23. Respiratory System Infections

23.1 Anatomy and Normal Microbiota of the Respiratory Tract

Learning Objectives

- Describe the major anatomical features of the upper and lower respiratory tract

- Describe the normal microbiota of the upper and lower respiratory tracts

- Explain how microorganisms overcome defences of upper and lower respiratory-tract membranes to cause infection

- Explain how microbes and the respiratory system interact and modify each other in healthy individuals and during an infection

CLINICAL FOCUS: Part 1

John, a 65-year-old man with asthma and type 2 diabetes, works as a sales associate at a local home improvement store. Recently, he began to feel quite ill and made an appointment with his family physician. At the clinic, John reported experiencing headache, chest pain, coughing, and shortness of breath. Over the past day, he had also experienced some nausea and diarrhoea. A nurse took his temperature and found that he was running a fever of 40 °C (104 °F).

John suggested that he must have a case of influenza (flu), and regretted that he had put off getting his flu vaccine this year. After listening to John’s breathing through a stethoscope, the physician ordered a chest radiography and collected blood, urine, and sputum samples.

- Based on this information, what factors may have contributed to John’s illness?

Jump to the next Clinical Focus box.

The primary function of the respiratory tract is to exchange gases (oxygen and carbon dioxide) for metabolism. However, inhalation and exhalation (particularly when forceful) can also serve as a vehicle of transmission for pathogens between individuals.

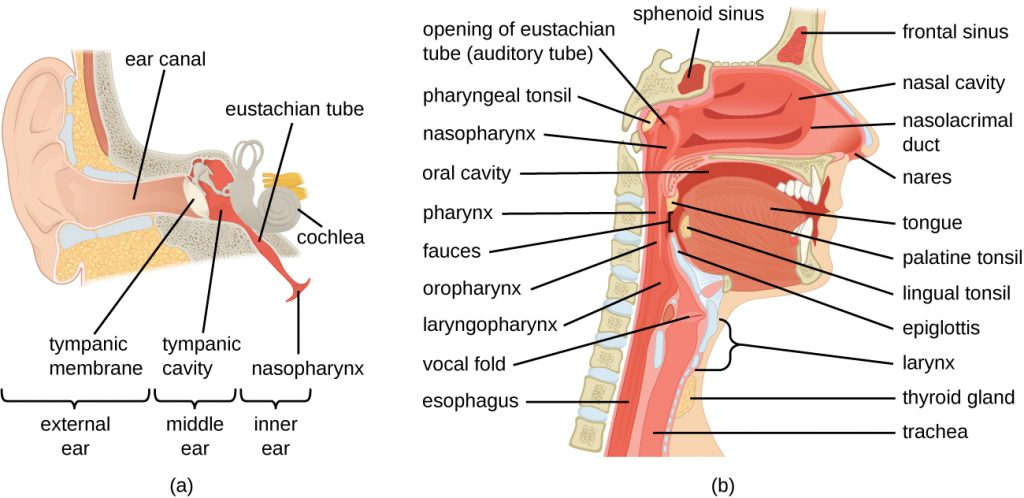

Anatomy of the Upper Respiratory system

The respiratory system can be conceptually divided into upper and lower regions at the point of the epiglottis, the structure that seals off the lower respiratory system from the pharynx during swallowing (Figure 23.2). The upper respiratory system is in direct contact with the external environment. The nares (or nostrils) are the external openings of the nose that lead back into the nasal cavity, a large air-filled space behind the nares. These anatomical sites constitute the primary opening and first section of the respiratory tract, respectively. The nasal cavity is lined with hairs that trap large particles, like dust and pollen, and prevent their access to deeper tissues. The nasal cavity is also lined with a mucous membrane and Bowman’s glands that produce mucus to help trap particles and microorganisms for removal. The nasal cavity is connected to several other air-filled spaces. The sinuses, a set of four, paired small cavities in the skull, communicate with the nasal cavity through a series of small openings. The nasopharynx is part of the upper throat extending from the posterior nasal cavity. The nasopharynx carries air inhaled through the nose. The middle ear is connected to the nasopharynx through the eustachian tube. The middle ear is separated from the outer ear by the tympanic membrane, or ear drum. And finally, the lacrimal glands drain to the nasal cavity through the nasolacrimal ducts (tear ducts). The open connections between these sites allow microorganisms to move from the nasal cavity to the sinuses, middle ears (and back), and down into the lower respiratory tract from the nasopharynx.

The oral cavity is a secondary opening for the respiratory tract. The oral and nasal cavities connect through the fauces to the pharynx, or throat. The pharynx can be divided into three regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx. Air inhaled through the mouth does not pass through the nasopharynx; it proceeds first through the oropharynx and then through the laryngopharynx. The palatine tonsils, which consist of lymphoid tissue, are located within the oropharynx. The laryngopharynx, the last portion of the pharynx, connects to the larynx, which contains the vocal fold (Figure 23.2).

- Identify the sequence of anatomical structures through which microbes would pass on their way from the nares to the larynx.

- What two anatomical points do the eustachian tubes connect?

Anatomy of the Lower Respiratory System

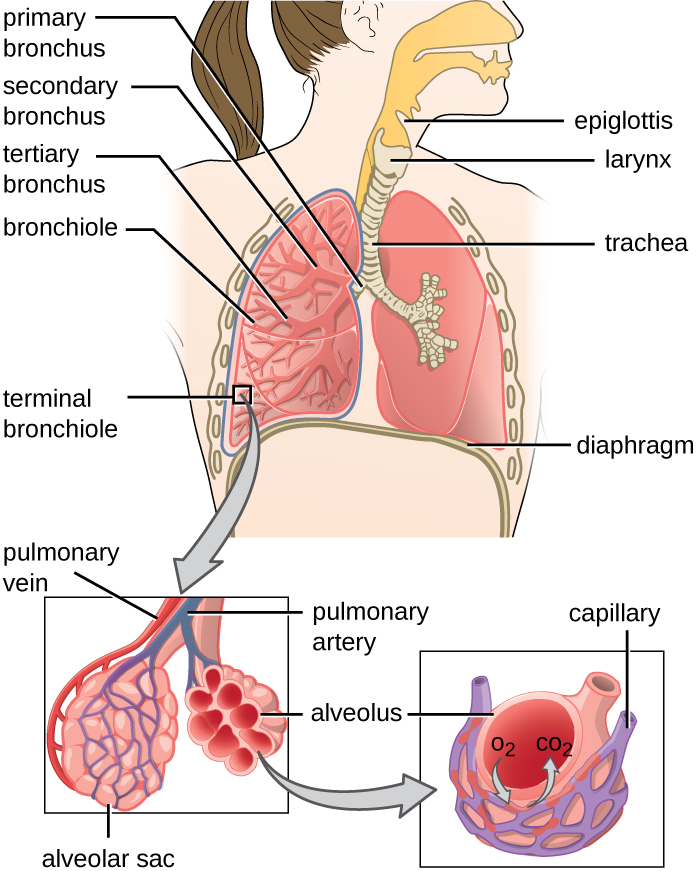

The lower respiratory system begins below the epiglottis in the larynx or voice box (Figure 23.3). The trachea, or windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube extending from the larynx that provides an unobstructed path for air to reach the lungs. The trachea bifurcates into the left and right bronchi as it reaches the lungs. These paths branch repeatedly to form smaller and more extensive networks of tubes, the bronchioles. The terminal bronchioles formed in this tree-like network end in cul-de-sacs called the alveoli. These structures are surrounded by capillary networks and are the site of gas exchange in the respiratory system. Human lungs contain on the order of 400,000,000 alveoli. The outer surface of the lungs is protected with a double-layered pleural membrane. This structure protects the lungs and provides lubrication to permit the lungs to move easily during respiration.

Defences of the Respiratory System

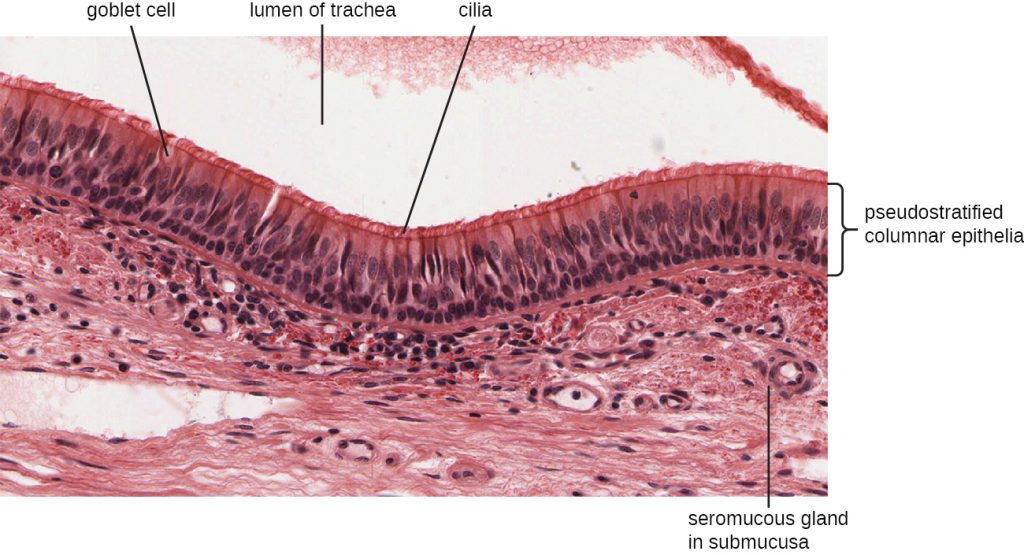

The inner lining of the respiratory system consists of mucous membranes (Figure 23.4) and is protected by multiple immune defences. The goblet cells within the respiratory epithelium secrete a layer of sticky mucus. The viscosity and acidity of this secretion inhibits microbial attachment to the underlying cells. In addition, the respiratory tract contains ciliated epithelial cells. The beating cilia dislodge and propel the mucus, and any trapped microbes, upward to the epiglottis, where they will be swallowed. Elimination of microbes in this manner is referred to as the mucociliary escalator effect and is an important mechanism that prevents inhaled microorganisms from migrating further into the lower respiratory tract.

The upper respiratory system is under constant surveillance by mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), including the adenoids and tonsils. Other mucosal defences include secreted antibodies (IgA), lysozyme, surfactant, and antimicrobial peptides called defensins. Meanwhile, the lower respiratory tract is protected by alveolar macrophages. These phagocytes efficiently kill any microbes that manage to evade the other defences. The combined action of these factors renders the lower respiratory tract nearly devoid of colonized microbes.

- Identify the sequence of anatomical structures through which microbes would pass on their way from the larynx to the alveoli.

- Name some defences of the respiratory system that protect against microbial infection.

Normal Microbiota of the Respiratory System

The upper respiratory tract contains an abundant and diverse microbiota. The nasal passages and sinuses are primarily colonized by members of the Firmicutes, Actinobacteria, and Proteobacteria. The most common bacteria identified include Staphylococcus epidermidis, viridans group streptococci (VGS), Corynebacterium spp. (diphtheroids), Propionibacterium spp., and Haemophilus spp. The oropharynx includes many of the same isolates as the nose and sinuses, with the addition of variable numbers of bacteria like species of Prevotella, Fusobacterium, Moraxella, and Eikenella, as well as some Candida fungal isolates. In addition, many healthy humans asymptomatically carry potential pathogens in the upper respiratory tract. As much as 20% of the population carry Staphylococcus aureus in their nostrils.[1] The pharynx, too, can be colonized with pathogenic strains of Streptococcus, Haemophilus, and Neisseria.

The lower respiratory tract, by contrast, is scantily populated with microbes. Of the organisms identified in the lower respiratory tract, species of Pseudomonas, Streptococcus, Prevotella, Fusobacterium, and Veillonella are the most common. It is not clear at this time if these small populations of bacteria constitute a normal microbiota or if they are transients.

Many members of the respiratory system’s normal microbiota are opportunistic pathogens. To proliferate and cause host damage, they first must overcome the immune defences of respiratory tissues. Many mucosal pathogens produce virulence factors such as adhesins that mediate attachment to host epithelial cells, or polysaccharide capsules that allow microbes to evade phagocytosis. The endotoxins of gram-negative bacteria can stimulate a strong inflammatory response that damages respiratory cells. Other pathogens produce exotoxins, and still others have the ability to survive within the host cells. Once an infection of the respiratory tract is established, it tends to impair the mucociliary escalator, limiting the body’s ability to expel the invading microbes, thus making it easier for pathogens to multiply and spread.

Vaccines have been developed for many of the most serious bacterial and viral pathogens. Several of the most important respiratory pathogens and their vaccines, if available, are summarized in Table 23.1. Components of these vaccines will be explained later in the chapter.

Table 23.1. Some Important Respiratory Diseases and Vaccines[2]

| Some Important Respiratory Diseases and Vaccines | ||

|---|---|---|

| Disease | Pathogen | Available Vaccine(s) |

| Chickenpox/shingles | Varicella-zoster virus | Varicella (chickenpox) vaccine, herpes zoster (shingles) vaccine |

| Common cold | Rhinovirus | None |

| Diphtheria | Corynebacterium diphtheriae | DtaP, Tdap, DT,Td, DTP |

| Epiglottitis, otitis media | Haemophilus influenzae | Hib |

| Influenza | Influenza viruses | Inactivated, FluMist |

| Measles | Measles virus | MMR |

| Pertussis | Bordetella pertussis | DTaP, Tdap |

| Pneumonia | Streptococcus pneumoniae | Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV13), pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23) |

| Rubella (German measles) | Rubella virus | MMR |

| Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) | SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV) | None |

| Tuberculosis | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | BCG |

- What are some pathogenic bacteria that are part of the normal microbiota of the respiratory tract?

- What virulence factors are used by pathogens to overcome the immune protection of the respiratory tract?

Signs and Symptoms of Respiratory Infection

Microbial diseases of the respiratory system typically result in an acute inflammatory response. These infections can be grouped by the location affected and have names ending in “itis”, which literally means inflammation of. For instance, rhinitis is an inflammation of the nasal cavities, often characteristic of the common cold. Rhinitis may also be associated with hay fever allergies or other irritants. Inflammation of the sinuses is called sinusitis inflammation of the ear is called otitis. Otitis media is an inflammation of the middle ear. A variety of microbes can cause pharyngitis, commonly known as a sore throat. An inflammation of the larynx is called laryngitis. The resulting inflammation may interfere with vocal cord function, causing voice loss. When tonsils are inflamed, it is called tonsillitis. Chronic cases of tonsillitis may be treated surgically with tonsillectomy. More rarely, the epiglottis can be infected, a condition called epiglottitis. In the lower respiratory system, the inflammation of the bronchial tubes results in bronchitis. Most serious of all is pneumonia, in which the alveoli in the lungs are infected and become inflamed. Pus and oedema accumulate and fill the alveoli with fluids (called consolidations). This reduces the lungs’ ability to exchange gases and often results in a productive cough expelling phlegm and mucus. Cases of pneumonia can range from mild to life-threatening, and remain an important cause of mortality in the very young and very old.

- Describe the typical symptoms of rhinitis, sinusitis, pharyngitis, and laryngitis.

CASE IN POINT: Smoking-Associated Pneumonia

Camila is a 22-year-old student who has been a chronic smoker for 5 years. Recently, she developed a persistent cough that has not responded to over-the-counter treatments. Her doctor ordered a chest radiograph to investigate. The radiological results were consistent with pneumonia. In addition, Streptococcus pneumoniae was isolated from Camila’s sputum.

Smokers are at a greater risk of developing pneumonia than the general population. Several components of tobacco smoke have been demonstrated to impair the lungs’ immune defences. These effects include disrupting the function of the ciliated epithelial cells, inhibiting phagocytosis, and blocking the action of antimicrobial peptides. Together, these lead to a dysfunction of the mucociliary escalator effect. The organisms trapped in the mucus are therefore able to colonize the lungs and cause infections rather than being expelled or swallowed.

Key Takeaways

- The respiratory tract is divided into upper and lower regions at the epiglottis.

- Air enters the upper respiratory tract through the nasal cavity and mouth, which both lead to the pharynx. The lower respiratory tract extends from the larynx into the trachea before branching into the bronchi, which divide further to form the bronchioles, which terminate in alveoli, where gas exchange occurs.

- The upper respiratory tract is colonized by an extensive and diverse normal microbiota, many of which are potential pathogens. Few microbial inhabitants have been found in the lower respiratory tract, and these may be transients.

- Members of the normal microbiota may cause opportunistic infections, using a variety of strategies to overcome the innate nonspecific defences (including the mucociliary escalator) and adaptive specific defences of the respiratory system.

- Effective vaccines are available for many common respiratory pathogens, both bacterial and viral.

- Most respiratory infections result in inflammation of the infected tissues; these conditions are given names ending in -itis, such as rhinitis, sinusitis, otitis, pharyngitis, and bronchitis.

Multiple Choice

Fill in the Blank

Short Answer

- Explain why the lower respiratory tract is essentially sterile.

- Explain why pneumonia is often a life-threatening disease.

Critical Thinking

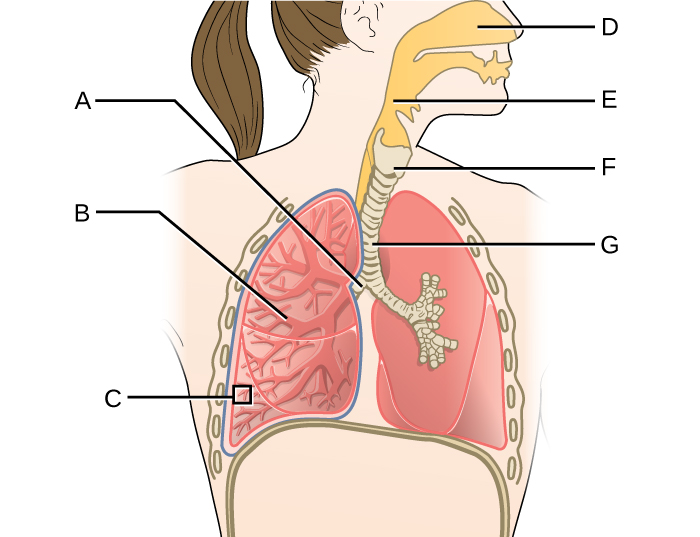

- Name each of the respiratory tract structures in the above diagram, and state whether each has a relatively large or small normal microbiota.

- Cystic fibrosis causes, among other things, excess mucus to be formed in the lungs. The mucus is very dry and caked, unlike the moist, more-fluid mucus of normal lungs. What effect do you think that has on the lung’s defences?

- Why do you think smokers are more likely to suffer from respiratory tract infections?

Media Attributions

- OSC_Microbio_22_01_UpperResp

- OSC_Microbio_22_01_LowerResp

- Web

- OSC_Microbio_22_01_ArtConnect_img

- J. Kluytmans et al. “Nasal Carriage of Staphylococcus aureus: Epidemiology, Underlying Mechanisms, and Associated Risks.” Clinical Microbiology Reviews 10 no. 3 (1997):505–520. ↵

- Full names of vaccines listed in table: Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib); Diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DtaP); tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap); diphtheria and tetanus (DT); tetanus and diphtheria (Td); diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (DTP); Bacillus Calmette-Guérin; Measles, mumps, rubella (MMR) ↵