24. Urogenital System Infections

24.2 Bacterial Infections of the Urinary System

Learning Objectives

- Identify the most common bacterial pathogens that can cause urinary tract infections

- Compare the major characteristics of specific bacterial diseases affecting the urinary tract

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) include infections of the urethra, bladder, and kidneys, and are common causes of urethritis, cystitis, pyelonephritis, and glomerulonephritis. Bacteria are the most common causes of UTIs, especially in the urethra and bladder.

Cystitis

Cystitis is most often caused by a bacterial infection of the bladder, but it can also occur as a reaction to certain treatments or irritants such as radiation treatment, hygiene sprays, or spermicides. Common symptoms of cystitis include dysuria (urination accompanied by burning, discomfort, or pain), pyuria (pus in the urine), hematuria (blood in the urine), and bladder pain.

In women, bladder infections are more common because the urethra is short and located in close proximity to the anus, which can result in infections of the urinary tract by faecal bacteria. Bladder infections are also more common in the elderly because the bladder may not empty fully, causing urine to pool; the elderly may also have weaker immune systems that make them more vulnerable to infection. Conditions such as prostatitis in men or kidney stones in both men and women can impact proper drainage of urine and increase risk of bladder infections. Catheterization can also increase the risk of bladder infection (see Case in Point: Cystitis in the Elderly).

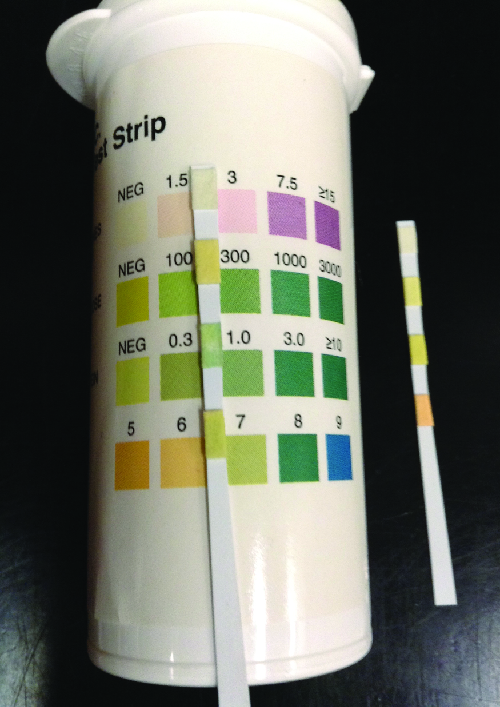

Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia coli (most commonly), Proteus vulgaris, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Klebsiella pneumoniae cause most bladder infections. Gram-positive pathogens associated with cystitis include the coagulase-negative Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Streptococcus agalactiae. Routine manual urinalysis using a urine dipstick or test strip can be used for rapid screening of infection. These test strips (Figure 24.5) are either held in a urine stream or dipped in a sample of urine to test for the presence of nitrites, leukocyte esterase, protein, or blood that can indicate an active bacterial infection. The presence of nitrite may indicate the presence of E. coli or K. pneumonia; these bacteria produce nitrate reductase, which converts nitrate to nitrite. The leukocyte esterase (LE) test detects the presence of neutrophils as an indication of active infection.

Low specificity, sensitivity, or both, associated with these rapid screening tests require that care be taken in interpretation of results and in their use in diagnosis of urinary tract infections. Therefore, positive LE or nitrite results are followed by a urine culture to confirm a bladder infection. Urine culture is generally accomplished using blood agar and MacConkey agar, and it is important to culture a clean catch of urine to minimize contamination with normal microbiota of the penis and vagina. A clean catch of urine is accomplished by first washing the labia and urethral opening of female patients or the penis of male patients. The patient then releases a small amount of urine into the toilet bowl before stopping the flow of urine. Finally, the patient resumes urination, this time filling the container used to collect the specimen.

Bacterial cystitis is commonly treated with fluoroquinolones, nitrofurantoin, cephalosporins, or a combination of trimethoprim and sulfamethoxazole. Pain medications may provide relief for patients with dysuria. Treatment is more difficult in elderly patients, who experience a higher rate of complications such as sepsis and kidney infections.

CASE IN POINT: Cystitis in the Elderly

Robert, an 81-year-old widower with early onset Alzheimer’s, was recently moved to a nursing home because he was having difficulty living on his own. Within a few weeks of his arrival, he developed a fever and began to experience pain associated with urination. He also began having episodes of confusion and delirium. The doctor assigned to examine Robert read his file and noticed that Robert was treated for prostatitis several years earlier. When he asked Robert how often he had been urinating, Robert explained that he had been trying not to drink too much so that he didn’t have to walk to the restroom.

All of this evidence suggests that Robert likely has a urinary tract infection. Robert’s age means that his immune system has probably begun to weaken, and his previous prostate condition may be making it difficult for him to empty his bladder. In addition, Robert’s avoidance of fluids has led to dehydration and infrequent urination, which may have allowed an infection to establish itself in his urinary tract. The fever and dysuria are common signs of a UTI in patients of all ages, and UTIs in elderly patients are often accompanied by a notable decline in mental function.

Physical challenges often discourage elderly individuals from urinating as frequently as they would otherwise. In addition, neurological conditions that disproportionately affect the elderly (e.g., Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease) may also reduce their ability to empty their bladders. Robert’s doctor noted that he was having difficulty navigating his new home and recommended that he be given more assistance and that his fluid intake be monitored. The doctor also took a urine sample and ordered a laboratory culture to confirm the identity of the causative agent.

- Why is it important to identify the causative agent in a UTI?

- Should the doctor prescribe a broad-spectrum or narrow-spectrum antibiotic to treat Robert’s UTI? Why?

Kidney Infections (Pyelonephritis and Glomerulonephritis)

Pyelonephritis, an inflammation of the kidney, can be caused by bacteria that have spread from other parts of the urinary tract (such as the bladder). In addition, pyelonephritis can develop from bacteria that travel through the bloodstream to the kidney. When the infection spreads from the lower urinary tract, the causative agents are typically faecal bacteria such as E. coli. Common signs and symptoms include back pain (due to the location of the kidneys), fever, and nausea or vomiting. Gross hematuria (visible blood in the urine) occurs in 30–40% of women but is rare in men.[1] The infection can become serious, potentially leading to bacteraemia and systemic effects that can become life-threatening. Scarring of the kidney can occur and persist after the infection has cleared, which may lead to dysfunction.

Diagnosis of pyelonephritis is made using microscopic examination of urine, culture of urine, testing for leukocyte esterase and nitrite levels, and examination of the urine for blood or protein. It is also important to use blood cultures to evaluate the spread of the pathogen into the bloodstream. Imaging of the kidneys may be performed in high-risk patients with diabetes or immunosuppression, the elderly, patients with previous renal damage, or to rule out an obstruction in the kidney. Pyelonephritis can be treated with either oral or intravenous antibiotics, including penicillins, cephalosporins, vancomycin, fluoroquinolones, carbapenems, and aminoglycosides.

Glomerulonephritis occurs when the glomeruli of the nephrons are damaged from inflammation. Whereas pyelonephritis is usually acute, glomerulonephritis may be acute or chronic. The most well-characterized mechanism of glomerulonephritis is the post-streptococcal sequelae associated with Streptococcus pyogenes throat and skin infections. Although S. pyogenes does not directly infect the glomeruli of the kidney, immune complexes that form in blood between S. pyogenes antigens and antibodies lodge in the capillary endothelial cell junctions of the glomeruli and trigger a damaging inflammatory response. Glomerulonephritis can also occur in patients with bacterial endocarditis (infection and inflammation of heart tissue); however, it is currently unknown whether glomerulonephritis associated with endocarditis is also immune-mediated.

Leptospirosis

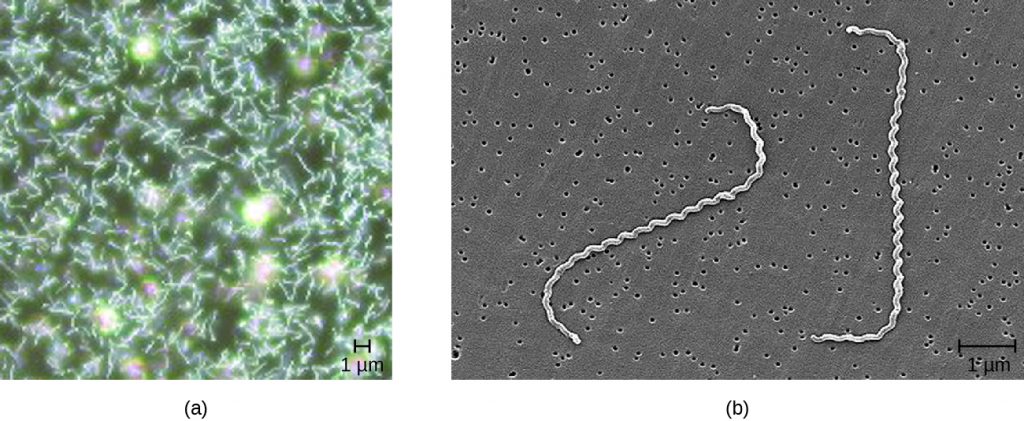

Leptospira are generally harmless spirochetes that are commonly found in the soil. However, some pathogenic species can cause an infection called leptospirosis in the kidneys and other organs (Figure 24.6). Leptospirosis can produce fever, headache, chills, vomiting, diarrhoea, and rash with severe muscular pain. If the disease continues to progress, infection of the kidney, meninges, or liver may occur and may lead to organ failure or meningitis. When the kidney and liver become seriously infected, it is called Weil’s disease. Pulmonary haemorrhagic syndrome can also develop in the lungs, and jaundice may occur.

Leptospira spp. are found widely in animals such as dogs, horses, cattle, pigs, and rodents, and are excreted in their urine. Humans generally become infected by coming in contact with contaminated soil or water, often while swimming or during flooding; infection can also occur through contact with body fluids containing the bacteria. The bacteria may enter the body through mucous membranes, skin injuries, or by ingestion. The mechanism of pathogenicity is not well understood.

Leptospirosis is extremely rare in the United States, although it is endemic in Hawaii; 50% of all cases in the United States come from Hawaii.[2] It is more common in tropical than in temperate climates, and individuals who work with animals or animal products are most at risk. The bacteria can also be cultivated in specialized media, with growth observed in broth in a few days to four weeks; however, diagnosis of leptospirosis is generally made using faster methods, such as detection of antibodies to Leptospira spp. in patient samples using serologic testing. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), slide agglutination, and indirect immunofluorescence tests may all be used for diagnosis. Treatment for leptospirosis involves broad-spectrum antibiotics such as penicillin and doxycycline. For more serious cases of leptospirosis, antibiotics may be given intravenously.

- What is the most common cause of a kidney infection?

- What are the most common symptoms of a kidney infection?

Nongonococcal Urethritis (NGU)

There are two main categories of bacterial urethritis: gonorrhoeal and nongonococcal. Gonorrheal urethritis is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae and is associated with gonorrhoea, a common STI. This cause of urethritis will be discussed in Bacterial Infections of the Reproductive System. The term nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) refers to inflammation of the urethra that is unrelated to N. gonorrhoeae. In women, NGU is often asymptomatic. In men, NGU is typically a mild disease, but can lead to purulent discharge and dysuria. Because the symptoms are often mild or nonexistent, most infected individuals do not know that they are infected, yet they are carriers of the disease. Asymptomatic patients also have no reason to seek treatment, and although not common, untreated NGU can spread to the reproductive organs, causing pelvic inflammatory disease and salpingitis in women and epididymitis and prostatitis in men. Important bacterial pathogens that cause nongonococcal urethritis include Chlamydia trachomatis, Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Mycoplasma hominis.

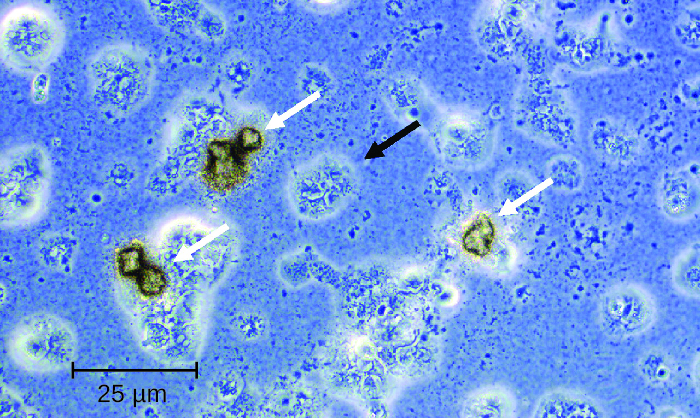

C. trachomatis is a difficult-to-stain, gram-negative bacterium with an ovoid shape. An intracellular pathogen, C. trachomatis causes the most frequently reported STI in the United States, chlamydia. Although most persons infected with C. trachomatis are asymptomatic, some patients can present with NGU. C. trachomatis can also cause non-urogenital infections such as the ocular disease trachoma (see Bacterial Infections of the Skin and Eyes). The life cycle of C. trachomatis is illustrated in Figure 24.7.

C. trachomatis has multiple possible virulence factors that are currently being studied to evaluate their roles in causing disease. These include polymorphic outer-membrane autotransporter proteins, stress response proteins, and type III secretion effectors. The type III secretion effectors have been identified in gram-negative pathogens, including C. trachomatis. This virulence factor is an assembly of more than 20 proteins that form what is called an injectisome for the transfer of other effector proteins that target the infected host cells. The outer-membrane autotransporter proteins are also an effective mechanism of delivering virulence factors involved in colonization, disease progression, and immune system evasion.

Other species associated with NGU include Mycoplasma genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and Mycoplasma hominis. These bacteria are commonly found in the normal microbiota of healthy individuals, who may acquire them during birth or through sexual contact, but they can sometimes cause infections leading to urethritis (in males and females) or vaginitis and cervicitis (in females).

M. genitalium is a more common cause of urethritis in most settings than N. gonorrhoeae, although it is less common than C. trachomatis. It is responsible for approximately 30% of recurrent or persistent infections, 20–25% of nonchlamydial NGU cases, and 15%–20% of NGU cases. M. genitalium attaches to epithelial cells and has substantial antigenic variation that helps it evade host immune responses. It has lipid-associated membrane proteins that are involved in causing inflammation.

Several possible virulence factors have been implicated in the pathogenesis of U. urealyticum (Figure 24.7). These include the ureaplasma proteins phospholipase A, phospholipase C, multiple banded antigen (MBA), urease, and immunoglobulin α protease. The phospholipases are virulence factors that damage the cytoplasmic membrane of target cells. The immunoglobulin α protease is an important defence against antibodies. It can generate hydrogen peroxide, which may adversely affect host cell membranes through the production of reactive oxygen species.

Treatments differ for gonorrhoeal and nongonococcal urethritis. However, N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis are often simultaneously present, which is an important consideration for treatment. NGU is most commonly treated using tetracyclines (such as doxycycline) and azithromycin; erythromycin is an alternative option. Tetracyclines and fluoroquinolones are most commonly used to treat U. urealyticum, but resistance to tetracyclines is becoming an increasing problem.[3] While tetracyclines have been the treatment of choice for M. hominis, increasing resistance means that other options must be used. Clindamycin and fluoroquinolones are alternatives. M. genitalium is generally susceptible to doxycycline, azithromycin, and moxifloxacin. Like other mycoplasma, M. genitalium does not have a cell wall and therefore β-lactams (including penicillins and cephalosporins) are not effective treatments.

- What are the three most common causes of urethritis?

- What three members of the normal microbiota can cause urethritis?

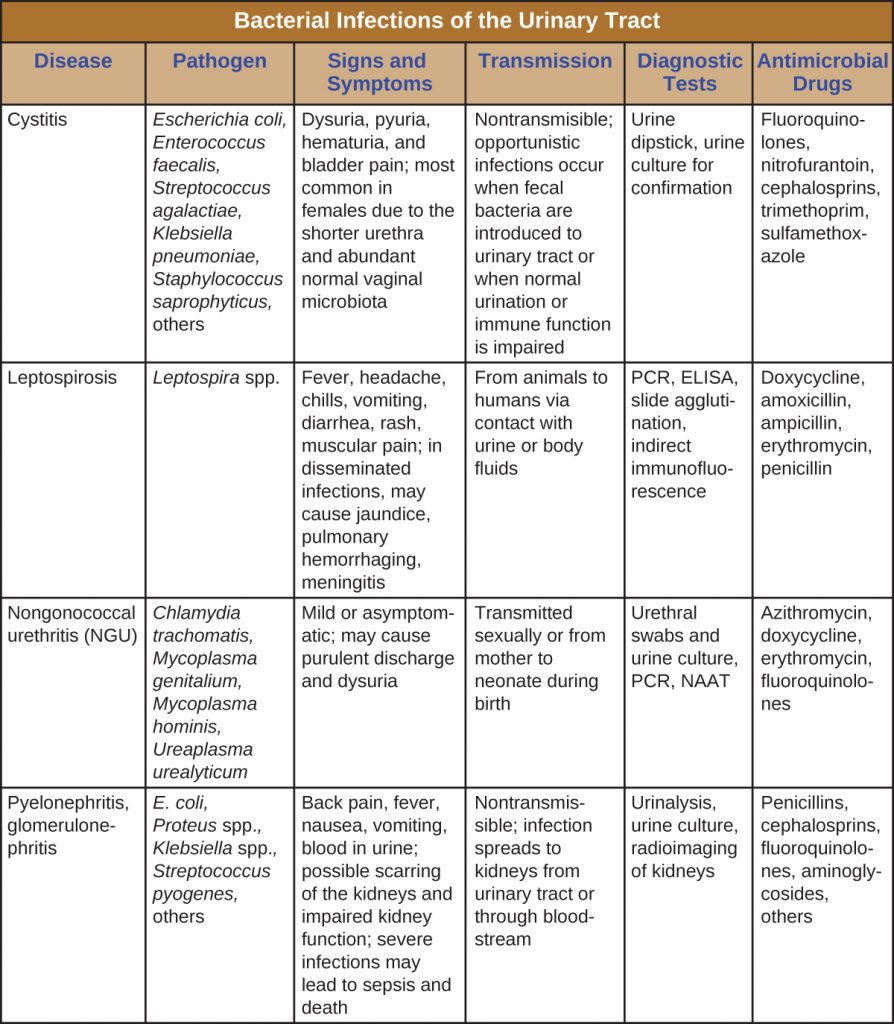

DISEASE PROFILE: Bacterial Infections of the Urinary Tract

Urinary tract infections can cause inflammation of the urethra (urethritis), bladder (cystitis), and kidneys (pyelonephritis), and can sometimes spread to other body systems through the bloodstream. Table 24.1 captures the most important features of various types of UTIs.

Table 24.1. Bacterial Infections of the Urinary Tract

Key Takeaways

- Bacterial cystitis is commonly caused by faecal bacteria such as E. coli.

- Pyelonephritis is a serious kidney infection that is often caused by bacteria that travel from infections elsewhere in the urinary tract and may cause systemic complications.

- Leptospirosis is a bacterial infection of the kidney that can be transmitted by exposure to infected animal urine, especially in contaminated water. It is more common in tropical than in temperate climates.

- Nongonococcal urethritis (NGU) is commonly caused by C. trachomatis, M. genitalium, Ureaplasma urealyticum, and M. hominis.

- Diagnosis and treatment for bacterial urinary tract infections varies. Urinalysis (e.g., for leukocyte esterase levels, nitrite levels, microscopic evaluation, and culture of urine) is an important component in most cases. Broad-spectrum antibiotics are typically used.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- What is pyuria?

Critical Thinking

- What are some factors that would increase an individual’s risk of contracting leptospirosis?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_23_02_Dipstick

- OSC_Microbio_23_02_Leptospira

- OSC_Microbio_23_02_Microassay

- Tibor Fulop. “Acute Pyelonephritis” Medscape, 2015. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/245559-overview. ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. “Leptospirosis.” 2015. http://www.cdc.gov/leptospirosis/health_care_workers. ↵

- Ken B Waites. “Ureaplasma Infection Medication.” Medscape, 2015. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/231470-medication. ↵