5.2 Revenue Recognition

There are two different perspectives on how to recognize revenues:

- The contract-based approach (asset-liability approach)

- The earnings approach

The contract-based approach is the subject of IFRS 15 – Revenue from Contracts with Customers. This standard focuses on the contractual rights and obligations of the buyer and the seller. The earnings approach is currently used in ASPE. This approach focuses on the process of adding value to the final product or service that is delivered to the customer, and will be discussed in Section 5.5.

The main differences between the approaches:

The contract-based (asset-liability) approach recognizes and measures revenue based on changes in assets and liabilities.

The earnings approach recognizes and measures revenue based on whether it has been earned.

IFRS 15, issued in 2014, is effective for fiscal years beginning on or after January 1, 2018, although early adoption is allowed. The length of this transition period reflects the anticipated effect this standard may have on business results and business processes. This standard was a joint project between IASB and FASB, as both standard-setting bod- ies were interested in creating more consistency in the application of revenue-recognition principles. The nature and complexity of this standard and the resulting process meant that development time was lengthy. The project was first added to the IASB agenda in 2002, and the first discussion paper was produced in 2008.

The standard applies to all contractual relationships with customers except for leases, financial instruments, insurance contracts, and those transactions covered by standards that deal with subsidiaries, joint arrangements, joint ventures, and associates. The standard also doesn’t apply to non-monetary exchanges between entities in the same line of business to facilitate sales to customers or potential customers. The new standard replaces several existing standards, including IAS 11, IAS 18, IFRIC 13, IFRIC 15, IFRIC 18, and SIC-31.

Under the IFRS 15 approach asset-liability approach, companies should account for revenue based on the asset or liability arising from contracts with customers. We want to be sure that the asset and liability are correctly stated. Also recall the revenue recognition principle which states that a company should recognize revenue in the accounting period when the performance obligation is satisfied.

The standard takes the approach that the essence of the relationship between a business, and its customers can be characterized as one of contractual rights and obligations. To determine the correct accounting treatment for these transactions, the standard applies a five-step model:

- Identify the contract(s) with a customer.

- Identify the performance obligations in the contract.

- Determine the transaction price.

- Allocate the transaction price to the performance obligations in the contract.

- Recognize revenue when (or as) the entity satisfies a performance obligation.

The standard provides a significant amount of detail in the application of these steps. We will focus on some of the key elements of each component of the model. An important point to remember regarding the five steps listed above. The steps may happen simultaneously. They do not necessarily have to happen in sequence.

5.2.1. Identify the Contract

The contract must be approved by both parties and must clearly identify both the goods and services that will be transferred and the price to be paid for these goods and services. The contract must be one of commercial substance, and there must be reasonable expectation that the ultimate amount owing from the customer will be collected. This collectability criterion will prevent a situation where revenue is recognized and then a provision is immediately made for an uncollectible account. Under this criterion, the contract cannot be recognized until the collection is probable. If these conditions are not present, the contract can be continually reassessed to see if its status changes. The standard also applies guidance on how to deal with contract modifications. Depending on the circumstances, the modifications may be treated as either a change to the existing contract or as a completely new contract. A new contract would exist if the scope of the contract increases due to the addition of distinct goods or services, and the price of the contract increases by an amount that reflects the entity’s stand-alone selling prices of the additional goods or services.

The contract will not exist if each party to the contract has the unilateral, enforceable right to terminate a wholly unperformed contract without compensating the other party. A contract would be considered wholly unperformed if the entity has not yet transferred any of the promised goods or services to the customer, and the entity has not received any consideration or entitlement to consideration. In this situation, there is clearly no revenue to recognize as there has not been any exchange under the contract.

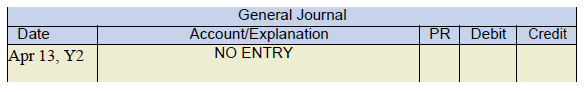

Remember – when entering into a contract, usually there is no journal entry required because neither party has performed on the contract. A journal entry is created when delivery of the goods or services has happened.

As an example:

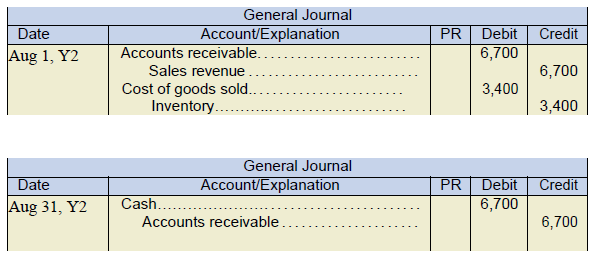

On April 13, Y2, Company A enters into a contract to sell a good to Company X on August 1, Y2. Company X will pay the full contract price of $6,700 on August 31, Y2. The cost of the goods sold is $3,400 and delivery of the goods happen on August 1, Y2.

What are the journal entries Company A should record?

There is no entry on April 13, Y2 because neither party has performed on the contract, the parties have agreed to do something in the future.

There is no entry on April 13, Y2 because neither party has performed on the contract, the parties have agreed to do something in the future.

To recap, when identifying the contract be aware of when a journal entry should be recorded. When a contract is agreed to is not the time to make a journal entry. Only when the good or service has been provided, for accounting purposes, a journal entry should be made.

5.2.2. Identify the Performance Obligations

A performance obligation is a promise in a contract to provide a product or service to a customer. The promise may be implied or explicit. Performance obligation is a critical step, as the performance obligations will determine when revenue is recognized. The standard requires that the promised performance obligation be identified either as distinct goods and services or as a series of distinct goods and services that are substantially the same and that have the same pattern of transfer to the customer. A performance obligation exists only if there is a transfer of goods or services to a customer. This limitation in the definition means that internal administrative tasks required to manage a contract are not, in themselves, performance obligations.

During the development and implementation of IFRS 15, there was a great deal of discussion around the concept of distinct goods or services. The definition of “distinct” in this context contains two criteria: the customer can benefit from the good or service either on its own or together with other resources that are already available to the customer, and the contract contains a separately identifiable promise to transfer the good or service. It is important to note that both of these criteria must be satisfied to meet the definition of “distinct.” For some contracts, the satisfaction of the second criteria may require some analysis. The standard provides further clarification by specifying the following indicators of a combined good or service (i.e., a single performance obligation):

- Significant services in integrating the goods or services with other goods or services are provided in the contract.

- The goods or services provided significantly modify or customize other goods or services provided in the contract.

- The goods or services are highly interdependent.

The standard provides further detailed examples to illustrate these concepts. A common, simple example can also illustrate the idea of “distinct”. Consider a customer who wishes to build a brick wall. There are two ways this could be done. The customer could arrange with a local building supply warehouse to deliver all the required materials (bricks, mortar, tools, etc.) The company could then arrange a separate contract with a local mason to build the wall. In this case, there are two separate contracts. In the first contract, the performance obligation is satisfied when the materials are delivered to the building site. The performance obligation in the second contract will be satisfied when the mason completes construction of the wall.

Now consider a different scenario: the company hires a local contractor to build the wall. The contractor purchases all the materials and arranges to have them delivered to the building site. Although these materials could meet the first criteria (i.e., the customer could benefit from them), the second criteria is not met. The contractor has made a promise for a single good: the completed wall. The contractor is going to provide significant services in integrating the goods (assembling the bricks with the mortar), the service modifies the goods, and the goods and services are interdependent (the skilled labour of the contractor is required to assemble the raw materials). In this case, the delivery of the materials to the building site does not satisfy a performance obligation. The performance obligation is not satisfied until the wall is completed.

To provide further clarity on the nature of performance obligations, the standard provides the following examples of goods and services:

- Sale of goods produced by the entity

- Resale of goods purchased by the entity

- Resale of rights to goods or services purchased by the entity

- Performing a contractually agreed upon task

- Providing a service of standing ready to provide goods or services

- Providing a service of arranging for another party the transfer of goods or services

- Granting rights to goods or services to be provided in the future that the customer can resell

- Constructing, manufacturing, or developing an asset on behalf of a customer

- Granting licenses

- Granting options to purchase additional goods or services

(CPA Handbook – Accounting, IFRS 15.26)

In some of the examples above, it is apparent that the entity would be acting as an agent for the benefit of a principal. In determining whether an agency relationship exists, the key factor to consider is control. If the entity controls the good or service before it is transferred to the customer, then the entity is a principal. If the entity does not control the good or service, the entity would be considered an agent. The main concern from an accounting perspective in these situations is the amount of revenue to recognize. For a principal, the gross amount of consideration expected from the transaction is considered revenue. For an agent, only the fee or commission earned from the transfer of goods or services is reported as revenue.

An example of accounting for identifying performance obligations could include selling a product that has a warranty involved. Accounting for warranties will be discussed in more detail in Intermediate Accounting 2. When warranties are attached to a product, a company should not only record the sale of the product but any unearned revenue related to the sale of the warranty.

Let’s consider an example:

MVR Motors sells an automobile to LMM Auto Dealers. The price includes seven months of warranty services. The warranty can be sold on a stand-alone basis by MVR for a fee. After the seven-month period, a customer can renew the services for a fee.

Question – are the automobile and the warranty services distinct within the contract?

Answer – Yes. In this contract, two performance obligations exist. One obligation relates to the automobile and the second obligation relates to the warranty services. There are two distinct and non-related services because the customer can benefit from the use of both the automobile and the warranty services.

If there are multiple services provided, the revenue related to each service should be recorded separately. Warranties often accompany a good that is sold. A service-type warranty represents a separate service and are considered to be an additional performance obligation. As a result, companies should allocate a portion of the sales price to the warranty performance obligation. The company should recognize revenue in the period tat the service-type warranty is in effect. An assurance-type warranty is a quality guarantee that the good or service is free from defects at point of sale. With an assurance-type warranty, the warranty obligation should be expensed in the period when the goods are provided or the service is performed. In addition, the company should record a liability for reporting estimated future, potential, payments. In some cases customers have the option to purchase extended warranties.

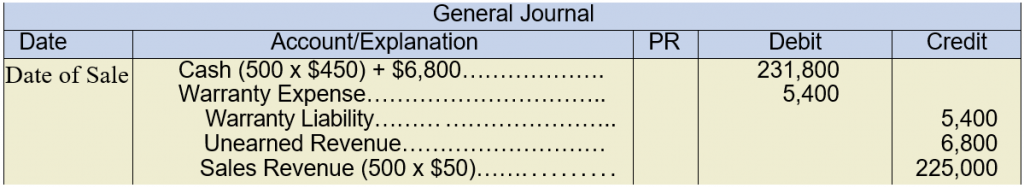

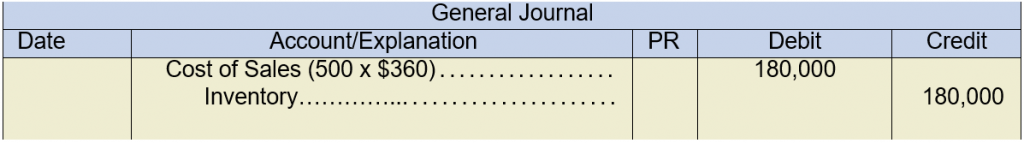

Let’s consider an example:

Assume that Aylmer Inc. sold 500 computers for $450 each. Each computer has a warranty that it is free from any defects. The cost of each computer is $360. The assurance-type warranty is two years with an estimated cost of $5,400. In addition, Aylmer sold extended warranties on 200 computers for three years beyond the two-year period for $6,800.

Question – what journal entry should be prepared?

Answer – we need to be sure that the revenues and liabilities (asset-liability approach) are properly stated with the following journal entry:

5.2.3. Determine the Transaction Price

The standard defines the transaction price as the amount of the consideration the entity expects to be entitled in exchange for transferring promised goods or services, excluding amounts collected on behalf of third parties. This consideration may be fixed or variable in nature. As well, there may be an implied financing component present in the consideration. Also, there are certain contracts that may require the payment of non-cash consideration. The transaction price is the amount of consideration that a company expects to receive from a customer in exchange for a good or service.

Variable consideration can occur when discounts, rebates, refunds, credits, price concessions, or other incentives or penalties exist. When variable consideration is present in a contract, the amount should be estimated using either the expected value (the sum of probability-weighted amounts from a range of possible amounts) or the most likely amount (usually more appropriate when the range contains only a few choices). Variable consideration can be included in the transaction price only if it is highly probable that a significant reversal in the amount cumulative revenue recognized will not occur in the future. The standard does not define what is meant by “highly probable”, but it does provide a list of factors to consider when making this assessment. These situations require professional judgment and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative factors.

Time-value of money or non-cash consideration are two important aspects of determining the transaction price. Time value of money should be considered if the contract involves a significant financing component. When a sales transaction involves consideration to be paid over time (financing), the amount of revenue is determined by discounting (present value) the payments. A note receivable is set up for the present value/discounted amount of cash flow. The offset is to sales revenue. As payments are received from the customer, interest revenue is earned.

In the situation of a non-cash consideration transaction. Companies generally recognize revenue on the basis of the fair value of what is received. Another word for a non-cash transaction is barter.

In some contracts, the entity may be providing significant financing services, even if these are not explicitly stated in the contract. A simple example would be goods sold which require payment in two years’ time. Although the contract may not state an interest rate, there is clearly a financing component present. The selling entity needs to account for the time value of money in determining the portion of the sale that relates to the goods and the portion that relates to the financing provided. In determining if a significant financing component exists, the entity should consider the difference between the consideration and the cash selling price of the goods or services, the length of time between the transfer of control and the customer’s payment, and prevailing interest rates in the relevant market.

The discount rate used should reflect the rate that would be arrived at if the entity and the customer had engaged in a separate financing contract. This rate should reflect current market conditions, as well as the customer’s credit rating, collateral offered, and any other relevant factors. As a practical expedient, the standard allows entities to ignore the financing component if the time from delivery of goods or services to receipt of payment is expected to be one year or less.

When a contract allows non-cash consideration to be paid by a customer, that consideration should be measured at its fair value. In some cases, it may not be possible to determine the fair value of the consideration received. In these cases, the entity should use the stand-alone selling prices of the promised goods or services to determine the transaction price.

5.2.4. Allocate the Transaction Price to the Performance Obligations

Where multiple performance obligations are included in a single-price contract, the price should be allocated based on the relative proportions of the stand-alone selling prices of each component at the contract inception date. Where the stand-alone selling prices cannot be determined, other suitable estimation methods include:

- the adjusted market assessment approach,

- the expected cost plus a margin approach, and

- the residual approach (permissible only in limited circumstances).

The application of these approaches may result in the identification of performance obligations that hadn’t previously been identified due to the lack of stand-alone prices. If the customer receives a discount from purchasing a bundle of goods or services, this discount would normally be allocated in a proportional manner to the different performance obligations. The standard does, however, allow for discounts to be allocated in a disproportional manner if certain criteria are met. When variable consideration is present in a contract, the standard allows the variable component to be allocated to specific performance obligations if certain criteria are met. Otherwise, the variable consideration would be allocated in a proportional manner, similar to other consideration.

5.2.5. Recognize Revenue When (or as) the Entity Satisfies a Performance Obligation

Revenue should be recognized when the performance obligation has been satisfied. This occurs when the entity has transferred control of an asset to the customer. In this context, an asset includes either goods or services. A service is considered an asset because the customer obtains a benefit from its use, even if only briefly. The performance obligations can be satisfied either at a point in time or over time.

The standard defines control as the ability to direct the use of, and obtain substantially all of the benefits from the asset. (CPA Canada Handbook – Accounting, IFRS 15.33). Benefits are described as future cash flows, and can take the form of either inflows or reductions of outflows. Thus, cash flows can include not only the revenue derived directly from selling the asset, but also savings from using the asset to enhance other assets, or even the settlement of liabilities with the asset.

Many common business transactions result in performance obligations being satisfied at a point in time. This point could also be described as the critical event. For example, when you buy groceries at your local convenience store, the critical event occurs when you exchange cash for possession of the goods. Once you leave the store with the groceries, revenue has been earned by the store. The proprietor no longer has any responsibility for or control over the goods. Other factors that can be considered when determining if control of an asset has been transferred include the transfer of legal title, the transfer of physical possession, the acceptance by the customer of the asset, the entity’s entitlement to payment by the customer, and the transfer of significant risks and rewards of ownership. In the example of groceries purchased, the reward is the realization of the cash received from the sale. Prior to the sale, the risk to the vendor is that the food products may pass their sell-by date or may not be saleable due to changes in consumer tastes. Once you have purchased the goods, you are accepting responsibility for consuming the product prior to the sell-by date. Thus, the rewards have been transferred to the seller and the risks have been transferred to the buyer.

Often, the question of control can be answered by looking at a number of the factors identified above. As long as a company possesses the goods and still holds the title to the goods, there is both a risk (i.e., goods could be damaged, stolen, or destroyed) and a reward (i.e., goods can pledged or sold) available to the vendor. Sometimes, a vendor may transfer legal title to the customer but still maintain physical possession of the goods. In late 2000, Nortel Networks Corporation recorded approximately $1 billion of revenue using bill-and-hold transactions. These transactions were recorded as sales, but the company maintained possession of the goods until some later date when the customer requested delivery. In order to promote these types of sales, the company offered several different incentives to its customers. To report these types of transactions, US GAAP required that several conditions be met, including the conditions that the transaction must be requested by the customer and serve some legitimate business purpose. Nortel’s actions violated these two conditions, and as such, the company was later required to restate revenues for the fourth quarter by over $1 billion.

The selling of services can create further accounting problems, as there is no longer the obvious transfer of a physical product to indicate completion of the earnings process. When you get a haircut, the service will be completed when you are satisfied with the cut and the barber enters the sale into the cash register. This can still be described as revenue earned at a point in time, as the completion of the haircut can be seen to be a critical event. However, some activities can take longer to complete, and they can even extend over several accounting periods. When a company agrees to provide a service over a period of time that crosses several fiscal years, the problem is to determine in which accounting periods to recognize the revenue. IFRS 15 requires one of three criteria be met to recognize revenue over time:

- The customer simultaneously receives and consumes benefits as the entity performs;

- The entity’s performance creates or enhances an asset that the customer controls; or

- The entity’s performance does not create an asset with an alternative use to the entity and entity has an enforceable right to payment.

(CPA Canada Handbook – Accounting, IFRS 15.35)

When recognizing revenue for a performance obligation that is satisfied over time, it is essential that the entity have a reliable method for measuring progress. These methods should be based on either inputs or outputs. If the entity cannot reasonably measure its progress towards satisfaction of the performance obligation, then revenue should not be recognized. In some cases, although reliable measures of progress are not available, there is still a reasonable expectation that costs incurred will be recovered. In this in- stance, revenue would be recognized equal to the costs incurred. This is referred to as the zero-margin method. Revenue recognition for long term contracts will be discussed further in Section 5.3.6.

Accounting for revenue over time can create further problems when both goods and services are delivered. For example, in 2006, Nortel Networks was required to restate its financial statements due to improper accounting of several “multiple element arrangements.” Nortel was engaged in many different types of long-term contracts with customers where installation, network planning, engineering, hardware, software, upgrades, and customer-support features were all included in the contract price. The accounting for these contracts was complicated, and the restatement was required because certain undelivered products and services were not considered separate accounting units, as no fair value could be determined for them.

5.2.6. Contract Costs

IFRS 15 also provides guidance on how to account for costs incurred to obtain and fulfill a contract. When obtaining a contract, any incremental costs incurred should be capitalized as an asset and amortized over the life of the contract. These costs only include those direct costs that would not have been incurred if the contract had not been obtained. A common example would be commissions paid to sales staff. As a practical expedient, the standard allows the costs to be expensed immediately for contracts terms of one year or less. This particular section of the standard has generated some debate, particularly in the telecommunications sector. Common practice in this industry usually involves expensing employee commissions at the time the contract is signed. Some industry representatives have expressed concern that the requirement to capitalize contract costs, along with other aspects of the standard, will result in significant changes and investments in IT systems to properly track the information.

For costs incurred to fulfill a contract, the standard requires capitalization only if the costs relate directly to the contract, the costs generate or enhance resources that will be used to satisfy the performance obligations, and the costs are expected to be recovered. These conditions will generally prevent the capitalization of general and administrative costs that are not explicitly chargeable under a contract or the cost of wasted resources that are not reflected in the price of the contract. However, overhead costs such as project management, supervision, insurance, and depreciation may be eligible for capitalization if they relate directly to the contract.