25. Digestive System Infections

25.5 Protozoan Infections of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Learning Objectives

- Identify the most common protozoans that can cause infections of the GI tract

- Compare the major characteristics of specific protozoan diseases affecting the GI tract

Like other microbes, protozoa are abundant in natural microbiota but can also be associated with significant illness. Gastrointestinal diseases caused by protozoa are generally associated with exposure to contaminated food and water, meaning that those without access to good sanitation are at greatest risk. Even in developed countries, infections can occur and these microbes have sometimes caused significant outbreaks from contamination of public water supplies.

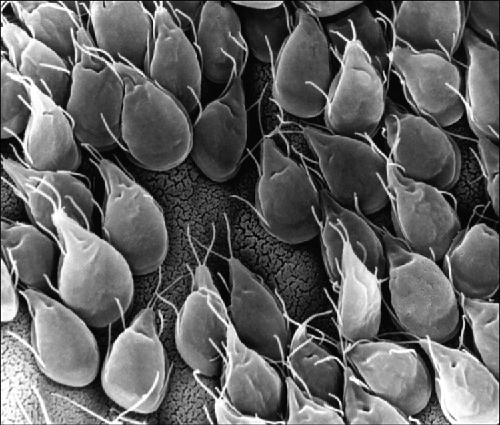

Giardiasis

Also called backpacker’s diarrhoea or beaver fever, giardiasis is a common disease in the United States caused by the flagellated protist Giardia lamblia, also known as Giardia intestinalis or Giardia duodenalis (Figure 25.24). To establish infection, G. lamblia uses a large adhesive disk to attach to the intestinal mucosa. The disk is comprised of microtubules. During adhesion, the flagella of G. lamblia move in a manner that draws fluid out from under the disk, resulting in an area of lower pressure that promotes its adhesion to the intestinal epithelial cells. Due to its attachment, Giardia also blocks absorption of nutrients, including fats.

Transmission occurs through contaminated food or water or directly from person to person. Children in day-care centres are at risk due to their tendency to put items into their mouths that may be contaminated. Large outbreaks may occur if a public water supply becomes contaminated. Giardia have a resistant cyst stage in their life cycle that is able to survive cold temperatures and the chlorination treatment typically used for drinking water in municipal reservoirs. As a result, municipal water must be filtered to trap and remove these cysts. Once consumed by the host, Giardia develops into the active tropozoite.

Infected individuals may be asymptomatic or have gastrointestinal signs and symptoms, sometimes accompanied by weight loss. Common symptoms, which appear one to three weeks after exposure, include diarrhoea, nausea, stomach cramps, gas, greasy stool (because fat absorption is being blocked), and possible dehydration. The parasite remains in the colon and does not cause systemic infection. Signs and symptoms generally clear within two to six weeks. Chronic infections may develop and are often resistant to treatment. These are associated with weight loss, episodic diarrhoea, and malabsorption syndrome due to the blocked nutrient absorption.

Diagnosis may be made using observation under the microscope. A stool ova and parasite (O&P) exam involves direct examination of a stool sample for the presence of cysts and trophozoites; it can be used to distinguish common parasitic intestinal infections. ELISA and other immunoassay tests, including commercial direct fluorescence antibody kits, are also used. The most common treatments use metronidazole as the first-line choice, followed by tinidazole. If the infection becomes chronic, the parasites may become resistant to medications.

Cryptosporidiosis

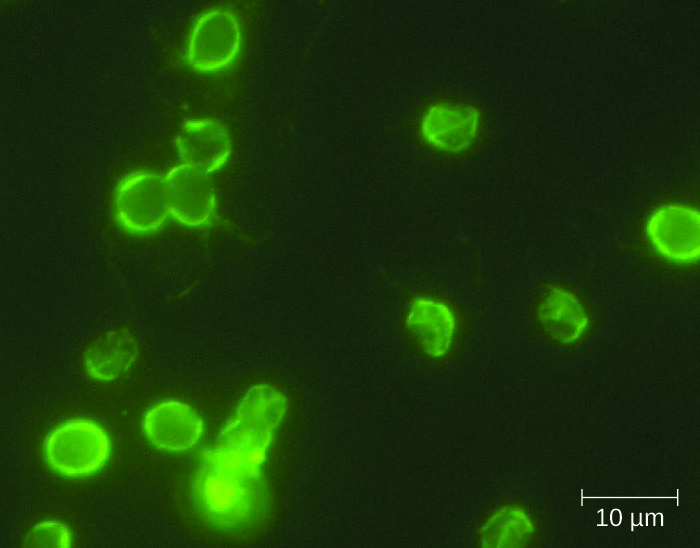

Another protozoan intestinal illness is cryptosporidiosis, which is usually caused by Cryptosporidium parvum or C. hominis. (Figure 25.26) These pathogens are commonly found in animals and can be spread in faeces from mice, birds, and farm animals. Contaminated water and food are most commonly responsible for transmission. The protozoan can also be transmitted through human contact with infected animals or their faeces.

In the United States, outbreaks of cryptosporidiosis generally occur through contamination of the public water supply or contaminated water at water parks, swimming pools, and day-care centres. The risk is greatest in areas with poor sanitation, making the disease more common in developing countries.

Signs and symptoms include watery diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, cramps, fever, dehydration, and weight loss. The illness is generally self-limiting within a month. However, immunocompromised patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS, are at particular risk of severe illness or death.

Diagnosis involves direct examination of stool samples, often over multiple days. As with giardiasis, a stool O&P exam may be helpful. Acid fast staining is often used. Enzyme immunoassays and molecular analysis (PCR) are available.

The first line of treatment is typically oral rehydration therapy. Medications are sometimes used to treat the diarrhoea. The broad-range anti-parasitic drug nitazoxanide can be used to treat cryptosporidiosis. Other anti-parasitic drugs that can be used include azithromycin and paromomycin.

Amoebiasis (Amebiasis)

The protozoan parasite Entamoeba histolytica causes amoebiasis, which is known as amoebic dysentery in severe cases. E. histolytica is generally transmitted through water or food that has faecal contamination. The disease is most widespread in the developing world and is one of the leading causes of mortality from parasitic disease worldwide. Disease can be caused by as few as 10 cysts being transmitted.

Signs and symptoms range from nonexistent to mild diarrhoea to severe amoebic dysentery. Severe infection causes the abdomen to become distended and may be associated with fever. The parasite may live in the colon without causing signs or symptoms or may invade the mucosa to cause colitis. In some cases, the disease spreads to the spleen, brain, genitourinary tract, or lungs. In particular, it may spread to the liver and cause an abscess. When a liver abscess develops, fever, nausea, liver tenderness, weight loss, and pain in the right abdominal quadrant may occur. Chronic infection may occur and is associated with intermittent diarrhoea, mucus, pain, flatulence, and weight loss.

Direct examination of faecal specimens may be used for diagnosis. As with cryptosporidiosis, samples are often examined on multiple days. A stool O&P exam of faecal or biopsy specimens may be helpful. Immunoassay, serology, biopsy, molecular, and antibody detection tests are available. Enzyme immunoassay may not distinguish current from past illness. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) can be used to detect any liver abscesses. The first line of treatment is metronidazole or tinidazole, followed by diloxanide furoate, iodoquinol, or paromomycin to eliminate the cysts that remain.

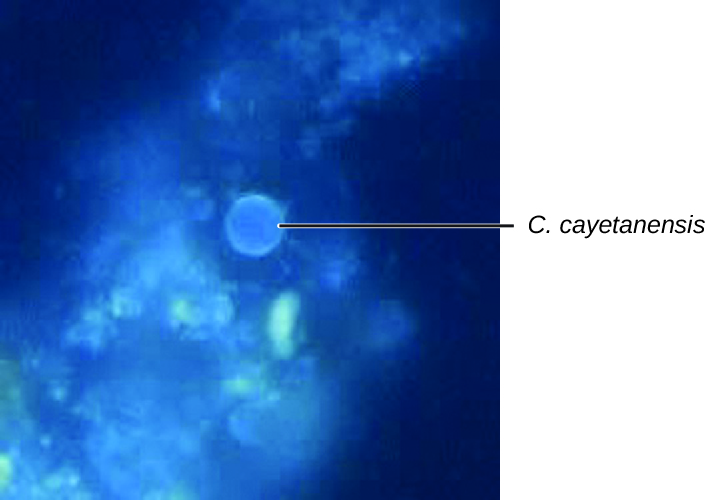

Cyclosporiasis

The intestinal disease cyclosporiasis is caused by the protozoan Cyclospora cayetanensis. It is endemic to tropical and subtropical regions and therefore uncommon in the United States, although there have been outbreaks associated with contaminated produce imported from regions where the protozoan is more common.

This protist is transmitted through contaminated food and water and reaches the lining of the small intestine, where it causes infection. Signs and symptoms begin within seven to ten days after ingestion. Based on limited data, it appears to be seasonal in ways that differ regionally and that are poorly understood.[1]

Some individuals do not develop signs or symptoms. Those who do may exhibit explosive and watery diarrhoea, fever, nausea, vomiting, cramps, loss of appetite, fatigue, and bloating. These symptoms may last for months without treatment. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is the recommended treatment.

Microscopic examination is used for diagnosis. A stool O&P examination may be helpful. The oocysts have a distinctive blue halo when viewed using ultraviolet fluorescence microscopy (Figure 25.27).

- Which protozoan GI infections are common in the United States?

CLINICAL FOCUS: Resolution

Carli’s doctor explained that she had bacterial gastroenteritis caused by Salmonella bacteria. The source of these bacteria was likely the undercooked egg. Had the egg been fully cooked, the high temperature would have been sufficient to kill any Salmonella in or on the egg. In this case, enough bacteria survived to cause an infection once the egg was eaten.

Carli’s signs and symptoms continued to worsen. Her fever became higher, her vomiting and diarrhea continued, and she began to become dehydrated. She felt thirsty all the time and had continual abdominal cramps. Carli’s doctor treated her with intravenous fluids to help with her dehydration, but did not prescribe antibiotics. Carli’s parents were confused because they thought a bacterial infection should always be treated with antibiotics.

The doctor explained that the worst medical problem for Carli was dehydration. Except in the most vulnerable and sick patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS, antibiotics do not reduce recovery time or improve outcomes in Salmonella infections. In fact, antibiotics can actually delay the natural excretion of bacteria from the body. Rehydration therapy replenishes lost fluids, diminishing the effects of dehydration and improving the patient’s condition while the infection resolves.

After two days of rehydration therapy, Carli’s signs and symptoms began to fade. She was still somewhat thirsty, but the amount of urine she passed became larger and the color lighter. She stopped vomiting. Her fever was gone, and so was the diarrhea. At that point, stool analysis found very few Salmonella bacteria. In one week, Carli was discharged as fully recovered.

Go back to the previous Clinical Focus box.

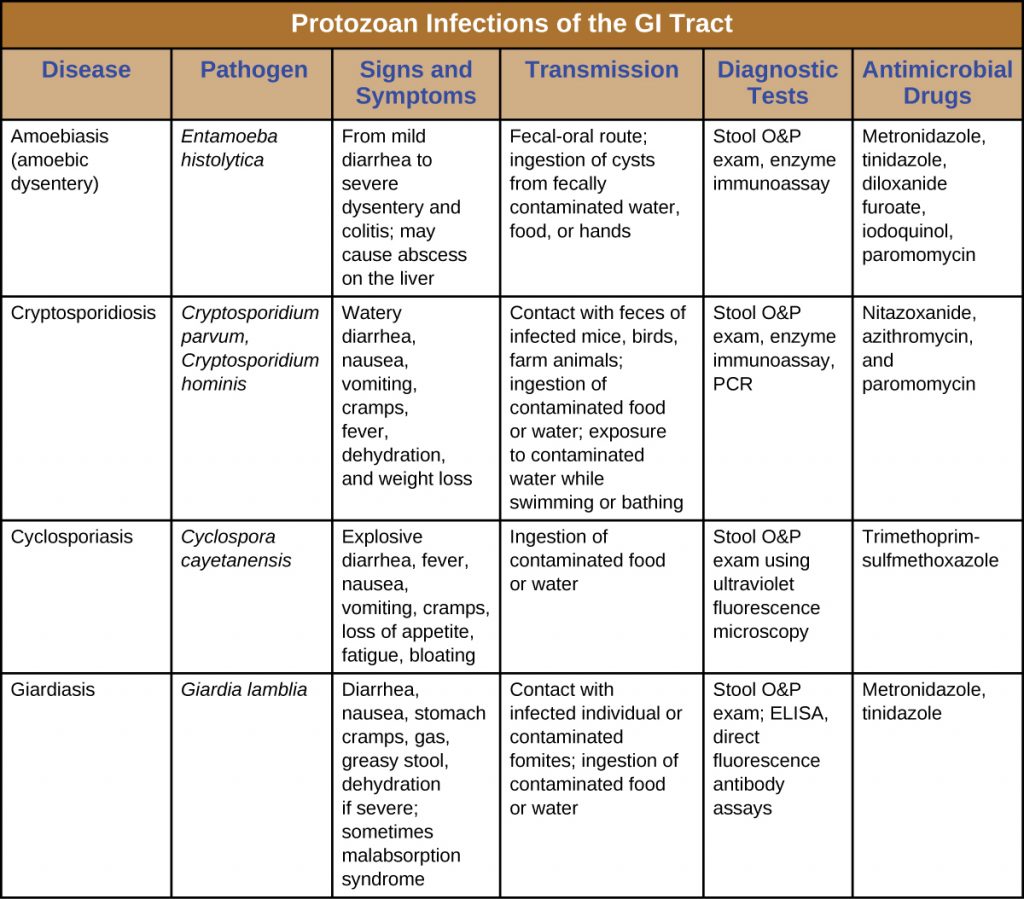

DISEASE PROFILE: PROTOZOAN Gastrointestinal Infections

Protozoan GI infections are generally transmitted through contaminated food or water, triggering diarrhoea and vomiting that can lead to dehydration. Rehydration therapy is an important aspect of treatment, but most protozoan GI infections can also be treated with drugs that target protozoans.

Table 25.4. Protozoan Infections of the GI Tract

Key Takeaways

- Giardiasis, cryptosporidiosis, amoebiasis, and cyclosporiasis are intestinal infections caused by protozoans.

- Protozoan intestinal infections are commonly transmitted through contaminated food and water.

- Treatment varies depending on the causative agent, so proper diagnosis is important.

- Microscopic examination of stool or biopsy specimens is often used in diagnosis, in combination with other approaches.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- What is an O&P exam?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_giardia

- OSC_Microbio_24_05_Cryptospor

- OSC_Microbio_24_05_Cyclospor

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Cyclosporiasis FAQs for Health Professionals.” Updated May 14, 2019. http://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/health_professionals/hp-faqs.html. ↵