9.3. Intellectual Property and Copyright

The rise of information systems has resulted in rethinking how to deal with intellectual property. From the increase in patent applications swamping the government’s patent office to the new laws that must be put in place to enforce copyright protection, digital technologies have impacted our behavior.

Digital technologies have driven a rise in new intellectual property claims and made it much more difficult to defend intellectual property. Intellectual property is defined as “property (as an idea, invention, or process) that derives from the work of the mind or intellect” (Merriam-Webster Dictionary, n.d.). This could include creations such as song lyrics, a computer program, a new type of toaster, or even a sculpture. Practically speaking, it is difficult to protect an idea. Instead, intellectual property laws are written to protect the tangible results of an idea. In other words, just coming up with a song in your head is not protected, but if you write it down, it can be protected.

Protection of intellectual property is important because it gives people an incentive to be creative. Innovators with great ideas will be more likely to pursue those ideas if they have a clear understanding of how they will benefit. The Canadian Intellectual Property Office (CIPO) is a special operating agency of Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada. They deliver intellectual property (IP) services in Canada and educate Canadians on how to use IP more effectively. The CIPO grants patents, and registers trademarks and provides copyright protection for original works. You can learn more by taking their training modules on the CIPO website. Outside of the US and Canada, intellectual property protections vary. You can find out more about a specific country’s intellectual property laws by visiting the World Intellectual Property Organization.

While protecting intellectual property is important because of the incentives it provides, it is also necessary to limit the amount of benefit that can be received and allow the results of ideas to become part of the public domain. The following sections address three of the best-known intellectual property protections: copyright, patent, and trademark.

Copyright

Copyright is the protection given to songs, computer programs, books, and other creative works. Any work that has an “author” can be copyrighted. Under the terms of copyright, the author of a work controls what can be done with the work, including:

- Who can make copies of the work.

- Who can make derivative works from the original work.

- Who can perform the work publicly.

- Who can display the work publicly.

- Who can distribute the work.

Many times a work is not owned by an individual but is instead owned by a publisher with whom the original author has an agreement. In return for the rights to the work, the publisher will market and distribute the work and then pay the original author a portion of the proceeds. Currently, copyright protection lasts for the entirety of the author’s life plus 50 years after his or her death. In the case of a work that has multiple authors, the copyright will last for 50 years after the death of the last surviving author. However, the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement will require Canada to extend the terms of copyright protection offered in the Copyright Act. There are a few exceptions to this as outlined by the Canadian Intellectual Property Office.

Fair use vs. Fair Dealing

Fair use is described in Section 107 of the United States Copyright Act, which states that the “fair use of a copyrighted work … for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” Similarly fair dealing which is outlined in Section 29 of the Canadian Copyright Act (the ‘Act’) permits the use of a copyright-protected work without permission or payment as long as the use falls within one of the listed purposes in the Act, and the dealing is fair. The most important difference between fair use and fair dealing is that the list of purposes available for fair use are illustrative, while the purposes for fair dealing are exhaustive, meaning that, in theory, fair use is more flexible and is applicable to a wider variety of situations than fair dealing. To learn more about fair dealing and the six criteria: purpose, character, amount, alternatives, nature, and effect of the dealing check out the University of Alberta’s page on Fair Dealing.

Unfortunately, the specific guidelines for what is considered fair use/fair dealing and what constitutes copyright violation are not well defined. Fair use/fair dealing is a well-known and respected concept and will only be challenged when copyright holders feel that the integrity or market value of their work is being threatened. Canadian copyright laws and regulations are designed to ensure that the rights of creators and other rights-holders are recognized and protected, and to promote access to copyrighted works. Canada’s domestic copyright framework must also meet our international obligations and be consistent with international standards endorsed by Canada. Effective copyright protection is key to cultural expression, citizen engagement, and economic growth powered by the rapid expansion of the knowledge-based economy.

Copyright and Digital Technologies

As digital technologies have changed so has what it means to create, copy, and distribute media. In Canada, the Notice and Notice Regime is a tool established in the Copyright Act to help copyright owners deal with online copyright infringement (e.g. illegal downloading) to protect their copyright material while respecting the interests and freedom of users. Ultimately, it formalized a voluntary industry-based practice that had been in place for several years.

Therefore, when a copyright owner thinks that an Internet user might be infringing their copyright, they can send a notice of alleged infringement to the user’s ISP. Notice and Notice regime requires that the ISP forward (e.g. via email) the notice of alleged infringement to the user and then inform the copyright owner once this has been done.

For example, a copyright owner identifies an internet user with a Canadian internet protocol (IP) address downloading a movie from a pirate site. Not knowing who the person is, the copyright owner can send a notice of alleged infringement to the ISP that owns the relevant IP address. The ISP must then forward the notice to its subscriber who was using that IP address at the time of the alleged infringement.

Creative Commons

In chapter 4 we explored the topic of open-source software. Open-source software has few or no copyright restrictions. The creators of the software publish their code and make their software available for others to use and distribute for free. This is great for software, but what about other forms of copyrighted works? If an artist or writer wants to make their works available, how can they go about doing so while still protecting the integrity of their work? Creative Commons is the solution to this problem.

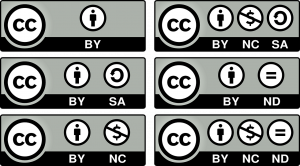

Creative Commons is a nonprofit organization that provides legal tools for artists and authors. The tools offered make it simple to license artistic or literary work for others to use or distribute in a manner consistent with the author’s intentions. Creative Commons licenses are indicated with the symbol. It is important to note that Creative Commons and public domain are not the same. When something is in the public domain, it has absolutely no restrictions on its use or distribution. Works whose copyrights have expired are in the public domain. By using a Creative Commons license, authors can control the use of their work while still making it widely accessible. By attaching a Creative Commons license to their work, a legally binding license is created. For a full listing of the licenses and to learn much more about Creative Commons, visit their website.

“Chapter 12: The Ethical and Legal Implications of Information Systems” from Information Systems for Business and Beyond (2019) by David Bourgeois is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.