificity for virus-infected cells comes from both the need for a viral enzyme to activate it and the increased affinity of the activated form for viral DNA polymerase compared to host cell DNA polymerase. Acyclovir and its derivatives are frequently used for the treatment of herpes virus infections, including genital herpes, chickenpox, shingles, Epstein-Barr virus infections, and cytomegalovirus infections. Acyclovir can be administered either topically or systemically, depending on the infection. One possible side effect of its use includes nephrotoxicity. The drug adenine-arabinoside, marketed as vidarabine, is a synthetic analog to deoxyadenosine that has a mechanism of action similar to that of acyclovir. It is also effective for the treatment of various human herpes viruses. However, because of possible side effects involving low white blood cell counts and neurotoxicity, treatment with acyclovir is now preferred.

Ribavirin, another synthetic guanosine analog, works by a mechanism of action that is not entirely clear. It appears to interfere with both DNA and RNA synthesis, perhaps by reducing intracellular pools of guanosine triphosphate (GTP). Ribavarin also appears to inhibit the RNA polymerase of hepatitis C virus. It is primarily used for the treatment of the RNA viruses like hepatitis C (in combination therapy with interferon) and respiratory syncytial virus. Possible side effects of ribavirin use include anaemia and developmental effects on unborn children in pregnant patients. In recent years, another nucleotide analog, sofosbuvir (Solvaldi), has also been developed for the treatment of hepatitis C. Sofosbuvir is a uridine analog that interferes with viral polymerase activity. It is commonly coadministered with ribavirin, with and without interferon.

Inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis is not the only target of synthetic antivirals. Although the mode of action of amantadine and its relative rimantadine are not entirely clear, these drugs appear to bind to a transmembrane protein that is involved in the escape of the influenza virus from endosomes. Blocking escape of the virus also prevents viral RNA release into host cells and subsequent viral replication. Increasing resistance has limited the use of amantadine and rimantadine in the treatment of influenza A. Use of amantadine can result in neurological side effects, but the side effects of rimantadine seem less severe. Interestingly, because of their effects on brain chemicals such as dopamine and NMDA (N-methyl D-aspartate), amantadine and rimantadine are also used for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease.

Neuraminidase inhibitors, including olsetamivir (Tamiflu), zanamivir (Relenza), and peramivir (Rapivab), specifically target influenza viruses by blocking the activity of influenza virus neuraminidase, preventing the release of the virus from infected cells. These three antivirals can decrease flu symptoms and shorten the duration of illness, but they differ in their modes of administration: olsetamivir is administered orally, zanamivir is inhaled, and peramivir is administered intravenously. Resistance to these neuraminidase inhibitors still seems to be minimal.

Pleconaril is a synthetic antiviral under development that showed promise for the treatment of picornaviruses. Use of pleconaril for the treatment of the common cold caused by rhinoviruses was not approved by the FDA in 2002 because of lack of proven effectiveness, lack of stability, and association with irregular menstruation. Its further development for this purpose was halted in 2007. However, pleconaril is still being investigated for use in the treatment of life-threatening complications of enteroviruses, such as meningitis and sepsis. It is also being investigated for use in the global eradication of a specific enterovirus, polio.[2] Pleconaril seems to work by binding to the viral capsid and preventing the uncoating of viral particles inside host cells during viral infection.

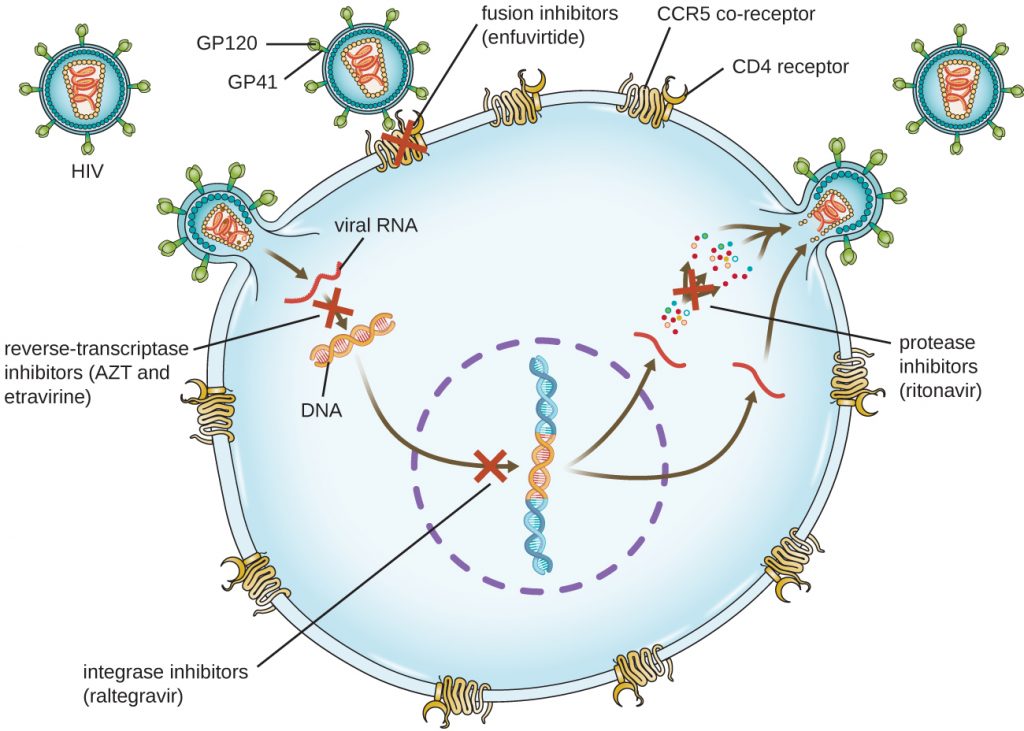

Viruses with complex life cycles, such as HIV, can be more difficult to treat. First, HIV targets CD4-positive white blood cells, which are necessary for a normal immune response to infection. Second, HIV is a retrovirus, meaning that it converts its RNA genome into a DNA copy that integrates into the host cell’s genome, thus hiding within host cell DNA. Third, the HIV reverse transcriptase lacks proofreading activity and introduces mutations that allow for rapid development of antiviral drug resistance. To help prevent the emergence of resistance, a combination of specific synthetic antiviral drugs is typically used in ART for HIV (Figure 15.17).

The reverse transcriptase inhibitors block the early step of converting viral RNA genome into DNA, and can include competitive nucleoside analog inhibitors (e.g., azidothymidine/zidovudine, or AZT) and non-nucleoside noncompetitive inhibitors (e.g., etravirine) that bind reverse transcriptase and cause an inactivating conformational change. Drugs called protease inhibitors (e.g., ritonavir) block the processing of viral proteins and prevent viral maturation. Protease inhibitors are also being developed for the treatment of other viral types.[3] For example, simeprevir (Olysio) has been approved for the treatment of hepatitis C and is administered with ribavirin and interferon in combination therapy. The integrase inhibitors (e.g., raltegravir), block the activity of the HIV integrase responsible for the recombination of a DNA copy of the viral genome into the host cell chromosome. Additional drug classes for HIV treatment include the CCR5 antagonists and the fusion inhibitors (e.g., enfuviritide), which prevent the binding of HIV to the host cell coreceptor (chemokine receptor type 5 [CCR5]) and the merging of the viral envelope with the host cell membrane, respectively. Table 3 shows the various therapeutic classes of antiviral drugs, categorized by mode of action, with examples of each.

Table 15.9. Common Antiviral Drugs

| Common Antiviral Drugs | ||

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Drug | Clinical Uses |

| Nucleoside analog inhibition of nucleic acid synthesis | Acyclovir | Herpes virus infections |

| Azidothymidine/zidovudine (AZT) | HIV infections | |

| Ribavirin | Hepatitis C virus and respiratory syncytial virus infections | |

| Vidarabine | Herpes virus infections | |

| Sofosbuvir | Hepatitis C virus infections | |

| Non-nucleoside noncompetitive inhibition | Etravirine | HIV infections |

| Inhibit escape of virus from endosomes | Amantadine, rimantadine | Infections with influenza virus |

| Inhibit neuraminadase | Olsetamivir, zanamivir, peramivir | Infections with influenza virus |

| Inhibit viral uncoating | Pleconaril | Serious enterovirus infections |

| Inhibition of protease | Ritonavir | HIV infections |

| Simeprevir | Hepatitis C virus infections | |

| Inhibition of integrase | Raltegravir | HIV infections |

| Inhibition of membrane fusion | Enfuviritide | HIV infections |

- Why is HIV difficult to treat with antivirals?

To learn more about the various classes of antiretroviral drugs used in the ART of HIV infection, explore each of the drugs in the HIV drug classes provided by US Department of Health and Human Services at this website.

Key Takeaways

- Because fungi, protozoans, and helminths are eukaryotic organisms like human cells, it is more challenging to develop antimicrobial drugs that specifically target them. Similarly, it is hard to target viruses because human viruses replicate inside of human cells.

- Antifungal drugs interfere with ergosterol synthesis, bind to ergosterol to disrupt fungal cell membrane integrity, or target cell wall-specific components or other cellular proteins.

- Antiprotozoan drugs increase cellular levels of reactive oxygen species, interfere with protozoal DNA replication (nuclear versus kDNA, respectively), and disrupt heme detoxification.

- Antihelminthic drugs disrupt helminthic and protozoan microtubule formation; block neuronal transmissions; inhibit anaerobic ATP formation and/or oxidative phosphorylation; induce a calcium influx in tapeworms, leading to spasms and paralysis; and interfere with RNA synthesis in schistosomes.

- Antiviral drugs inhibit viral entry, inhibit viral uncoating, inhibit nucleic acid biosynthesis, prevent viral escape from endosomes in host cells, and prevent viral release from infected cells.

- Because it can easily mutate to become drug resistant, HIV is typically treated with a combination of several antiretroviral drugs, which may include reverse transcriptase inhibitors, protease inhibitors, integrase inhibitors, and drugs that interfere with viral binding and fusion to initiate infection.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

True/False

Short Answer

- How does the biology of HIV necessitate the need to treat HIV infections with multiple drugs?

- Niclosamide is insoluble and thus is not readily absorbed from the stomach into the bloodstream. How does the insolubility of niclosamide aid its effectiveness as a treatment for tapeworm infection?

Critical Thinking

- Why can’t drugs used to treat influenza, like amantadines and neuraminidase inhibitors, be used to treat a wider variety of viral infections?

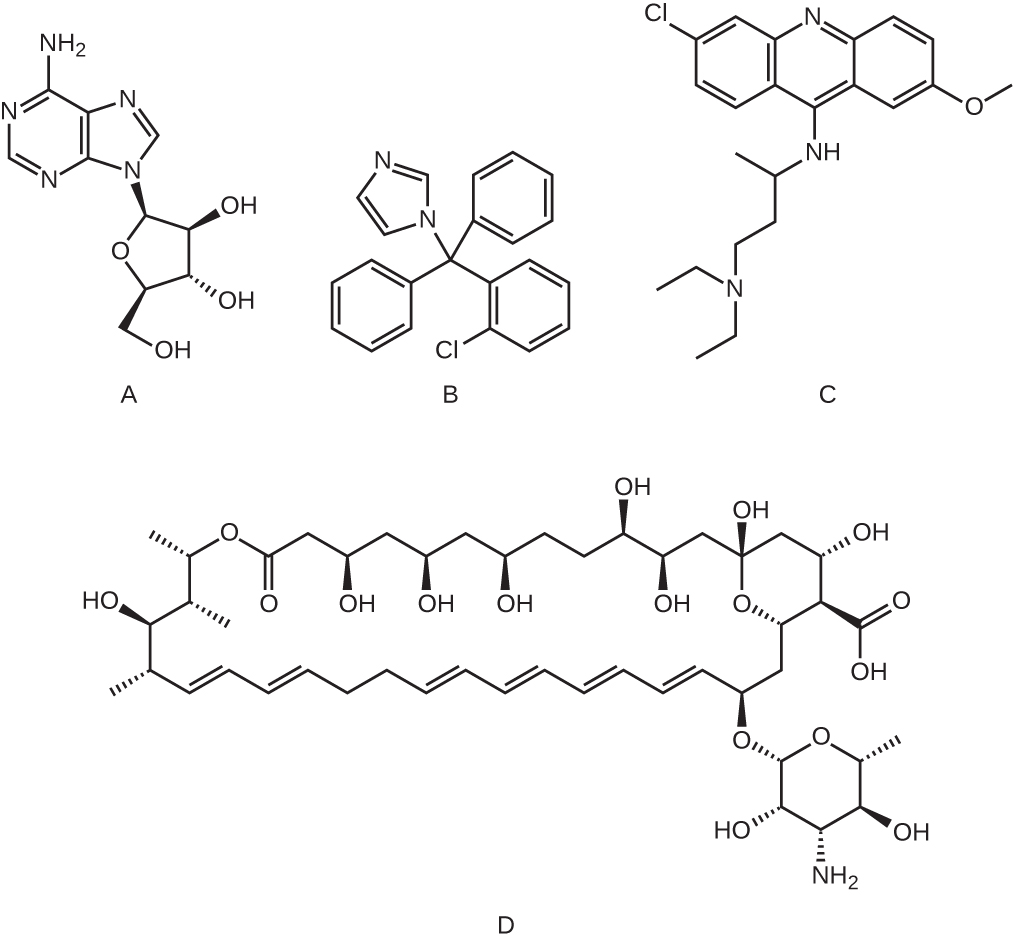

- Which of the following molecules is an example of a nucleoside analog?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_14_03_sterols

- OSC_Microbio_14_03_antifungal

- OSC_Microbio_14_03_Acyclovir

- OSC_Microbio_14_03_ART

- microbiology sign © Nick Youngson

- OSC_Microbio_14_03_nucleoside_img

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Valley Fever: Awareness Is Key.” http://www.cdc.gov/features/valleyfever/. Accessed May 13, 20196. ↵

- M.J. Abzug. “The Enteroviruses: Problems in Need of Treatments.” Journal of Infection 68 no. S1 (2014):108–14. ↵

- B.L. Pearlman. “Protease Inhibitors for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Genotype-1 Infection: The New Standard of Care.” Lancet Infectious Diseases 12 no. 9 (2012):717–728. ↵