23. Respiratory System Infections

23.4 Respiratory Mycoses

Learning Objectives

- Identify the most common fungi that can cause infections of the respiratory tract

- Compare the major characteristics of specific fungal diseases of the respiratory tract

Fungal pathogens are ubiquitous in the environment. Serological studies have demonstrated that most people have been exposed to fungal respiratory pathogens during their lives. Yet symptomatic infections by these microbes are rare in healthy individuals. This demonstrates the efficacy of the defences of our respiratory system. In this section, we will examine some of the fungi that can cause respiratory infections.

Histoplasmosis

Histoplasmosis is a fungal disease of the respiratory system and most commonly occurs in the Mississippi Valley of the United States and in parts of Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and Australia. The causative agent, Histoplasma capsulatum, is a dimorphic fungus. This microbe grows as a filamentous mould in the environment but occurs as a budding yeast during human infections. The primary reservoir for this pathogen is soil, particularly in locations rich in bat or bird faeces.

Histoplasmosis is acquired by inhaling microconidial spores in the air; this disease is not transmitted from human to human. The incidence of histoplasmosis exposure is high in endemic areas, with 60%–90% of the population having anti-Histoplasma antibodies, depending on location;[1] however, relatively few individuals exposed to the fungus actually experience symptoms. Those most likely to be affected are the very young, the elderly, and immunocompromised people.

In many ways, the course of this disease is similar to that of tuberculosis. Following inhalation, the spores enter the lungs and are phagocytized by alveolar macrophages. The fungal cells then survive and multiply within these phagocytes (see Figure 5.19). Focal infections cause the formation of granulomatous lesions, which can lead to calcifications that resemble the Ghon complexes of tuberculosis, even in asymptomatic cases. Also like tuberculosis, histoplasmosis can become chronic and reactivation can occur, along with dissemination to other areas of the body (e.g., the liver or spleen).

Signs and symptoms of pulmonary histoplasmosis include fever, headache, and weakness with some chest discomfort. The initial diagnosis is often based on chest radiographs and cultures grown on fungal selective media like Sabouraud’s dextrose agar. Direct fluorescence antibody staining and Giemsa staining can also be used to detect this pathogen. In addition, serological tests including a complement fixation assay and histoplasmin sensitivity can be used to confirm the diagnosis. In most cases, these infections are self-limiting and antifungal therapy is not required. However, in disseminated disease, the antifungal agents amphotericin B and ketoconazole are effective; itraconazole may be effective in immunocompromised patients, in whom the disease can be more serious.

- In what environments is one more likely to be infected with histoplasmosis?

- Identify at least two similarities between histoplasmosis and tuberculosis.

Coccidioidomycosis

Infection by the dimorphic fungus Coccidioides immitis causes coccidioidomycosis. Because the microbe is endemic to the San Joaquin Valley of California, the disease is sometimes referred to as Valley fever. A related species that causes similar infections is found in semi-arid and arid regions of the southwestern United States, Mexico, and Central and South America.[2]

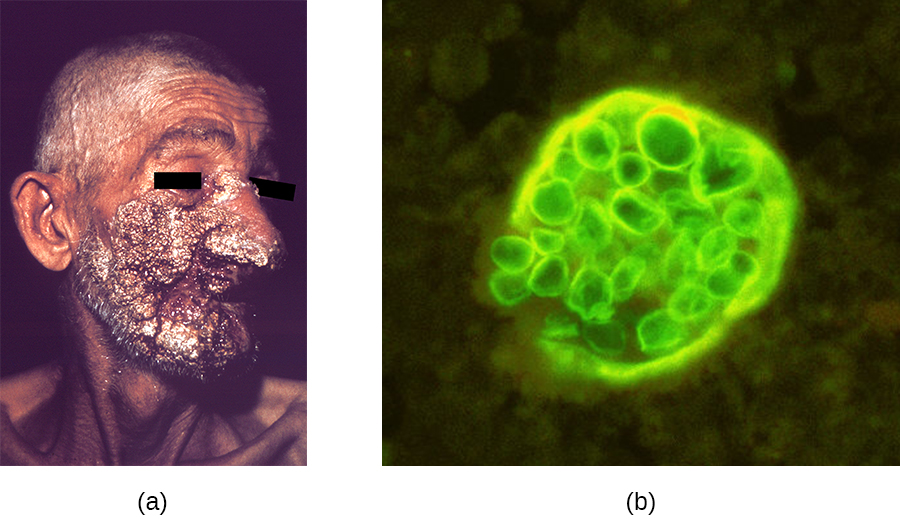

Like histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis is acquired by inhaling fungal spores—in this case, arthrospores formed by hyphal fragmentation. Once in the body, the fungus differentiates into spherules that are filled with endospores. Most C. immitis infections are asymptomatic and self-limiting. However, the infection can be very serious for immunocompromised patients. The endospores may be transported in the blood, disseminating the infection and leading to the formation of granulomatous lesions on the face and nose (Figure 23.20). In severe cases, other major organs can become infected, leading to serious complications such as fatal meningitis.

Coccidioidomycosis can be diagnosed by culturing clinical samples. C. immitis readily grows on laboratory fungal media, such as Sabouraud’s dextrose agar, at 35 °C (95 °F). Culturing the fungus, however, is rather dangerous. C. immitis is one of the most infectious fungal pathogens known and is capable of causing laboratory-acquired infections. Indeed, until 2012, this organism was considered a “select agent” of bioterrorism and classified as a BSL-3 microbe. Serological tests for antibody production are more often used for diagnosis. Although mild cases generally do not require intervention, disseminated infections can be treated with intravenous antifungal drugs like amphotericin B.

CLINICAL FOCUS: Resolution

John’s negative RIDT tests do not rule out influenza, since false-negative results are common, but the Legionella infection still must be treated with antibiotic therapy and is the more serious condition. John’s prognosis is good, provided the physician can find an antibiotic therapy to which the infection responds.

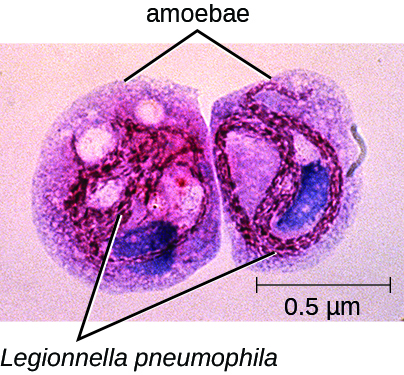

While John was undergoing treatment, three of the employees from the home improvement store also reported to the clinic with very similar symptoms. All three were older than 55 years and had Legionella antigen in their urine; L. pneumophila was also isolated from their sputum. A team from the health department was sent to the home improvement store to identify a probable source for these infections. Their investigation revealed that about 3 weeks earlier, the store’s air conditioning system, which was located where the employees ate lunch, had been undergoing maintenance. L. pneumophila was isolated from the cooling coils of the air conditioning system and intracellular L. pneumophila was observed in amoebae in samples of condensed water from the cooling coils as well (Figure 23.21). The amoebae provide protection for the Legionella bacteria and are known to enhance their pathogenicity.[3]

In the wake of the infections, the store ordered a comprehensive cleaning of the air conditioning system and implemented a regular maintenance program to prevent the growth of biofilms within the cooling tower. They also reviewed practices at their other facilities.

After a month of rest at home, John recovered from his infection enough to return to work, as did the other three employees of the store. However, John experienced lethargy and joint pain for more than a year after his treatment.

Go back to the previous Clinical Focus box.

Blastomycosis

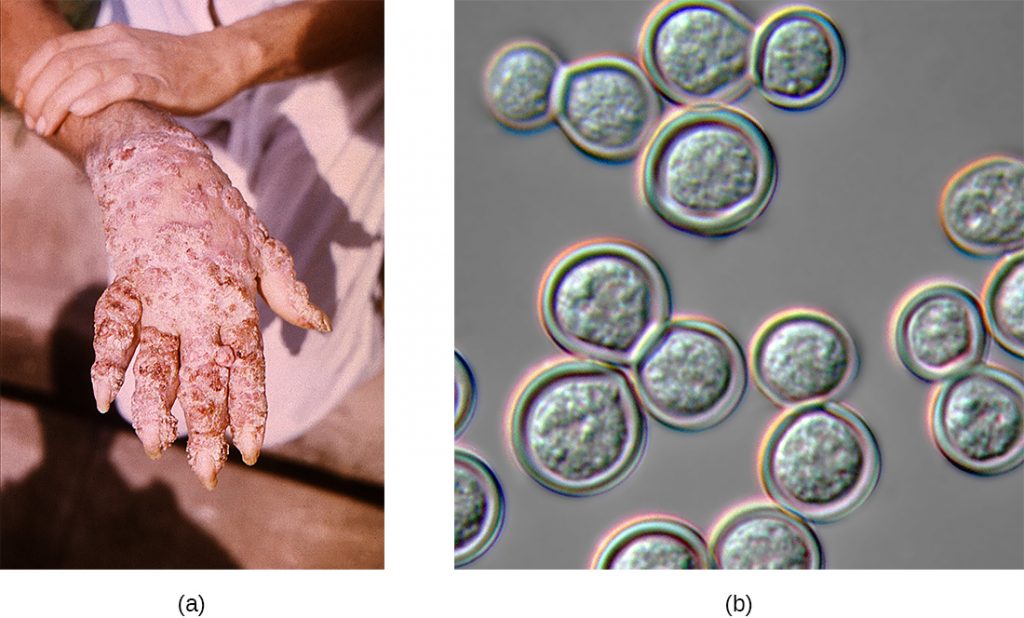

Blastomycosis is a rare disease caused by another dimorphic fungus, Blastomyces dermatitidis. Like Histoplasma and Coccidioides, Blastomyces uses the soil as a reservoir, and fungal spores can be inhaled from disturbed soil. The pulmonary form of blastomycosis generally causes mild flu-like symptoms and is self-limiting. It can, however, become disseminated in immunocompromised people, leading to chronic cutaneous disease with subcutaneous lesions on the face and hands (Figure 23.22). These skin lesions eventually become crusty and discoloured and can result in deforming scars. Systemic blastomycosis is rare, but if left untreated, it is always fatal.

Preliminary diagnosis of pulmonary blastomycosis can be made by observing the characteristic budding yeast forms in sputum samples. Commercially available urine antigen tests are now also available. Additional confirmatory tests include serological assays such as immunodiffusion tests or EIA. Most cases of blastomycosis respond well to amphotericin B or ketoconazole treatments.

Mucormycosis

A variety of fungi in the order Mucorales cause mucormycosis, a rare fungal disease. These include bread moulds, like Rhizopus and Mucor; the most commonly associated species is Rhizopus arrhizus (oryzae) (see Algae). These fungi can colonize many different tissues in immunocompromised patients, but often infect the skin, sinuses, or the lungs.

Although most people are regularly exposed to the causative agents of mucormycosis, infections in healthy individuals are rare. Exposure to spores from the environment typically occurs through inhalation, but the spores can also infect the skin through a wound or the gastrointestinal tract if ingested. Respiratory mucormycosis primarily affects immunocompromised individuals, such as patients with cancer or those who have had a transplant.[4]

After the spores are inhaled, the fungi grow by extending hyphae into the host’s tissues. Infections can occur in both the upper and lower respiratory tracts. Rhinocerebral mucormycosis is an infection of the sinuses and brain; symptoms include headache, fever, facial swelling, congestion, and tissue necrosis causing black lesions in the oral cavity. Pulmonary mucormycosis is an infection of the lungs; symptoms include fever, cough, chest pain, and shortness of breath. In severe cases, infections may become disseminated and involve the central nervous system, leading to coma and death.[5]

Diagnosing mucormycosis can be challenging. Currently, there are no serological or PCR-based tests available to identify these infections. Tissue biopsy specimens must be examined for the presence of the fungal pathogens. The causative agents, however, are often difficult to distinguish from other filamentous fungi. Infections are typically treated by the intravenous administration of amphotericin B, and superficial infections are removed by surgical debridement. Since the patients are often immunocompromised, viral and bacterial secondary infections commonly develop. Mortality rates vary depending on the site of the infection, the causative fungus, and other factors, but a recent study found an overall mortality rate of 54%.[6]

- Compare the modes of transmission for coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, and mucormycosis.

- In general, which are more serious: the pulmonary or disseminated forms of these infections?

Aspergillosis

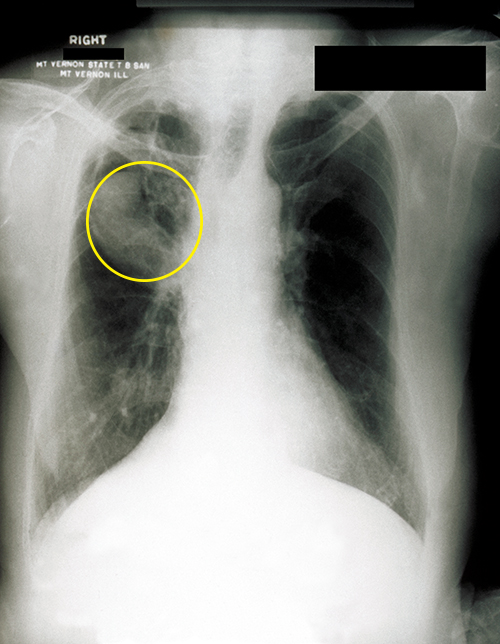

Aspergillus is a common filamentous fungus found in soils and organic debris. Nearly everyone has been exposed to this mould, yet very few people become sick. In immunocompromised patients, however, Aspergillus may become established and cause aspergillosis. Inhalation of spores can lead to asthma-like allergic reactions. The symptoms commonly include shortness of breath, wheezing, coughing, runny nose, and headaches. Fungal balls, or aspergilloma, can form when hyphal colonies collect in the lungs (Figure 23.33). The fungal hyphae can invade the host tissues, leading to pulmonary hemorrhage and a bloody cough. In severe cases, the disease may progress to a disseminated form that is often fatal. Death most often results from pneumonia or brain hemorrhages.

Laboratory diagnosis typically requires chest radiographs and a microscopic examination of tissue and respiratory fluid samples. Serological tests are available to identify Aspergillus antigens. In addition, a skin test can be performed to determine if the patient has been exposed to the fungus. This test is similar to the Mantoux tuberculin skin test used for tuberculosis. Aspergillosis is treated with intravenous antifungal agents, including itraconazole and voriconazole. Allergic symptoms can be managed with corticosteroids because these drugs suppress the immune system and reduce inflammation. However, in disseminated infections, corticosteroids must be discontinued to allow a protective immune response to occur.

Pneumocystis Pneumonia

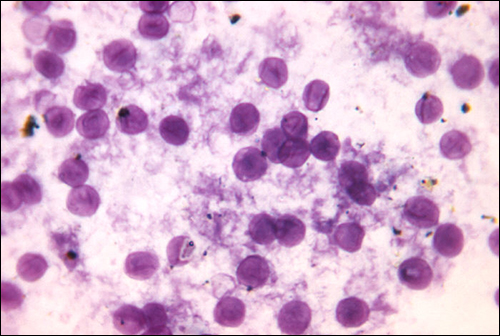

A type of pneumonia called Pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) is caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii. Once thought to be a protozoan, this organism was formerly named P. carinii but it has been reclassified as a fungus and renamed based on biochemical and genetic analyses. Pneumocystis is a leading cause of pneumonia in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and can be seen in other compromised patients and premature infants. Respiratory infection leads to fever, cough, and shortness of breath. Diagnosis of these infections can be difficult. The organism is typically identified by microscopic examination of tissue and fluid samples from the lungs (Figure 23.34). A PCR-based test is available to detect P. jirovecii in asymptomatic patients with AIDS. The best treatment for these infections is the combination drug trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (TMP/SMZ). These sulfa drugs often have adverse effects, but the benefits outweigh these risks. Left untreated, PCP infections are often fatal.

Cryptococcosis

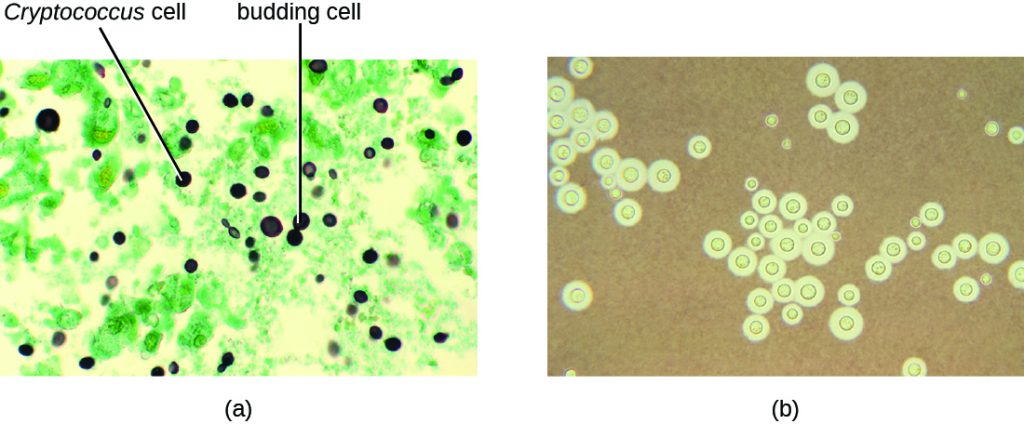

Infection by the encapsulated yeast Cryptococcus neoformans causes cryptococcosis. This fungus is ubiquitous in the soil and can be isolated from bird faeces. Immunocompromised people are infected by inhaling basidiospores found in aerosols. The thick polysaccharide capsule surrounding these microbes enables them to avoid clearance by the alveolar macrophage. Initial symptoms of infection include fever, fatigue, and a dry cough. In immunocompromised patients, pulmonary infections often disseminate to the brain. The resulting meningitis produces headaches, sensitivity to light, and confusion. Left untreated, such infections are often fatal.

Cryptococcus infections are often diagnosed based on microscopic examination of lung tissues or cerebrospinal fluids. India ink preparations (Figue 23.35) can be used to visualize the extensive capsules that surround the yeast cells. Serological tests are also available to confirm the diagnosis. Amphotericin B, in combination with flucytosine, is typically used for the initial treatment of pulmonary infections. Amphotericin B is a broad-spectrum antifungal drug that targets fungal cell membranes. It can also adversely impact host cells and produce side effects. For this reason, clinicians must carefully balance the risks and benefits of treatments in these patients. Because it is difficult to eradicate cryptococcal infections, patients usually need to take fluconazole for up to 6 months after treatment with amphotericin B and flucytosine to clear the fungus. Cryptococcal infections are more common in immunocompromised people, such as those with AIDS. These patients typically require life-long suppressive therapy to control this fungal infection.

- What populations are most at risk for developing Pneumocystis pneumonia or cryptococcosis?

- Why are these infections fatal if left untreated?

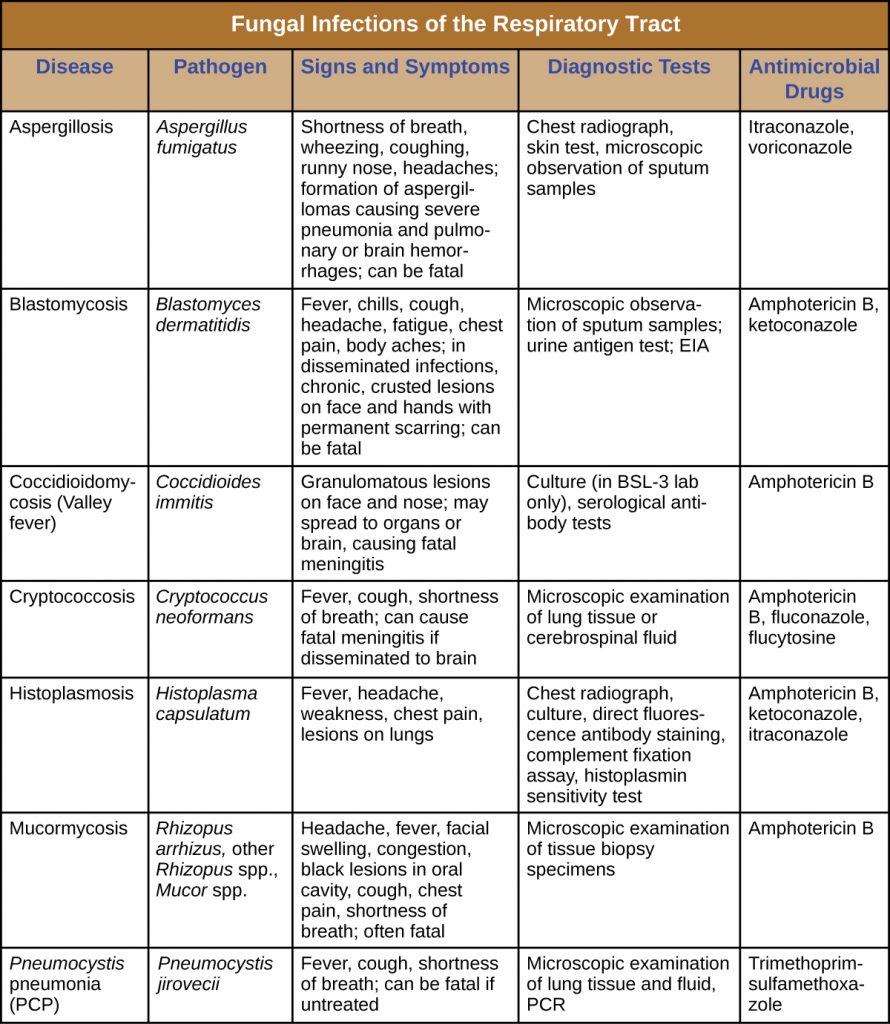

DISEASE PROFILE: Fungal Diseases of the Respiratory Tract

Most respiratory mycoses are caused by fungi that inhabit the environment. Such infections are generally transmitted via inhalation of fungal spores and cannot be transmitted between humans. In addition, healthy people are generally not susceptible to infection even when exposed; the fungi are only virulent enough to establish infection in patients with HIV, AIDS, or another condition that compromises the immune defences. Table 23.8 summarizes the features of important respiratory mycoses.

Table 23.8. Fungal Infections of the Respiratory Tract

Key Takeaways

- Fungal pathogens rarely cause respiratory disease in healthy individuals, but inhalation of fungal spores can cause severe pneumonia and systemic infections in immunocompromised patients.

- Antifungal drugs like amphotericin B can control most fungal respiratory infections.

- Histoplasmosis is caused by a mould that grows in soil rich in bird or bat droppings. Few exposed individuals become sick, but vulnerable individuals are susceptible. The yeast-like infectious cells grow inside phagocytes.

- Coccidioidomycosis is also acquired from soil and, in some individuals, will cause lesions on the face. Extreme cases may infect other organs, causing death.

- Blastomycosis, a rare disease caused by a soil fungus, typically produces a mild lung infection but can become disseminated in the immunocompromised. Systemic cases are fatal if untreated.

- Mucormycosis is a rare disease, caused by fungi of the order Mucorales. It primarily affects immunocompromised people. Infection involves growth of the hyphae into infected tissues and can lead to death in some cases.

- Aspergillosis, caused by the common soil fungus Aspergillus, infects immunocompromised people. Hyphal balls may impede lung function and hyphal growth into tissues can cause damage. Disseminated forms can lead to death.

- Pneumocystis pneumonia is caused by the fungus P. jirovecii. The disease is found in patients with AIDS and other immunocompromised individuals. Sulfa drug treatments have side effects, but untreated cases may be fatal.

- Cryptococcosis is caused by Cryptococcus neoformans. Lung infections may move to the brain, causing meningitis, which can be fatal.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- Which pulmonary fungal infection is most likely to be confused with tuberculosis? How can we discriminate between these two types of infection?

- Compare and contrast aspergillosis and mucormycosis.

Critical Thinking

- Why are fungal pulmonary infections rarely transmissible from person to person?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_22_04_Coccidioid

- OSC_Microbio_22_04_Legion

- OSC_Microbio_22_04_Blasto

- OSC_Microbio_22_04_Aspirgil

- OSC_Microbio_22_04_jirovecii

- NE Manos et al. “Geographic Variation in the Prevalence of Histoplasmin Sensitivity.” Dis Chest 29, no. 6 (1956):649–668. ↵

- DR Hospenthal. “Coccioidomycosis.” Medscape. 2015. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/215978-overview. Accessed May 14, 2019. ↵

- HY Lau and NJ Ashbolt. “The Role of Biofilms and Protozoa in Legionella Pathogenesis: Implications for Drinking Water.” Journal of Applied Microbiology 107 no. 2 (2009):368–378. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Fungal Diseases. Definition of Mucormycosis.” 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/mucormycosis/definition.html. Accessed May 14, 2019. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Fungal Diseases. Symptoms of Mucormycosis.” 2015 http://www.cdc.gov/fungal/diseases/mucormycosis/symptoms.html. Accessed May 14, 2019. ↵

- MM Roden et al. “Epidemiology and Outcome of Zygomycosis: A Review of 929 Reported Cases.” Clinical Infectious Diseases 41 no. 5 (2005):634–653. ↵