1. An Invisible World

1.3 Types of Microorganisms

Learning Objectives

- List the various types of microorganisms and describe their defining characteristics

- Give examples of different types of cellular and viral microorganisms and infectious agents

- Describe the similarities and differences between archaea and bacteria

- Provide an overview of the field of microbiology

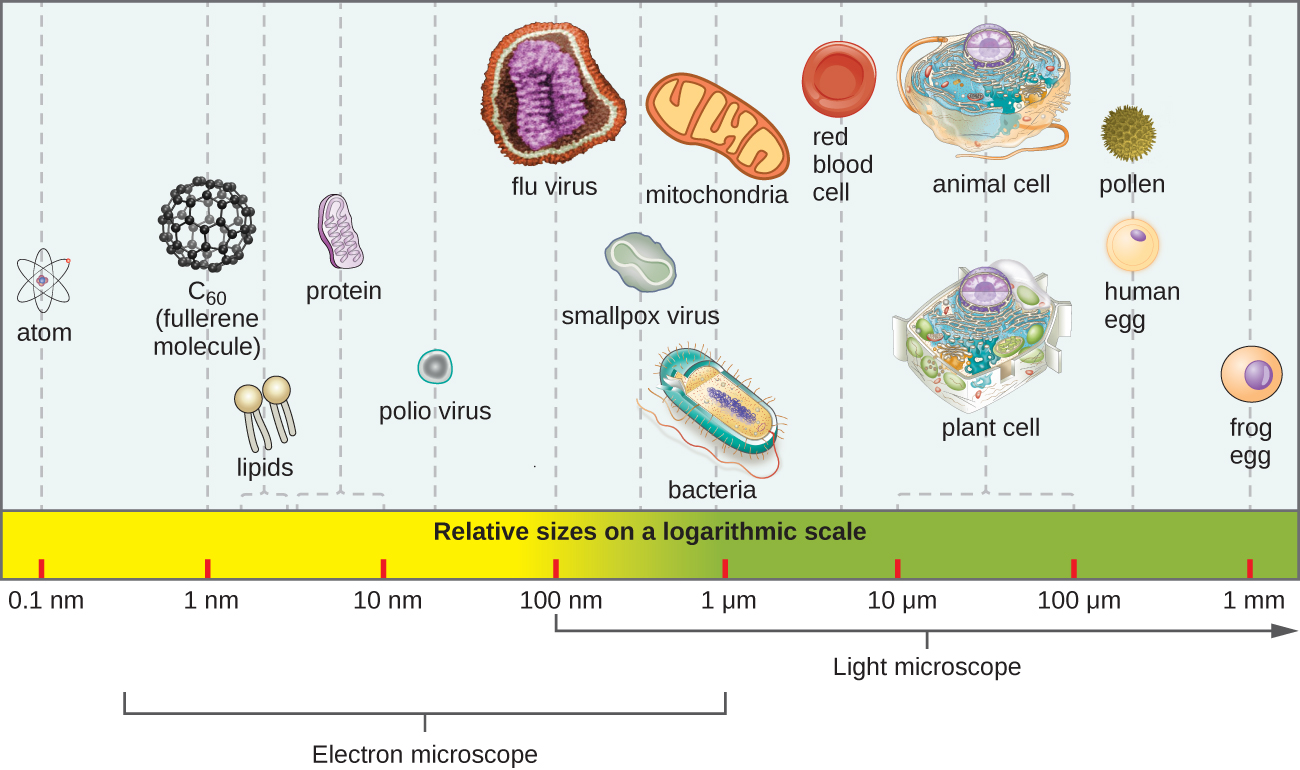

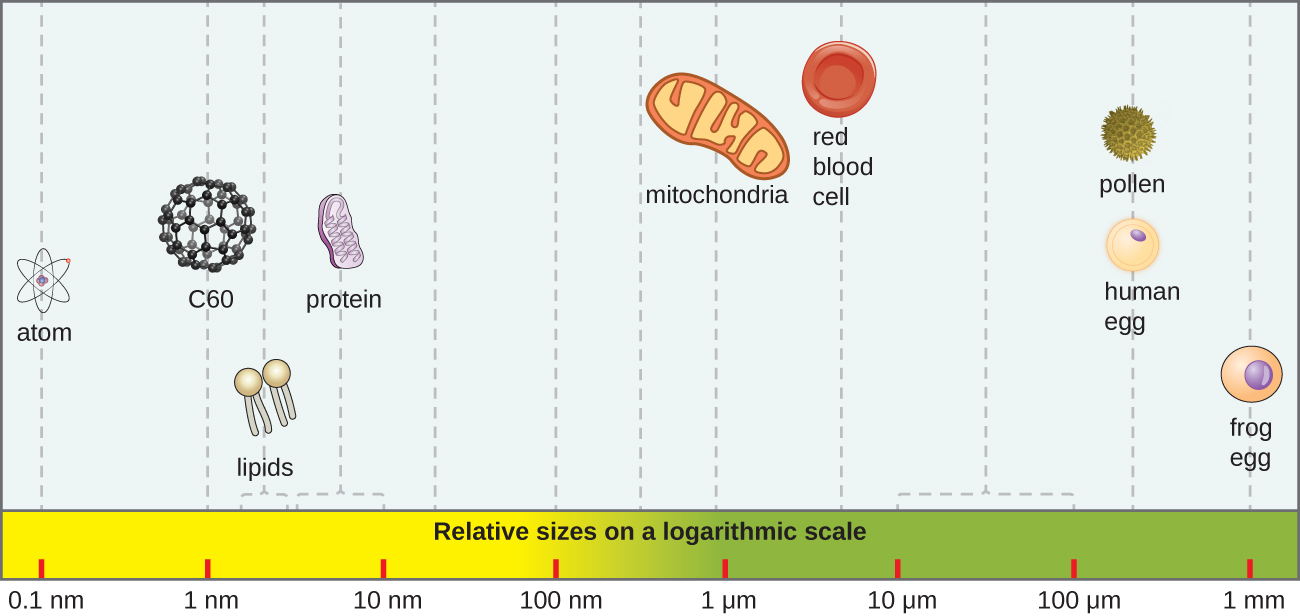

Most microbes are unicellular and small enough that they require artificial magnification to be seen. However, there are some unicellular microbes that are visible to the naked eye, and some multicellular organisms that are microscopic. An object must measure about 100 micrometers (µm) to be visible without a microscope, but most microorganisms are many times smaller than that. For some perspective, consider that a typical animal cell measures roughly 10 µm across but is still microscopic. Bacterial cells are typically about 1 µm, and viruses can be 10 times smaller than bacteria (Figure 1.14). See Table 1 for units of length used in microbiology.

Table 1.1

| Units of Length Commonly Used in Microbiology | ||

|---|---|---|

| Metric Unit | Meaning of Prefix | Metric Equivalent |

| meter (m) | — | 1 m = 100 m |

| decimeter (dm) | 1/10 | 1 dm = 0.1 m = 10−1 m |

| centimetre (cm) | 1/100 | 1 cm = 0.01 m = 10−2 m |

| millimetre (mm) | 1/1000 | 1 mm = 0.001 m = 10−3 m |

| micrometer (μm) | 1/1,000,000 | 1 μm = 0.000001 m = 10−6 m |

| nanometer (nm) | 1/1,000,000,000 | 1 nm = 0.000000001 m = 10−9 m |

Microorganisms differ from each other not only in size, but also in structure, habitat, metabolism, and many other characteristics. While we typically think of microorganisms as being unicellular, there are also many multicellular organisms that are too small to be seen without a microscope. Some microbes, such as viruses, are even acellular (not composed of cells).

Microorganisms are found in each of the three domains of life: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya. Microbes within the domains Bacteria and Archaea are all prokaryotes (their cells lack a nucleus), whereas microbes in the domain Eukarya are eukaryotes (their cells have a nucleus). Some microorganisms, such as viruses, do not fall within any of the three domains of life. In this section, we will briefly introduce each of the broad groups of microbes. Later chapters will go into greater depth about the diverse species within each group.

How big is a bacterium or a virus compared to other objects? Check out this interactive website to get a feel for the scale of different microorganisms.

Prokaryotic Microorganisms

Bacteria

Bacteria are found in nearly every habitat on earth, including within and on humans. Most bacteria are harmless or helpful, but some are pathogens, causing disease in humans and other animals. Bacteria are prokaryotic because their genetic material (DNA) is not housed within a true nucleus. Most bacteria have cell walls that contain peptidoglycan.

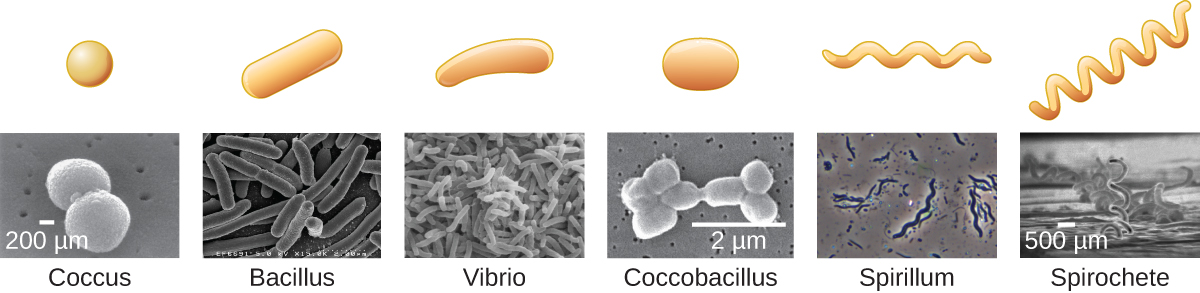

Bacteria are often described in terms of their general shape. Common shapes include spherical (coccus), rod-shaped (bacillus), or curved (spirillum, spirochete, or vibrio). Figure 1.15 shows examples of these shapes.

They have a wide range of metabolic capabilities and can grow in a variety of environments, using different combinations of nutrients. Some bacteria are photosynthetic, such as oxygenic cyanobacteria and anoxygenic green sulphur and green nonsulphur bacteria; these bacteria use energy derived from sunlight, and fix carbon dioxide for growth. Other types of bacteria are nonphotosynthetic, obtaining their energy from organic or inorganic compounds in their environment.

Archaea

Archaea are also unicellular prokaryotic organisms. Archaea and bacteria have different evolutionary histories, as well as significant differences in genetics, metabolic pathways, and the composition of their cell walls and membranes. Unlike most bacteria, archaeal cell walls do not contain peptidoglycan, but their cell walls are often composed of a similar substance called pseudopeptidoglycan. Like bacteria, archaea are found in nearly every habitat on earth, even extreme environments that are very cold, very hot, very basic, or very acidic (Figure 1.16). Some archaea live in the human body, but none have been shown to be human pathogens.

- What are the two main types of prokaryotic organisms?

- Name some of the defining characteristics of each type.

Eukaryotic Microorganisms

The domain Eukarya contains all eukaryotes, including uni- or multicellular eukaryotes such as protists, fungi, plants, and animals. The major defining characteristic of eukaryotes is that their cells contain a nucleus.

Protists

Protists are an informal grouping of eukaryotes that are not plants, animals, or fungi. Algae and protozoa are examples of protists.

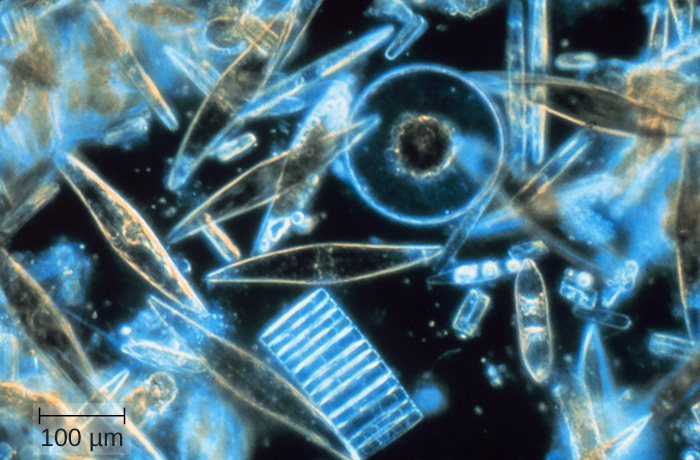

Algae (singular: alga) are protists that can be either unicellular or multicellular and vary widely in size, appearance, and habitat (Figure 1.17). Their cells are surrounded by cell walls made of cellulose, a type of carbohydrate. Algae are photosynthetic organisms that extract energy from the sun and release oxygen and carbohydrates into their environment. Because other organisms can use their waste products for energy, algae are important parts of many ecosystems. Many consumer products contain ingredients derived from algae, such as carrageenan or alginic acid, which are found in some brands of ice cream, salad dressing, beverages, lipstick, and toothpaste. A derivative of algae also plays a prominent role in the microbiology laboratory. Agar, a polysaccharide gel derived from algae, can be mixed with various nutrients and used to grow microorganisms in a Petri dish. Algae are also being developed as a possible source for biofuels.

Protozoa (singular: protozoan) are protists that make up the backbone of many food webs by providing nutrients for other organisms. Protozoa are very diverse. Some protozoa move with help from hair-like structures called cilia or whip-like structures called flagella. Others extend part of their cell membrane and cytoplasm to propel themselves forward. These cytoplasmic extensions are called pseudopods (“false feet”). Some protozoa are photosynthetic; others feed on organic material. Some are free-living, whereas others are parasitic, only able to survive by extracting nutrients from a host organism. Most protozoa are harmless, but some are pathogens that can cause disease in animals or humans (Figure 1.18).

Fungi

Fungi (singular: fungus) are also eukaryotes. Some multicellular fungi, such as mushrooms, resemble plants, but they are actually quite different. Fungi are not photosynthetic, and their cell walls are usually made out of chitin rather than cellulose.

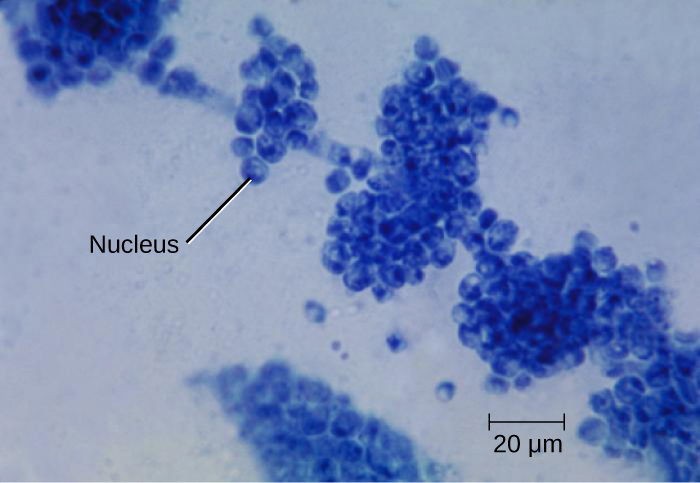

Unicellular fungi—yeasts—are included within the study of microbiology. There are more than 1000 known species. Yeasts are found in many different environments, from the deep sea to the human navel. Some yeasts have beneficial uses, such as causing bread to rise and beverages to ferment; but yeasts can also cause food to spoil. Some even cause diseases, such as vaginal yeast infections and oral thrush (Figure 1.19).

Other fungi of interest to microbiologists are multicellular organisms called moulds. Moulds are made up of long filaments that form visible colonies (Figure 1.20). Moulds are found in many different environments, from soil to rotting food to dank bathroom corners. Moulds play a critical role in the decomposition of dead plants and animals. Some moulds can cause allergies, and others produce disease-causing metabolites called mycotoxins. Moulds have been used to make pharmaceuticals, including penicillin, which is one of the most commonly prescribed antibiotics, and cyclosporine, used to prevent organ rejection following a transplant.

Name two types of protists and two types of fungi.

Name some of the defining characteristics of each type.

Viruses

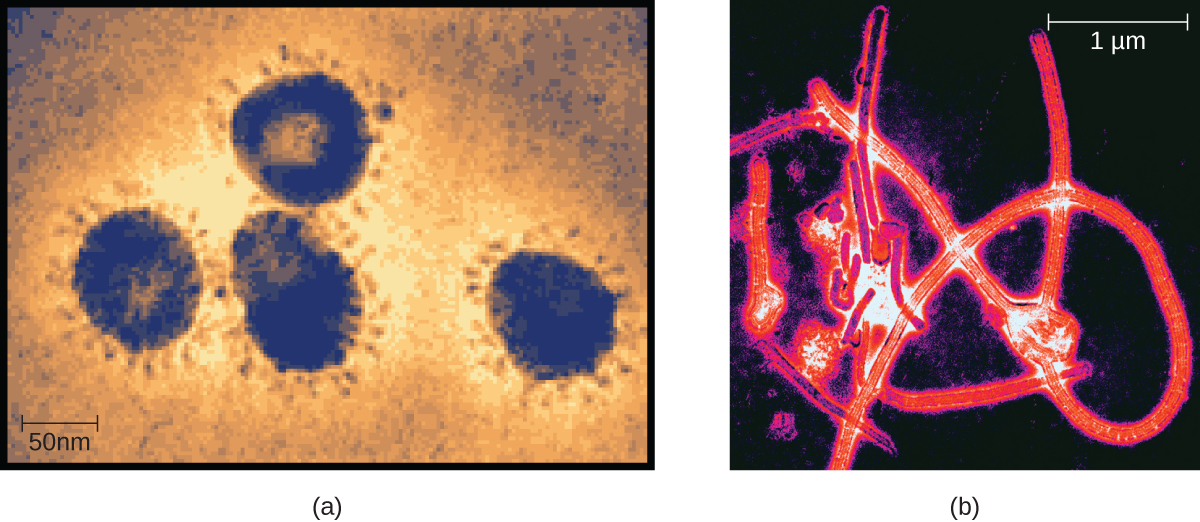

Viruses are acellular microorganisms, which means they are not composed of cells. Essentially, a virus consists of proteins and genetic material—either DNA or RNA, but never both—that are inert outside of a host organism. However, by incorporating themselves into a host cell, viruses are able to co-opt the host’s cellular mechanisms to multiply and infect other hosts.

Viruses can infect all types of cells, from human cells to the cells of other microorganisms. In humans, viruses are responsible for numerous diseases, from the common cold to deadly Ebola (Figure 1.21). However, many viruses do not cause disease.

- How are viruses different from other microorganisms?

Microbiology as a Field of Study

Microbiology is a broad term that encompasses the study of all different types of microorganisms. Until relatively recently, microbiologists tended to specialize in one of several subfields. For example, bacteriology is the study of bacteria; mycology is the study of fungi; protozoology is the study of protozoa; and virology is the study of viruses (Figure1.22). Immunology, the study of the immune system, is often included in the study of microbiology because host–pathogen interactions are central to our understanding of infectious disease processes. Microbiologists can also specialize in certain areas of microbiology, such as clinical microbiology, microbial ecology, applied microbiology, or food microbiology. Research in microbiology is becoming increasingly interdisciplinary. In fact, the more ground-breaking research papers typically involve authors from different academic departments, if not institutions, and in addition to the microbiologists, may include statisticians, computer scientists, engineers, bioinformaticists, biophysicists, chemists, biochemists and geochemists to name a few. It’s a very exciting time to be a microbiologist!

EYE ON ETHICS: Bioethics in Microbiology

In the 1940s, the U.S. government was looking for a solution to a medical problem: the prevalence of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) among soldiers. Several now-infamous government-funded studies used human subjects to research common STDs and treatments. In one such study, American researchers intentionally exposed more than 1300 human subjects in Guatemala to syphilis, gonorrhoea, and chancroid to determine the ability of penicillin and other antibiotics to combat these diseases. Subjects of the study included Guatemalan soldiers, prisoners, prostitutes, and psychiatric patients—none of whom were informed that they were taking part in the study. Researchers exposed subjects to STDs by various methods, from facilitating intercourse with infected prostitutes to inoculating subjects with the bacteria known to cause the diseases. This latter method involved making a small wound on the subject’s genitals or elsewhere on the body, and then putting bacteria directly into the wound.[1] In 2011, a U.S. government commission tasked with investigating the experiment revealed that only some of the subjects were treated with penicillin, and 83 subjects died by 1953, likely as a result of the study.[2]

Unfortunately, this is one of many horrific examples of microbiology experiments that have violated basic ethical standards. Even if this study had led to a life-saving medical breakthrough (it did not), few would argue that its methods were ethically sound or morally justifiable. But not every case is so clear cut. Professionals working in clinical settings are frequently confronted with ethical dilemmas, such as working with patients who decline a vaccine or life-saving blood transfusion. These are just two examples of life-and-death decisions that may intersect with the religious and philosophical beliefs of both the patient and the health-care professional.

No matter how noble the goal, microbiology studies and clinical practice must be guided by a certain set of ethical principles. Studies must be done with integrity. Patients and research subjects provide informed consent (not only agreeing to be treated or studied but demonstrating an understanding of the purpose of the study and any risks involved). Patients’ rights must be respected. Procedures must be approved by an institutional review board. When working with patients, accurate record-keeping, honest communication, and confidentiality are paramount. Animals used for research must be treated humanely, and all protocols must be approved by an institutional animal care and use committee. These are just a few of the ethical principles explored in the Eye on Ethics boxes throughout this book.

CLINICAL FOCUS: Resolution

Cora’s CSF samples show no signs of inflammation or infection, as would be expected with a viral infection. However, there is a high concentration of a particular protein, 14-3-3 protein, in her CSF. An electroencephalogram (EEG) of her brain function is also abnormal. The EEG resembles that of a patient with a neurodegenerative disease like Alzheimer’s or Huntington’s, but Cora’s rapid cognitive decline is not consistent with either of these. Instead, her doctor concludes that Cora has Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (CJD), a type of transmissible spongiform encephalopathy (TSE).

CJD is an extremely rare disease, with only about 300 cases in the United States each year. It is not caused by a bacterium, fungus, or virus, but rather by prions—which do not fit neatly into any particular category of microbe. Like viruses, prions are not found on the tree of life because they are acellular. Prions are extremely small, about one-tenth the size of a typical virus. They contain no genetic material and are composed solely of a type of abnormal protein.

CJD can have several different causes. It can be acquired through exposure to the brain or nervous-system tissue of an infected person or animal. Consuming meat from an infected animal is one way such exposure can occur. There have also been rare cases of exposure to CJD through contact with contaminated surgical equipment[3] and from cornea and growth-hormone donors who unknowingly had CJD.[4][5] In rare cases, the disease results from a specific genetic mutation that can sometimes be hereditary. However, in approximately 85% of patients with CJD, the cause of the disease is spontaneous (or sporadic) and has no identifiable cause.[6] Based on her symptoms and their rapid progression, Cora is diagnosed with sporadic CJD.

Unfortunately for Cora, CJD is a fatal disease for which there is no approved treatment. Approximately 90% of patients die within 1 year of diagnosis.[7] Her doctors focus on limiting her pain and cognitive symptoms as her disease progresses. Eight months later, Cora dies. Her CJD diagnosis is confirmed with a brain autopsy.

Go back to the previous Clinical Focus box.

Key Takeaways

- Microorganisms are very diverse and are found in all three domains of life: Archaea, Bacteria, and Eukarya.

- Archaea and bacteria are classified as prokaryotes because they lack a cellular nucleus. Archaea differ from bacteria in evolutionary history, genetics, metabolic pathways, and cell wall and membrane composition.

- Archaea inhabit nearly every environment on earth, but no archaea have been identified as human pathogens.

- Eukaryotes studied in microbiology include algae, protozoa, fungi, and helminths.

- Algae are plant-like organisms that can be either unicellular or multicellular, and derive energy via photosynthesis.

- Protozoa are unicellular organisms with complex cell structures; most are motile.

- Microscopic fungi include moulds and yeasts.

- Viruses are acellular microorganisms that require a host to reproduce.

- The field of microbiology is extremely broad. Microbiologists typically specialize in one of many subfields, but all health professionals need a solid foundation in clinical microbiology.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blanks

Short Answer

- Describe the differences between bacteria and archaea.

- Name three structures that various protozoa use for locomotion.

- Describe the actual and relative sizes of a virus, a bacterium, and a plant or animal cell.

Critical Thinking

- Contrast the behaviour of a virus outside versus inside a cell.

- Where would a virus, bacterium, animal cell, and a prion belong on this chart?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_sizes

- microbiology sign © Nick Youngson

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_bacteria

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_archaea

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_algae

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_giardia

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_yeast

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_mold

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_virus

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_atwork

- OSC_Microbio_01_03_ArtConnect_img

- Kara Rogers. “Guatemala Syphilis Experiment: American Medical Research Project”. Encylopaedia Britannica. http://www.britannica.com/event/Guatemala-syphilis-experiment. Accessed May 12, 2019. ↵

- Susan Donaldson James. “Syphilis Experiments Shock, But So Do Third-World Drug Trials.” ABC World News. August 30, 2011. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/guatemala-syphilis-experiments-shock-us-drug-trials-exploit/story?id=14414902. Accessed May 12, 2019. ↵

- Greg Botelho. “Case of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Confirmed in New Hampshire.” CNN. 2013. http://www.cnn.com/2013/09/20/health/creutzfeldt-jakob-brain-disease/. ↵

- P. Rudge et al. “Iatrogenic CJD Due to Pituitary-Derived Growth Hormone With Genetically Determined Incubation Times of Up to 40 Years.” Brain 138 no. 11 (2015): 3386–3399. ↵

- J.G. Heckmann et al. “Transmission of Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease via a Corneal Transplant.” Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry 63 no. 3 (1997): 388–390. ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. “Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Fact Sheet.” NIH. 2015. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/cjd/detail_cjd.htm#288133058. ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. “Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Fact Sheet.” NIH. 2015. http://www.ninds.nih.gov/disorders/cjd/detail_cjd.htm#288133058. Accessed June 22, 2015. ↵