10.7 Appendix A: ASPE Standards for Impairment

Under ASPE 3063, a different set of standards is applied to the issue of PPE impairment. This model is referred to as the cost recovery impairment model. The basic premise underlying these principles is that an asset is impaired if its carrying value cannot be recovered. Unlike IFRS, which requires annual impairment testing, the ASPE standard requires only impairment testing when events or changes in circumstances indicate that impairment may be present. Some of the possible indicators of an asset’s impairment include the following:

- A significant decrease in its market price

- A significant adverse change in the extent or manner in which it is being used or in its physical condition

- A significant adverse change in legal factors or in the business climate that could affect its value, including an adverse action or assessment by a regulator

- An accumulation of costs significantly in excess of the amount originally expected for its acquisition or construction

- A current-period operating or cash flow loss combined with a history of operating or cash flow losses or a projection or forecast that demonstrates continuing losses associated with its use

- A current expectation that, more likely than not, it will be sold or otherwise disposed of significantly before the end of its previously estimated useful life (“more likely than not” means a level of likelihood that is more than 50 percent) (CPA Canada, 2016, 3063.10).

The accountant will need to apply judgment in assessing these criteria. Other factors could be present that could indicate impairment.

Once the determination is made that impairment may be present, the accountant must follow a two-step process:

- Determine if the asset is, in fact, impaired.

- Calculate and record the impairment loss.

Step 1 involves the application of a recoverability test. This test is applied by comparing the predicted, undiscounted future cash flows from the asset’s use and ultimate disposal with the carrying value of the asset. If the undiscounted future cash flows are less than the asset’s carrying value, the asset is impaired. The calculation of the predicted, undiscounted cash flows will be based primarily on the company’s own assessment of the possible uses of the asset. However, the accountant will need to apply diligence in assessing the reasonableness of these cash flow assumptions.

Step 2 involves a different calculation to then determine the impairment loss. The impairment loss is the difference between the asset’s carrying value and its fair value. The fair value is defined as “the amount of the consideration that would be agreed upon in an arm’s length transaction between knowledgeable, willing parties who are under no compulsion to act” (CPA Canada, 2016, 3063.03b). Note that, unlike the IFRS calculation, disposal costs are not considered. The fair value should always be less than the undiscounted cash flows, as any knowledgeable party would discount the cash flows when determining an appropriate value. The best evidence of fair value would be obtained from transactions conducted in active markets. However, for some types of assets, active market data may not be available. In these cases, other techniques and evidence will be required to determine the fair value.

To summarize the steps:

- Determine if impairment exists by comparing the future undiscounted cash flow (UDCF) to the carrying value (if UDCF < CV) there is impairment. NOTE – this is NOT the impairment calculation, this step is needed to determine if impairment exists.

- To determine the impairment, compare the fair value of the asset to the carrying value (if FV < CV) that is the amount of impairment.

The application of this standard can be best illustrated with an example. Consider a company that believes a particular asset may be impaired, based on its current physical condition. Management has estimated the future undiscounted cash flows from the use and eventual sale of this asset to be $125,000. Recent market sales of similar assets have indicated a fair value of $90,000. The asset is carried on the books at a cost of $200,000 less accumulated depreciation of $85,000. In applying step 1, the recoverability test, management will compare the undiscounted cash flows ($125,000) with the carrying value ($115,000). In this case, because the undiscounted cash flows exceed the carrying value, no impairment is present, and no further action is required.

If, however, the future, undiscounted cash flows were $110,000 instead of $125,000, the result would be different:

| Step 1 | Future undiscounted cash flows | $110,000 |

|---|---|---|

| Carrying value | $115,000 | |

| Difference | $(5,000) |

Because this result is less than zero, the asset is impaired. The impairment loss must then be calculated.

| Step 2 | Fair value | $90,000 |

|---|---|---|

| Carrying value | $115,000 | |

| Impairment loss | $(25,000) |

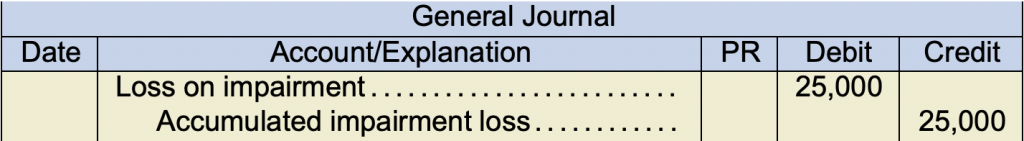

This loss would be recorded as follows:

Although a separate accumulated impairment loss account has been credited here, it is common in practice to simply credit accumulated depreciation. The net result of these two approaches will be the same.

The new carrying value for the asset after the impairment loss is recorded becomes the new cost base for the asset. This result has two effects. First, the asset’s depreciation rate will need to be recalculated to take into account the new cost base and any other changes that may be relevant. Second, any subsequent change in circumstances that results in the asset no longer being impaired cannot be recorded. Future impairment reversals are not allowed, because we are creating a new cost base for the asset.

NOTE – reversal of an impairment change is NOT permitted under ASPE.

One conceptual problem with this approach is that the carrying value of the asset may not always reflect the underlying economic value to the company. By not testing for impairment every year, it is possible that an asset that is becoming impaired incrementally may not be properly adjusted until the impairment is quite severe. Once the impairment is recorded, the inability to reverse this amount if future circumstances improve means the asset’s economic potential is not properly reflected on the balance sheet. Although there are problems with this approach, it can be argued that annual impairment testing for all assets is a time-consuming and costly exercise. Thus, the standard results in a trade-off between theoretical and practical considerations. This is considered a reasonable trade- off for private enterprises, as they usually have a much smaller group of potential financial- statement readers, as well as fewer resources available to dedicate to accounting and reporting matters.