19. Adaptive Specific Host Defenses

19.1 Overview of Specific Adaptive Immunity

Learning Objectives

- Define memory, primary response, secondary response, and specificity

- Distinguish between humoral and cellular immunity

- Differentiate between antigens, epitopes, and haptens

- Describe the structure and function of antibodies and distinguish between the different classes of antibodies

CLINICAL FOCUS: Part 1

Olivia, a one-year old infant, is brought to the emergency room by her parents, who report her symptoms: excessive crying, irritability, sensitivity to light, unusual lethargy, and vomiting. A physician feels swollen lymph nodes in Olivia’s throat and armpits. In addition, the area of the abdomen over the spleen is swollen and tender.

- What do these symptoms suggest?

- What tests might be ordered to try to diagnose the problem?

Jump to the next Clinical Focus box.

Adaptive immunity is defined by two important characteristics: specificity and memory. Specificity refers to the adaptive immune system’s ability to target specific pathogens, and memory refers to its ability to quickly respond to pathogens to which it has previously been exposed. For example, when an individual recovers from chickenpox, the body develops a memory of the infection that will specifically protect it from the causative agent, the varicella-zoster virus, if it is exposed to the virus again later.

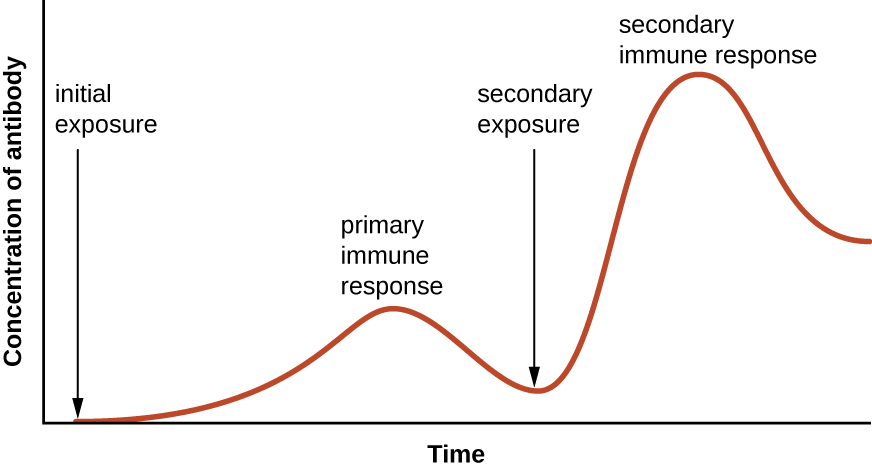

Specificity and memory are achieved by essentially programming certain cells involved in the immune response to respond rapidly to subsequent exposures of the pathogen. This programming occurs as a result of the first exposure to a pathogen or vaccine, which triggers a primary response. Subsequent exposures result in a secondary response that is faster and stronger as a result of the body’s memory of the first exposure (Figure 19.2). This secondary response, however, is specific to the pathogen in question. For example, exposure to one virus (e.g., varicella-zoster virus) will not provide protection against other viral diseases (e.g., measles, mumps, or polio).

Adaptive specific immunity involves the actions of two distinct cell types: B lymphocytes (B cells) and T lymphocytes (T cells). Although B cells and T cells arise from a common hematopoietic stem cell differentiation pathway (see Fig. 18.12), their sites of maturation and their roles in adaptive immunity are very different.

B cells mature in the bone marrow and are responsible for the production of glycoproteins called antibodies, or immunoglobulins. Antibodies are involved in the body’s defence against pathogens and toxins in the extracellular environment. Mechanisms of adaptive specific immunity that involve B cells and antibody production are referred to as humoral immunity. The maturation of T cells occurs in the thymus. T cells function as the central orchestrator of both innate and adaptive immune responses. They are also responsible for destruction of cells infected with intracellular pathogens. The targeting and destruction of intracellular pathogens by T cells is called cell-mediated immunity, or cellular immunity.

- List the two defining characteristics of adaptive immunity.

- Explain the difference between a primary and secondary immune response.

- How do humoral and cellular immunity differ?

Antigens

Activation of the adaptive immune defences is triggered by pathogen-specific molecular structures called antigens. Antigens are similar to the pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) discussed in Pathogen Recognition and Phagocytosis; however, whereas PAMPs are molecular structures found on numerous pathogens, antigens are unique to a specific pathogen. The antigens that stimulate adaptive immunity to chickenpox, for example, are unique to the varicella-zoster virus but significantly different from the antigens associated with other viral pathogens.

The term antigen was initially used to describe molecules that stimulate the production of antibodies; in fact, the term comes from a combination of the words antibody and generator, and a molecule that stimulates antibody production is said to be antigenic. However, the role of antigens is not limited to humoral immunity and the production of antibodies; antigens also play an essential role in stimulating cellular immunity, and for this reason antigens are sometimes more accurately referred to as immunogens. In this text, however, we will typically refer to them as antigens.

Pathogens possess a variety of structures that may contain antigens. For example, antigens from bacterial cells may be associated with their capsules, cell walls, fimbriae, flagella, or pili. Bacterial antigens may also be associated with extracellular toxins and enzymes that they secrete. Viruses possess a variety of antigens associated with their capsids, envelopes, and the spike structures they use for attachment to cells.

Antigens may belong to any number of molecular classes, including carbohydrates, lipids, nucleic acids, proteins, and combinations of these molecules. Antigens of different classes vary in their ability to stimulate adaptive immune defences as well as in the type of response they stimulate (humoral or cellular). The structural complexity of an antigenic molecule is an important factor in its antigenic potential. In general, more complex molecules are more effective as antigens. For example, the three-dimensional complex structure of proteins make them the most effective and potent antigens, capable of stimulating both humoral and cellular immunity. In comparison, carbohydrates are less complex in structure and therefore less effective as antigens; they can only stimulate humoral immune defences. Lipids and nucleic acids are the least antigenic molecules, and in some cases may only become antigenic when combined with proteins or carbohydrates to form glycolipids, lipoproteins, or nucleoproteins.

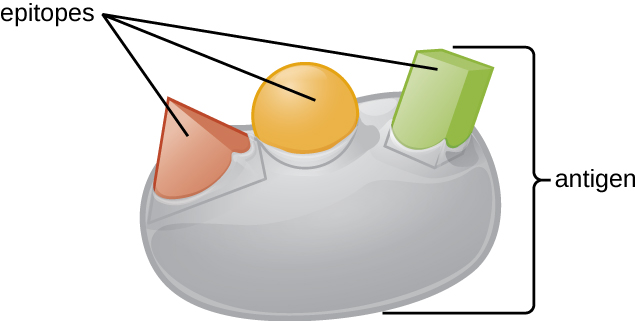

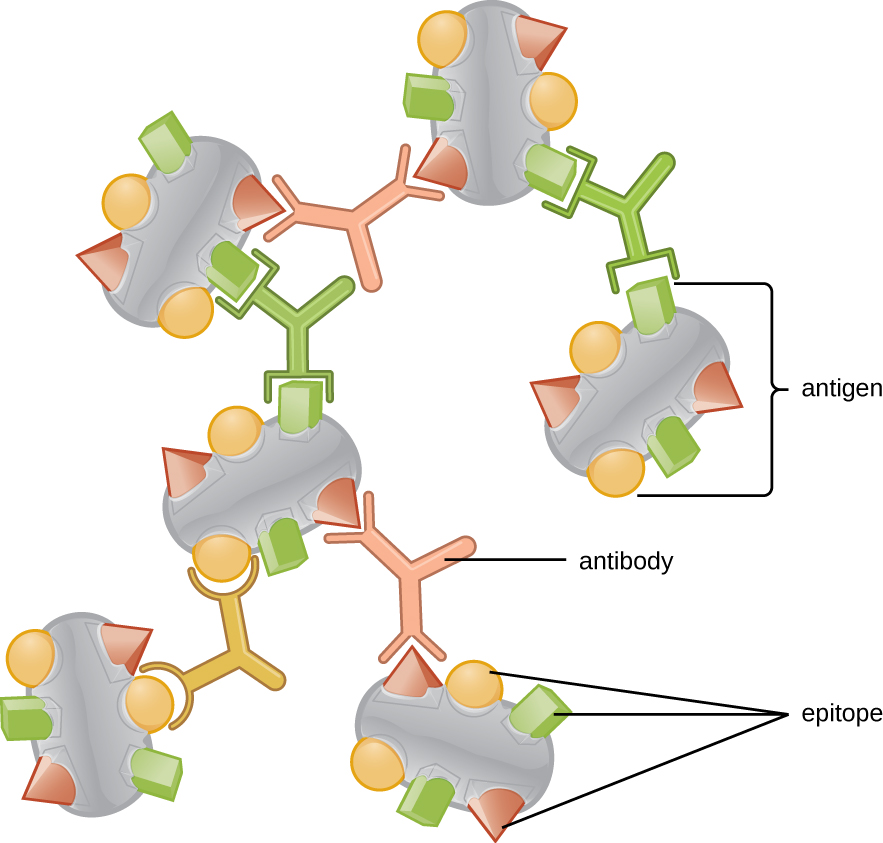

One reason the three-dimensional complexity of antigens is so important is that antibodies and T cells do not recognize and interact with an entire antigen but with smaller exposed regions on the surface of antigens called epitopes. A single antigen may possess several different epitopes (Figure 19.3), and different antibodies may bind to different epitopes on the same antigen (Figure 19.4). For example, the bacterial flagellum is a large, complex protein structure that can possess hundreds or even thousands of epitopes with unique three-dimensional structures. Moreover, flagella from different bacterial species (or even strains of the same species) contain unique epitopes that can only be bound by specific antibodies.

An antigen’s size is another important factor in its antigenic potential. Whereas large antigenic structures like flagella possess multiple epitopes, some molecules are too small to be antigenic by themselves. Such molecules, called haptens, are essentially free epitopes that are not part of the complex three-dimensional structure of a larger antigen. For a hapten to become antigenic, it must first attach to a larger carrier molecule (usually a protein) to produce a conjugate antigen. The hapten-specific antibodies produced in response to the conjugate antigen are then able to interact with unconjugated free hapten molecules. Haptens are not known to be associated with any specific pathogens, but they are responsible for some allergic responses. For example, the hapten urushiol, a molecule found in the oil of plants that cause poison ivy, causes an immune response that can result in a severe rash (called contact dermatitis). Similarly, the hapten penicillin can cause allergic reactions to drugs in the penicillin class.

- What is the difference between an antigen and an epitope?

- What factors affect an antigen’s antigenic potential?

- Why are haptens typically not antigenic, and how do they become antigenic?

Antibodies

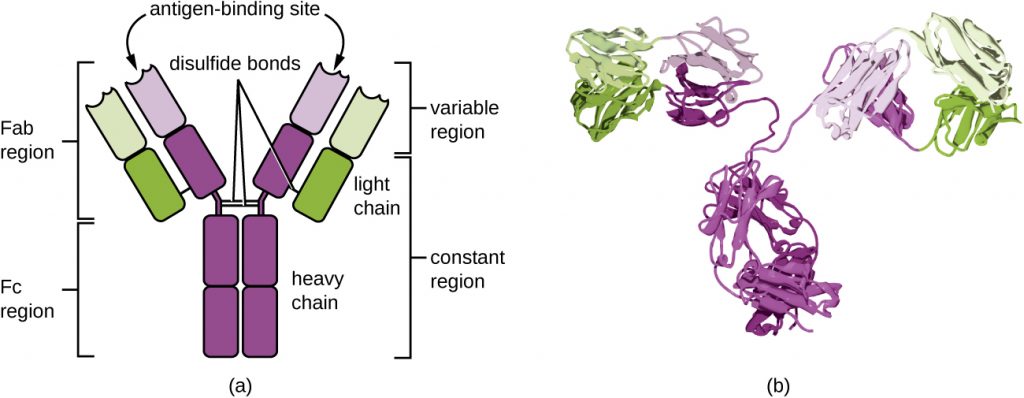

Antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) are glycoproteins that are present in both the blood and tissue fluids. The basic structure of an antibody monomer consists of four protein chains held together by disulphide bonds (Figure 19.5). A disulphide bond is a covalent bond between the sulfhydryl R groups found on two cysteine amino acids. The two largest chains are identical to each other and are called the heavy chains. The two smaller chains are also identical to each other and are called the light chains. Joined together, the heavy and light chains form a basic Y-shaped structure.

The two ‘arms’ of the Y-shaped antibody molecule are known as the Fab region, for “fragment of antigen binding.” The far end of the Fab region is the variable region, which serves as the site of antigen binding. The amino acid sequence in the variable region dictates the three-dimensional structure, and thus the specific three-dimensional epitope to which the Fab region is capable of binding. Although the epitope specificity of the Fab regions is identical for each arm of a single antibody molecule, this region displays a high degree of variability between antibodies with different epitope specificities. Binding to the Fab region is necessary for neutralization of pathogens, agglutination or aggregation of pathogens, and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

The constant region of the antibody molecule includes the trunk of the Y and lower portion of each arm of the Y. The trunk of the Y is also called the Fc region, for “fragment of crystallization,” and is the site of complement factor binding and binding to phagocytic cells during antibody-mediated opsonization.

- Describe the different functions of the Fab region and the Fc region.

Antibody Classes

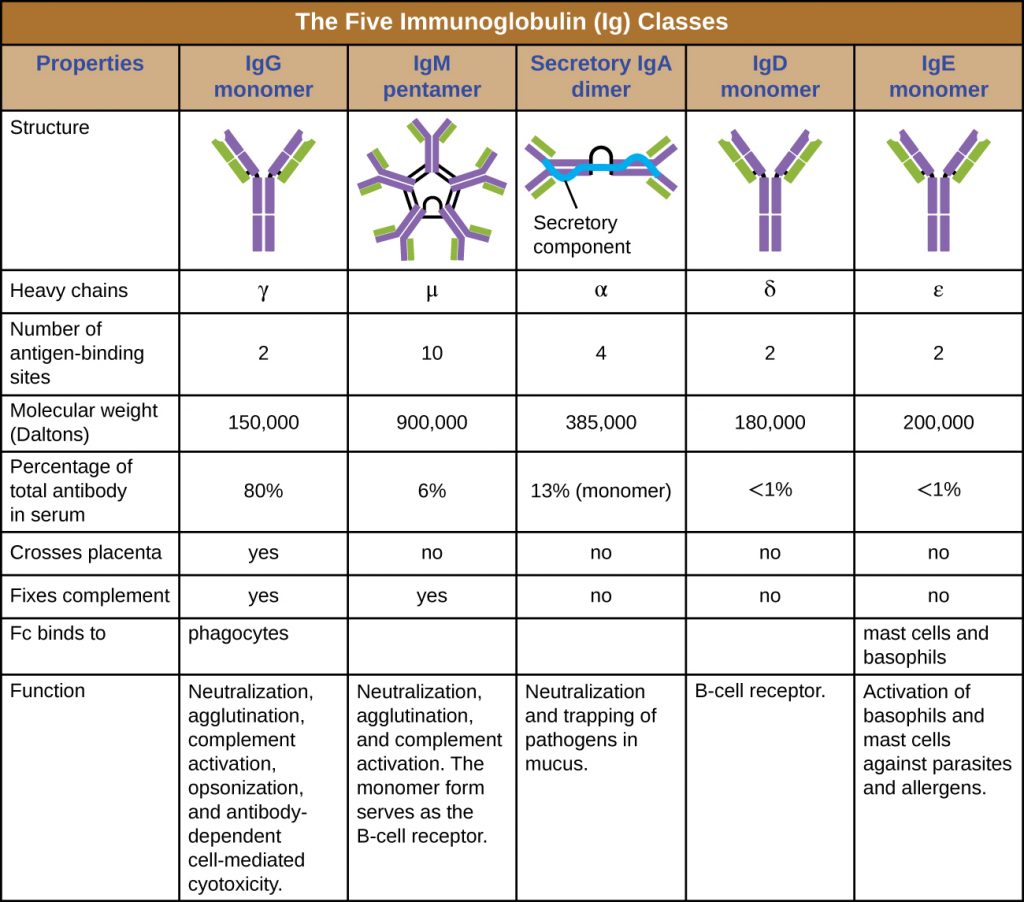

The constant region of an antibody molecule determines its class, or isotype. The five classes of antibodies are IgG, IgM, IgA, IgD, and IgE. Each class possesses unique heavy chains designated by Greek letters γ, μ, α, δ, and ε, respectively. Antibody classes also exhibit important differences in abundance in serum, arrangement, body sites of action, functional roles, and size (Figure 19.6).

IgG is a monomer that is by far the most abundant antibody in human blood, accounting for about 80% of total serum antibody. IgG penetrates efficiently into tissue spaces, and is the only antibody class with the ability to cross the placental barrier, providing passive immunity to the developing fetus during pregnancy. IgG is also the most versatile antibody class in terms of its role in the body’s defence against pathogens.

IgM is initially produced in a monomeric membrane-bound form that serves as an antigen-binding receptor on B cells. The secreted form of IgM assembles into a pentamer with five monomers of IgM bound together by a protein structure called the J chain. Although the location of the J chain relative to the Fc regions of the five monomers prevents IgM from performing some of the functions of IgG, the ten available Fab sites associated with a pentameric IgM make it an important antibody in the body’s arsenal of defences. IgM is the first antibody produced and secreted by B cells during the primary and secondary immune responses, making pathogen-specific IgM a valuable diagnostic marker during active or recent infections.

IgA accounts for about 13% of total serum antibody, and secretory IgA is the most common and abundant antibody class found in the mucus secretions that protect the mucous membranes. IgA can also be found in other secretions such as breast milk, tears, and saliva. Secretory IgA is assembled into a dimeric form with two monomers joined by a protein structure called the secretory component. One of the important functions of secretory IgA is to trap pathogens in mucus so that they can later be eliminated from the body.

Similar to IgM, IgD is a membrane-bound monomer found on the surface of B cells, where it serves as an antigen-binding receptor. However, IgD is not secreted by B cells, and only trace amounts are detected in serum. These trace amounts most likely come from the degradation of old B cells and the release of IgD molecules from their cytoplasmic membranes.

IgE is the least abundant antibody class in serum. Like IgG, it is secreted as a monomer, but its role in adaptive immunity is restricted to anti-parasitic defences. The Fc region of IgE binds to basophils and mast cells. The Fab region of the bound IgE then interacts with specific antigen epitopes, causing the cells to release potent pro-inflammatory mediators. The inflammatory reaction resulting from the activation of mast cells and basophils aids in the defence against parasites, but this reaction is also central to allergic reactions (see Diseases of the Immune System).

- What part of an antibody molecule determines its class?

- What class of antibody is involved in protection against parasites?

- Describe the difference in structure between IgM and IgG.

Antigen-Antibody Interactions

Different classes of antibody play important roles in the body’s defence against pathogens. These functions include neutralization of pathogens, opsonization for phagocytosis, agglutination, complement activation, and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity. For most of these functions, antibodies also provide an important link between adaptive specific immunity and innate nonspecific immunity.

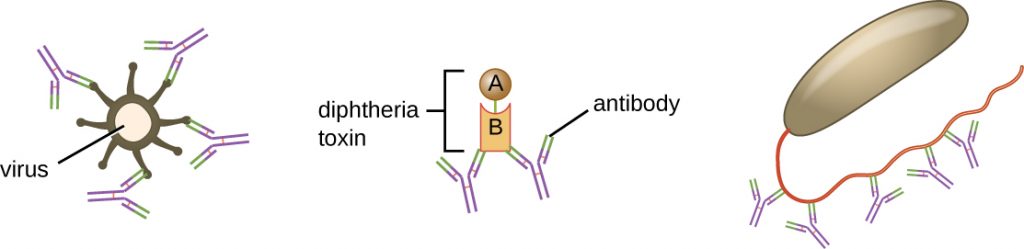

Neutralization involves the binding of certain antibodies (IgG, IgM, or IgA) to epitopes on the surface of pathogens or toxins, preventing their attachment to cells. For example, Secretory IgA can bind to specific pathogens and block initial attachment to intestinal mucosal cells. Similarly, specific antibodies can bind to certain toxins, blocking them from attaching to target cells and thus neutralizing their toxic effects. Viruses can be neutralized and prevented from infecting a cell by the same mechanism (Figure 19.7).

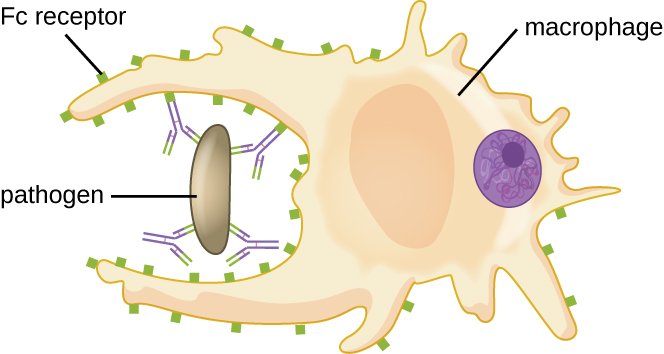

As described in Chemical Defences, opsonization is the coating of a pathogen with molecules, such as complement factors, C-reactive protein, and serum amyloid A, to assist in phagocyte binding to facilitate phagocytosis. IgG antibodies also serve as excellent opsonins, binding their Fab sites to specific epitopes on the surface of pathogens. Phagocytic cells such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils have receptors on their surfaces that recognize and bind to the Fc portion of the IgG molecules; thus, IgG helps such phagocytes attach to and engulf the pathogens they have bound (Figure 19.8).

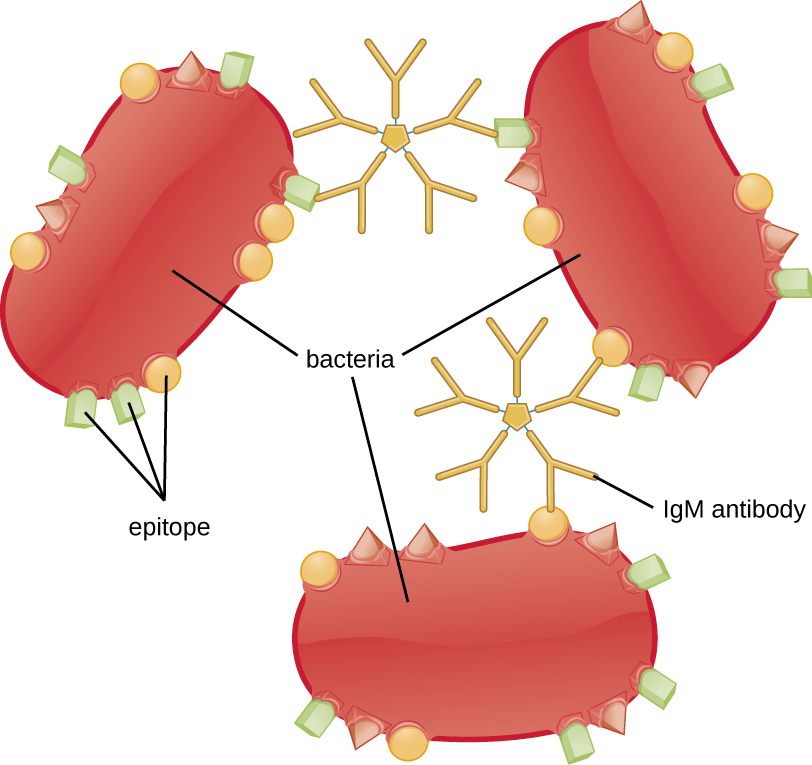

Agglutination or aggregation involves the cross-linking of pathogens by antibodies to create large aggregates (Figure 19.9). IgG has two Fab antigen-binding sites, which can bind to two separate pathogen cells, clumping them together. When multiple IgG antibodies are involved, large aggregates can develop; these aggregates are easier for the kidneys and spleen to filter from the blood and easier for phagocytes to ingest for destruction. The pentameric structure of IgM provides ten Fab binding sites per molecule, making it the most efficient antibody for agglutination.

Another important function of antibodies is activation of the complement cascade. As discussed in the previous chapter, the complement system is an important component of the innate defences, promoting the inflammatory response, recruiting phagocytes to site of infection, enhancing phagocytosis by opsonization, and killing gram-negative bacterial pathogens with the membrane attack complex (MAC). Complement activation can occur through three different pathways (see Fig. 18.9), but the most efficient is the classical pathway, which requires the initial binding of IgG or IgM antibodies to the surface of a pathogen cell, allowing for recruitment and activation of the C1 complex.

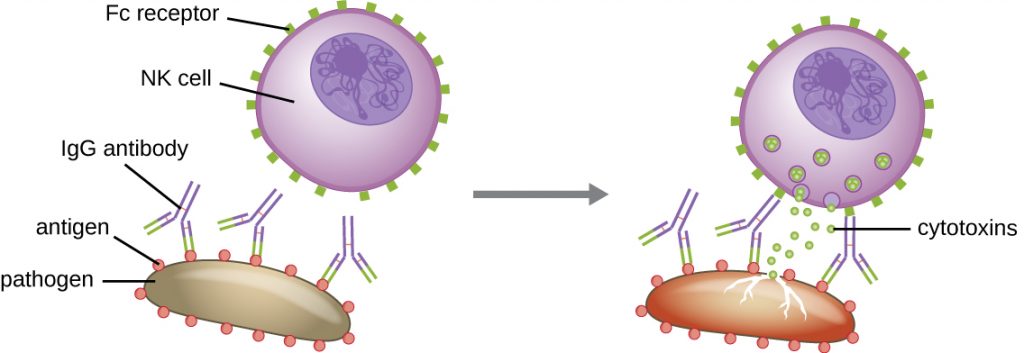

Yet another important function of antibodies is antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC), which enhances killing of pathogens that are too large to be phagocytosed. This process is best characterized for natural killer cells (NK cells), as shown in Figure 19.10, but it can also involve macrophages and eosinophils. ADCC occurs when the Fab region of an IgG antibody binds to a large pathogen; Fc receptors on effector cells (e.g., NK cells) then bind to the Fc region of the antibody, bringing them into close proximity with the target pathogen. The effector cell then secretes powerful cytotoxins (e.g., perforin and granzymes) that kill the pathogen.

- Where is IgA normally found?

- Which class of antibody crosses the placenta, providing protection to the fetus?

- Compare the mechanisms of opsonization and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Key Takeaways

- Adaptive immunity is an acquired defence against foreign pathogens that is characterized by specificity and memory. The first exposure to an antigen stimulates a primary response, and subsequent exposures stimulate a faster and strong secondary response.

- Adaptive immunity is a dual system involving humoral immunity (antibodies produced by B cells) and cellular immunity (T cells directed against intracellular pathogens).

- Antigens, also called immunogens, are molecules that activate adaptive immunity. A single antigen possesses smaller epitopes, each capable of inducing a specific adaptive immune response.

- An antigen’s ability to stimulate an immune response depends on several factors, including its molecular class, molecular complexity, and size.

- Antibodies (immunoglobulins) are Y-shaped glycoproteins with two Fab sites for binding antigens and an Fc portion involved in complement activation and opsonization.

- The five classes of antibody are IgM, IgG, IgA, IgE, and IgD, each differing in size, arrangement, location within the body, and function. The five primary functions of antibodies are neutralization, opsonization, agglutination, complement activation, and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity (ADCC).

Multiple Choice

Drag and Drop

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- What is the difference between humoral and cellular adaptive immunity?

- What is the difference between an antigen and a hapten?

- Describe the mechanism of antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity.

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_18_01_responses

- OSC_Microbio_18_02_epitope

- OSC_Microbio_18_02_antbind

- OSC_Microbio_18_04_ABstruct

- OSC_Microbio_18_04_ABClassTBL

- OSC_Microbio_18_04_neutral

- OSC_Microbio_18_04_opson

- OSC_Microbio_18_04_agg

- OSC_Microbio_18_04_NK