9.3 Measurement at Recognition

PPE assets are initially measured at their cost, which is the cash or fair value of other assets given to acquire the asset. A few key inclusions and exclusions need to be considered in this definition.

Any cost required to purchase the asset and bring it to its location of operation should be capitalized. As well, any further costs required to prepare the asset for its intended use should also be capitalized. The following is a list of some of the costs that should be included in the capitalized amount:

- Purchase price, including all non-recoverable tax and duties, net of discounts

- Delivery and handling

- Direct employee labour costs to construct or acquire the asset

- Site preparation

- Other installation costs

- Net material and labour costs required to test the asset for proper functionality

- Professional fees directly attributable to the purchase

- Estimates of decommissioning and site restoration costs

Costs that should not be included in the initial capitalized amount include:

- Initial operating losses

- Training costs for employees

- Costs of opening a new facility

- Costs of introducing a new product or service

- Costs of reorganization and operation at a new location

- Administration and general overhead costs

- Other revenue or expenses that are incidental to the development of the PPE

Let’s consider some specific assets.

Land

Land typically includes the purchase price; closing costs (title fees, legal fees, recording fees); costs incurred to make the land ready for its intended use (grading, filling, draining and clearing); the cost of assuming any liens (taxes in arrears, mortgages or encumbrances on the property); any additional land improvements (such as landscaping) with an indefinite life.

If land is purchased to construct a building, all the costs incurred up to the excavation for the new building are considered land costs. Removal of any old buildings and clearing the remains are considered land costs because these costs are necessary to get the land in condition and ready for its intended purpose. Items with unlimited life such as roads, street lights, sewers and drainage are often changed to land because they are relatively permanent and maintained. Improvements with limited lives such as private driveways, sidewalks, fencing and parking lots are usually kept separate and recorded as land improvements so they can be depreciated over their useful lives.

If any proceeds are received from getting the land ready for its intended use would be treated as a reduction in the land cost. An example: an amounts received for salvaged material from the demolition of an old building or the sale of timber that has been cleared.

Buildings

If land is purchases with a building that is onsite and that building is torn down to make way for a new building, the cost of getting the land ready for use (tearing the building down) is part of land. However, if a company already has a building and wants to tear the old building to construct a new building, the cost of the demolition is expensed as disposal costs of the old building – that could increase the loss on disposal of the old building.

Leasehold Improvements

As the account name implies, leasehold improvements are costs incurred to get a leased property ready to use. If a company has a long-term lease, usually any leasehold improvements made to the property will revert to the lessor (owner) at the end of the lease. Leasehold improvements is amortized over the remaining life of the lease, or the useful life of the improvements, whichever is shorter.

Equipment

The term equipment can cover a wide range of assets. Equipment can include office equipment, factory equipment, machinery, furnishings, and at times various types of motorized vehicles. The cost of these assets include the invoiced purchase price as well as any other costs incurred to make the asset ready to use. Those costs could include: freight and delivery, insurance while in transit, assembly and installation costs, testing and costs of make any adjustments to the asset to make it operate as intended.

9.3.1 Self-Constructed Assets

When a company chooses to build its own PPE, further accounting problems may arise. Without a transaction with an external party, the cost of the asset may not be clear. Although the direct materials and labour needed to construct the asset are usually easy to identify, the costs of overheads and other indirect elements may be more difficult to apply. The general rule to apply here is that only costs directly attributable to the construction of the asset should be capitalized. This means that any allocation of general overheads or other indirect costs is not appropriate. As well, any internal profits or abnormal costs, such as material wastage, are excluded from the capitalized amount.

Determining the total cost of a self-constructed asset can be complicated. Without a firm purchase or contract price, the company has to review a number of expenditures that were incurred to arrive at a total cost. Operations and accounting have to work closely together to ensure that all costs related to the construction of an asset are capitalized rather than expensed. Careful review of invoices is required.

Labour costs can be capitalized if the costs are directly related to the construction of long-term assets. Normally, these costs are easy to track since they can be traced directly to actual work orders. Material costs can also be easily traced since those costs are again easy to trace in the construction of an asset. Indirect costs (overhead) are slightly harder to determine but with careful documentation even these costs can be traced and accounted for.

9.3.2. Borrowing Costs

One particular problem that arises when a company constructs its own PPE is how to treat any interest incurred during the construction phase. IAS 23 (IAS, 2007) requires that any interest that is directly attributable to the construction of a qualifying asset be capitalized. A qualifying asset is any asset that takes a substantial amount of time to be prepared for its intended use. This definition could thus include inventories as well as PPE, although the standard does not require capitalization of interest for inventory items that are produced in large quantities on a regular basis.

If a PPE asset is qualified under this definition, then a further question arises as to how much interest should be capitalized. The general rule is that any interest that could have been avoided by not constructing the asset should be capitalized. If the company has obtained specific financing for the project, then the direct interest costs should be easy to identify. However, note that any interest revenue earned on excess funds that are invested during the construction process should be deducted from the total amount capitalized.

If the project is financed from general borrowings and not a specific loan, identification of the capitalized interest is more complicated. The general approach here is to apply a weighted average cost of borrowing to the total project cost and capitalize this amount. Some judgment will be required to determine this weighted average cost in large, complex organizations.

Interest capitalization should commence when the company first incurs expenditures for the asset, first incurs borrowing costs, and first undertakes activities necessary to prepare the asset for its intended use. Interest capitalization should cease once substantially all of the activities necessary to get the asset ready for its intended use are complete. Interest capitalization should also be stopped if active development of the project is suspended for an extended period of time.

Many aspects of the accounting standards for interest capitalization require professional judgment, and accountants will need to be careful in applying this standard.

9.3.3 Asset Retirement Obligations

For certain types of PPE assets, the company may have an obligation to dismantle, clean up, or restore the site of the asset once its useful life has been consumed. An example would be a drilling site for an oil exploration company. Once the well has finished extracting the oil from the reserve, local authorities may require the company to remove the asset and restore the site to a natural state. Even if there is no legal requirement to do so, the company may still have created an expectation that it will do so through its own policies and previous conduct. This type of non-legally binding commitment is referred to as a constructive obligation. Where these types of legal and constructive obligations exist, the company is required to report a liability on the balance sheet equal to the present value of these future costs, with the offsetting debit being record as part of the capital cost of the asset. This topic will be covered in more detail in Chapter 10, but for now, just be aware that this type of cost will be capitalized as part of the PPE asset cost.

Consider the following asset retirement obligation (ARO) example:

Basic Drilling Company follows IFRS. On January 1, Y4, the company purchased an oil drilling platform for $6,000,000. It’s estimated that this platform will last 6 years. At the end of the platform’s useful life, the company expects cleanup, remediation and dismantling costs related to the platform to be $1,000,000. The company uses a discount rate of 5%.

Prepare the journal entries for Year 4 and Year 5 related to this transaction.

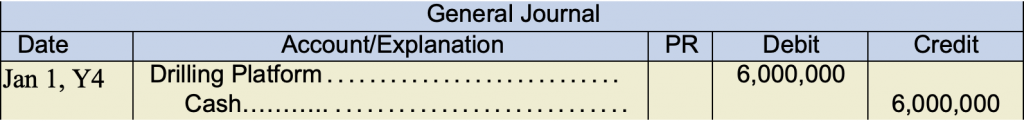

On January 1, Y4, there are two separate entries that should be made. The entries can be combined but for tracking and audit purposes, it’s better to have each transaction separate:

Record the purchase of the drilling platform

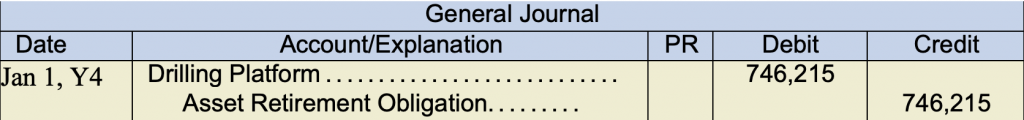

Since we know that the future value of the remediation is estimated to be $1,000,000, we have to determine the present value to set up the liability (using FV = 1,000,000, PMT = 0, Rate = 5% and Term = 6 years). The result is $746,215 (rounded).

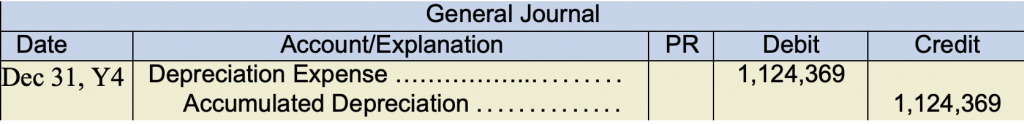

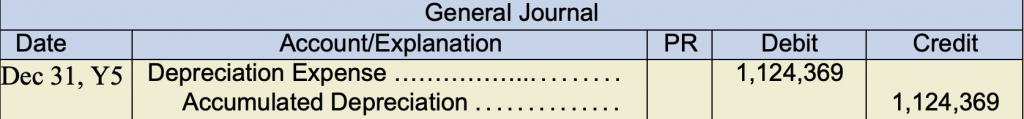

Since we know that the future value of the remediation is estimated to be $1,000,000, we have to determine the present value to set up the liability (using FV = 1,000,000, PMT = 0, Rate = 5% and Term = 6 years). The result is $746,215 (rounded)At the end of the year, two entries are required. The first entry is depreciation based on the total cost of the drilling platform (6,000,000 + 746,215) = $6,746,215 divided by the useful life of 6 years.

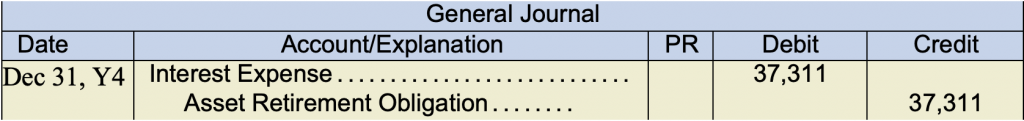

The second entry is to record interest expense. We use the effective interest method for IFRS. (746,215 × 5%) The difference here between IFRS and ASPE would be the account to debit. IFRS use Interest Expense. With ASPE use Accretion Expense:

In Year 5, the depreciation entry remains the same:

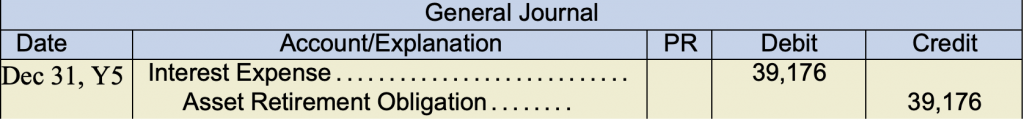

Since we know that the future value of the remediation is estimated to be $1,000,000, we have to determine the present value to set up the liability (using FV = 1,000,000, PMT = 0, Rate = 5% and Term = 6 years). The result is $746,215 (rounded)At the end of the year, two entries are required. The first entry is depreciation based on the total cost of the drilling platform (6,000,000 + 746,215) = $6,746,215 divided by the useful life of 6 years.In Year 5, the interest expense amount will change since we are using the effective interest method. Remember, we are trying to get our ARO amount to be the estimated liability of $1,000,000. The amount of interest in Year 5 would be:

($746,215 + $37,311) × 5% = $39,176

Be aware that other factors could influence and change the ARO and the asset amount. First, the liability at the end of the assets useful life is an estimate. For IFRS, the estimated remediation amount should be revisited annually and updated as needed. If an update is required, the asset value will change, causing a change to depreciation. Also, this example ignored inflation. If inflation exists, the amount will impact the liability and the asset calculation as well.

9.3.4. Lump Sum Purchases

There are instances where a business may purchase a group of PPE assets for a single price. This is referred to as a lump sum, or basket, purchase. When this occurs, the accounting issue is how to allocate the purchase price to the individual components purchased. The normal practice is to allocate the purchase price based on the relative fair value of each component. Of course, this requires that information about the assets’ fair values be available and reliable. Often, insurance appraisals, property tax assessments, depreciated replacement costs, and other appraisals can be used. The reliability and suitability of the source used will be a matter of judgment on the part of the accountant.

Consider the following example. A company purchases land and building together for a total price of $850,000. The most recent property tax assessment from the local government indicated that the building’s assessed value was $600,000 and the land’s assessed value was $150,000. The total purchase price of the components would be allocated as follows:

| Land | (150,000 × 850,000) ÷ (150,000 + 600,000) | = $170,000 |

|---|---|---|

| Building | (600,000 × 850,000) ÷ (150,000 + 600,000) | = $680,000 |

| Total | = $850,000 |

9.3.5. Non-monetary Exchanges

When PPE assets are acquired through payments other than cash, the question that arises is how to value the transaction. Two particular types of transactions can occur: 1) a company can acquire a PPE asset by issuing its own shares, or 2) a company can acquire a PPE asset by exchanging it with another asset the company currently owns.

Asset Acquired by Issuing Shares

When a company issues its own shares to acquire an asset, the transaction should be recorded at the fair value of the asset acquired. IFRS presumes that this fair value should normally be obtainable. This makes sense, as it unlikely that a company would acquire an asset without having a reasonable estimate of its value. If the fair value of the asset acquired is not determinable, then the asset should be reported at the fair value of the shares given up. This value is relatively easy to determine for an actively traded public company. In cases where neither the value of the asset nor the value of the shares can be reliably determined, the asset could not be recorded.

Asset Acquired in Exchange for Other Assets

When assets are acquired through exchange with other non-monetary assets or a combination of monetary and non-monetary assets, the asset acquired should be valued at the fair value of the assets given up. If this value cannot be reliably determined, then the fair value of the asset received should be used. Notice how this differs from the rule for share-based payments. The presumption is that the fair values of assets are generally more reliable than the fair values of shares.

The implication of this general rule is that when non-monetary assets are exchanged, there will likely be a gain or loss recorded on the transaction, as fair values and carrying values are usually not the same. The recognition of a gain or loss suggests that the earnings process is complete for this asset. This seems reasonable, as each company involved in the transaction would normally expect to receive some economic benefit from the exchange.

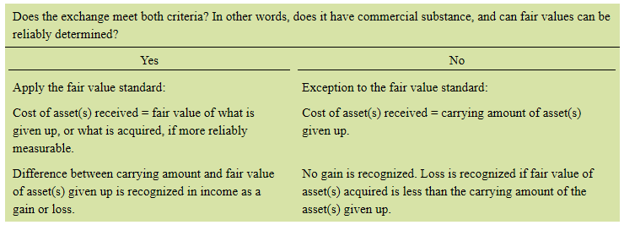

There are two instances, however, where the general rule does not apply. These two situations occur when:

- The fair values of both assets are not reliably measurable.

- The transaction lacks commercial substance.

Although it is an unusual situation, it is possible that the fair value of neither asset can be reliably determined. In this case, the asset acquired would be recorded at the book value of the asset given up. This means that no gain or loss would be recorded on the transaction.

A more likely situation occurs when the transaction lacks commercial substance. This means that after the exchange of the assets, the company’s economic position has not been altered significantly. This condition can usually be determined by considering the future cash flows resulting from the exchange. If the business is not expected to realize any difference in the amount, timing, or risk of future cash flows, either directly or indirectly, then there is no real change in its economic position. In this case, it would be unreasonable to recognize a gain, as there has been no completion of the earnings process. This type of situation could occur, for example, when two companies want to change their strategic directions, so they swap similar assets that may be located in different markets. There may be no significant difference in cash flows, but the assets received by each company are more suitable to their long-term plans. In this case, the asset acquired is reported at the carrying value of the asset given up.

One instance where accountants need to be careful occurs when an asset exchange lacks commercial substance and the carrying amount of the asset given up is greater than the fair value of the asset acquired. If we apply the principle for non-commercial exchanges by recording the asset acquired at the carrying value of the asset given up, the result will be an asset reported at an amount greater than its fair value. This result would create a misleading statement of financial position, so in this case, the asset acquired should be reported at its fair value, even though there is no commercial substance. This will result in a loss on the exchange.

A brief summary of the methods described above:

When following general standards of asset exchanges. Keep in mind a series of steps that need to happen when a transaction has commercial substance:

When following general standards of asset exchanges. Keep in mind a series of steps that need to happen when a transaction has commercial substance:

- Derecognize (remove from the accounts) the carrying value of the asset given up. Remember, the carrying value includes the cost of the asset AND accumulated depreciation.

- Recognize the fair value of the asset(s) received in exchange.

- Record the difference as a gain or loss in net income.

If the transaction lacks commercial substance, that is an exception to the fair value standard (applied to transactions that have commercial substance). So the approach is slightly different.

If a transaction lacks commercial substance, there again, steps that should be considered to record the transaction:

- Derecognize (remove from the accounts) the carrying value of the asset given up. Remember, the carrying value includes the cost of the asset AND accumulated depreciation.

- Recognize the carrying value of the asset(s) given up in exchange.

- Only record a loss in net income (never a gain).

When the transactions cash component is significant, there is less need to question if the transaction has commercial substance. As the amount of cash decreases, it’s likely that the transaction lacks commercial substance. One more important point regarding exchanges that lack commercial substance is to remember to check whether the fair value of the asset acquired it less than the cost assigned to it. Assets cannot be recognized at more than their fair value. If the fair value of the asset acquired is LESS than the cost assigned to it, the asset would have to be recorded at the lower fair value amount and a loss equal to the difference recorded.

Consider the following illustrations of asset exchanges.

Commercial Substance

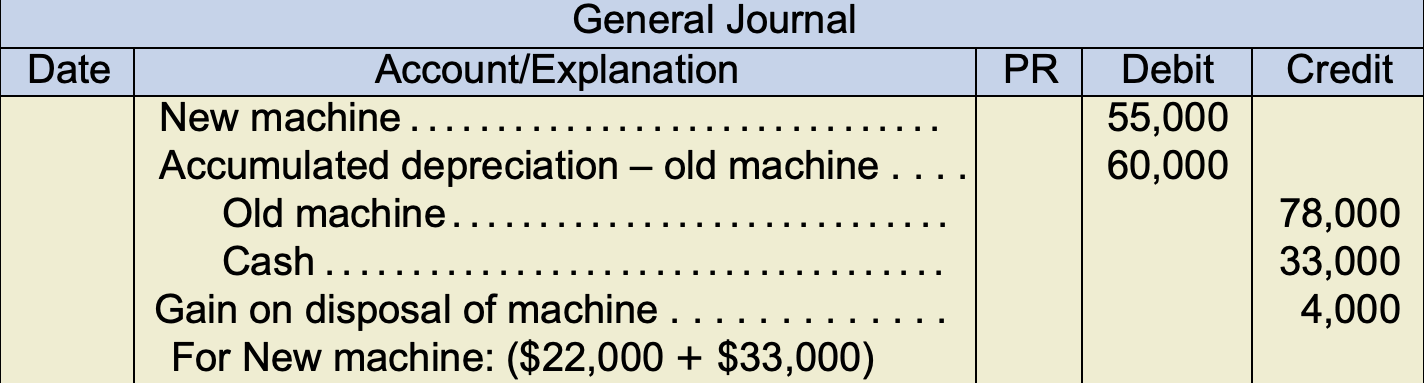

ComLink Ltd. decides to change its manufacturing process in order to accommodate a new product that will be introduced next year. They have decided to trade a factory machine that is no longer used in their production for a new machine that will be used to make the new product. The machine that is being disposed of had an original cost of $78,000 and accumulated depreciation of $60,000. The fair value of the old machine at the time of exchange was $22,000. The new machine being obtained has a list price of $61,000. After a period of negotiation, the seller finally agreed to sell the new machine to ComLink Ltd. for cash of $33,000 plus the trade-in of the old machine. As the new machine will be used to manufacture a new product for the company, and the old machine was essentially obsolete, we can reasonably conclude that this transaction has commercial substance. In this case, the journal entry to record the exchange will be:

Note that the new machine is reported at the fair value of the assets given up in the exchange ($33,000 cash + $22,000 machine). Also note that the gain on the disposal is equal to the fair value of the old machine ($22,000) less the carrying value of the machine at disposal ($78,000 − $60,000 = $18,000).

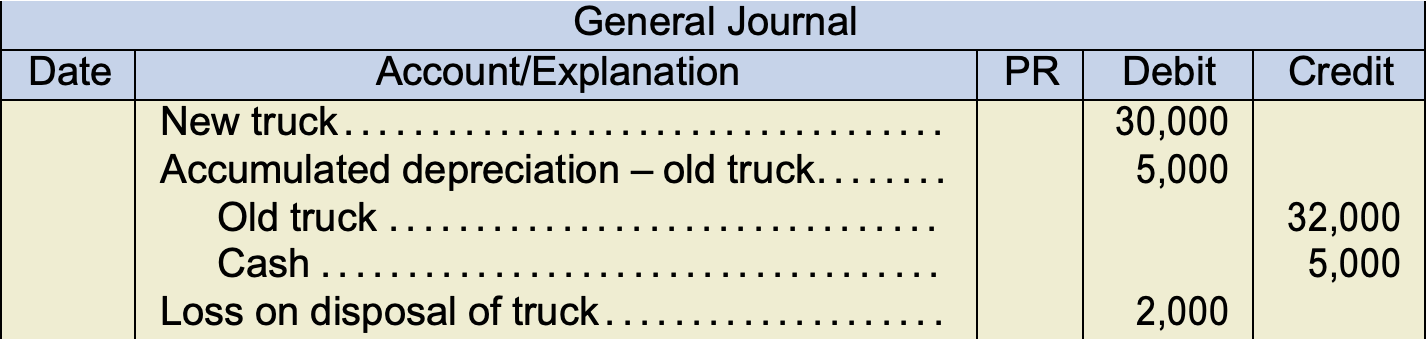

No Commercial Substance

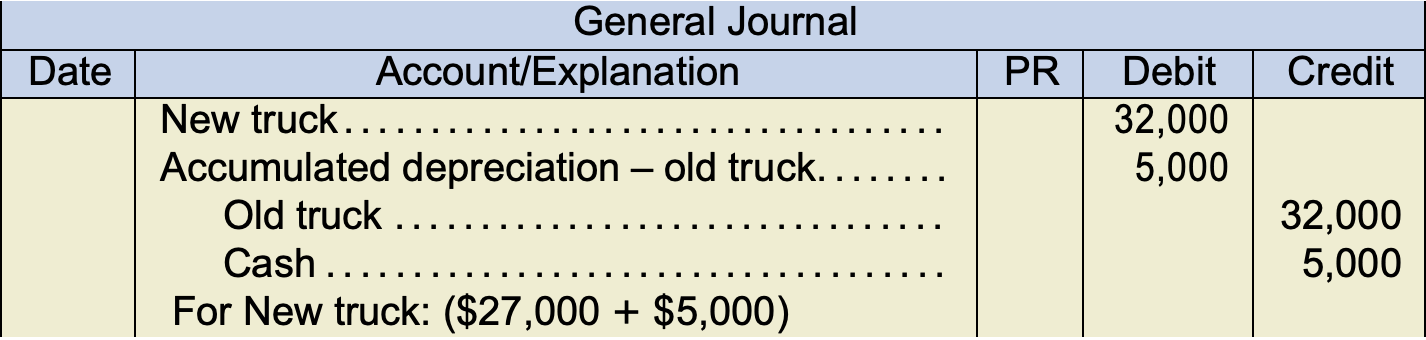

Assume that ComLink Ltd. has a delivery truck that it purchased one year ago for $32,000. Depreciation of $5,000 has been recorded to date on this asset. The company decides to trade this for a new delivery truck in a different colour. The new truck has the same functionality and expected life as the old truck. The only difference is the colour, which the company feels ties in better with its corporate branding efforts. No identifiable cash flows can be associated with the effect of this branding. The fair value of the old truck at the time of the trade was $28,000. The seller of the new truck agrees to take the old truck in trade, but requires ComLink Ltd. to pay an additional $5,000 in cash. In this instance, because there is no discernible effect on future cash flows, we would reasonably conclude that the transaction lacks commercial substance. The journal entry to record this transaction would be:

Note that the new truck is reported at the book value of the assets given up ($5,000 cash + ($32,000 − $5,000) = $27,000 truck). Also note that the implied fair value of the new truck ($28,000 + $5,000 = $33,000) is not reported, and no gain on the transaction is realized.

A slight twist to the above example:

If the same exchange occurred, but we were able to ascertain that the fair value of the asset acquired was only $30,000, it would be inappropriate to record the new asset at a value of $32,000, as this would exceed the fair value. The journal entry would thus be:

Note that the new truck is recorded at the lesser of its fair value and the book value of the asset given up. This results in a loss on the transaction, even though the transaction lacks commercial substance.

9.3.6. Deferred Payments

When a PPE asset is purchased through the use of long-term financing arrangements, the asset should initially be recorded at the present value of the obligation. This technique essentially removes the interest component from the ultimate payment, resulting in a recorded amount that should be equivalent to the fair value of the asset. (Note, however, that interest on self-constructed assets, covered in IAS 23 and discussed previously in this chapter, is included in the cost of the asset.) Normally, the present value would be discounted using the interest rate stated in the loan agreement. However, some contracts may not state an interest rate or may use an unreasonably low interest rate. In these cases, we need to estimate an interest rate that would be charged by arm’s length parties in similar circumstances. This rate would be based on current market conditions, the credit-worthiness of the customer, and other relevant factors.

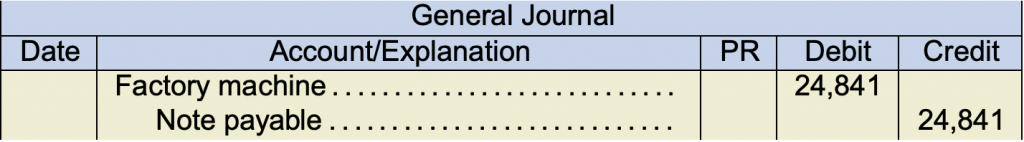

Consider the following example. ComLink Ltd. purchases a new machine for its factory. The supplier agrees to terms that allow ComLink Ltd. to pay for the asset in four annual instalments of $7,500 each, to be paid at the end of each year. ComLink Ltd. issues a $30,000, non-interest bearing note to the supplier. The market rate of interest for similar arrangements between arm’s length parties is 8%. ComLink Ltd. will record the initial purchase of the asset as follows:

The capitalized amount of $24,841 represents the present value of an ordinary annuity of $7,500 for four years at an interest rate of 8%. The difference between the capitalized amount and the total payments of $30,000 represents the amount of interest expense that will be recognized over the term of the note.

9.3.7. Government Grants

Governments will at times create programs that provide direct assistance to businesses. These programs may be designed to create employment in a certain geographic area, to develop research and economic growth in a certain industry sector, or other reasons that promote the policies of the government. When governments provide direct grants to businesses, there are a number of accounting issues that need to be considered.

IAS 20 states that government grants should be “recognized in profit or loss on a systematic basis over the periods in which the entity recognizes as expenses the related costs for which the grants are intended to compensate” (IAS 20-12, IAS, 1983). This type of accounting is referred to as the income approach to government grants, and is considered the appropriate treatment because the contribution is coming from an entity other than the owner of the business.

If the grant is received in respect of current operating expenses, then the accounting is quite straightforward. The grant would either be reported as other income on the statement of profit or loss, or the grant would be offset against the expenses for which the grant is intended to compensate. When the grant is received to assist in the purchase of PPE assets, the accounting is slightly more complicated. In this case, the company can defer the grant income, reporting it as a liability, and then recognize the income on a systematic basis over the useful life of the asset. Alternately, the company could simply use the grant funds received to offset the initial cost of the asset. In this method, the grant is implicitly recognized through the reduced depreciation charge over the life of the asset.

Consider the following example. ComLink Ltd. purchases a new factory machine for $100,000. This machine will help the company manufacture a new, energy-saving product. The company receives a government grant of $20,000 to help offset the cost of the machine. The machine is expected to have a five-year useful life with no residual value. The accounting entries for this machine would look like this:

| Deferral Method | Offset Method | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entries | Debit | Credit | Debit | Credit |

| Machine | 100,000 | 80,000 | ||

| Deferred grant | 20,000 | – | ||

| Purchase of machine | 80,000 | 80,000 | ||

| Depreciation expense | 20,000 | 16,000 | ||

| Accumulated depreciation | 20,000 | 16,000 | ||

| Deferred grant | 4,000 | – | ||

| Grant income | 4,000 | – | ||

| First year depreciation and revenue recognition.

For Depreciation expense, deferral method: ($100,000 ÷ 5 years = $20,000); offset method: ($80,000 ÷ 5 years = $16,000) For deferred grant: ($10,000 ÷ 5 years = $4,000) |

||||

The net effect on income of either method is the same. The difference is only in the presentation of the grant amount. Under the deferral method, the deferred grant amount presented on the balance sheet as a liability would need to be segregated between current and non-current portions.

Companies may choose either method to account for grant income. However, significant note disclosures of the terms and accounting methods used for grants are required to ensure comparability of financial statements.