5.3 Applications

IFRS 15 provides fourteen sections of application guidance which elaborate on certain aspects of the standard as they relate to specific situations. As well, the standard provides sixty-three illustrative examples for further clarity. In this section, we will examine some of the examples and guidance.

5.3.1. Bundled Sales

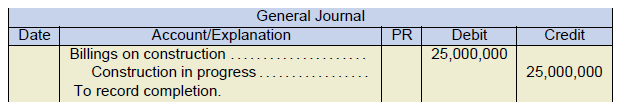

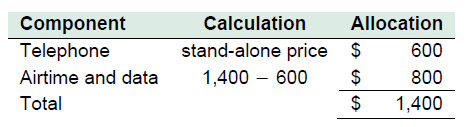

Telurama Inc. sells mobile telephones with two-year bundled airtime and data plans. The stand-alone selling price of the telephone is $600. The airtime and data plan does not have an observable stand-alone selling price, but Telurama has used the adjusted market assessment approach to estimate the stand-alone selling price as $1,000. As the mobile telephone business is very competitive, Telurama is required to sell the bundled package for $1,400. Telurama has determined that the discount should be allocated proportionally to the two performance obligations. In this case, the revenue would be recognized as follows:

If the airtime and data plan was sold to different customer groups for a broad range of different prices, Telurama could use the residual approach instead, as the stand-alone selling price for this performance obligation would not be observable. With this approach, the value of the observable stand-alone selling price (the telephone) is subtracted from the total contract value to arrive at the value of the unobservable stand-alone selling price (the airtime and data plan). In this example, Telurama would recognize revenue as follows:

In either case, revenue will be recorded based on the allocation calculated above. The revenue for the telephone will be recorded immediately upon delivery to the customer, and the remaining amount relating to the airtime and data will be reported as unearned revenue that will be recognized over the term of the contract. The journal entry at the time of sale to record this transaction using the first example would look like this:

5.3.2. Consignment Sales

Sometimes a retailer may not want to take the risk of purchasing a product for resale. The retailer may not want to tie up working capital or may think the product is too speculative or risky. In these cases, a consignment arrangement may be appropriate. Under this type of arrangement, the manufacturer of the product (the consignor) will ship the goods to the retailer (the consignee), but the manufacturer will retain legal title to the product. The consignee agrees to take care of the product and make efforts to the sell the product, but no guarantee of performance is made. As well, the agreement will likely require the return of the goods to the consignor after a specified period, if the goods are not sold. Thus, the performance obligation has not been satisfied when the goods are transferred to the consignee, and the consignor cannot recognize revenue at this point. The goods will, thus, remain on the consignor’s books as inventory until the consignee sells them. When the consignee actually sells the product, an obligation is now created to reimburse the consignor the amount of the sales proceeds, less any commissions and expenses that are agreed to in the contract for the consignment arrangement. At the time of sale, the consignor can recognize the revenue from the product, and the consignee can recognize the commission revenue.

Note that although the consignee has physical custody of the items for sale, the consignor still maintains ownership of those items. Therefore, the consigned inventory items remain on the books of the consignor, not the consignee. The consignee is acting as an agent on behalf of the consignor.

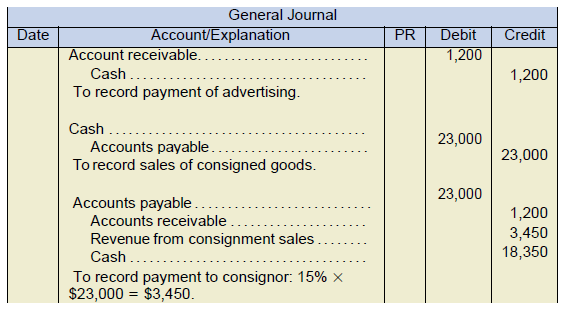

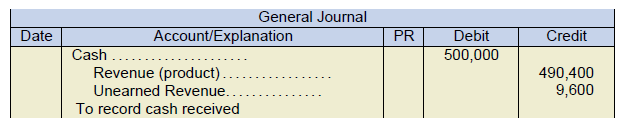

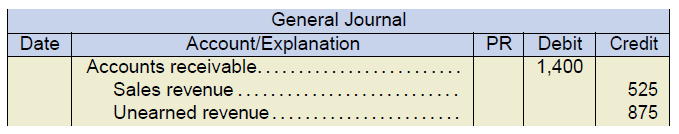

Assume the following facts: Dali Printmaking Inc. produces fine-art posters. Dali ships 3,000 posters to Magritte Merchandising Ltd. on a consignment basis. The total cost of the posters is $12,000, and Dali pays $550 in shipping costs. Magritte pays $1,200 for advertising costs that will be reimbursed by Dali. During the year, Magritte sells one-half of the posters for $23,000. Magritte informs Dali of this and pays the amount owing. Magritte’s commission is 15 percent of the sales price. The accounting for this type of transaction looks like this:

Dali Printmaking Inc. (consignor)

Magritte Merchandising Ltd. (consignee)

It’s very important to remember. The consignor maintains ownership of the items and those items remain on the books of the consignor, even though the consignor does not have physical possession.

5.3.3. Sales With Right of Return

It is a common practice in the retail sector to allow customers to return products for various reasons, within a certain period of time. When the product is returned, the customer may receive a full refund, a credit to be applied against future purchases, or a replacement product. The accounting issue for the company is whether the full amount of revenue should be recognized at the time of sale, given that a certain number of returns may be expected. The general approach used here is to record revenue only in the amount of consideration expected to be received. In other words, the company needs to make an estimate at the time of sale of the amount of returns expected, and then exclude this amount from reported revenue. This amount should be reported as a refund liability. As well, the company should report an asset equal to the expected amount of product to be returned. The asset would be adjusted against the cost of goods sold in the period of sale. At the end of every accounting period, the estimates used to arrive at the refund liability and asset should be reviewed and adjusted where necessary. It is expected that most companies should be able to make reasonable estimates of these amounts, using historical, industry, technical, or other data.

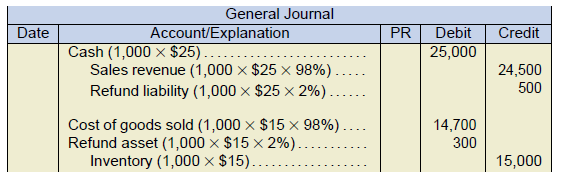

Consider the following example. Wyeth Mart sells high quality paintbrushes for use in fine art applications. Each brush costs the company $15 and sells for $25. Wyeth Mart offers a full refund for any unused product that is returned within 30 days of purchase, and the company expects that these returned products can resold for a profit. The company has reviewed historical sales data and estimated that 2% of products sold will be returned for a refund. During the month of May, 1,000 paintbrushes are sold for cash. The journal entries in May would be:

In June, if 20 brushes are returned, the journal entry will be:

If the amount returned differs from estimated amount, the refund liability and refund asset will need to be adjusted once the return period expires. This is an ongoing process, as most companies will continue to make new sales during the period. As a practical matter, many companies will only review the balances of the refund liability and refund asset account at the annual reporting date.

5.3.4. Bill-and-Hold Arrangements

There are times when a customer may purchase goods from a company, but not take physical possession of the goods until a later date. Customers may have legitimate reasons for doing this, including a lack of warehouse space, delays in their own productions processes, or the need to secure a supply of a scarce product. When the selling entity is considering whether to recognize revenue on these types of contracts, it needs to consider if control of the goods has been transferred to the customer. Aside from the normal criteria that are used to evaluate control, an additional three conditions must be satisfied in bill- and-hold transactions:

- The reason for the bill-and-hold transaction must be substantive;

- The product must be identified separately;

- The entity must not have the ability to use or resell the product to another customer.

(CPA Canada Handbook – Accounting, IFRS 15.B81)

Consider the following example. Koenig Ltd. processes rare-earth elements used in certain technological applications. One of these elements forms a critical component of a customer’s product. The customer has requested Koenig Ltd. set aside a one-year supply of the element to ensure that its production process is not interrupted. The customer’s factory is in close proximity to Koenig’s warehouse, and transportation between the two locations is easily facilitated. The customer agrees to pay for the entire one-year supply, as well as a monthly rental fee to cover Koenig’s cost of storing the product in its warehouse. The entire payment of $500,000, representing the cost of the element and 12 months of rent, is received on December 29, 2022. Koenig has separately identified and segregated the product in its warehouse, and the contract with the customer specifies that product cannot be sold to another customer. The fair value of the warehouse rental service being provided is $800 per month.

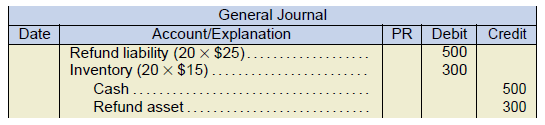

In this case, the revenue from the sale of the product can be recognized on December 29, 2022 because the reason for the bill-and-hold transaction is substantive (the customer requested it), the product has been identified separately, and the contract specifies that the product cannot be resold. Assuming the transaction price has been determined using the fair value of the product and rental service, revenue will be recognized as follows:

Revenue related to rental service ($800 × 12) = $9,600

Revenue related to product ($500,000 − $9,600) = $490,400

Thus, on December 29, 2022, Koenig will recognize revenue of $490,400 and report unearned revenue of $9,600. The $9,600 will be recognized as revenue at the rate of $800 per month over the next year. If the holding period were longer than one year, Koenig would also need to consider the presence of a financing component in the transaction price.

Therefore, the journal entry that Koenig will record at December 29, 2022:

5.3.5. Barter Transactions

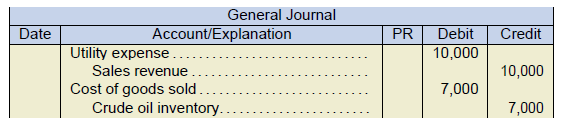

When a customer and an entity agree that payment for goods or services can be made using non-cash consideration, the non-cash consideration received should be reported at its fair value. Assume that an oil-and-gas company wishes to trade a quantity of crude oil for natural gas that is used to power the refinery where the oil is processed. The natural gas will be consumed and will not be held in inventory. As these two products have different uses for the company, this transaction has commercial substance. Assume that the fair value of the natural gas received is $10,000, and the cost of the crude oil traded is $7,000. The journal entry for this transaction would be as follows:

5.3.6. Long-Term Construction Contracts

Many large construction projects can take several years to complete. With these types of projects, a significant amount of professional judgment is required to determine when to recognize revenue. An obvious approach may be to simply wait until the completion of the project before recognizing revenue. However, this approach would not properly reflect the periodic activities of the business. Although contracts of this nature are usually complex, they do usually establish the right of the contractor to bill for work that is completed throughout the project and result in a transfer of control to the customer. Because the contractor is adding economic value to the product, while at the same time establishing a legal right to collect money for work performed, it is appropriate to recognize revenue on a periodic basis throughout the life of the project. This method of recognizing revenue and related costs is referred to as the percentage-of-completion method.

The most difficult part of applying this method is determining the proportion of revenue to recognize at the end of each accounting period. Both inputs (labour, materials, etc.) and outputs (square footage of a building completed, sections of a bridge, etc.) can be used, but judgment must be applied to determine which approach results in the most accurate measurement of progress on the project. One of the problems with output methods is that the measure may not accurately represent the entity’s progress toward satisfying the performance obligation. With input methods, the problem may be that the input measured does not directly correlate to the transfer of control of goods or services to the customer. A common approach that is used by many construction companies is called the cost- to-cost basis. This approach uses the dollar value of inputs as the measurement of progress. More precisely, the proportion of costs incurred to date to the current estimate of total project costs is multiplied by the total expected revenue on the project to determine the amount of revenue to recognize. When this method is used, it is assumed that costs incurred do correlate to the transfer of control of goods and services to the customer and that these costs are a reasonable representation of the entity’s progress toward satisfying the performance obligation. This approach is illustrated in more detail in the examples below.

The key item to remember with the percentage-of-completion method to revenue recognition is that a portion of revenue is recognized each period, based on costs. The following formulas will help:

P = CM

NOTE – costs incurred to date are the actual costs incurred on the project. The most recent estimate of TOTAL costs includes the costs incurred as well as estimated costs to complete the project. Remember, companies are estimating costs to complete, that means the total costs from year-to-year could possibly change – because companies are estimating costs based on current information. In the final year of a project, the percent complete should equal 100%.

Revenue to be recognized to date = Percent complete × Estimated total revenue

NOTE – revenue to date is for the amount of time working on the project. One more step is required in order to determine revenue for the current year:

Current-period revenue = Revenue to be recognized to date − Revenue recognized in a prior period

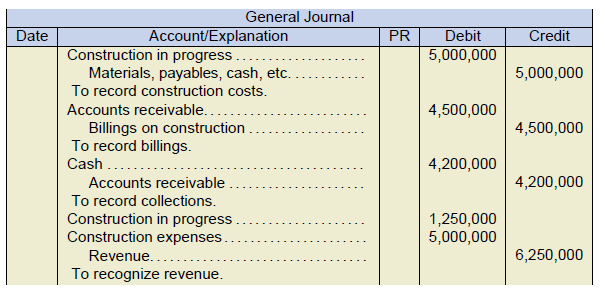

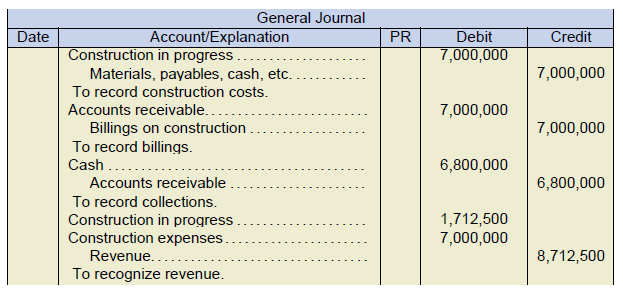

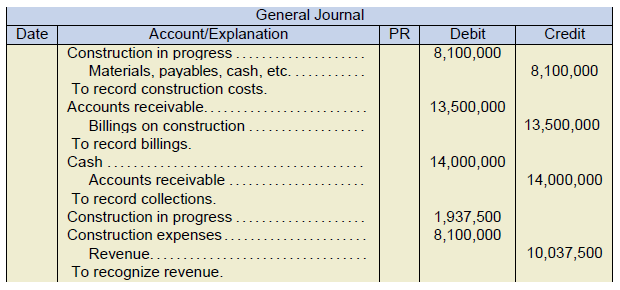

Example 1: Profitable Contract

Salty Dog Marine Services Ltd. commenced a $25 million contract on January 1, Y1, to construct an ocean-going freighter. The company expects the project will take three years to complete. The total estimated costs for the project are $20 million. Assume the following data for the completion of this project:

| Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Costs to date | 5,000,000 | 12,000,000 | 20,100,000 |

| Estimated costs to complete project | 15,000,000 | 8,050,000 | |

| Progress billings during the year | 4,500,000 | 7,000,000 | 13,500,000 |

| Cash collected during the year | 4,200,000 | 6,800,000 | 14,000,000 |

The amount of revenue and gross profit recognized on this contract would be calculated as follows:

| Y1 | Y2 | Y3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Costs to date (A) | 5,000,000 | 12,000,000 | 20,100,000 |

| Estimated costs to complete project | 15,000,000 | 8,050,000 | 0 |

| Total estimated project costs (B) | 20,000,000 | 20,050,000 | 20,100,000 |

| Percent complete (C = A ÷ B) | 25.00% | 59.85% | 100.00% |

| Total contract price (D) | 25,000,000 | 25,000,000 | 25,000,000 |

| Revenue to date (C ×D) | 6,250,000 | 14,962,500 | 25,000,000 |

| Less previously recognized revenue | (6,250,000) | (14,962,500) | |

| Revenue to recognize in the year | 6,250,000 | 8,712,500 | 10,037,500 |

| Costs incurred the year | 5,000,000 | 7,000,000 | 8,100,000 |

| Gross profit for the year | 1,250,000 | 1,712,500 | 1,937,500 |

Note that the costs incurred in the year are simply the difference between the current year’s costs to date and the previous year’s costs to date. The total amount of gross profit recognized over the three-year contract is $4,900,000, which represents the difference between the contract revenue of $25 million and the total project costs of $20.1 million. It is not uncommon for the total project costs to differ from the original estimate. Adjustments to estimated project costs are always captured in the current year only. It is assumed that estimates are based on the best information at the time they are made, so it would be inappropriate to adjust previously recognized profit.

The journal entries to record these transactions in Year 1 (Y1) would look like this:

The journal entries to record these transactions in Year 2 (Y2) would look like this:

The journal entries to record these transactions in Year 3 (Y3) would look like this:

Construction in progress is a balance sheet account that represents accumulated costs to date on a project plus any recognized profit. Billings on construction is also a balance sheet account; it represents total amounts billed to the customer. These two accounts are normally presented on a net basis on the balance sheet, and may sometimes be described as Contract Asset/Liability. If construction in progress exceeds billings on construction, the net balance would be reported as recognized revenues in excess of billings. This asset would be reported as either current or noncurrent, depending on the length of the contract. If billings on construction exceeds construction in progress, the net balance would be reported as billings in excess of recognized revenues. This liability would also be either current or noncurrent. On the income statement, the company would report the revenues and construction expenses, with the difference being reported as gross profit.

Accounts receivable you notice has a zero ($0) balance at the end of the contract. That makes sense at the customer should be paying as they work through the project. Note that progress billings are a way to help and manage cash flow. Progress billings do not necessarily correspond to revenue.

In Year 3 (Y3), once the contract is completed, an additional journal entry is required to close the billings on construction and construction in progress accounts:

Example 2: Unprofitable Contract

Although it would be ideal if contract costs could always be accurately estimated, most often this is not the case. Unexpected difficulties can occur during the construction process, or costs can rise due to uncontrollable economic factors. Whatever the reason, it is quite likely that the actual total costs on the project will differ from the original estimates. If costs rise during an accounting period, this situation is treated as a change in estimate, as it is presumed that the original estimates were based on the best information available at the time. A change in estimate is always applied on a prospective basis, which means the current period is adjusted for the net effect of the change, and future periods will be accounted for using the new information. There is no need to restate the prior periods when there is a change in estimate. If the revised estimate of costs will still result in the contract earning an overall profit, the only effect of increased cost estimates will be to reverse any previously overaccrued profits into the current year. This may result in a loss for the current year, but the project will still report a total profit over its lifespan.

Sometimes, however, cost estimates may increase so much that the total project becomes unprofitable. That is, the total revised project costs may exceed the total revenue on the project. This situation is referred to as an onerous contract, which results in a liability. When the unavoidable costs of fulfilling a contract exceed the economic benefits to be derived from the contract, a conservative approach should be applied, and the total amount of the expected loss should be recorded in the current year. In determining the unavoidable costs on the contract, the entity should consider the least costly option available, even if this means cancelling the contract and paying a penalty. This treatment is required because it is important to alert financial-statement readers of the potential total loss, regardless of the stage of completion, so that they are not misled about the realizable value of assets or income. Onerous contracts will be discussed in a later chapter.

To illustrate this situation, consider our Salty Dog example again, with one change. Assume that in 2021, due to a worldwide iron shortage, the expected costs to complete the project rise from $8,050,000 to $18,000,000. However, in 2022, it turns out that the drastic rise in iron prices was only temporary, and the final tally of costs at the end of the project is $26,500,000. The profit on the project would be calculated as follows:

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Costs to date (A) | 5,000,000 | 12,000,000 | 20,100,000 |

| Estimated costs to complete project | 15,000,000 | 18,000,000 | 0 |

| Total estimated project costs (B) | 20,000,000 | 30,000,000 | 26,500,000 |

| Percent complete (C = A ÷ B) | 25.00% | 40.00% | 100.00% |

| Total contract price (D) | 25,000,000 | 25,000,000 | 25,000,000 |

| Revenue to date (C ×D) | 6,250,000 | 10,00,000 | 25,000,000 |

| Less previously recognized revenue | (6,250,000) | (14,500,000) | |

| Revenue to recognize in the year | 6,250,000 | 3,750,000 | 15,000,000 |

| Costs incurred the year | 5,000,000 | 7,000,000 | 14,500,000 |

| Gross profit (loss) for the year | 1,250,000 | (3,000,000) | 500,000 |

| Additional loss to recognize[1] | (3,000,000) | 3,000,000 | |

| Gross profit (loss) for the year | (6,250,000) | 3,500,000 |

Notice that the total loss recognized over the life of the project is $1,500,000, which reconciles with the total project revenue of $25,000,000 minus total project costs of $26,500,000. Also, the journal entries would be similar to those indicated above.

Other Considerations

There may be cases where input costs include the purchase of a single, significant asset. The entity may be required to install the asset as part of the contract, but may not have anything to do with the construction of the asset itself. In this case, the use input costs may be a misleading way to measure progress toward satisfaction of the performance obligation, as the entity does not contribute to the construction of the asset.

Consider the following example. Rohe Construction Ltd. signs a contract with a customer to install a distillation tower in an oil refinery. Rohe Construction Ltd. purchases the distillation tower from a supplier for $3,000,000 and delivers it to the work site on November 20, 2022. At this time, the customer obtains control of the tower. The company estimates that it will take six months to install the distillation tower, and that the total project costs, excluding the tower, will be $1,200,000. The total value of the contract is $5,000,000.

The company has determined that using total input costs would be a misleading way to represent its progress toward satisfying the performance obligation. Instead, it will recognize revenue from the distillation tower itself using the zero-margin method, and revenue from the installation services using the percentage-of-completion method. Assume that by December 31, 2022, the company has incurred $300,000 of costs, excluding the purchase of the tower. Revenue would be recognized as follows:

| Tower | Installation | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue | 3,000,000 | 500,000 | 3,500,000 |

| Cost of goods sold | 3,000,000 | 300,000 | 3,300,000 |

| Gross profit | 0 | 200,000 | 200,000 |

NOTE: Installation revenue is calculated as ($5,000,000 − $3,000,000) × ($300,000 ÷ $1,200,000)

Using this approach, the total profit recorded to date of $200,000 represents 25% of the total expected project profit of $800,000 ($5,000,000 − $3,000,000 − $1,200,000). This makes sense, as the company has incurred 25% of the total expected costs, excluding the tower itself. The company doesn’t recognize profit from the tower itself, as the tower’s delivery does not represent satisfaction of the company’s performance obligation to install the tower.

The zero-margin method can also be applied in situations where it is difficult to measure the outcome of a performance obligation. This could occur, for example, in the early stages of a long-term construction contract where significant progress cannot yet be measured. If the entity believes that costs incurred will ultimately be recoverable under the contract, then the zero-margin method can be applied, and the company will recognize revenue equal to the costs incurred. Once the entity determines that progress is now reliably measurable, it can then start applying the percentage-of-completion method.

- Note: The additional loss to recognize in 2021 represents the loss expected at this point on work not yet completed (i.e., 60%x[25,000,000-30,000,000]). This additional loss gets reversed in 2022, because there is no further work to complete once the project is finished. By recognizing this additional amount in 2021, the financial statements will show the total expected loss on the project at this point. In 2021, the additional loss will be journalized by adding it to the total of the construction expenses account recognized. ↵

![Component: telephone calculation: [600 divided by (600 + 1000)] times 1400 allocation: $525 component: airtime and data calculation: [1000 divided by (600 + 1000)] times 1400 allocation: $875 total: 1400](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1911/2021/09/gj20.png)

![General Journal. To segregate consignment goods. Inventory on consignment 12,000 under debit. Finished goods inventory 12,000 under credit. To record freight: Inventory on consignment 550 under debit Cash 550 under credit. To record receipt of net sales. Cash 18,350 under debit. Advertising expense 1,200 under debit. Commissions expense (15% x $23,000) 3,4500 under debit. Consignment revenue 23,000 under credit. To record COGS: [(12,000 + 500) x 50%]. Cost of goods sold 6,275 under debit Inventory on consignment 6,275 under credit.](https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/1911/2021/09/gj23.png)