1. An Invisible World

1.1 What Our Ancestors Knew

Learning Objectives

- Describe how our ancestors improved food with the use of microbes

- Describe how the causes of sickness and disease were explained in ancient times, prior to the invention of the microscope

- Describe key historical events and people associated with the birth of microbiology and microbial ecology

Clinical Focus: Part 1

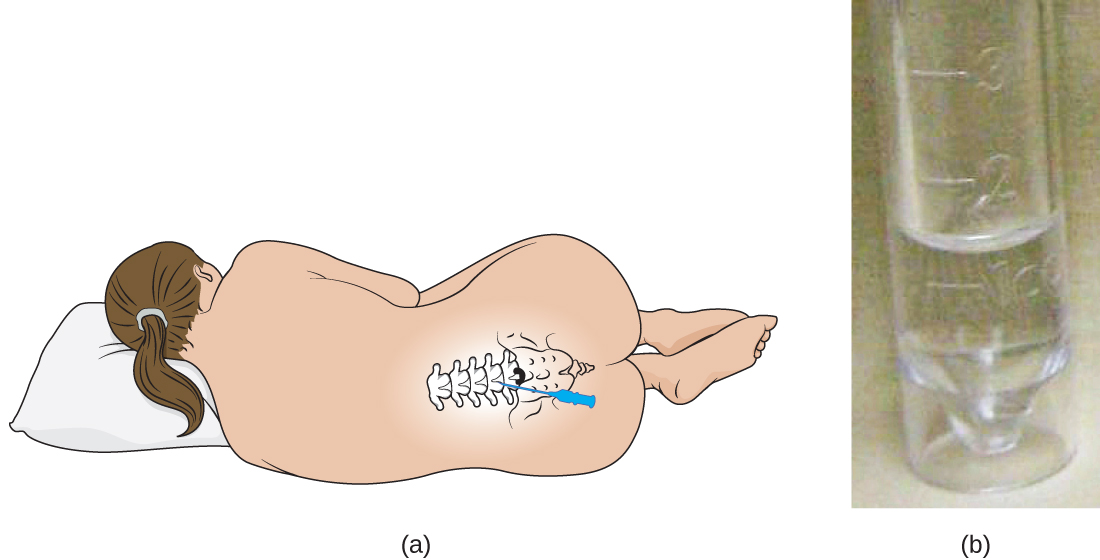

Cora, a 41-year-old lawyer and mother of two, has recently been experiencing severe headaches, a high fever, and a stiff neck. Her husband, who has accompanied Cora to see a doctor, reports that Cora also seems confused at times and unusually drowsy. Based on these symptoms, the doctor suspects that Cora may have meningitis, a potentially life-threatening infection of the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord.

Meningitis has several potential causes. It can be brought on by bacteria, fungi, viruses, or even a reaction to medication or exposure to heavy metals. Although people with viral meningitis usually heal on their own, bacterial and fungal meningitis are quite serious and require treatment.

Cora’s doctor orders a lumbar puncture (spinal tap) to take three samples of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from around the spinal cord (Figure 1.2). The samples will be sent to laboratories in three different departments for testing: clinical chemistry, microbiology, and haematology. The samples will first be visually examined to determine whether the CSF is abnormally coloured or cloudy; then the CSF will be examined under a microscope to see if it contains a normal number of red and white blood cells and to check for any abnormal cell types. In the microbiology lab, the specimen will be centrifuged to concentrate any cells in a sediment; this sediment will be smeared on a slide and stained with a Gram stain. Gram staining is a procedure used to differentiate between two different types of bacteria (Gram-positive and Gram-negative).

About 80% of patients with bacterial meningitis will show bacteria in their CSF with a Gram stain.[1]

Cora’s Gram stain did not show any bacteria, but her doctor decides to prescribe her antibiotics just in case. Part of the CSF sample will be cultured—put in special dishes to see if bacteria or fungi will grow. It takes some time for most microorganisms to reproduce in sufficient quantities to be detected and analyzed.

- What types of microorganisms would be killed by antibiotic treatment?

Jump to the next Clinical Focus box.

Most people today, even those who know very little about microbiology, are familiar with the concept of microbes, or “germs,” and their role in human health. Schoolchildren learn about bacteria, viruses, and other microorganisms, and many even view specimens under a microscope. But a few hundred years ago, before the invention of the microscope, the existence of many types of microbes was impossible to prove. By definition, microorganisms, or microbes, are very small organisms; many types of microbes are too small to see without a microscope, although some parasites and fungi are visible to the naked eye.

Humans have been living with—and using—microorganisms for much longer than they have been able to see them. Historical evidence suggests that humans have had some notion of microbial life since prehistoric times and have used that knowledge to develop foods as well as prevent and treat disease. In this section, we will explore some of the historical applications of microbiology as well as the early beginnings of microbiology as a science.

Fermented Foods and Beverages

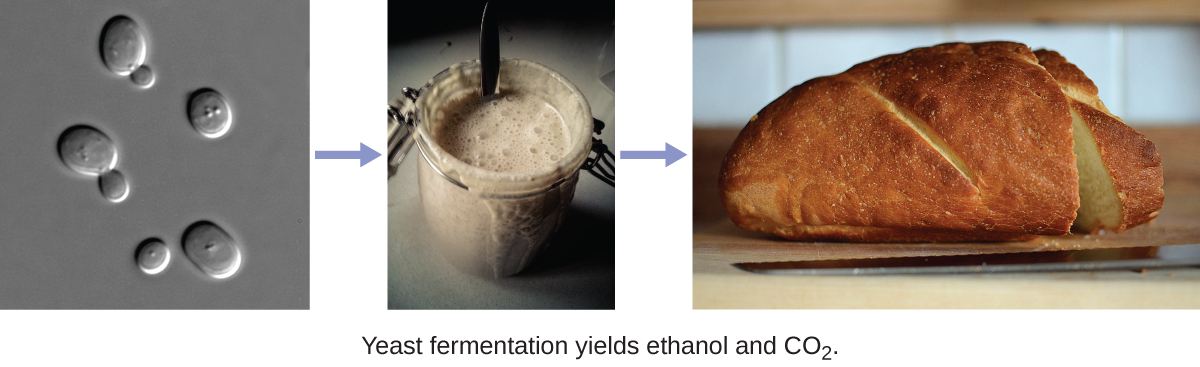

People across the world have enjoyed fermented foods and beverages like beer, wine, bread, yogurt, cheese, and pickled vegetables for all of recorded history. Discoveries from several archeological sites suggest that even prehistoric people took advantage of fermentation to preserve and enhance the taste of food. Archaeologists studying pottery jars from a Neolithic village in China found that people were making a fermented beverage from rice, honey, and fruit as early as 7000 BC.[2]

Production of these foods and beverages requires microbial fermentation, a process that uses bacteria, mould, or yeast to convert sugars (carbohydrates) to alcohol, gases, and organic acids (Figure 1.3). While it is likely that people first learned about fermentation by accident—perhaps by drinking old milk that had curdled or old grape juice that had fermented—they later learned to harness the power of fermentation to make products like bread, cheese, and wine.

The Iceman Treateth

Prehistoric humans had a very limited understanding of the causes of disease, and various cultures developed different beliefs and explanations. While many believed that illness was punishment for angering the gods or was simply the result of fate, archaeological evidence suggests that prehistoric people attempted to treat illnesses and infections. One example of this is Ötzi the Iceman, a 5300-year-old mummy found frozen in the ice of the Ötzal Alps on the Austrian-Italian border in 1991. Because Ötzi was so well preserved by the ice, researchers discovered that he was infected with the eggs of the parasite Trichuris trichiura, which may have caused him to have abdominal pain and anaemia. Researchers also found evidence of Borrelia burgdorferi, a bacterium that causes Lyme disease.[3] Some researchers think Ötzi may have been trying to treat his infections with the woody fruit of the Piptoporus betulinus fungus, which was discovered tied to his belongings.[4] This fungus has both laxative and antibiotic properties. Ötzi was also covered in tattoos that were made by cutting incisions into his skin, filling them with herbs, and then burning the herbs. There is speculation that this may have been another attempt to treat his health ailments.

Early Notions of Disease, Contagion, and Containment

Several ancient civilizations appear to have had some understanding that disease could be transmitted by things they could not see. This is especially evident in historical attempts to contain the spread of disease. For example, the Bible refers to the practice of quarantining people with leprosy and other diseases, suggesting that people understood that diseases could be communicable. Ironically, while leprosy is communicable, it is also a disease that progresses slowly. This means that people were likely quarantined after they had already spread the disease to others.

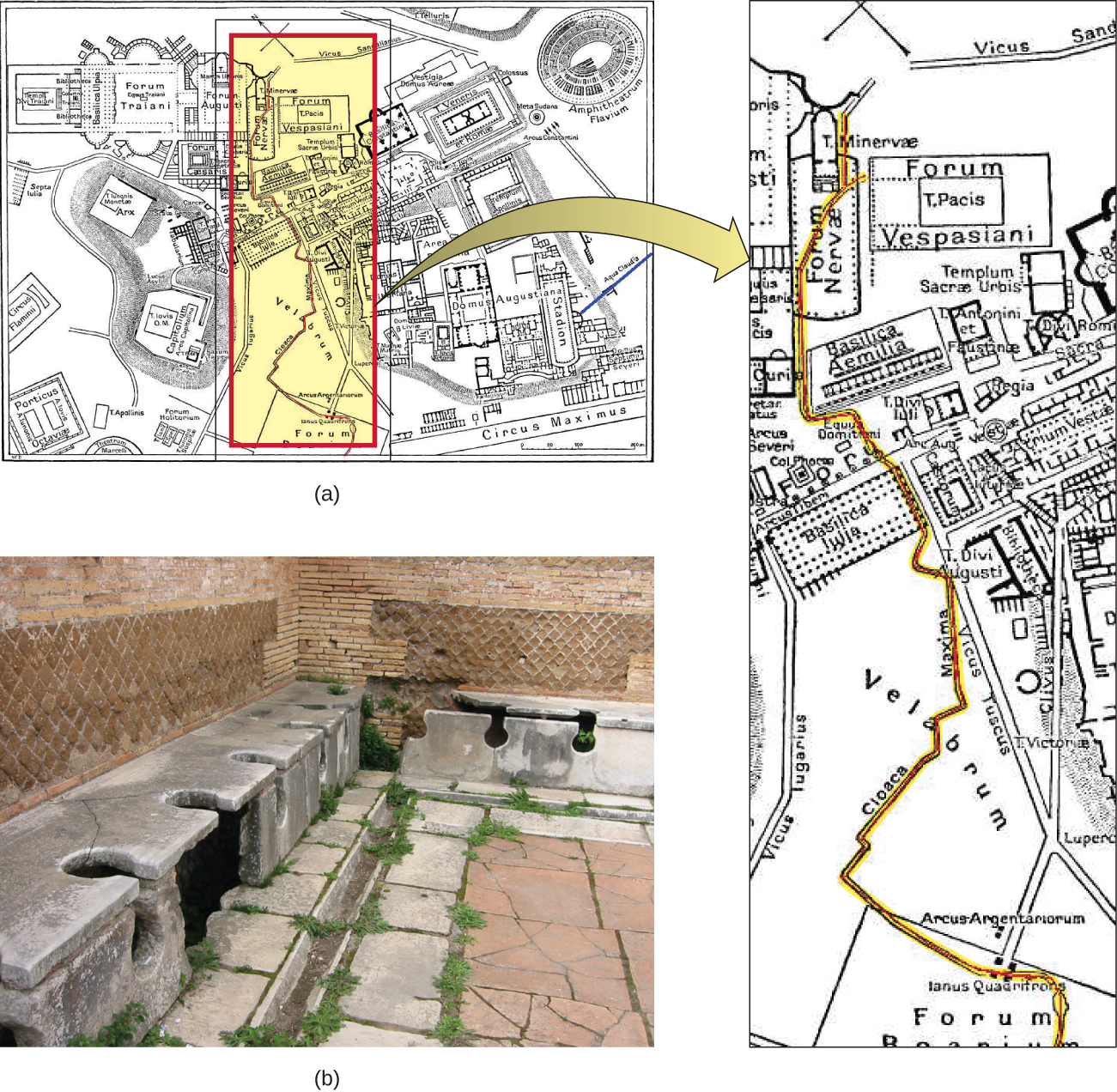

The ancient Greeks attributed disease to bad air, mal’aria, which they called “miasmatic odours.” They developed hygiene practices that built on this idea. The Romans also believed in the miasma hypothesis and created a complex sanitation infrastructure to deal with sewage. In Rome, they built aqueducts, which brought fresh water into the city, and a giant sewer, the Cloaca Maxima, which carried waste away and into the river Tiber (Figure 1.4). Some researchers believe that this infrastructure helped protect the Romans from epidemics of waterborne illnesses.

Even before the invention of the microscope, some doctors, philosophers, and scientists made great strides in understanding the invisible forces—what we now know as microbes—that can cause infection, disease, and death.

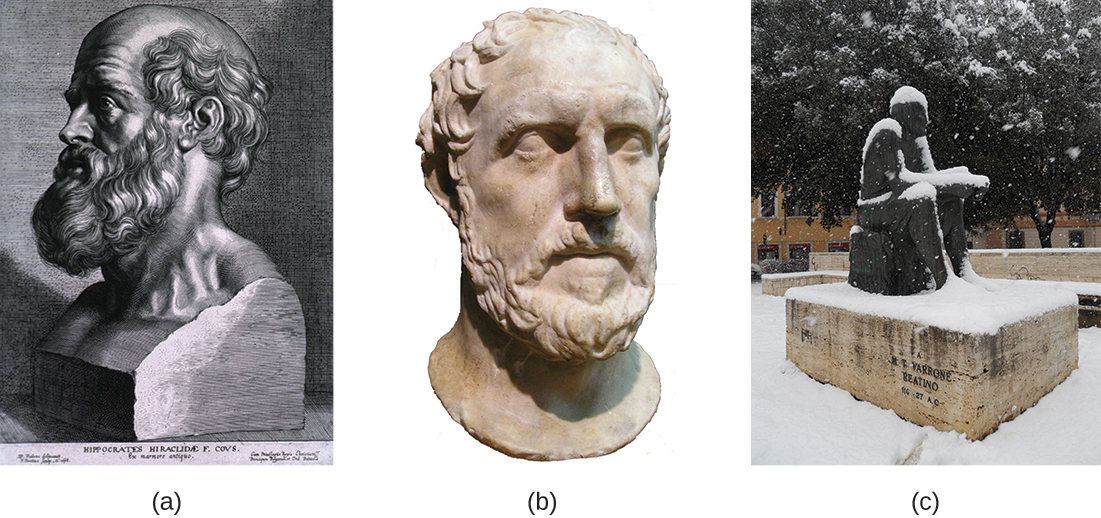

The Greek physician Hippocrates (460–370 BC) is considered the “father of Western medicine” (Figure 1.5). Unlike many of his ancestors and contemporaries, he dismissed the idea that disease was caused by supernatural forces. Instead, he posited that diseases had natural causes from within patients or their environments. Hippocrates and his heirs are believed to have written the Hippocratic Corpus, a collection of texts that make up some of the oldest surviving medical books.[5] Hippocrates is also often credited as the author of the Hippocratic Oath, taken by new physicians to pledge their dedication to diagnosing and treating patients without causing harm.

While Hippocrates is considered the father of Western medicine, the Greek philosopher and historian Thucydides (460–395 BC) is considered the father of scientific history because he advocated for evidence-based analysis of cause-and-effect reasoning (Figure 1.5). Among his most important contributions are his observations regarding the Athenian plague that killed one-third of the population of Athens between 430 and 410 BC. Having survived the epidemic himself, Thucydides made the important observation that survivors did not get re-infected with the disease, even when taking care of actively sick people.[6] This observation shows an early understanding of the concept of immunity.

Marcus Terentius Varro (116–27 BC) was a prolific Roman writer who was one of the first people to propose the concept that things we cannot see (what we now call microorganisms) can cause disease (Figure 1.5). In Res Rusticae (On Farming), published in 36 BC, he said that “precautions must also be taken in neighbourhood swamps . . . because certain minute creatures [animalia minuta] grow there which cannot be seen by the eye, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases.”[7]

- Give two examples of foods that have historically been produced by humans with the aid of microbes.

- Explain how historical understandings of disease contributed to attempts to treat and contain disease.

The Birth of Microbiology

While the ancients may have suspected the existence of invisible “minute creatures,” it wasn’t until the invention of the microscope that their existence was definitively confirmed. While it is unclear who exactly invented the microscope, a Dutch cloth merchant named Antonie van Leeuwenhoek (1632–1723) was the first to develop a lens powerful enough to view microbes. In 1675, using a simple but powerful microscope, Leeuwenhoek was able to observe single-celled organisms, which he described as “animalcules” or “wee little beasties,” swimming in a drop of rain water. From his drawings of these little organisms, we now know he was looking at bacteria and protists. (We will explore Leeuwenhoek’s contributions to microscopy further in How We See the Invisible World.)

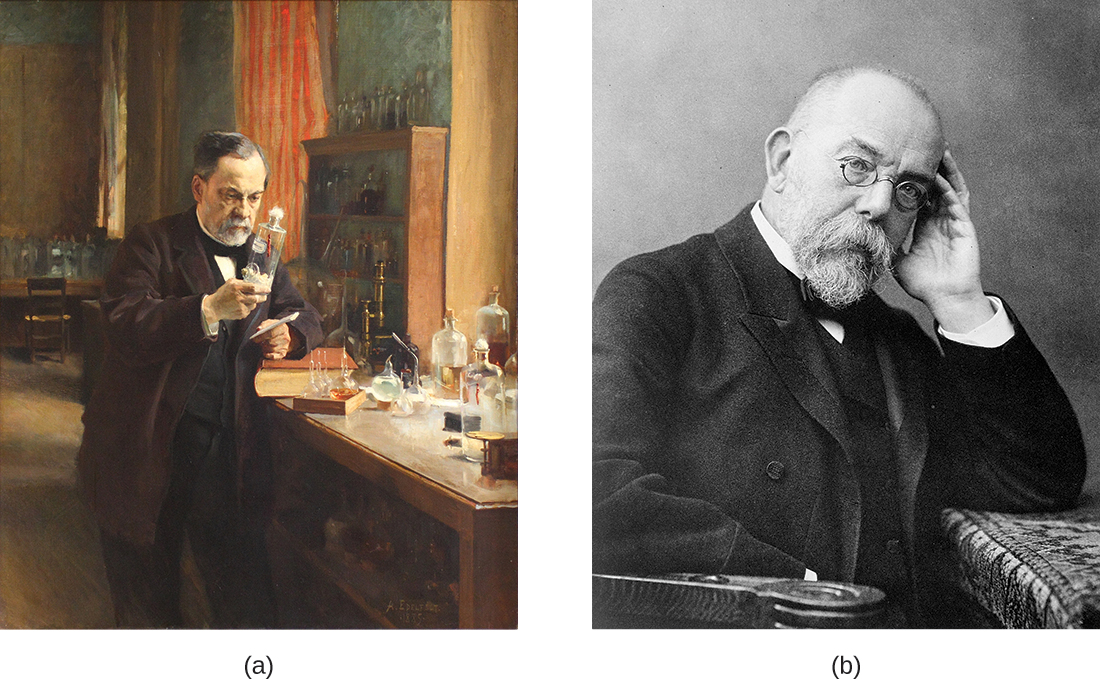

Nearly 200 years after van Leeuwenhoek got his first glimpse of microbes, the “Golden Age of Microbiology” spawned a host of new discoveries between 1857 and 1914. Two famous microbiologists, Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, were especially active in advancing our understanding of the unseen world of microbes (Figure 1.6). Pasteur, a French chemist, showed that individual microbial strains had unique properties and demonstrated that fermentation is caused by microorganisms. He also invented pasteurization, a process used to kill microorganisms responsible for spoilage, and developed vaccines for the treatment of diseases, including rabies, in animals and humans. Koch, a German physician, was the first to demonstrate the connection between a single, isolated microbe and a known human disease. For example, he discovered the bacteria that cause anthrax (Bacillus anthracis), cholera (Vibrio cholera), and tuberculosis (Mycobacterium tuberculosis).[8] We will discuss these famous microbiologists, and others, in later chapters.

As microbiology has developed, it has allowed the broader discipline of biology to grow and flourish in previously unimagined ways. Much of what we know about human cells comes from our understanding of microbes, and many of the tools we use today to study cells and their genetics derive from work with microbes.

- How did the discovery of microbes change human understanding of disease?

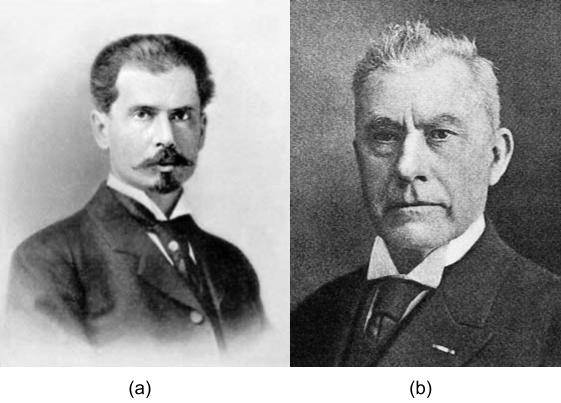

The Birth of Microbial Ecology

While the “Golden Age of Microbiology” focused on the identification of medically-relevant microbes, the same era witnessed the beginnings of the field of microbial ecology. In the late 19th century, Sergei Winogradsky (Figure 1.7) studied the sulphur-oxidizing bacterium Beggiatoa and rather than focusing his studies on pure cultures, he used lab-based ecosystems (microcosms) which became known as Winogradsky columns. These are still used today in many undergraduate microbiology laboratory courses. Through his studies, Winogradsky established the concepts of autotrophy (fixing CO2 into biomass) and lithotrophy (literally “rock eating”, meaning organisms like Beggiatoa, that obtain their energy from inorganic molecules). Around the turn of the 20th century, Martinus Beijerinck (Figure 1.7) developed enrichment culture techniques. Using a synthetic medium lacking any added nitrogen source, Beijerinck isolated the bacterium Azotobacter for the first time, exploiting its relatively rare ability to use atmospheric N2 as a sole source of nitrogen (an element in proteins and nucleic acids, among other cell structures). His technique for enriching and isolating Azotobacter is another laboratory exercise used in many undergraduate microbiology lab courses.

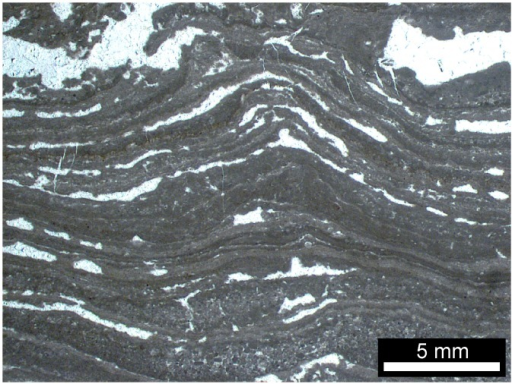

The field of microbial ecology was eclipsed for many years, as scientists raced to cure and prevent infectious diseases. However today we recognize the critical roles of the microorganisms in the health and function of the biosphere. The ubiquity, diversity and essential functions of the microbes is not surprising, given that fossil records and isotope analyses point to the bacteria and archaea as the first life forms on Earth. Some of these bacteria were photosynthetic (harvesting their energy from the sun and using some of that energy to fix carbon dioxide). In fact, the early photosynthetic bacteria (Figure 1.8) eventually (after almost 2 billion years!) produced enough oxygen to change Earth’s atmosphere from anaerobic to aerobic.[9]

The microbes, in particular the bacteria and archaea, are as important to the biosphere today as they were when they first appeared, almost 4 billion years ago. They have critical functions in every ecosystem, including as symbionts of animals, and more than 150 years after discovering their role in fermentation and disease, new roles are being continuously discovered. In fact, the field of microbial ecology is advancing dramatically, to a certain degree driven by our changing climate and the unknown impacts of man’s activities.

- What is the relevance of the microbes to primordial Earth?

To learn more about the Winogradsky column, watch this animation . You can read this article to learn about recent discoveries from northern Quebec that was reported to represent the oldest fossil evidence of life on Earth.

MICRO CONNECTIONS: Microbiology Toolbox

Because individual microbes are generally too small to be seen with the naked eye, the science of microbiology is dependent on technology that can artificially enhance the capacity of our natural senses of perception. Early microbiologists like Pasteur and Koch had fewer tools at their disposal than are found in modern laboratories, making their discoveries and innovations that much more impressive. Later chapters of this text will explore many applications of technology in depth, but for now, here is a brief overview of some of the fundamental tools of the microbiology lab.

- Microscopes produce magnified images of microorganisms, human cells and tissues, and many other types of specimens too small to be observed with the naked eye.

- Stains and dyes are used to add colour to microbes so they can be better observed under a microscope. Some dyes can be used on living microbes, whereas others require that the specimens be fixed with chemicals or heat before staining. Some stains only work on certain types of microbes because of differences in their cellular chemical composition.

- Growth media are used to grow microorganisms in a lab setting. Some media are liquids; others are more solid or gel-like. A growth medium provides nutrients, including water, various salts, a source of carbon (like glucose), and a source of nitrogen and amino acids (like yeast extract) so microorganisms can grow and reproduce. Ingredients in a growth medium can be modified to grow unique types of microorganisms.

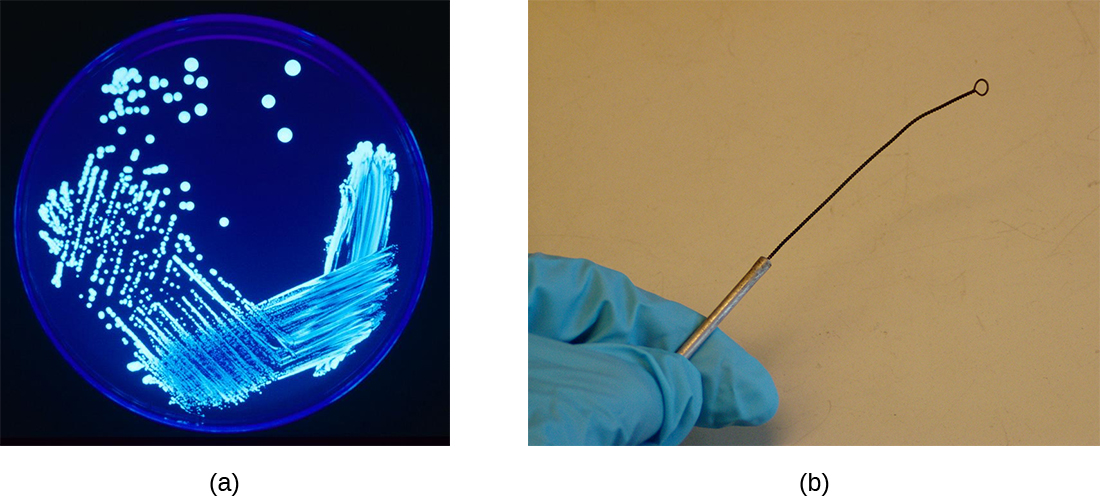

- A Petri dish is a flat-lidded dish that is typically 10–11 centimetres (cm) in diameter and 1–1.5 cm high. Petri dishes made out of either plastic or glass are used to hold growth media (Figure 1.9).

- Test tubes are cylindrical plastic or glass tubes with rounded bottoms and open tops. They can be used to grow microbes in broth, or semisolid or solid growth media.

- A Bunsen burner is a metal apparatus that creates a flame that can be used to sterilize pieces of equipment. A rubber tube carries gas (fuel) to the burner. In many labs, Bunsen burners are being phased out in favour of infrared microincinerators, which serve a similar purpose without the safety risks of an open flame.

- An inoculation loop is a handheld tool that ends in a small wire loop (Figure 1.9). The loop can be used to streak microorganisms on agar in a Petri dish or to transfer them from one test tube to another. Before each use, the inoculation loop must be sterilized so cultures do not become contaminated.

Key Takeaways

- Microorganisms (or microbes) are living organisms that are generally too small to be seen without a microscope.

- Throughout history, humans have used microbes to make fermented foods such as beer, bread, cheese, and wine.

- Long before the invention of the microscope, some people theorized that infection and disease were spread by living things that were too small to be seen. They also correctly intuited certain principles regarding the spread of disease and immunity.

- Antonie van Leeuwenhoek, using a microscope, was the first to actually observe and describe, in 1675.

- During the Golden Age of Microbiology (1857–1914), microbiologists, including Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch, discovered many new connections between the fields of microbiology and medicine.

- Sergei Winogradsky and Martinus Beijerinck are the fathers of microbial ecology, discovering lithotrophy, the role of the bacteria and archaea as primary producers and as nitrogen-fixers

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- What did Thucydides learn by observing the Athenian plague?

- Why was the invention of the microscope important for microbiology?

- What are some ways people use microbes?

Critical Thinking

- Explain how the discovery of fermented foods likely benefited our ancestors.

- What evidence would you use to support this statement: Ancient people thought that disease was transmitted by things they could not see.

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_01_01_lumbar

- OSC_Microbio_01_01_ferment

- OSC_Microbio_01_01_cloaca

- Web

- Web

- Winogradsky & Beijerinck

- 3.4 Ga stromatolite

- microbiology sign © Nick Youngson

- Web

- Rebecca Buxton. “Examination of Gram Stains of Spinal Fluid—Bacterial Meningitis.” American Society for Microbiology. 2007. http://www.microbelibrary.org/library/gram-stain/3065-examination-of-gram-stains-of-spinal-fluid-bacterial-meningitisAccessed May 12, 2019 ↵

- P.E. McGovern et al. “Fermented Beverages of Pre- and Proto-Historic China.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1 no. 51 (2004):17593–17598. doi:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. ↵

- A. Keller et al. “New Insights into the Tyrolean Iceman's Origin and Phenotype as Inferred by Whole-Genome Sequencing.” Nature Communications, 3 (2012): 698. doi:10.1038/ncomms1701. ↵

- L. Capasso. “5300 Years Ago, the Ice Man Used Natural Laxatives and Antibiotics.” The Lancet, 352 (1998) 9143: 1864. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(05)79939-6. ↵

- G. Pappas et al. “Insights Into Infectious Disease in the Era of Hippocrates.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases 12 (2008) 4:347–350. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2007.11.003. ↵

- Thucydides. The History of the Peloponnesian War. The Second Book. 431 BC. Translated by Richard Crawley. http://classics.mit.edu/Thucydides/pelopwar.2.second.html. ↵

- Plinio Prioreschi. A History of Medicine: Roman Medicine. Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellen Press, 1998: p. 215. ↵

- S.M. Blevins and M.S. Bronze. “Robert Koch and the ‘Golden Age’ of Bacteriology.” International Journal of Infectious Diseases. 14 no. 9 (2010): e744-e751. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2009.12.003. ↵

- Duda JP, Van Kranendonk MJ, Thiel V, Ionescu D, Strauss H, Schäfer N, Reitner J. 2016. A Rare Glimpse of Paleoarchean Life: Geobiology of an Exceptionally Preserved Microbial Mat Facies from the 3.4 Ga Strelley Pool Formation, Western Australia. PLoS ONE. 11:e0147629. ↵