25. Digestive System Infections

25.4 Viral Infections of the Gastrointestinal Tract

Learning Objectives

- Identify the most common viruses that can cause infections of the GI tract

- Compare the major characteristics of specific viral diseases affecting the GI tract and liver

In the developing world, acute viral gastroenteritis is devastating and a leading cause of death for children.[1] Worldwide, diarrhoea is the second leading cause of mortality for children under age five, and 70% of childhood gastroenteritis is viral.[2] As discussed, there are a number of bacteria responsible for diarrhoea, but viruses can also cause diarrhoea. E. coli and rotavirus are the most common causative agents in the developing world. In this section, we will discuss rotaviruses and other, less common viruses that can also cause gastrointestinal illnesses.

Gastroenteritis Caused by Rotaviruses

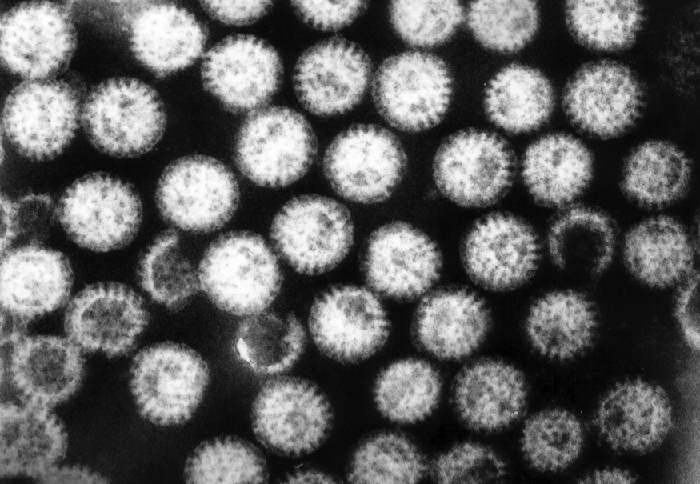

Rotaviruses are double-stranded RNA viruses in the family Reoviridae. They are responsible for common diarrhoeal illness, although prevention through vaccination is becoming more common. The virus is primarily spread by the faecal-oral route (Figure 25.21).

These viruses are widespread in children, especially in day-care centres. The CDC estimates that 95% of children in the United States have had at least one rotavirus infection by the time they reach age five.[3] Due to the memory of the body’s immune system, adults who come into contact with rotavirus will not contract the infection or, if they do, are asymptomatic. The elderly, however, are vulnerable to rotavirus infection due to weakening of the immune system with age, so infections can spread through nursing homes and similar facilities. In these cases, the infection may be transmitted from a family member who may have subclinical or clinical disease. The virus can also be transmitted from contaminated surfaces, on which it can survive for some time.

Infected individuals exhibit fever, vomiting, and diarrhoea. The virus can survive in the stomach following a meal, but is normally found in the small intestines, particularly the epithelial cells on the villi. Infection can cause food intolerance, especially with respect to lactose. The illness generally appears after an incubation period of about two days and lasts for approximately one week (three to eight days). Without supportive treatment, the illness can cause severe fluid loss, dehydration, and even death. Even with milder illness, repeated infections can potentially lead to malnutrition, especially in developing countries, where rotavirus infection is common due to poor sanitation and lack of access to clean drinking water. Patients (especially children) who are malnourished after an episode of diarrhoea are more susceptible to future diarrhoeal illness, increasing their risk of death from rotavirus infection.

The most common clinical tool for diagnosis is enzyme immunoassay, which detects the virus from faecal samples. Latex agglutination assays are also used. Additionally, the virus can be detected using electron microscopy and RT-PCR.

Treatment is supportive with oral rehydration therapy. Preventive vaccination is also available. In the United States, rotavirus vaccines are part of the standard vaccine schedule and administration follows the guidelines of the World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO recommends that all infants worldwide receive the rotavirus vaccine, the first dose between six and 15 weeks of age and the second before 32 weeks.[4]

Gastroenteritis Caused by Noroviruses

Noroviruses, commonly identified as Norwalk viruses, are caliciviruses. Several strains can cause gastroenteritis. There are millions of cases a year, predominately in infants, young children, and the elderly. These viruses are easily transmitted and highly contagious. They are known for causing widespread infections in groups of people in confined spaces, such as on cruise ships. The viruses can be transmitted through direct contact, through touching contaminated surfaces, and through contaminated food. Because the virus is not killed by disinfectants used at standard concentrations for killing bacteria, the risk of transmission remains high, even after cleaning.

The signs and symptoms of norovirus infection are similar to those for rotavirus, with watery diarrhoea, mild cramps, and fever. Additionally, these viruses sometimes cause projectile vomiting. The illness is usually relatively mild, develops 12 to 48 hours after exposure, and clears within a couple of days without treatment. However, dehydration may occur.

Norovirus can be detected using PCR or enzyme immunoassay (EIA) testing. RT-qPCR is the preferred approach as EIA is insufficiently sensitive. If EIA is used for rapid testing, diagnosis should be confirmed using PCR. No medications are available, but the illness is usually self-limiting. Rehydration therapy and electrolyte replacement may be used. Good hygiene, hand washing, and careful food preparation reduce the risk of infection.

Gastroenteritis Caused by Astroviruses

Astroviruses are single-stranded RNA viruses (family Astroviridae) that can cause severe gastroenteritis, especially in infants and children. Signs and symptoms include diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, fever, abdominal pain, headache, and malaise. The viruses are transmitted through the faecal-oral route (contaminated food or water). For diagnosis, stool samples are analyzed. Testing may involve enzyme immunoassays and immune electron microscopy. Treatment involves supportive rehydration and electrolyte replacement if needed.

- Why are rotaviruses, noroviruses, and astroviruses more common in children?

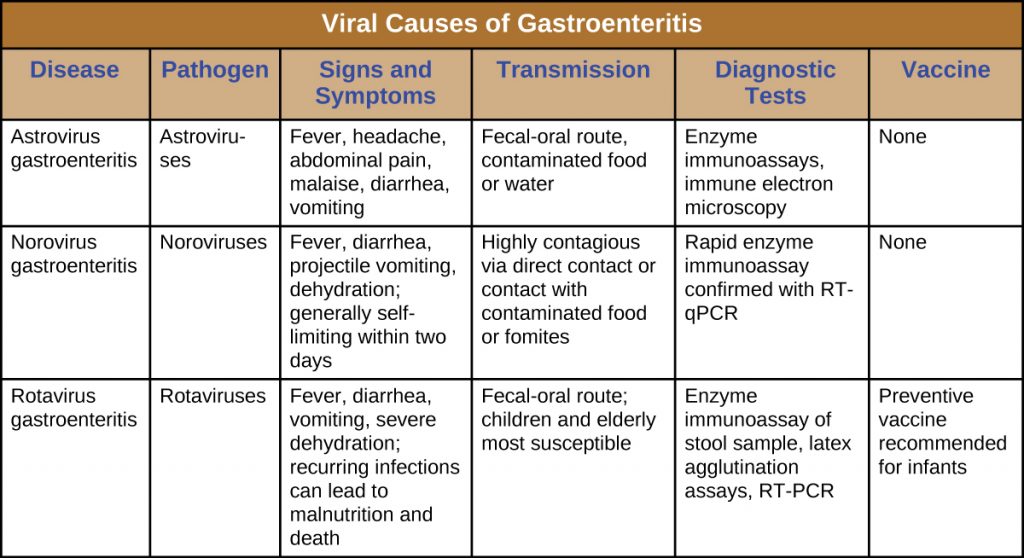

DISEASE PROFILE: Viral Infections of the gastrointestinal Tract

A number of viruses can cause gastroenteritis, characterized by inflammation of the GI tract and other signs and symptoms with a range of severities. As with bacterial GI infections, some cases can be relatively mild and self-limiting, while others can become serious and require intensive treatment. Antimicrobial drugs are generally not used to treat viral gastroenteritis; generally, these illnesses can be treated effectively with rehydration therapy to replace fluids lost in bouts of diarrhoea and vomiting. Because most viral causes of gastroenteritis are quite contagious, the best preventive measures involve avoiding and/or isolating infected individuals and limiting transmission through good hygiene and sanitation.

Table 25.3. Viral Infections of the Gastrointestinal Tract

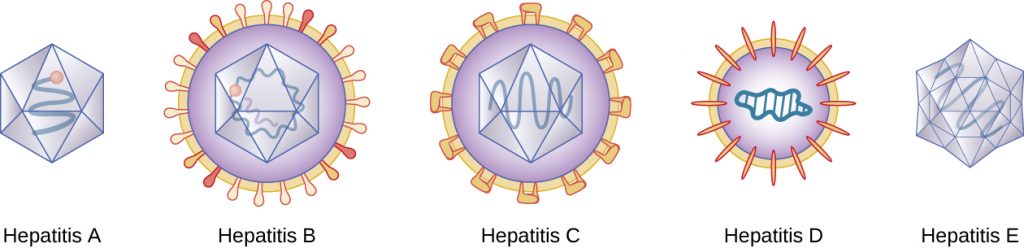

Hepatitis

Hepatitis is a general term meaning inflammation of the liver, which can have a variety of causes. In some cases, the cause is viral infection. There are five main hepatitis viruses that are clinically significant: hepatitisviruses A (HAV), B (HBV), C (HCV), D, (HDV) and E (HEV) (Figure 25.22). Note that other viruses, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), yellow fever, and cytomegalovirus (CMV) can also cause hepatitis and are discussed in Viral Infections of the Circulatory and Lymphatic Systems.

Although the five hepatitis viruses differ, they can cause some similar signs and symptoms because they all have an affinity for hepatocytes (liver cells). HAV and HEV can be contracted through ingestion while HBV, HCV, and HDV are transmitted by parenteral contact. It is possible for individuals to become long term or chronic carriers of hepatitis viruses.

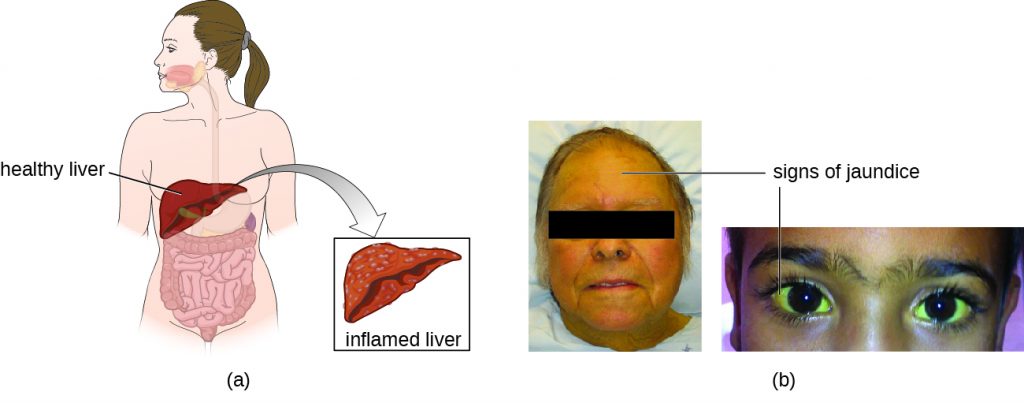

The virus enters the blood (viraemia), spreading to the spleen, the kidneys, and the liver. During viral replication, the virus infects hepatocytes. The inflammation is caused by the hepatocytes replicating and releasing more hepatitis virus. Signs and symptoms include malaise, anorexia, loss of appetite, dark urine, pain in the upper right quadrant of the abdomen, vomiting, nausea, diarrhoea, joint pain, and grey stool. Additionally, when the liver is diseased or injured, it is unable to break down hemoglobin effectively, and bilirubin can build up in the body, giving the skin and mucous membranes a yellowish colour, a condition called jaundice (Figure 25.23). In severe cases, death from liver necrosis may occur.

Despite having many similarities, each of the hepatitis viruses has its own unique characteristics. HAV is generally transmitted through the faecal-oral route, close personal contact, or exposure to contaminated water or food. Hepatitis A can develop after an incubation period of 15 to 50 days (the mean is 30). It is normally mild or even asymptomatic and is usually self-limiting within weeks to months. A more severe form, fulminant hepatitis, rarely occurs but has a high fatality rate of 70–80%. Vaccination is available and is recommended especially for children (between ages one and two), those traveling to countries with higher risk, those with liver disease and certain other conditions, and drug users.

Although HBV is associated with similar signs and symptoms, transmission and outcomes differ. This virus has a mean incubation period of 120 days and is generally associated with exposure to infectious blood or body fluids such as semen or saliva. Exposure can occur through skin puncture, across the placenta, or through mucosal contact, but it is not spread through casual contact such as hugging, hand holding, sneezing, or coughing, or even through breastfeeding or kissing. Risk of infection is greatest for those who use intravenous drugs or who have sexual contact with an infected individual. Health-care workers are also at risk from needle sticks and other injuries when treating infected patients. The infection can become chronic and may progress to cirrhosis or liver failure. It is also associated with liver cancer. Chronic infections are associated with the highest mortality rates and are more common in infants. Approximately 90% of infected infants become chronic carriers, compared with only 6–10% of infected adults.[5] Vaccination is available and is recommended for children as part of the standard vaccination schedule (one dose at birth and the second by 18 months of age) and for adults at greater risk (e.g., those with certain diseases, intravenous drug users, and those who have sex with multiple partners). Health-care agencies are required to offer the HBV vaccine to all workers who have occupational exposure to blood and/or other infectious materials.

HCV is often undiagnosed and therefore may be more widespread than is documented. It has a mean incubation period of 45 days and is transmitted through contact with infected blood. Although some cases are asymptomatic and/or resolve spontaneously, 75%–85% of infected individuals become chronic carriers. Nearly all cases result from parenteral transmission often associated with IV drug use or transfusions. The risk is greatest for individuals with past or current history of intravenous drug use or who have had sexual contact with infected individuals. It has also been spread through contaminated blood products and can even be transmitted through contaminated personal products such as toothbrushes and razors. New medications have recently been developed that show great effectiveness in treating HCV and that are tailored to the specific genotype causing the infection.

HDV is uncommon in the United States and only occurs in individuals who are already infected with HBV, which it requires for replication. Therefore, vaccination against HBV is also protective against HDV infection. HDV is transmitted through contact with infected blood.

HEV infections are also rare in the United States but many individuals have a positive antibody titre for HEV. The virus is most commonly spread by the faecal-oral route through food and/or water contamination, or person-to-person contact, depending on the genotype of the virus, which varies by location. There are four genotypes that differ somewhat in their mode of transmission, distribution, and other factors (for example, two are zoonotic and two are not, and only one causes chronic infection). Genotypes three and four are only transmitted through food, while genotypes one and two are also transmitted through water and faecal-oral routes. Genotype one is the only type transmitted person-to-person and is the most common cause of HEV outbreaks. Consumption of undercooked meat, especially deer or pork, and shellfish can lead to infection. Genotypes three and four are zoonoses, so they can be transmitted from infected animals that are consumed. Pregnant women are at particular risk. This disease is usually self-limiting within two weeks and does not appear to cause chronic infection.

General laboratory testing for hepatitis begins with blood testing to examine liver function (Table 25.3). When the liver is not functioning normally, the blood will contain elevated levels of alkaline phosphatase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), direct bilirubin, total bilirubin, serum albumin, serum total protein, and calculated globulin, albumin/globulin (A/G) ratio. Some of these are included in a complete metabolic panel (CMP), which may first suggest a possible liver problem and indicate the need for more comprehensive testing. A hepatitis virus serological test panel can be used to detect antibodies for hepatitis viruses A, B, C, and sometimes D. Additionally, other immunological and genomic tests are available.

Specific treatments other than supportive therapy, rest, and fluids are often not available for hepatitis virus infection, except for HCV, which is often self-limited. Immunoglobulins can be used prophylactically following possible exposure. Medications are also used, including interferon alpha 2b and antivirals (e.g., lamivudine, entecavir, adefovir, and telbivudine) for chronic infections. Hepatitis C can be treated with interferon (as monotherapy or combined with other treatments), protease inhibitors, and other antivirals (e.g., the polymerase inhibitor sofosbuvir). Combination treatments are commonly used. Antiviral and immunosuppressive medications may be used for chronic cases of HEV. In severe cases, liver transplants may be necessary. Additionally, vaccines are available to prevent infection with HAV and HBV. The HAV vaccine is also protective against HEV. The HBV vaccine is also protective against HDV. There is no vaccine against HCV.

Learn more information about heptatitisvirus infections.

- Why do the five different hepatitis viruses all cause similar signs and symptoms?

MICRO CONNECTIONS: Preventing HBV Transmission in Health-Care Settings

Hepatitis B was once a leading on-the-job hazard for health-care workers. Many health-care workers over the years have become infected, some developing cirrhosis and liver cancer. In 1982, the CDC recommended that health-care workers be vaccinated against HBV, and rates of infection have declined since then. Even though vaccination is now common, it is not always effective and not all individuals are vaccinated. Therefore, there is still a small risk for infection, especially for health-care workers working with individuals who have chronic infections, such as drug addicts, and for those with higher risk of needle sticks, such as phlebotomists. Dentists are also at risk.

Health-care workers need to take appropriate precautions to prevent infection by HBV and other illnesses. Blood is the greatest risk, but other body fluids can also transmit infection. Damaged skin, as occurs with eczema or psoriasis, can also allow transmission. Avoiding contact with body fluids, especially blood, by wearing gloves and face protection and using disposable syringes and needles reduce the risk of infection. Washing exposed skin with soap and water is recommended. Antiseptics may also be used, but may not help. Post-exposure treatment, including treatment with hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and vaccination, may be used in the event of exposure to the virus from an infected patient. Detailed protocols are available for managing these situations. The virus can remain infective for up to seven days when on surfaces, even if no blood or other fluids are visible, so it is important to consider the best choices for disinfecting and sterilizing equipment that could potentially transmit the virus. The CDC recommends a solution of 10% bleach to disinfect surfaces.[6] Finally, testing blood products is important to reduce the risk of transmission during transfusions and similar procedures.

DISEASE PROFILE: Viral Hepatitis

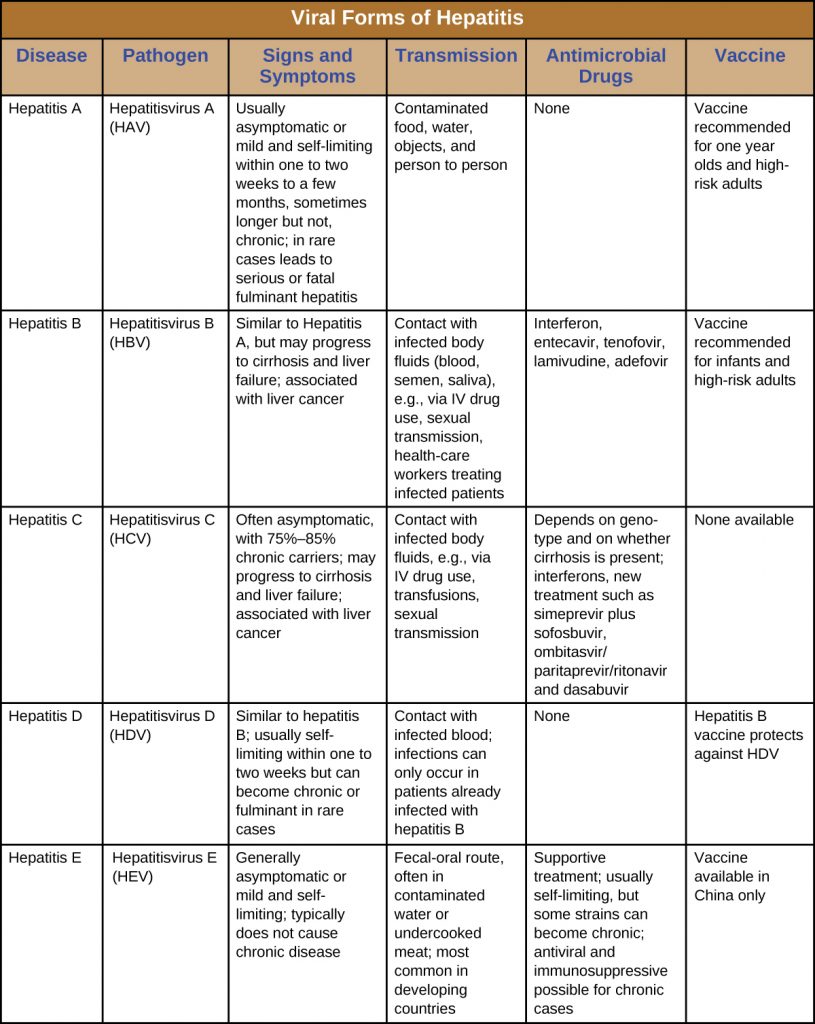

Hepatitis involves inflammation of the liver that typically manifests with signs and symptoms such as jaundice, nausea, vomiting, joint pain, grey stool, and loss of appetite. However, the severity and duration of the disease can vary greatly depending on the causative agent. Some infections may be completely asymptomatic, whereas others may be life threatening. The five different viruses capable of causing hepatitis are compared in Table 25.3. For the sake of comparison, this table presents only the unique aspects of each form of viral hepatitis, not the commonalities.

Table 25.3. Viral forms of Hepatitis

Key Takeaways

- Common viral causes of gastroenteritis include rotaviruses, noroviruses, and astroviruses.

- Hepatitis may be caused by several unrelated viruses: hepatitis viruses A, B, C, D, and E.

- The hepatitis viruses differ in their modes of transmission, treatment, and potential for chronic infection.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- Which forms of viral hepatitis are transmitted through the faecal-oral route?

Critical Thinking

- Based on what you know about HBV, what are some ways that its transmission could be reduced in a health-care setting?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_24_04_Rotavirus

- OSC_Microbio_24_04_Hepatitis

- OSC_Microbio_24_04_HepJaundic

- microbiology sign © Nick Youngson

- OSC_Microbio_24_04_HepTBL

- Caleb K. King, Roger Glass, Joseph S. Bresee, Christopher Duggan. “Managing Acute Gastroenteritis Among Children: Oral Rehydration, Maintenance, and Nutritional Therapy.” MMWR 52 (2003) RR16: pp. 1–16. http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/rr5216a1.htm. ↵

- Elizabeth Jane Elliott. “Acute Gastroenteritis in Children.” British Medical Journal 334 (2007) 7583: 35–40, doi: 10.1136/bmj.39036.406169.80; S. Ramani and G. Kang. “Viruses Causing Diarrhoea in the Developing World.” Current Opinions in Infectious Diseases 22 (2009) 5: pp. 477–482. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328330662f; Michael Vincent F Tablang. “Viral Gastroenteritis.” Medscape. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/176515-overview. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Rotavirus,” The Pink Book. Updated May 14, 2019. http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/pinkbook/rota.html. ↵

- World Health Organization. “Rotavirus.” Immunization, Vaccines, and Biologicals. Updated May 14, 2019. https://www.who.int/immunization/global_vaccine_action_plan/en/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “The ABCs of Hepatitis.” Updated May 14, 2019. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/resources/professionals/pdfs/abctable.pdf. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Hepatitis B FAQs for Health Professionals.” Updated May 14, 2019. http://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/HBV/HBVfaq.htm. ↵