10.3 Impairment

For a variety of reasons, a PPE asset may sometimes become fully or partially obsolete to the business. If the value of the asset declines below its carrying value, the accounting question is whether this decline in value should be recorded or not. For current assets such as inventory, these types of declines in value are recorded so that a financial- statement reader is not misled into thinking the current asset will generate more cash than is actually realizable. This treatment is reasonable for a current asset, but should the same approach be used for PPE assets?

Impairment of PPE asset values can result from many different circumstances. IAS 36 discusses the following possible signs of impairment:

External indicators

- include observable indications of decline in value;

- include technological, market, economic, or legal changes that affect the asset or entity;

- include increases in interest rates that reduce the discounted value in use of the asset; and

- mean that the carrying value of the entity’s net assets is greater than its market capitalization.

Internal indicators

- include obsolescence or physical damage;

- include significant changes in how the asset is used, such as excess capacity or plans for early disposal of the asset; and

- mean that economic performance of asset is worse than expected, including the cash needed to acquire and/or operate and maintain the asset.

These factors and other information will need to be considered carefully when reviewing for impairment; judgment will need to be applied. The company should assess whether there is any indication of asset impairment on an annual basis. If there is evidence of impairment, then the company will need to determine the amount of the impairment and account for this condition.

We will consider two methods of accounting for impairment:

IFRS – see section 10.3.1 – Rational Entity Impairment Model

ASPE – see section 10.7 – Cost Recovery Impairment Model

10.3.1. Accounting for Impairment (IFRS)

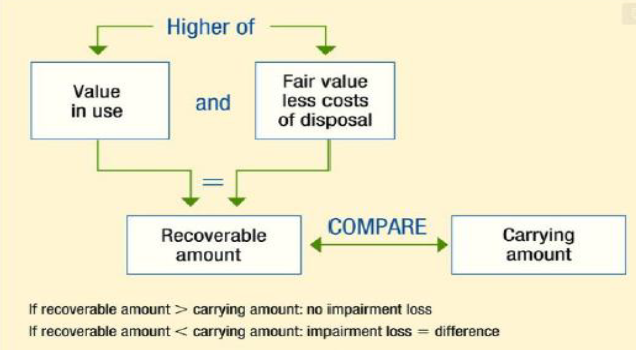

There is an assumption in the IFRS standards that an entity will act in a rational manner. The rational entity impairment model follows IFRS. This means that if selling the asset rather using it can generate more economic benefit, it would make sense to do so. To determine impairment, we need to compare the carrying value of the asset with its recoverable amount.

As indicated in the diagram above, the recoverable amount of an asset is defined as the greater of the asset’s value in use and its fair value, less costs of disposal. The asset’s value in use is calculated as the present value of all future cash flows related to the asset, assuming that it continues to be used. The fair value less costs of disposal refers to the actual net amount that the asset could be sold for based on current market conditions.

Consider the following example. During the annual review of asset impairment conditions, a company’s management team decides that there is evidence of impairment of a particular asset. This asset is recorded on the books with a cost of $30,000 and accumulated depreciation of $10,000. Management estimates and discounts future cash flows related to the asset and determines the value in use to be $15,000. The company also seeks the advice of an equipment appraiser who indicates that the asset would likely sell at an auction for $14,000, less a 10 percent commission.

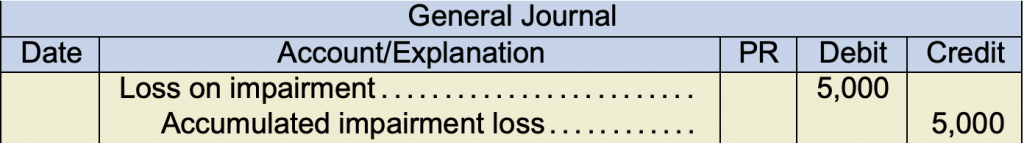

The recoverable amount of the asset is $15,000, as this value in use is greater than the fair value less costs of disposal ($14,000 − $1,400 = $12,600). The carrying value is $20,000 ($30,000 − $10,000). As the recoverable amount is less than the carrying value, the asset is impaired. The following journal entry must be recorded to account for this condition:

Although a separate accumulated impairment loss account has been credited here, it is common in practice to simply credit accumulated depreciation. The net result of these two approaches will be exactly the same. Also note that if the asset were accounted for using the revaluation method, the impairment loss would first reduce any existing revaluation surplus (OCI), with the remaining loss being charged to the income statement. The loss on impairment flows through the income statement to calculate net income. Accumulated impairment loss is a contra-asset on the balance sheet which will impact the net realizable value (carrying value) of the asset.

If, in the future, the recoverable amount increases so that the asset is no longer impaired, the accumulated impairment loss can be reversed. However, the impairment loss can be reversed only to the extent that the new carrying value does not exceed the depreciated carrying value that would have existed had the impairment never occurred. Also note that in subsequent years, depreciation calculations will be based on the revised carrying value.

A different method is used to determine impairment under ASPE. This method is described in 10.7 Appendix A.

10.3.2 Cash-Generating Units

The usual situation when applying an impairment test would be to make the assessments on an asset-by-asset basis. However, in some circumstances, it may be impossible to determine the impairment of an individual asset. Some assets may have a value in use only when used in combination with other assets. Consider, for example, a petrochemical- processing plant. The plant is engineered with many customized components that work together to process and produce a final product. If any part of the plant were removed, the process could not be completed. In this case, the cash flows derived from the use of the group of assets are considered a single economic event. The cash flows from an individual asset component within the group cannot be determined separately. In these cases, IAS 36 allows the impairment test to be performed at the level of the cash- generating unit, rather than at the individual asset level.

IAS 36 defines a cash-generating unit as “the smallest identifiable group of assets that generates cash inflows that are largely independent of the cash inflows from other assets or groups of assets” (International Accounting Standards, n.d., 36.68). The definition of cash-generating units should be applied consistently from year to year. Obviously, significant judgment is required in making these determinations.

The impairment test is applied the same way to cash-generating units as with individual assets. The only difference is that any resulting impairment loss is allocated on a pro-rata basis to the individual assets within the cash-generating unit, based on the relative carrying amounts of those assets within the group. However, in this process, no individual asset should be reduced below the greater of its recoverable amount or zero.

Consider the following example. A petrochemical-processing plant is composed of a number of different assets, including the following:

| Asset | Cost ($) | Accumulated Depreciation ($) | Carrying Amount ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pumps, tanks, and drums | 390,000 | 210,000 | 180,000 |

| Reactors | 1,100,000 | 650,000 | 450,000 |

| Pipes and fittings | 275,000 | 155,000 | 120,000 |

| Distillation column | 850,000 | 465,000 | 385,000 |

| 2,615,000 | 1,480,000 | 1,135,000 |

Management considers this plant to be a cash-generating unit. Due to recent declines in commodity prices, management believes the plant may be impaired. After some investigation, management determines that the distillation column could be sold for net proceeds of $435,000. All the other assets, however, are integrated into the plant structure and could not be sold separately. As well, due to local regulations, the plant cannot be sold in its entirety. Management has projected that by operating the plant for the next three years, cash flows of $1,200,000 could be generated. The present value of these cash flows is $950,000.

Impairment here is determined by comparing the carrying amount of $1,135,000 with the recoverable amount of $950,000. The value in use is the appropriate measure here, as the fair value less costs to sell of $435,000 is lower. In this case, there is an impairment of $185,000 ($1,135,000 − $950,000). None of the impairment should be allocated to the distillation column, as the carrying value of $385,000 is already less than the recoverable amount of $435,000. For the remaining components, we cannot determine the recover- able amount, so the impairment loss will be allocated to these assets on a pro-rata basis.

| Asset | Carrying Amount($) | Proportion | Impairment Loss ($) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pumps, tanks, and drums | 180,000 | 180/750 | 44,400 |

| Reactors | 450,000 | 450/750 | 111,000 |

| Pipes and fittings | 120,000 | 120/750 | 29,600 |

| 750,000 | 185,000 |

The journal entry would record separate accumulated-impairment loss amounts for each of the above components.