19. Adaptive Specific Host Defenses

19.5 Vaccines

Learning Objectives

- Compare the various kinds of artificial immunity

- Differentiate between variolation and vaccination

- Describe different types of vaccines and explain their respective advantages and disadvantages

For many diseases, prevention is the best form of treatment, and few strategies for disease prevention are as effective as vaccination. Vaccination is a form of artificial immunity. By artificially stimulating the adaptive immune defences, a vaccine triggers memory cell production similar to that which would occur during a primary response. In so doing, the patient is able to mount a strong secondary response upon exposure to the pathogen—but without having to first suffer through an initial infection. In this section, we will explore several different kinds of artificial immunity along with various types of vaccines and the mechanisms by which they induce artificial immunity.

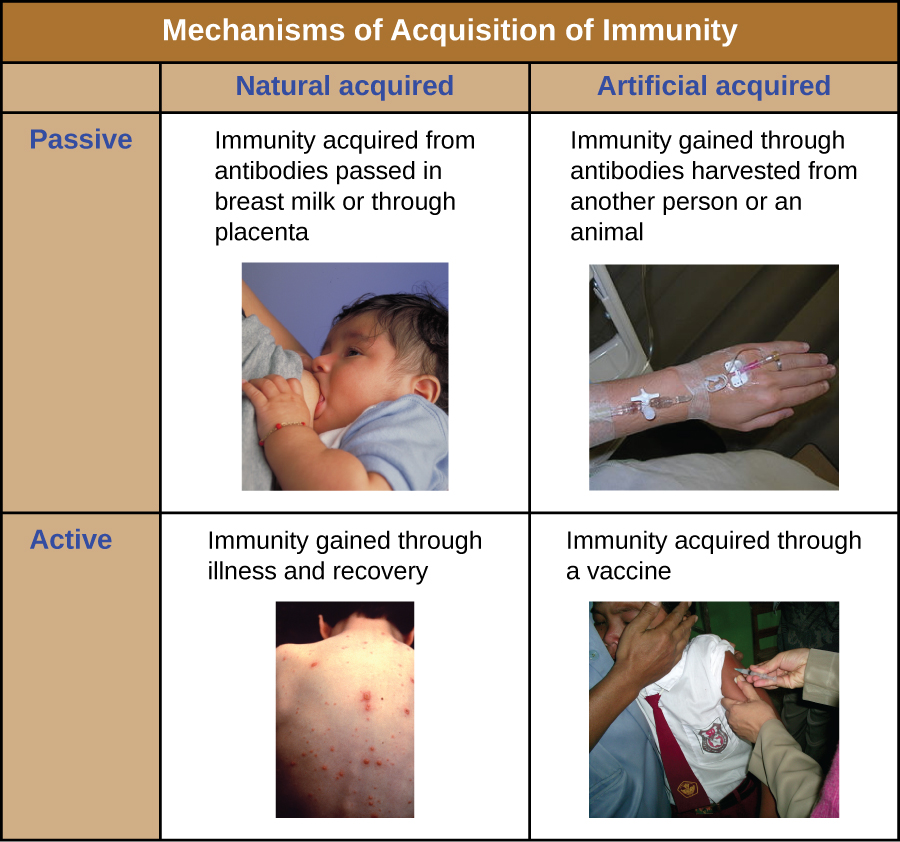

Classifications of Adaptive Immunity

All forms of adaptive immunity can be described as either active or passive. Active immunity refers to the activation of an individual’s own adaptive immune defences, whereas passive immunity refers to the transfer of adaptive immune defences from another individual or animal. Active and passive immunity can be further subdivided based on whether the protection is acquired naturally or artificially.

Natural active immunity is adaptive immunity that develops after natural exposure to a pathogen (Figure 19.24). Examples would include the lifelong immunity that develops after recovery from a chickenpox or measles infection (although an acute infection is not always necessary to activate adaptive immunity). The length of time that an individual is protected can vary substantially depending upon the pathogen and antigens involved. For example, activation of adaptive immunity by protein spike structures during an intracellular viral infection can activate lifelong immunity, whereas activation by carbohydrate capsule antigens during an extracellular bacterial infection may activate shorter-term immunity.

Natural passive immunity involves the natural passage of antibodies from a mother to her child before and after birth. IgG is the only antibody class that can cross the placenta from mother’s blood to the fetal blood supply. Placental transfer of IgG is an important passive immune defence for the infant, lasting up to six months after birth. Secretory IgA can also be transferred from mother to infant through breast milk.

Artificial passive immunity refers to the transfer of antibodies produced by a donor (human or animal) to another individual. This transfer of antibodies may be done as a prophylactic measure (i.e., to prevent disease after exposure to a pathogen) or as a strategy for treating an active infection. For example, artificial passive immunity is commonly used for post-exposure prophylaxis against rabies, hepatitis A, hepatitis B, and chickenpox (in high risk individuals). Active infections treated by artificial passive immunity include cytomegalovirus infections in immunocompromised patients and Ebola virus infections. In 1995, eight patients in the Democratic Republic of the Congo with active Ebola infections were treated with blood transfusions from patients who were recovering from Ebola. Only one of the eight patients died (a 12.5% mortality rate), which was much lower than the expected 80% mortality rate for Ebola in untreated patients.[1] Artificial passive immunity is also used for the treatment of diseases caused by bacterial toxins, including tetanus, botulism, and diphtheria.

Artificial active immunity is the foundation for vaccination. It involves the activation of adaptive immunity through the deliberate exposure of an individual to weakened or inactivated pathogens, or preparations consisting of key pathogen antigens.

- What is the difference between active and passive immunity?

- What kind of immunity is conferred by a vaccine?

Herd Immunity

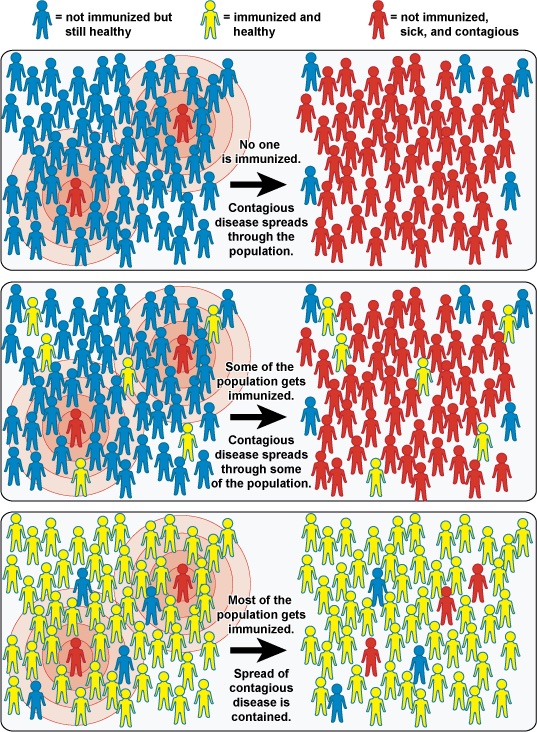

The four kinds of immunity just described result from an individual’s adaptive immune system. For any given disease, an individual may be considered immune or susceptible depending on his or her ability to mount an effective immune response upon exposure. Thus, any given population is likely to have some individuals who are immune and other individuals who are susceptible. If a population has very few susceptible individuals, even those susceptible individuals will be protected by a phenomenon called herd immunity, also called community immunity (Figure 19.25). Herd immunity has nothing to do with an individual’s ability to mount an effective immune response; rather, it occurs because there are too few susceptible individuals in a population for the disease to spread effectively.

Vaccination programs create herd immunity by greatly reducing the number of susceptible individuals in a population. Even if some individuals in the population are not vaccinated, as long as a certain percentage is immune (either naturally or artificially), the few susceptible individuals are unlikely to be exposed to the pathogen. However, because new individuals are constantly entering populations (for example, through birth or relocation), vaccination programs are necessary to maintain herd immunity.

EYE ON ETHICS: Vaccination: Obligation or Choice

A growing number of parents are choosing not to vaccinate their children. They are dubbed “antivaxxers,” and the majority of them believe that vaccines are a cause of autism (or other disease conditions), a link that has now been thoroughly disproven. Others object to vaccines on religious or moral grounds (e.g., the argument that Gardasil vaccination against HPV may promote sexual promiscuity), on personal ethical grounds (e.g., a conscientious objection to any medical intervention), or on political grounds (e.g., the notion that mandatory vaccinations are a violation of individual liberties).[2]

It is believed that this growing number of unvaccinated individuals has led to new outbreaks of whooping cough and measles. We would expect that herd immunity would protect those unvaccinated in our population, but herd immunity can only be maintained if enough individuals are being vaccinated.

Vaccination is clearly beneficial for public health. But from the individual parent’s perspective the view can be murkier. Vaccines, like all medical interventions, have associated risks, and while the risks of vaccination may be extremely low compared to the risks of infection, parents may not always understand or accept the consensus of the medical community. Do such parents have a right to withhold vaccination from their children? Should they be allowed to put their children—and society at large—at risk?

Many governments insist on childhood vaccinations as a condition for entering public school, but it has become easy in most states to opt out of the requirement or to keep children out of the public system. Since the 1970s, West Virginia and Mississippi have had in place a stringent requirement for childhood vaccination, without exceptions, and neither state has had a case of measles since the early 1990s. California lawmakers recently passed a similar law in response to a measles outbreak in 2015, making it much more difficult for parents to opt out of vaccines if their children are attending public schools. Given this track record and renewed legislative efforts, should other states adopt similarly strict requirements?

What role should health-care providers play in promoting or enforcing universal vaccination? Studies have shown that many parents’ minds can be changed in response to information delivered by health-care workers, but is it the place of health-care workers to try to persuade parents to have their children vaccinated? Some health-care providers are understandably reluctant to treat unvaccinated patients. Do they have the right to refuse service to patients who decline vaccines? Do insurance companies have the right to deny coverage to antivaxxers? These are all ethical questions that policymakers may be forced to address as more parents skirt vaccination norms.

Variolation and Vaccination

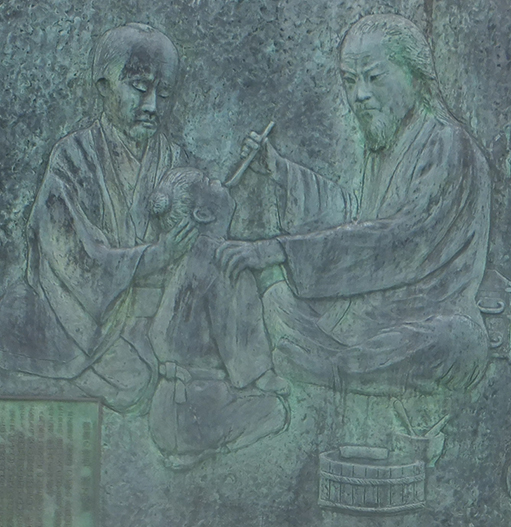

Thousands of years ago, it was first recognized that individuals who survived a smallpox infection were immune to subsequent infections. The practice of inoculating individuals to actively protect them from smallpox appears to have originated in the 10th century in China, when the practice of variolation was described (Figure 19.26). Variolation refers to the deliberate inoculation of individuals with infectious material from scabs or pustules of smallpox victims. Infectious materials were either injected into the skin or introduced through the nasal route. The infection that developed was usually milder than naturally acquired smallpox, and recovery from the milder infection provided protection against the more serious disease.

Although the majority of individuals treated by variolation developed only mild infections, the practice was not without risks. More serious and sometimes fatal infections did occur, and because smallpox was contagious, infections resulting from variolation could lead to epidemics. Even so, the practice of variolation for smallpox prevention spread to other regions, including India, Africa, and Europe.

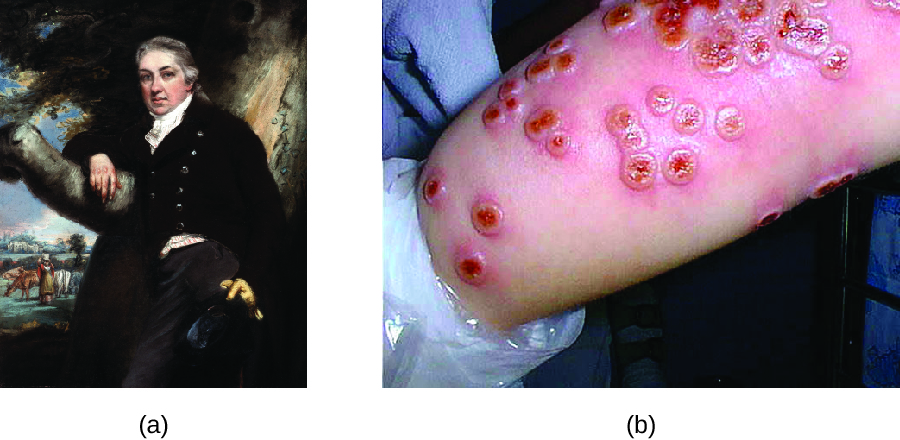

Although variolation had been practiced for centuries, the English physician Edward Jenner (1749–1823) is generally credited with developing the modern process of vaccination. Jenner observed that milkmaids who developed cowpox, a disease similar to smallpox but milder, were immune to the more serious smallpox. This led Jenner to hypothesize that exposure to a less virulent pathogen could provide immune protection against a more virulent pathogen, providing a safer alternative to variolation. In 1796, Jenner tested his hypothesis by obtaining infectious samples from a milkmaid’s active cowpox lesion and injecting the materials into a young boy (Figure 19.27). The boy developed a mild infection that included a low-grade fever, discomfort in his axillae (armpit) and loss of appetite. When the boy was later infected with infectious samples from smallpox lesions, he did not contract smallpox.[3] This new approach was termed vaccination, a name deriving from the use of cowpox (Latin vacca meaning “cow”) to protect against smallpox. Today, we know that Jenner’s vaccine worked because the cowpox virus is genetically and antigenically related to the Variola viruses that caused smallpox. Exposure to cowpox antigens resulted in a primary response and the production of memory cells that identical or related epitopes of Variola virus upon a later exposure to smallpox.

The success of Jenner’s smallpox vaccination led other scientists to develop vaccines for other diseases. Perhaps the most notable was Louis Pasteur, who developed vaccines for rabies, cholera, and anthrax. During the 20th and 21st centuries, effective vaccines were developed to prevent a wide range of diseases caused by viruses (e.g., chickenpox and shingles, hepatitis, measles, mumps, polio, and yellow fever) and bacteria (e.g., diphtheria, pneumococcal pneumonia, tetanus, and whooping cough,).

- What is the difference between variolation and vaccination for smallpox?

- Explain why vaccination is less risky than variolation.

Classes of Vaccines

For a vaccine to provide protection against a disease, it must expose an individual to pathogen-specific antigens that will stimulate a protective adaptive immune response. By its very nature, this entails some risk. As with any pharmaceutical drug, vaccines have the potential to cause adverse effects. However, the ideal vaccine causes no severe adverse effects and poses no risk of contracting the disease that it is intended to prevent. Various types of vaccines have been developed with these goals in mind. These different classes of vaccines are described in the next section and summarized in Table 19.3.

Live Attenuated Vaccines

Live attenuated vaccines expose an individual to a weakened strain of a pathogen with the goal of establishing a subclinical infection that will activate the adaptive immune defences. Pathogens are attenuated to decrease their virulence using methods such as genetic manipulation (to eliminate key virulence factors) or long-term culturing in an unnatural host or environment (to promote mutations and decrease virulence).

By establishing an active infection, live attenuated vaccines stimulate a more comprehensive immune response than some other types of vaccines. Live attenuated vaccines activate both cellular and humoral immunity and stimulate the development of memory for long-lasting immunity. In some cases, vaccination of one individual with a live attenuated pathogen can even lead to natural transmission of the attenuated pathogen to other individuals. This can cause the other individuals to also develop an active, subclinical infection that activates their adaptive immune defences.

Disadvantages associated with live attenuated vaccines include the challenges associated with long-term storage and transport as well as the potential for a patient to develop signs and symptoms of disease during the active infection (particularly in immunocompromised patients). There is also a risk of the attenuated pathogen reverting back to full virulence. Table 19.3 lists examples of live attenuated vaccines.

Inactivated Vaccines

Inactivated vaccines contain whole pathogens that have been killed or inactivated with heat, chemicals, or radiation. For inactivated vaccines to be effective, the inactivation process must not affect the structure of key antigens on the pathogen.

Because the pathogen is killed or inactive, inactivated vaccines do not produce an active infection, and the resulting immune response is weaker and less comprehensive than that provoked by a live attenuated vaccine. Typically the response involves only humoral immunity, and the pathogen cannot be transmitted to other individuals. In addition, inactivated vaccines usually require higher doses and multiple boosters, possibly causing inflammatory reactions at the site of injection.

Despite these disadvantages, inactivated vaccines do have the advantages of long-term storage stability and ease of transport. Also, there is no risk of causing severe active infections. However, inactivated vaccines are not without their side effects. Table 19.3 lists examples of inactivated vaccines.

Subunit Vaccines

Whereas live attenuated and inactive vaccines expose an individual to a weakened or dead pathogen, subunit vaccines only expose the patient to the key antigens of a pathogen—not whole cells or viruses. Subunit vaccines can be produced either by chemically degrading a pathogen and isolating its key antigens or by producing the antigens through genetic engineering. Because these vaccines contain only the essential antigens of a pathogen, the risk of side effects is relatively low. Table 19.3 lists examples of subunit vaccines.

Toxoid Vaccines

Like subunit vaccines, toxoid vaccines do not introduce a whole pathogen to the patient; they contain inactivated bacterial toxins, called toxoids. Toxoid vaccines are used to prevent diseases in which bacterial toxins play an important role in pathogenesis. These vaccines activate humoral immunity that neutralizes the toxins. Table 19.3 lists examples of toxoid vaccines.

Conjugate Vaccines

A conjugate vaccine is a type of subunit vaccine that consists of a protein conjugated to a capsule polysaccharide. Conjugate vaccines have been developed to enhance the efficacy of subunit vaccines against pathogens that have protective polysaccharide capsules that help them evade phagocytosis, causing invasive infections that can lead to meningitis and other serious conditions. The subunit vaccines against these pathogens introduce T-independent capsular polysaccharide antigens that result in the production of antibodies that can opsonize the capsule and thus combat the infection; however, children under the age of two years do not respond effectively to these vaccines. Children do respond effectively when vaccinated with the conjugate vaccine, in which a protein with T-dependent antigens is conjugated to the capsule polysaccharide. The conjugated protein-polysaccharide antigen stimulates production of antibodies against both the protein and the capsule polysaccharide. Table 19.3 lists examples of conjugate vaccines.

Table 19.3. Summary of the classes of vaccines

| Classes of Vaccines | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class | Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Examples |

| Live attenuated | Weakened strain of whole pathogen | Cellular and humoral immunity | Difficult to store and transport | Chickenpox, German measles, measles, mumps, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, yellow fever |

| Long-lasting immunity | Risk of infection in immunocompromised patients | |||

| Transmission to contacts | Risk of reversion | |||

| Inactivated | Whole pathogen killed or inactivated with heat, chemicals, or radiation | Ease of storage and transport | Weaker immunity (humoral only) | Cholera, hepatitis A, influenza, plague, rabies |

| No risk of severe active infection | Higher doses and more boosters required | |||

| Subunit | Immunogenic antigens | Lower risk of side effects | Limited longevity | Anthrax, hepatitis B, influenza, meningitis, papillomavirus, pneumococcal pneumonia, whooping cough |

| Multiple doses required | ||||

| No protection against antigenic variation | ||||

| Toxoid | Inactivated bacterial toxin | Humoral immunity to neutralize toxin | Does not prevent infection | Botulism, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus |

| Conjugate | Capsule polysaccharide conjugated to protein | T-dependent response to capsule | Costly to produce | Meningitis

(Haemophilus influenzae, Streptococcus pneumoniae, Neisseria meningitides) |

| No protection against antigenic variation | ||||

| Better response in young children | May interfere with other vaccines | |||

- What is the risk associated with a live attenuated vaccine?

- Why is a conjugated vaccine necessary in some cases?

MICRO CONNECTIONS: DNA Vaccines

DNA vaccines represent a relatively new and promising approach to vaccination. A DNA vaccine is produced by incorporating genes for antigens into a recombinant plasmid vaccine. Introduction of the DNA vaccine into a patient leads to uptake of the recombinant plasmid by some of the patient’s cells, followed by transcription and translation of antigens and presentation of these antigens with MHC I to activate adaptive immunity. This results in the stimulation of both humoral and cellular immunity without the risk of active disease associated with live attenuated vaccines.

Although most DNA vaccines for humans are still in development, it is likely that they will become more prevalent in the near future as researchers are working on engineering DNA vaccines that will activate adaptive immunity against several different pathogens at once. First-generation DNA vaccines tested in the 1990s looked promising in animal models but were disappointing when tested in human subjects. Poor cellular uptake of the DNA plasmids was one of the major problems impacting their efficacy. Trials of second-generation DNA vaccines have been more promising thanks to new techniques for enhancing cellular uptake and optimizing antigens. DNA vaccines for various cancers and viral pathogens such as HIV, HPV, and hepatitis B and C are currently in development.

Some DNA vaccines are already in use. In 2005, a DNA vaccine against West Nile virus was approved for use in horses in the United States. Canada has also approved a DNA vaccine to protect fish from infectious hematopoietic necrosis virus.[4] A DNA vaccine against Japanese encephalitis virus was approved for use in humans in 2010 in Australia.[5]

CLINICAL FOCUS: Resolution

Based on Olivia’s symptoms, her physician made a preliminary diagnosis of bacterial meningitis without waiting for positive identification from the blood and CSF samples sent to the lab. Olivia was admitted to the hospital and treated with intravenous broad-spectrum antibiotics and rehydration therapy. Over the next several days, her condition began to improve, and new blood samples and lumbar puncture samples showed an absence of microbes in the blood and CSF with levels of white blood cells returning to normal. During this time, the lab produced a positive identification of Neisseria meningitidis, the causative agent of meningococcal meningitis, in her original CSF sample.

N. meningitidis produces a polysaccharide capsule that serves as a virulence factor. N. meningitidis tends to affect infants after they begin to lose the natural passive immunity provided by maternal antibodies. At one year of age, Olivia’s maternal IgG antibodies would have disappeared, and she would not have developed memory cells capable of recognizing antigens associated with the polysaccharide capsule of the N. meningitidis. As a result, her adaptive immune system was unable to produce protective antibodies to combat the infection, and without antibiotics she may not have survived. Olivia’s infection likely would have been avoided altogether had she been vaccinated. A conjugate vaccine to prevent meningococcal meningitis is available and approved for infants as young as two months of age. However, current vaccination schedules in the United States recommend that the vaccine be administered at age 11–12 with a booster at age 16.

Go back to the previous Clinical Focus box.

In countries with developed public health systems, many vaccines are routinely administered to children and adults. Vaccine schedules are changed periodically, based on new information and research results gathered by public health agencies. In the United States, the CDC publishes schedules and other updated information about vaccines.

Key Takeaways

- Adaptive immunity can be divided into four distinct classifications: natural active immunity, natural passive immunity, artificial passive immunity, and artificial active immunity.

- Artificial active immunity is the foundation for vaccination and vaccine development. Vaccination programs not only confer artificial immunity on individuals, but also foster herd immunity in populations.

- Variolation against smallpox originated in the 10th century in China, but the procedure was risky because it could cause the disease it was intended to prevent. Modern vaccination was developed by Edward Jenner, who developed the practice of inoculating patients with infectious materials from cowpox lesions to prevent smallpox.

- Live attenuated vaccines and inactivated vaccines contain whole pathogens that are weak, killed, or inactivated. Subunit vaccines, toxoid vaccines, and conjugate vaccines contain acellular components with antigens that stimulate an immune response.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short answer

- Briefly compare the pros and cons of inactivated versus live attenuated vaccines.

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_18_05_graph

- Community_Immunity

- CNX_UPhysics_06_01_StopLight

- OSC_Microbio_18_05_jenner

- microbiology sign © Nick Youngson

- K. Mupapa, M. Massamba, K. Kibadi, K. Kivula, A. Bwaka, M. Kipasa, R. Colebunders, J. J. Muyembe-Tamfum. “Treatment of Ebola Hemorrhagic Fever with Blood Transfusions from Convalescent Patients.” Journal of Infectious Diseases 179 Suppl. (1999): S18–S23. ↵

- Elizabeth Yale. “Why Anti-Vaccination Movements Can Never Be Tamed.” Religion & Politics, July 22, 2014. http://religionandpolitics.org/2014/07/22/why-anti-vaccination-movements-can-never-be-tamed. ↵

- N. J. Willis. “Edward Jenner and the Eradication of Smallpox.” Scottish Medical Journal 42 (1997): 118–121. ↵

- M. Alonso and J. C. Leong. “Licensed DNA Vaccines Against Infectious Hematopoietic Necrosis Virus (IHNV).” Recent Patents on DNA & Gene Sequences (Discontinued) 7 no. 1 (2013): 62–65, issn 1872-2156/2212-3431. doi 10.2174/1872215611307010009. ↵

- S.B. Halstead and S. J. Thomas. “New Japanese Encephalitis Vaccines: Alternatives to Production in Mouse Brain.” Expert Review of Vaccines 10 no. 3 (2011): 355–64. ↵