8. Microbial Catabolism

8.1 Energy, Redox Reactions, and Enzymes

Learning Objectives

- Define and describe metabolism

- Describe the relationship between anabolism, catabolism and chemical energy

- Describe the connection between the laws of thermodynamics,

and metabolic reactions

and metabolic reactions - Compare and contrast autotrophs and heterotrophs

- Describe the importance of oxidation-reduction reactions in metabolism

- Describe why ATP, FAD, NAD+, and NADP+ are important in a cell

- Identify the structure and structural components of an enzyme and how enzymes increase reaction rates

- Describe the differences between competitive and noncompetitive enzyme inhibitors

CLINICAL FOCUS: Part 1

Hannah is a 15-month-old girl from Washington state. She is spending the summer in Gambia, where her parents are working for a nongovernmental organization. About 3 weeks after her arrival in Gambia, Hannah’s appetite began to diminish and her parents noticed that she seemed unusually sluggish, fatigued, and confused. She also seemed very irritable when she was outdoors, especially during the day. When she began vomiting, her parents figured she had caught a 24-hour virus, but when her symptoms persisted, they took her to a clinic. The local physician noticed that Hannah’s reflexes seemed abnormally slow, and when he examined her eyes with a light, she seemed unusually light sensitive. She also seemed to be experiencing a stiff neck.

- What are some possible causes of Hannah’s symptoms?

Jump to the next Clinical Focus box.

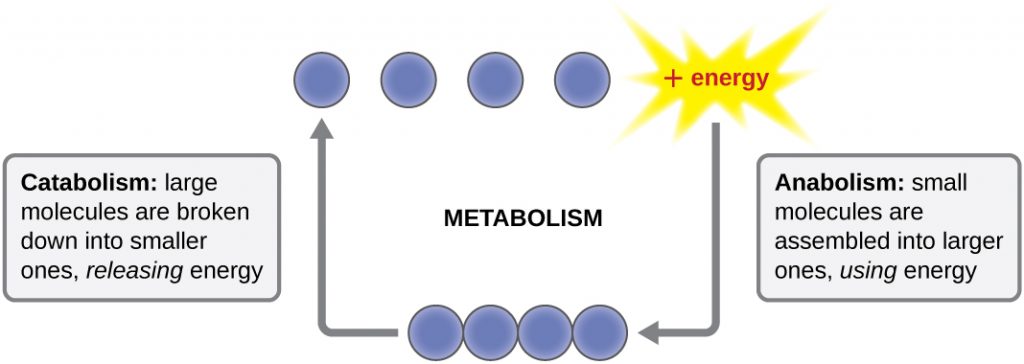

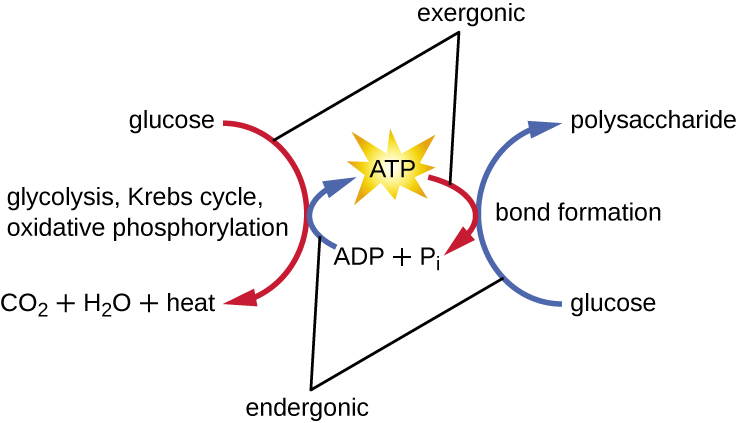

The term used to describe all of the chemical reactions inside a cell is metabolism (Figure 8.2). Cellular processes such as the building or breaking down of complex molecules occur through series of stepwise, interconnected chemical reactions called metabolic pathways. Reactions that are spontaneous and release energy are exergonic reactions, whereas endergonic reactions require energy to proceed. The term anabolism refers to those endergonic metabolic pathways involved in biosynthesis, converting simple molecular building blocks into more complex molecules, and fuelled by the use of cellular energy. Conversely, the term catabolism refers to exergonic pathways that break down complex molecules into simpler ones. Molecular energy stored in the bonds of complex molecules is released in catabolic pathways and harvested in such a way that it can be used to produce high-energy molecules, which are used to drive anabolic pathways. Thus, in terms of energy and molecules, cells are continually balancing catabolism with anabolism.

Free Energy

The very existence of living cells relies heavily on chemical energy – the potential energy in bonds. Breaking the molecular bonds within fuel molecules brings about the energy’s release. But how do we quantify and express the chemical reactions with the associated energy? How can we compare the energy liberated from one reaction to that from another reaction? We use a measurement of free energy known as Gibbs free energy (abbreviated with the letter G) after Josiah Willard Gibbs, the scientist who developed the measurement. Recall that according to the second law of thermodynamics, all energy transfers involve losing some energy in an unusable form such as heat, resulting in entropy. Gibbs free energy specifically refers to the energy that takes place with a chemical reaction that is available after we account for entropy. In other words, Gibbs free energy is usable energy, or energy that is available to do work.

Every chemical reaction involves a change in free energy, called delta G (∆G). We can calculate the change in free energy for any system that undergoes such a change, such as a chemical reaction. To calculate ∆G, subtract the amount of energy lost to entropy (denoted as ∆S) from the system’s total energy change. Scientists call this total energy change in the system enthalpy and we denote it as ∆H. The formula for calculating ∆G is as follows, where the symbol T refers to absolute temperature in Kelvin (degrees Celsius + 273):

![]()

We generally express a chemical reaction’s standard free energy change as an amount of energy per mole of the reaction product (either in kilojoules or kilocalories, kJ/mol or kcal/mol; 1 kJ = 0.239 kcal) under standard pH, temperature, and pressure conditions: under these standard conditions, we use the value ![]() . We generally calculate standard pH, temperature, and pressure conditions at pH 7.0 in biological systems, 25 degrees Celsius, and 100 kilopascals (1 atm pressure), respectively. It is important to note, however, that cells are not closed systems, and that cellular conditions vary considerably from these standard conditions, and so the standard free energy change

. We generally calculate standard pH, temperature, and pressure conditions at pH 7.0 in biological systems, 25 degrees Celsius, and 100 kilopascals (1 atm pressure), respectively. It is important to note, however, that cells are not closed systems, and that cellular conditions vary considerably from these standard conditions, and so the standard free energy change ![]() is often not the same as the actual

is often not the same as the actual ![]() for biological reactions inside the cell.

for biological reactions inside the cell.

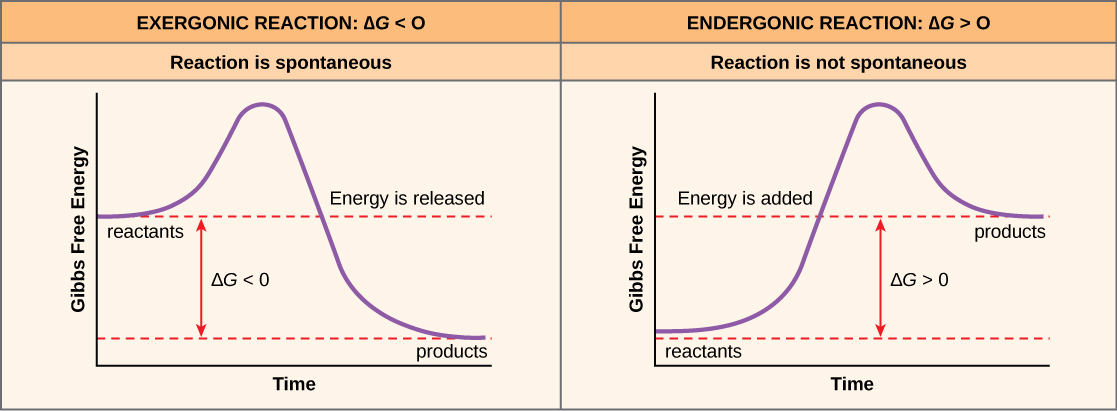

Endergonic Reactions and Exergonic Reactions

If energy is released during a chemical reaction, then the resulting value from the above equation will be a negative number. In other words, reactions that release energy have a ![]() . A negative

. A negative ![]() also means that the reaction’s products have less free energy than the reactants, because they lost some free energy during the reaction. Reactions that have a negative

also means that the reaction’s products have less free energy than the reactants, because they lost some free energy during the reaction. Reactions that have a negative ![]() and consequently release free energy are exergonic reactions. We also refer to these reactions as spontaneous reactions, because they can occur without adding energy into the system. Understanding which chemical reactions are spontaneous and release free energy is extremely useful for biologists, because these reactions can be harnessed to perform work inside the cell. Note that contrary to the everyday use of the term, a spontaneous reaction is not one that occurs suddenly or quickly. Rusting iron is an example of a spontaneous reaction that occurs slowly, little by little, over time. For biological systems, enzymes help speed up spontaneous reactions. If a chemical reaction requires an input of energy, then the

and consequently release free energy are exergonic reactions. We also refer to these reactions as spontaneous reactions, because they can occur without adding energy into the system. Understanding which chemical reactions are spontaneous and release free energy is extremely useful for biologists, because these reactions can be harnessed to perform work inside the cell. Note that contrary to the everyday use of the term, a spontaneous reaction is not one that occurs suddenly or quickly. Rusting iron is an example of a spontaneous reaction that occurs slowly, little by little, over time. For biological systems, enzymes help speed up spontaneous reactions. If a chemical reaction requires an input of energy, then the![]() for that reaction will be positive. In this case, the products have more free energy than the reactants. These products are essentially energy-storing molecules, and their formation is through endergonic reactions. An endergonic reaction is not spontaneous and will not take place without an input of free energy.

for that reaction will be positive. In this case, the products have more free energy than the reactants. These products are essentially energy-storing molecules, and their formation is through endergonic reactions. An endergonic reaction is not spontaneous and will not take place without an input of free energy.

An important concept in studying metabolism and energy is that of chemical equilibrium. Most chemical reactions are reversible. They can proceed in both directions, releasing energy into their environment in one direction, and absorbing it from the environment in the other direction (Figure 8.3). The same is true for the chemical reactions involved in cellular metabolism. Reactants within a closed system will undergo chemical reactions in both directions until they reach a state of equilibrium, which is one of the lowest possible free energy and a state of maximal entropy. To push the reactants and products away from a state of equilibrium requires energy. Either reactants or products must be added, removed, or changed. If a cell were a closed system, its chemical reactions would reach equilibrium, and it would die because there would be insufficient free energy left to perform the necessary work to maintain life. In a living cell, chemical reactions are constantly moving towards equilibrium, but never reach it. This is because a living cell is an open system. Materials pass in and out and the cell recycles the products of certain chemical reactions into other reactions. In this way, living organisms are in a constant energy-requiring, uphill battle against equilibrium and entropy.

Classification by Carbon and Energy Source

The constant supply of energy required for life on Earth to continue comes primarily from sunlight, which provides the energy for photosynthetic organisms to build biomass. Organisms can be identified according to the source of carbon they use for metabolism as well as their energy source. The prefixes auto- (“self”) and hetero- (“other”) refer to the origins of the carbon sources various organisms can use. Organisms that convert inorganic carbon dioxide (CO2) into organic carbon compounds are autotrophs. Plants and cyanobacteria are well-known examples of autotrophs. Conversely, heterotrophs rely on more complex organic carbon compounds as nutrients; these are provided to them initially by autotrophs. Many organisms, ranging from humans to many prokaryotes, including the well-studied Escherichia coli, are heterotrophic.

Organisms can also be identified by the energy source they use. All energy is derived from the transfer of electrons, but the source of electrons differs between various types of organisms. The prefixes photo- (“light”) and chemo- (“chemical”) refer to the energy sources that various organisms use. Those that get their energy for electron transfer from light are phototrophs, whereas chemotrophs obtain energy for electron transfer by breaking chemical bonds. There are two types of chemotrophs: organotrophs and lithotrophs. Organotrophs, including humans, fungi, and many prokaryotes, are chemotrophs that obtain energy from organic compounds. Lithotrophs (“litho” means “rock”) are chemotrophs that get energy from inorganic compounds, including hydrogen sulphide (H2S) and reduced iron. Lithotrophy is unique to the bacterial and archaeal domains.

The strategies used to obtain both carbon and energy can be combined for the classification of organisms according to nutritional type. Most organisms are chemoheterotrophs because they use organic molecules as both their electron and carbon sources. Table 8.1 summarizes this and the other classifications. Chemoautotrophs are all lithotrophs, obtaining their carbon from CO2 (i.e.CO2 fixation). Photoauthotrophs are the photosynthetic organisms, using the energy from phototrophy, to synthesize biomass.

Table 8.1 – Classifications of Organisms by Energy and Carbon Source

| Classifications of Organisms by Energy and Carbon Source | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classifications | Energy Source | Carbon Source | Examples | |

| Chemotrophs | Chemoautotrophs | Chemical | Inorganic | Hydrogen-, sulphur-, iron-, nitrogen-, and carbon monoxide-oxidizing bacteria and archaea |

| Chemoheterotrophs | Chemical | Organic compounds | All animals, most fungi, protozoa, many species of bacteria and archaea | |

| Phototrophs | Photoautotrophs | Light | Inorganic | All plants, algae, cyanobacteria, and green and purple sulphur bacteria |

| Photoheterotrophs | Light | Organic compounds | Green and purple nonsulphur bacteria, heliobacteria, halophilic archaea | |

- Explain the difference between catabolism and anabolism.

- Explain the difference between autotrophs and heterotrophs.

Oxidation and Reduction in Metabolism

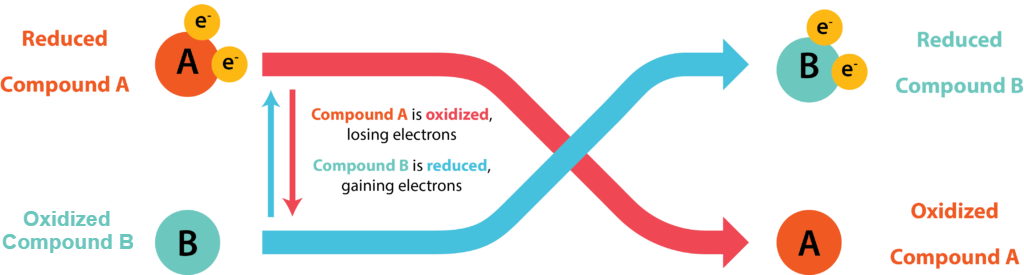

The transfer of electrons between molecules is important because most of the energy stored in atoms and used to fuel cell functions is in the form of high-energy electrons. The transfer of energy in the form of electrons allows the cell to transfer and use energy incrementally; that is, in small packages rather than a single, destructive burst. Reactions that remove electrons from donor molecules, leaving them oxidized, are oxidation reactions; those that add electrons to acceptor molecules, leaving them reduced, are reduction reactions. Because electrons can move from one molecule to another, oxidation and reduction occur in tandem. These pairs of reactions are called oxidation-reduction reactions, or redox reactions. The general process is depicted in Figure 8.4.

A substance can be either an electron donor or an electron acceptor, dependent upon the other substances in the reaction. A redox couple represents both forms of a substance in a half reaction, with the oxidized form (the electron acceptor) always placed on the left and the reduced form (the electron donor) on the right. An example would be ![]() O2 / H2O, where H2O could serve as an electron donor and O2 could serve as an electron acceptor. Each half reaction is given a standard reduction potential (

O2 / H2O, where H2O could serve as an electron donor and O2 could serve as an electron acceptor. Each half reaction is given a standard reduction potential (![]() ) in volts or millivolts, which is a measurement of the tendency of the donor in the reaction to give up electrons. A substance with greater tendency to donate electrons in the reduced form has a more negative

) in volts or millivolts, which is a measurement of the tendency of the donor in the reaction to give up electrons. A substance with greater tendency to donate electrons in the reduced form has a more negative ![]() , while a substance with a weak tendency to donate electrons in the reduced form has a less negative or even positive

, while a substance with a weak tendency to donate electrons in the reduced form has a less negative or even positive ![]() . A substance with a negative

. A substance with a negative ![]() makes a very good electron donor, in the reduced form.

makes a very good electron donor, in the reduced form.

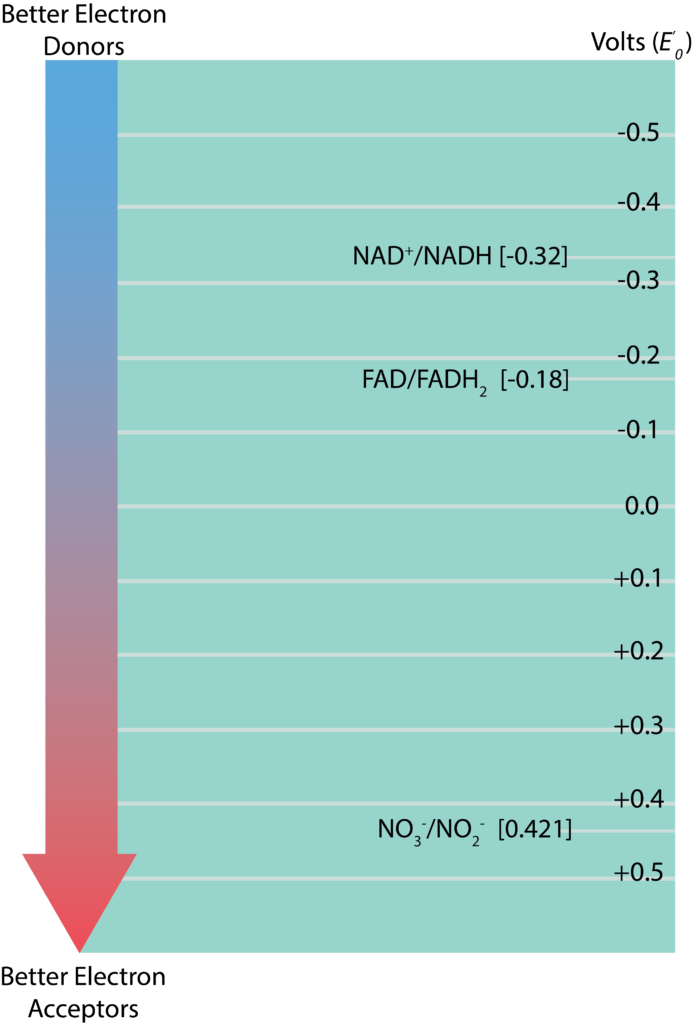

Redox Tower

The information regarding standard reduction potentials for various redox couples is displayed in the form of a redox tower (Figure 8.5), which lists the couples in a vertical form based on their ![]() . Redox couples with the most negative

. Redox couples with the most negative ![]() on listed at the top while those with the most positive

on listed at the top while those with the most positive ![]() are listed on the bottom. The reduced substance with the greatest tendency to donate electrons would be found at the top of the tower on the right, while the oxidized substance with the greatest tendency to accept electrons would be found at the bottom of the tower on the left. Redox couples in the middle can serve as either electron donors or acceptors, depending upon what substance they partner with for a reaction. The difference between reduction potentials of a donor and an acceptor (

are listed on the bottom. The reduced substance with the greatest tendency to donate electrons would be found at the top of the tower on the right, while the oxidized substance with the greatest tendency to accept electrons would be found at the bottom of the tower on the left. Redox couples in the middle can serve as either electron donors or acceptors, depending upon what substance they partner with for a reaction. The difference between reduction potentials of a donor and an acceptor (![]() ) is measured as acceptor

) is measured as acceptor ![]() minus donor

minus donor ![]() . The larger the value for

. The larger the value for ![]() , the more potential energy for a cell. Larger values are derived when there is the biggest distance between the donor and the acceptor (or a bigger fall down the tower). A simplified electron tower is depicted in the figure below. The two couples towards the top are typical electron carriers and are described in the next section.

, the more potential energy for a cell. Larger values are derived when there is the biggest distance between the donor and the acceptor (or a bigger fall down the tower). A simplified electron tower is depicted in the figure below. The two couples towards the top are typical electron carriers and are described in the next section.

Energy Carriers: NADH, NADPH, FADH2, and ATP

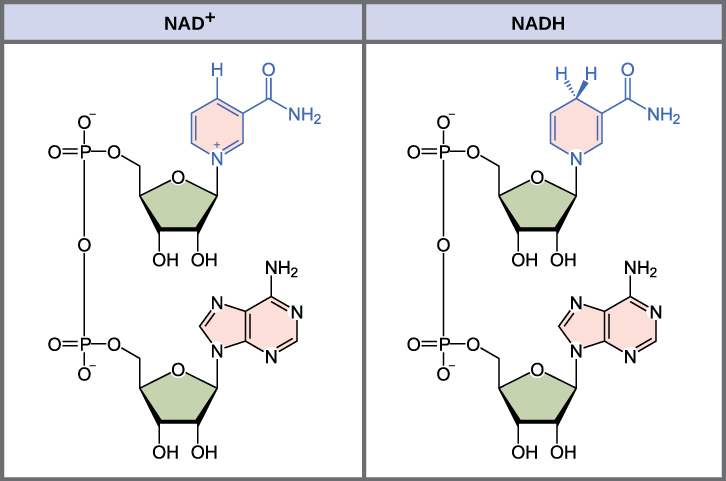

The energy released from the breakdown of the chemical bonds within nutrients can be stored either through the reduction of electron carriers or in the bonds of adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In living systems, a small class of compounds functions as mobile electron carriers, molecules that bind to and shuttle high-energy electrons between compounds in pathways. The principal electron carriers we will consider originate from the B vitamin group and are derivatives of nucleotides; they are nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide, nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphate, and flavin adenine dinucleotide (Figure 8.6). These compounds can be easily reduced or oxidized. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+/NADH) is the most common mobile electron carrier used in catabolism. NAD+ is the oxidized form of the molecule; NADH is the reduced form of the molecule. Nicotine adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP+), the oxidized form of an NAD+ variant that contains an extra phosphate group, is another important electron carrier; it forms NADPH when reduced. The oxidized form of flavin adenine dinucleotide is FAD, and its reduced form is FADH2. Both NAD+/NADH and FAD/FADH2 are extensively used in energy extraction from sugars during catabolism in chemoheterotrophs, whereas NADP+/NADPH plays an important role in anabolic reactions and photosynthesis. Collectively, FADH2, NADH, and NADPH are often referred to as having reducing power due to their ability to donate electrons to various chemical reactions.

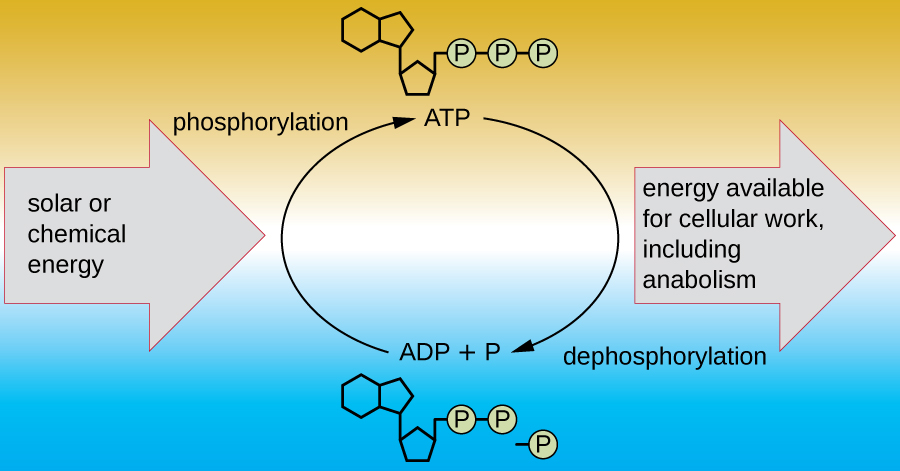

A living cell must be able to handle the energy released during catabolism in a way that enables the cell to store energy safely and release it for use only as needed. Living cells accomplish this by using the compound adenosine triphosphate (ATP). ATP is often called the “energy currency” of the cell, and, like currency, this versatile compound can be used to fill any energy need of the cell. At the heart of ATP is a molecule of adenosine monophosphate (AMP), which is composed of an adenine molecule bonded to a ribose molecule and a single phosphate group. Ribose is a five-carbon sugar found in RNA, and AMP is one of the nucleotides in RNA. The addition of a second phosphate group to this core molecule results in the formation of adenosine diphosphate (ADP); the addition of a third phosphate group forms ATP (Figure 8.7). Adding a phosphate group to a molecule, a process called phosphorylation, requires energy. Phosphate groups are negatively charged and thus repel one another when they are arranged in series, as they are in ADP and ATP. This repulsion makes the ADP and ATP molecules inherently unstable. Thus, the bonds between phosphate groups (one in ADP and two in ATP) are called high-energy phosphate bonds. When these high-energy bonds are broken to release one phosphate (called inorganic phosphate [Pi]) or two connected phosphate groups (called pyrophosphate [PPi]) from ATP through a process called dephosphorylation, energy is released to drive endergonic reactions (Figure 8.8). This is an example of energy coupling, and is the basis for cellular metabolism: catabolic reactions produce the energy required to drive anabolic reactions.

- What is the function of an electron carrier?

- What is a redox tower and what does the standard reduction potential represent?

Enzyme Structure and Function

A substance that helps speed up a chemical reaction is a catalyst. Catalysts are not used or changed during chemical reactions and, therefore, are reusable. Whereas inorganic molecules may serve as catalysts for a wide range of chemical reactions, proteins called enzymes serve as catalysts for biochemical reactions inside cells. Enzymes thus play an important role in controlling cellular metabolism.

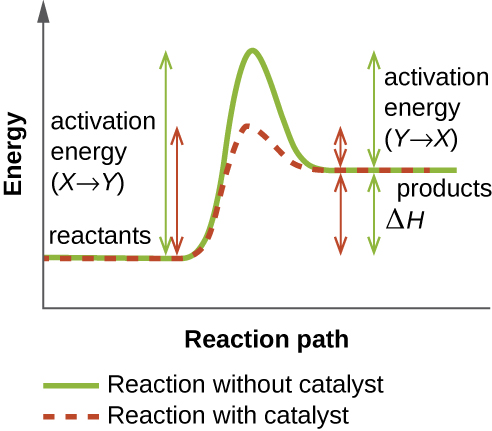

An enzyme functions by lowering the activation energy of a chemical reaction inside the cell. Activation energy is the energy needed to form or break chemical bonds and convert reactants to products (Figure 8.9). Enzymes lower the activation energy by binding to the reactant molecules and holding them in such a way as to speed up the reaction.

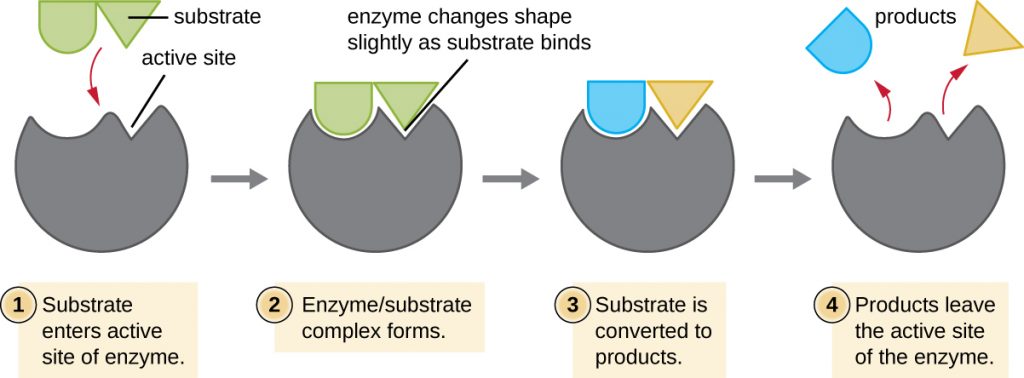

The chemical reactants to which an enzyme binds are called substrates, and the location within the enzyme where the substrate binds is called the enzyme’s active site. The characteristics of the amino acids near the active site create a very specific chemical environment within the active site that induces suitability to binding, albeit briefly, to a specific substrate (or substrates). Due to this jigsaw puzzle-like match between an enzyme and its substrates, enzymes are known for their specificity. In fact, as an enzyme binds to its substrate(s), the enzyme structure changes slightly to find the best fit between the transition state (a structural intermediate between the substrate and product) and the active site, just as a rubber glove moulds to a hand inserted into it. This active-site modification in the presence of substrate, along with the simultaneous formation of the transition state, is called induced fit (Figure 8.10). Overall, there is a specifically matched enzyme for each substrate and, thus, for each chemical reaction; however, there is some flexibility as well. Some enzymes have the ability to act on several different structurally related substrates.

Enzymes are subject to influences by local environmental conditions such as pH, substrate concentration, and temperature. Although increasing the environmental temperature generally increases reaction rates, enzyme catalyzed or otherwise, increasing or decreasing the temperature outside of an optimal range can affect chemical bonds within the active site, making them less well suited to bind substrates. High temperatures will eventually cause enzymes, like other biological molecules, to denature, losing their three-dimensional structure and function. Enzymes are also suited to function best within a certain pH range, and, as with temperature, extreme environmental pH values (acidic or basic) can cause enzymes to denature. Active-site amino-acid side chains have their own acidic or basic properties that are optimal for catalysis and, therefore, are sensitive to changes in pH.

Another factor that influences enzyme activity is substrate concentration: Enzyme activity is increased at higher concentrations of substrate until it reaches a saturation point at which the enzyme can bind no additional substrate. Overall, enzymes are optimized to work best under the environmental conditions in which the organisms that produce them live. For example, while microbes that inhabit hot springs have enzymes that work best at high temperatures, human pathogens have enzymes that work best at 37°C. Similarly, while enzymes produced by most organisms work best at a neutral pH, microbes growing in acidic environments make enzymes optimized to low pH conditions, allowing for their growth at those conditions.

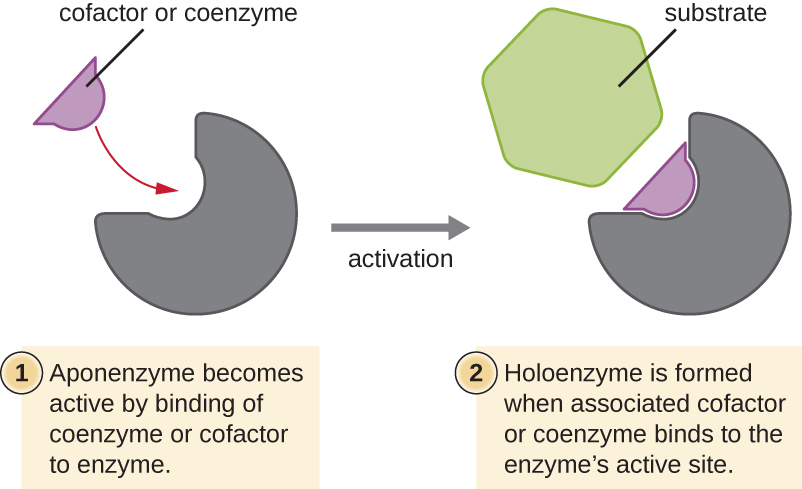

Many enzymes do not work optimally, or even at all, unless bound to other specific nonprotein helper molecules, either temporarily through ionic or hydrogen bonds or permanently through stronger covalent bonds. Binding to these molecules promotes optimal conformation and function for their respective enzymes. Two types of helper molecules are cofactors and coenzymes. Cofactors are inorganic ions such as iron (Fe2+) and magnesium (Mg2+) that help stabilize enzyme conformation and function. One example of an enzyme that requires a metal ion as a cofactor is the enzyme that builds DNA molecules, DNA polymerase, which requires a bound zinc ion (Zn2+) to function.

Coenzymes are organic helper molecules that are required for enzyme action. Like enzymes, they are not consumed and, hence, are reusable. The most common sources of coenzymes are dietary vitamins. Some vitamins are precursors to coenzymes and others act directly as coenzymes.

Some cofactors and coenzymes, like coenzyme A (CoA), often bind to the enzyme’s active site, aiding in the chemistry of the transition of a substrate to a product (Figure 8.11). In such cases, an enzyme lacking a necessary cofactor or coenzyme is called an apoenzyme and is inactive. Conversely, an enzyme with the necessary associated cofactor or coenzyme is called a holoenzyme and is active. NADH and ATP are also both examples of commonly used coenzymes that provide high-energy electrons or phosphate groups, respectively, which bind to enzymes, thereby activating them.

- What role do enzymes play in a chemical reaction?

Enzyme Inhibitors

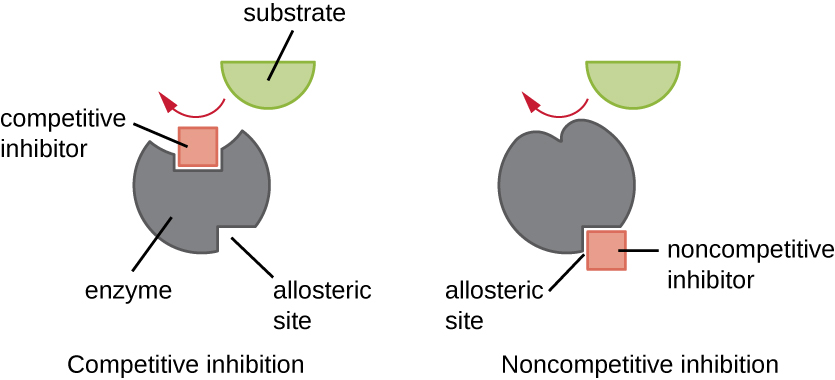

Enzymes can be regulated in ways that either promote or reduce their activity. There are many different kinds of molecules that inhibit or promote enzyme function, and various mechanisms exist for doing so (Figure 8.12). A competitive inhibitor is a molecule similar enough to a substrate that it can compete with the substrate for binding to the active site by simply blocking the substrate from binding. For a competitive inhibitor to be effective, the inhibitor concentration needs to be approximately equal to the substrate concentration. Sulfa drugs provide a good example of competitive competition. They are used to treat bacterial infections because they bind to the active site of an enzyme within the bacterial folic acid synthesis pathway. When present in a sufficient dose, a sulfa drug prevents folic acid synthesis, and bacteria are unable to grow because they cannot synthesize DNA, RNA, and proteins. Humans are unaffected because we obtain folic acid from our diets.

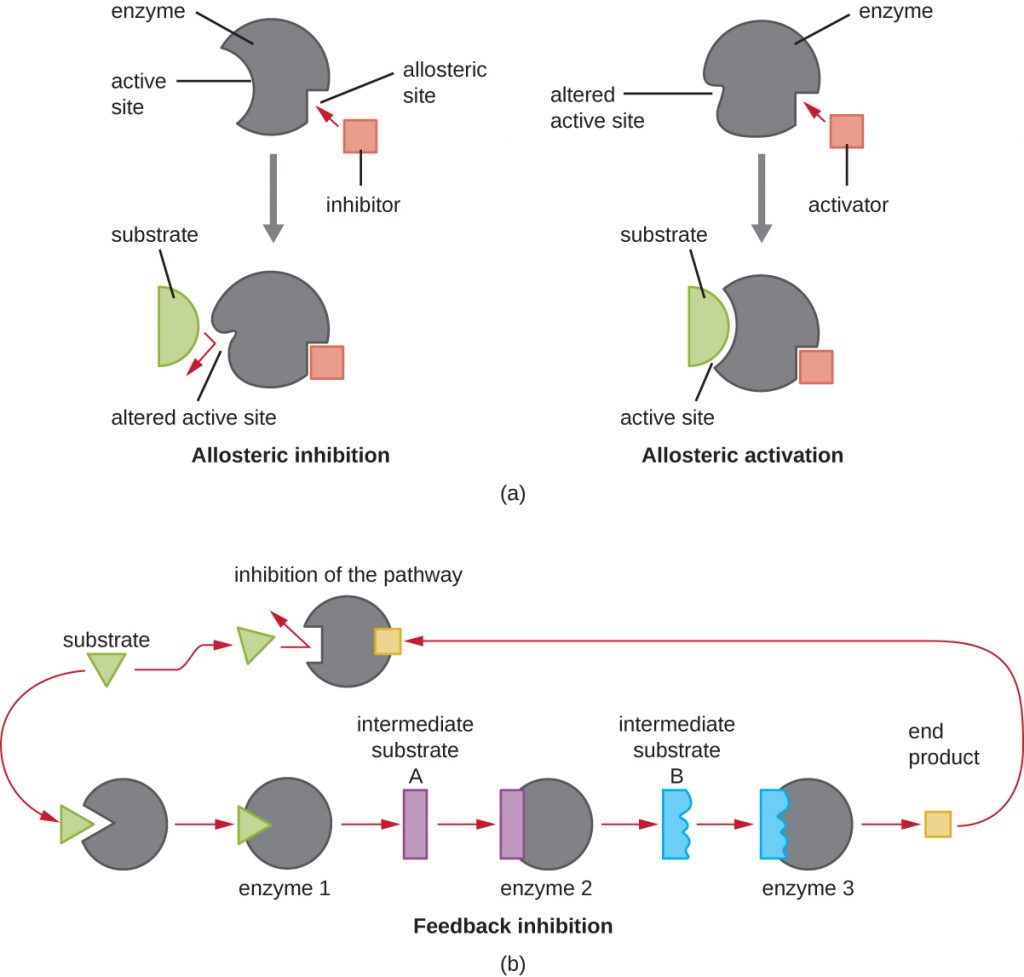

On the other hand, a noncompetitive (allosteric) inhibitor binds to the enzyme at an allosteric site, a location other than the active site, and still manages to block substrate binding to the active site by inducing a conformational change that reduces the affinity of the enzyme for its substrate (Figure 8.13). Because only one inhibitor molecule is needed per enzyme for effective inhibition, the concentration of inhibitors needed for noncompetitive inhibition is typically much lower than the substrate concentration.

In addition to allosteric inhibitors, there are allosteric activators that bind to locations on an enzyme away from the active site, inducing a conformational change that increases the affinity of the enzyme’s active site(s) for its substrate(s).

Allosteric control is an important mechanism of regulation of metabolic pathways involved in both catabolism and anabolism. In a most efficient and elegant way, cells have evolved also to use the products of their own metabolic reactions for feedback inhibition of enzyme activity. Feedback inhibition involves the use of a pathway product to regulate its own further production. The cell responds to the abundance of specific products by slowing production during anabolic or catabolic reactions (Figure 8.12).

- Explain the difference between a competitive inhibitor and a noncompetitive inhibitor.

Key Takeaways

- Metabolism includes chemical reactions that break down complex molecules (catabolism) and those that build complex molecules (anabolism).

- Living cells obey the laws of thermodynamics and require a constant source of free energy in order to reduce entropy

- This energy comes from the chemical energy of molecular bonds. The free energy that is released by breaking these bonds is given by a negative

. These are exergonic reactions and are typically associated with catabolism

. These are exergonic reactions and are typically associated with catabolism - An endergonic or energy-consuming reaction has a positive

and is typical of anabolic reactions

and is typical of anabolic reactions - Organisms may be classified according to their source of carbon. Autotrophs convert inorganic carbon dioxide into organic carbon; heterotrophs use fixed organic carbon compounds.

- Organisms may also be classified according to their energy source. Phototrophs obtain their energy from light. Chemotrophs get their energy from chemical compounds. Organotrophs use organic molecules, and lithotrophs use inorganic chemicals.

- Cellular electron carriers accept high-energy electrons from foods and later serve as electron donors in subsequent redox reactions. FAD/FADH2, NAD+/NADH, and NADP+/NADPH are important electron carriers.

- Redox couples are arranged in redox towers based on standard reduction potentials (

). By convention, the reduced form of the couple is on the right, and those with the greatest tendency as reductants, are at the top, with the most negative values.

). By convention, the reduced form of the couple is on the right, and those with the greatest tendency as reductants, are at the top, with the most negative values. - Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) serves as the energy currency of the cell, safely storing chemical energy in its two high-energy phosphate bonds for later use to drive processes requiring energy.

- Enzymes are biological catalysts that increase the rate of chemical reactions inside cells by lowering the activation energy required for the reaction to proceed.

- In nature, exergonic reactions may proceed without enzymes, but at a slow rate. Conversely, endergonic reactions require energy beyond activation energy and in cells are coupled to exergonic reactions, making the combination energetically favourable.

- Substrates bind to the enzyme’s active site. This process typically alters the structures of both the active site and the substrate, favouring transition-state formation; this is known as induced fit.

- Cofactors are inorganic ions that stabilize enzyme conformation and function. Coenzymes are organic molecules required for proper enzyme function and are often derived from vitamins. An enzyme lacking a cofactor or coenzyme is an apoenzyme; an enzyme with a bound cofactor or coenzyme is a holoenzyme.

- Competitive inhibitors regulate enzymes by binding to an enzyme’s active site, preventing substrate binding. Noncompetitive (allosteric) inhibitors bind to allosteric sites, inducing a conformational change in the enzyme that prevents it from functioning. Feedback inhibition occurs when the product of a metabolic pathway non-competitively binds to an enzyme early on in the pathway, ultimately preventing the synthesis of the product.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

True/False

Short Answer

- In cells, can an oxidation reaction happen in the absence of a reduction reaction? Explain.

- What is the function of molecules like NAD+/NADH and FAD/FADH2 in cells?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_metabolism

- Energonic and exergonic reactions

- Redox couple

- Redox tower

- NAD+ and NADH structures

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_ATP

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_EndoExo

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_Enzymes

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_InducedFit

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_ApoHolo

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_EnzInh

- OSC_Microbio_08_01_InhAct