2.4 The Conceptual Framework

According the CPA Canada Handbook, “the purpose of the Conceptual Framework is to:

- assist the International Accounting Standards Board to develop IFRS Standards that are based on consistent concepts;

- assist preparers to develop consistent accounting policies when no Standard applies to a particular transaction or other event, or when a Standard allows a choice of accounting policy; and

- assist all parties to understand and interpret the Standards.” (CPA Canada, 2019).

A solid, coherent framework of principles is important not only to standard setters who need to develop new principles in response to changes in the business environment but also to practicing accountants who may encounter unusual or unique types of business transactions on a daily basis.

The IASB and the FASB had been working on a joint conceptual framework for several years, but this project was replaced by an IASB-only project, which was completed in 2018. This framework is currently used in Canada for publicly accountable enterprises. The conceptual framework used for private enterprises is very similar in content, although the structure, terminology, and emphasis differ slightly. We will focus on the IASB framework, which is located in Part 1 of the CPA Canada Handbook.

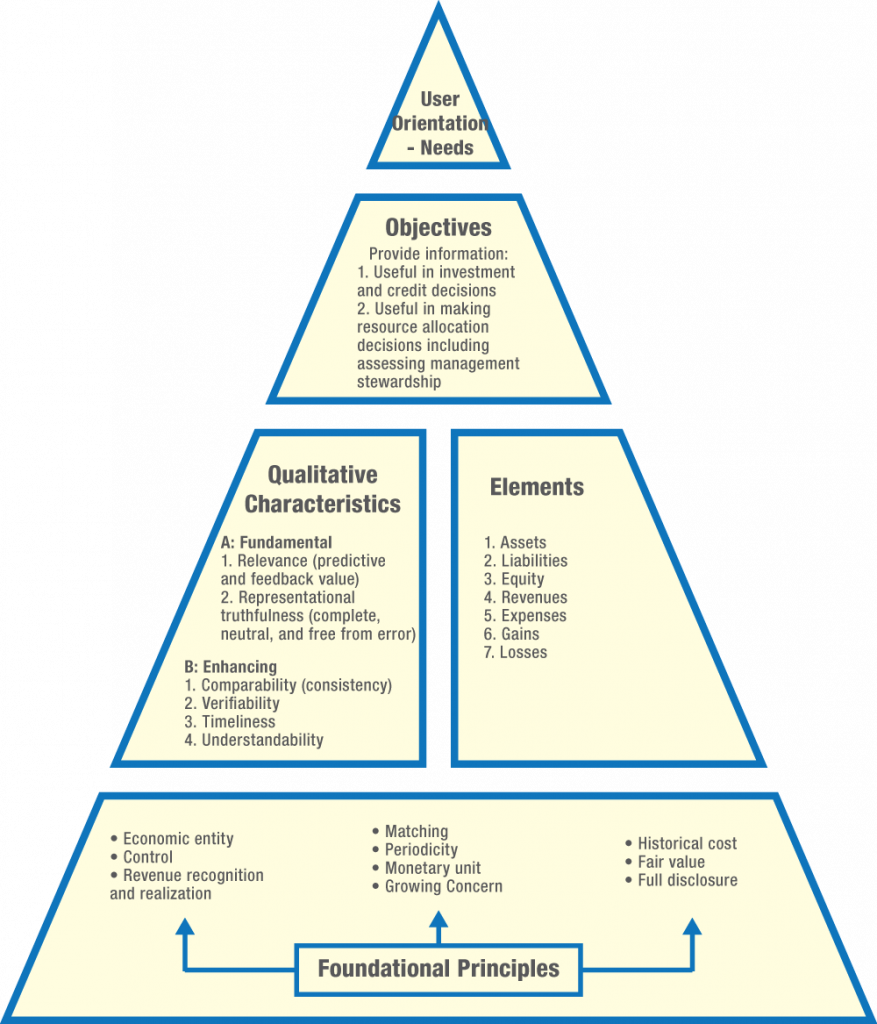

2.4.1 The Objective of Financial Reporting

The conceptual framework opens with a statement of the purpose of financial reporting, which was discussed previously in this chapter. Recall that the key components of this definition are that financial information must be useful for making decisions, primarily about investment or lending of resources to a business entity, or evaluation of management stewardship. The conceptual framework then proceeds to discuss the qualitative characteristics of useful accounting information.

2.4.2 Qualitative Characteristics of Useful Information

The conceptual framework identifies fundamental and enhancing qualitative characteristics of useful information.

The fundamental characteristics are

- relevance and

- faithful representation.

The enhancing characteristics are

- comparability,

- verifiability,

- timeliness, and

- understandability.

The basic conceptual framework:

The essential characteristics of accounting are:

- Identification, measurement and communication of financial information.

The expanded conceptual framework for financial reporting:

Fundamental Characteristics

Relevance means that information is “capable of making a difference in the decisions made by users” (CPA Canada, 2019, QC2.6). The definition is further refined to state that information is capable of influencing decisions if it has predictive value, confirmatory value, or both. Predictive value means that the information can be used to assist in the process of making predictions about future events, such as potential investment returns, credit defaults, and other decisions that financial-statement users need to make. Note that although the information may assist in these decisions, the information is not in itself a prediction or forecast.

Rather, the information is the raw material used by the decision maker to make the prediction. Confirmatory value means that the information provides some feedback about previous decisions that were made. Quite often, the same information may be useful for prediction and feedback purposes, but in different time periods.

An income statement may help an investor decide to invest in a company this year, and next year’s income statement, when released, will provide feedback as to whether the investment decision was correct. The framework also mentions the concept of materiality. A piece of information is considered material if its omission would affect a user’s decision. Materiality is a concept used frequently by both internal accountants and auditors in determining the need to make adjustments for errors identified. Clearly, an item that is not deemed to be material is not relevant, as it would not affect a user’s decision.

Faithful representation means that the financial information presented represents the true economic substance or state of the item being reported. This does not mean, however, that the representation must be 100 percent accurate, as perfection is rarely attainable. The CPA Handbook indicates that for information to faithfully represent an economic phenomenon, it must be complete, neutral, and free from error.

Information is complete if there is sufficient disclosure for the reader to understand the underlying phenomenon or event. This means that many financial disclosures will require additional explanations that go beyond a mere reporting of the quantitative values. Completeness is the motivation behind many of the note disclosures contained in financial statements. Because financial-statement users are trying to make predictions about future events, more detail is often needed than simply the balance sheet or income- statement amount. For example, if an investor wanted to understand a manufacturing company’s requirements for future replacement of property, plant, and equipment assets, detailed information about the remaining useful lives of the assets and related depreciation periods and methods would be needed. Similarly, if a creditor wanted to assess the possible future effect on cash flows of a lease agreement, detailed information about the term of the lease, the required payments, and possible renewal options would be needed.

The neutrality concept suggests that the information is not biased and does not favour one particular outcome or prediction over another. This can often be difficult to assess, as many judgments are required in some accounting measures. There are many motivations for managers and preparers of financial statements to bias or influence the reporting of certain results. These motivations will be discussed later in this chapter. The professional accountant’s role is to ensure that these biases are understood and controlled so that the reported financial results are not misleading to readers. Neutrality can also be supported by the use of prudent judgment. “Prudence is the exercise of caution when making judgments under conditions of uncertainty” (CPA Canada, 2019, QC2.16). Prudence has historically been described as a cautious attitude that does not allow for the overstatement of assets or income, or an understatement of liabilities or expenses. However, the definition in the Conceptual Framework equally suggests that assets or income should not be understated and that liabilities or expenses should not be overstated. The Framework makes this explicit statement to suggest that asymmetry in standards is not necessary.

However, there are examples of specific standards in IFRS that do have unbalanced requirements (i.e. have a requirement for more persuasive evidence when recognizing an income compared to an expense). These types of unbalanced standards are considered acceptable if they result in more relevant and faithfully representative information. The application of prudence obviously takes a high degree of skill and professional judgment. Prudence is not considered a qualitative characteristic on its own, but it is sound advice to the practicing accountant.

As noted previously, information that is free from errors is not a guarantee of certainty or 100 percent accuracy. Rather, this criterion suggests that the economic phenomenon is accurately described and the process at arriving at the reported amount has properly applied. There is still the possibility that a reported amount could be incorrect. For example, at the end of the fiscal year, many companies will make an allowance for doubtful accounts to reflect the possibility that some accounts receivable will not be collected. At the balance sheet date, there is no way to be 100 percent certain that the reported allowance is correct. Only the passage of time will reveal the truth about this estimate. However, we can still say that the allowance is free from error if we can determine that a logical and consistent process has been applied to determine the amount and that this process is adequately described in the financial statements. This way, readers are able to make their own assessments of the risks involved in collecting these future cash flows.

It should be noted that the presence of both of the fundamental characteristics is required for information to be useful. An error-free representation of an irrelevant phenomenon is not much use to financial-statement readers. Similarly, if a relevant measure cannot be described with any degree of accuracy, then users will not find this information very useful for predicting future cash flows.

Enhancing Characteristics

The conceptual framework describes four additional qualitative characteristics that should enhance the usefulness of information that is already determined to be relevant and faithfully represented. These characteristics are comparability, verifiability, timeliness, and understandability.

Comparability is the quality that allows readers to compare either results from one entity with another entity or results from the same entity from one year with another year. This quality is important because readers such as investors are interested in making decisions whether to purchase one company’s shares over another’s or to simply divest a share already held. One key component of the comparability quality is consistency. Consistency refers to the use of the same method to account for the same items, either within the same entity from one period to the next or across different entities for the same accounting period. Consistency in application of accounting principles can lead to comparability, but comparability is a broader concept than consistency. Also, comparability must not be confused with uniformity. Items that are fundamentally different in nature should be accounted for differently.

The verifiability quality suggests that two or more independent and knowledgeable ob- servers could come to the same conclusion about the reported amount of a particular financial-statement item. This does not mean that the observers have to be in complete agreement with each other. In the case of an estimated amount on the financial statements, such as an allowance for doubtful accounts, it is possible that two auditors may agree that the amount should fall within a certain range, but each may have different opinion of which end of the range is more probable. If they agree on the range, however, we can still say the amount is verifiable. Verification may be performed by either directly observing the item, such as examining a purchase invoice issued by a vendor, or indirectly verifying the inputs and calculations of a model to determine the output, such as reviewing the assumptions and recalculating the amount of an allowance for doubtful accounts by using data from an aged trial balance of accounts receivable.

Timeliness is one of the simplest but most important concepts in accounting. Generally, information needs to be current to be useful. Investors and other users need to know the economic condition of the business at the present moment, not at some previous period. However, past information can still be useful for tracking trends and may be especially useful for evaluating management stewardship.

Understandability is the one characteristic that the accounting profession has often been accused of disregarding. It is generally assumed that readers of financial statements should have a reasonable understanding of business issues and basic accounting terminology. However, many business transactions are inherently complex, and the accountant faces a challenge in crafting the disclosures in such a way that they completely and concisely describe the economic nature of the item while still being comprehensible. Financial disclosures should be reviewed by non-specialist, knowledgeable readers to ensure the accountant has achieved the quality of understandability.

As mentioned previously, accountants are often faced with trade-offs in preparing financial disclosures. This is especially true when considering the application of the various qualitative characteristics. Sometimes, the need for timeliness may result less-than-optimal verifiability, as verification of some items may require the passage of time. As a result, the accountant is forced to make estimations in order to ensure the information is available within a reasonable time. As well, all information has a cost, and companies will carefully consider the cost of producing the information compared with the benefits that can be obtained from the information, such as improving relevance or faithful representation. These challenges point to the conclusion that accounting is an imperfect measurement system that requires judgment in both the preparation and interpretation of the information.

2.4.3 Elements of Financial Statements

The CPA Canada Handbook includes a section describing a number of essential financial- statement elements. This section is not intended to be an exhaustive list of each item that could appear on the financial statements. Rather, it describes broad categories of financial-statement elements and defines them using key concepts that identify the essential elements of each category. These broadly based definitions will require the accountant to use judgment in the determination of the nature and the specific treatment and disclosure of business transactions. However, the accountant’s judgment can also help ensure that financial statements properly reflect the underlying economic nature of the transaction, not just the legal form that may have been designed to circumvent more specific rules.

An Underlying Assumption

Before commencing a detailed examination of elements of financial statements, it is important to understand the key assumption underlying the reporting process. It is normally assumed that companies are operating as a going concern. This means that the company is expected to continue operating into the foreseeable future and that there will be no need to liquidate significant portions of the business or otherwise materially scale back operations. This assumption is important, because a company that is not a going concern would likely need to apply a different method of accounting in order not to be misleading. If a company needed to liquidate equipment at a substantial discount due to bankruptcy or other financial distress, it would not be appropriate to carry those assets at depreciated cost. In situations of financial distress, the accountant needs to carefully consider the going-concern assumption in determining the correct accounting treatment.

Assets

An asset is the first financial-statement element that needs to be considered. In the simplest sense, an asset is something that a business owns. The CPA Canada Handbook defines an asset as “a present economic resource controlled by the entity as a result of past events” (CPA Canada, 2019, 4.3). The definition further states that an economic resource is a right that can produce economic benefits. The key point in this definition is that economic benefits are expected to be received at some point in the future as a result of holding the resource. The most obvious benefit is the future inflow of cash. This can be seen very clearly with an item such as inventory held by a retail store, as the store expects to sell the items in a short period of time to generate cash. However, an asset could also be a piece of equipment installed in a factory that reduces the consumption of electricity by production processes. Although this equipment will not directly generate a future cash inflow, it does reduce a future cash outflow. This is also considered an economic benefit. The use of the term “right” in the definition also suggests other types of relationships, such as the right to use a patented process or the right to receive a favourable amount under a derivative contract. Rights are often established by a legal contract or enacted legislation, but there are other ways that rights can be considered assets, even without legal form. It is also important to note that the right must be capable of producing benefits beyond those available to other parties. An artistic work that is legally available in the public domain cannot be considered an asset to an entity, since other parties can also equally access the work.

Many assets have a tangible, or physical, form. However, some assets, such as accounts receivable or a patent, have no physical form. In the case of an account receivable from a customer, the future benefit results from the legal right the company holds to enforce payment. For a patent, the future benefit results from the company’s ability to sell its product while maintaining some protection from competitors. Cash in a bank account does not have physical form, but it can be used as a medium of exchange.

It should also be noted that, although we can generally think of assets as something we own, the actual legal title to the resource does not necessarily need to belong to the company for it to be considered an asset. A contract, such as a long-term lease that conveys benefits to the leasing party over a significant portion of the asset’s useful life may be considered an asset in certain circumstances.

Liabilities

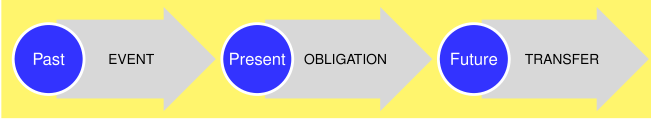

A liability is defined as “a present obligation of the entity to transfer an economic resource as a result of past events” (CPA Canada, 2019, 4.26). This definition can be visualized through a time-continuum graphic:

When we prepare a balance sheet, it represents the present moment, so the obligation gets reported as a liability. This obligation is often a legal obligation, as in the case when goods are purchased on account, resulting in an accounts payable entry, or when money is borrowed from a bank, resulting in a loan payable. As well, this legal obligation can exist even in the absence of a formal contract. A company still has to report wages payable for any work performed by an employee but not yet paid, even if that work was performed under the terms of an informal, casual labour agreement.

Liabilities can also result from common business practice or custom, even if there is no legally enforceable amount. If a retailer of mobile telephones agrees to replace one broken screen per customer, then the expected cost of these replacements should be reported as a liability, even if the damage resulted from the customer’s neglect and there is no legal obligation to pay. This type of liability is referred to as a constructive obligation. As well, companies may record liabilities based on equitable principles. If a company significantly reduces its workforce, it may feel a moral obligation to provide career transition counselling to its laid-off employees, even though there is no legal obligation to do so. In general, an obligation is considered a duty or responsibility that an entity has no practical ability to avoid.

The settlement of the liability usually involves the future transfer of cash, but it can also be settled by transferring other assets. As well, liabilities are sometimes settled through the provision of services in the future. A health club that requires its members to pay for one year’s fees in advance has an obligation to make the facilities available to its members for that time. Less common ways to settle liabilities include replacing the liability with a new liability and converting the liability into equity of the business. It should be noted that the determination of the value of the liability to be recorded sometimes requires significant judgment. An example of this would be the obligation under a pension plan to make future payments to retirees. We will discuss this estimation problem in more detail in later chapters dealing with liabilities.

Equity

Equity is the owners’ residual interest in the business, representing the remaining amount of assets available after all liabilities have been settled. Although equity can be thought of as a balancing figure, it is usually subdivided into various categories when presented on the balance sheet. Many of these classifications are related to legal requirements regarding the ownership interest. The usual categories of equity include share capital, which can include common and preferred shares, retained earnings, and accumulated other comprehensive income (IFRS only). However, other types of equity can arise on certain types of transactions, such as contributed surplus, appropriated retained earnings, and other reserves that may be allowed under local law. The purpose of all these subcategories of equity is to give readers enough information to understand how and when the owners may be able to receive a distribution of their interests. For example, restrictions on retained earnings or levels of preferences on shares issued may constrain the future payment of dividends to common shareholders. A potential investor would want to know this before investing in the company.

It should also be noted that the company’s reported equity does not represent its value, either in a real sense or in the market. The prices that shares trade at in the stock market represent the cumulative decisions of investors, based on all information that is available. Although financial statements form part of this total pool of information, there are so many other factors used by investors to value a company that it is unlikely that the market value of a company would equal the reported amount of equity on the balance sheet.

Income

Income is defined as “increases in assets, or decreases in liabilities, that result in in- creases in equity, other than those relating to contributions from holders of equity claims.” (CPA Canada, 2019, 4.68). Notice that the definition is based on presence of changes in assets or liabilities, rather than on the concept of something being earned. This represents the balance sheet approach used in the conceptual framework, which considers any measure of performance, such as profit, to simply be a representation of the change in balance sheet amounts. This perspective is quite different from some historical views adopted previously in various jurisdictions, which viewed the primary purpose of accounting to be the measurement of profit (an income-statement approach).

Income can include both revenues and gains. Revenues arise in the course of the normal activities of the business; gains arise from either the disposal of noncurrent assets (realized gains) or the revaluation of noncurrent assets (unrealized gains). Unrealized gains on certain types of assets are usually included in other comprehensive income, a concept that will be discussed in later chapters.

Expenses

Expenses are defined as “decreases in assets, or increases in liabilities, that result in decreases in equity, other than those relating to distributions to holders of equity claims.” (CPA Canada, 2019, 4.69). Note that this definition is really just the inverse of the definition of income. Similarly, expenses can include those that are incurred in the regular operation of the business and those that result from losses. Again, losses can be either realized or unrealized, and the definition is the same it was for gains.

To summarize:

| IFRS | ASPE |

|---|---|

| Statement of financial performance

OR Statement of profit and loss and Statement of other comprehensive income* |

Income Statement

OCI does not exist |

| Statement of financial position | Balance sheet |

| Statement of changes in shareholders’ equity | Statement of retained earnings |

| Statement of cash flows | Cash flow statement |

| Element | ASPE | IFRS |

|---|---|---|

| Revenues/Income | Increases in economic resources, which result from ordinary operations. | Increases in assets of decreases in liabilities other than those relating to contributions from shareholders. |

| Expenses | Decreases in economic resources that result from ordinary revenue-generating activities. | No distinction between ordinary revenue-generating activities and losses. |

| Gains/Losses | Increases/Decreases in equity from an entity’s peripheral or incidental transactions except revenues/expenses and owner’s activity | Revenues and gains are grouped together under Income, and expenses and losses are grouped together under Expenses. |

2.4.4 Recognition

Items are recognized in financial statements when they meet the definition of a financial statement element. (CPA Canada, 2019, 5.6). However, the Conceptual Framework acknowledges that there may be circumstances when an item that meets the definition of an element is still not recognized, because doing so would not provide useful information. In referencing usefulness, the Framework is acknowledging the fundamental qualitative characteristics of relevance and faithful representation. If it is uncertain whether an asset or liability exists, or if the probability of an inflow or outflow of economic benefits is low, it is possible that recognition is not warranted, since the relevance of the information is questionable. Similarly, if the measurement uncertainty present in estimated amounts were too great, the element would not be faithfully represented, and accordingly, should not be recognized. It is also possible that if the costs of recognition outweigh the benefits to users of the financial statements, the item will not be recognized.

Recognition means the item is included directly in one of the financial statements and not simply disclosed in the notes. However, if an item does not meet the criteria for recognition, it may still be necessary to disclose details in the notes to the financial statements. A pending lawsuit judgment at the reporting date may not meet the criterion of measurement certainty, but the possible future impact of the event could still be of interest to readers.

2.4.5 Measurement Base

The Conceptual Framework also notes that once recognition is affirmed, the appropriate measurement base needs to be considered. The following measurement bases are identified in the conceptual framework:

- Historical cost

- Current value, which includes

- Fair value

- Value in use/fulfillment value, and

- Current cost

Historical cost is perhaps the most well-entrenched concept in accounting. This simply means that items are recorded at the actual amount of cash paid or received at the time of the original transaction. This concept has persisted in accounting thought for so long because of its relative reliability and verifiability.

However, the concept is often criticized because historical cost information tends to lose relevance as time passes. This can be particularly true for long-lived assets, such as real estate.

The current value concept results in elements being reported at amounts that reflect current conditions at the measurement date. This measurement base tries to achieve greater relevance by using current information, but it may not always be possible to represent this information faithfully when active markets for the item do not exist. It may be very difficult to find the current cost of a unique or specialized asset that was purpose built for a company.

Fair value is the price that would be received to sell an asset, or paid to transfer a liability, in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date (CPA Canada, 2019, 6.12). This amount can be easily determined when active markets exist. However, if there is no active market for the item in question, the fair value may still be estimated using a discounted cash flow technique. Obviously, the more assumptions required in deriving the fair value, the more measurement uncertainty will exist.

Value in use is also a discounted cash flow technique. It differs from fair value in that it uses entity specific assumptions, rather than market assumptions. In other words, the entity projects future cash flows based on the specific way it uses the asset in question, rather than cash flows based on market assumptions about the use of the asset. In many cases, fair value and value in use may result in the same valuation, but this is not necessarily true in all cases.

Current cost is the cost to acquire an equivalent asset at the measurement date. This cost will include any transaction costs to acquire the asset, and will take into consideration the age and condition of the asset, along with other factors. Current cost represents an entry value, while fair value and value in use represent exit values.

All of the measurement bases identified have both strengths and weaknesses in terms of their overall decision usefulness for readers. Thus, there are always trade-offs and compromises evident when accounting standards are set. It is not surprising, then, to see that current accounting standards are a hybrid, or conglomeration, of these different bases. Historical cost is still the most common base used, but many accounting standards for specific items will allow or require other bases as well.

It should be noted that the Conceptual Framework’s discussion of measurement bases should be read in conjunction with IFRS 13 – Fair Value Measurement. While the Conceptual Framework provides a broad overview of possible measurement bases, IFRS 13 provides more specific guidance on how to determine fair value. Fair value is a concept that is applied to a number of different accounting transactions under IFRS. IFRS 13 suggests that valuation techniques should maximize the use of observable inputs and minimize the use of unobservable inputs. The standard further applies a hierarchy to those inputs to assist the accountant in assessing the quality of the data used for valuation. Level 1 of the hierarchy represents unadjusted, quoted prices in active markets for identical assets or liabilities.

Level 2 inputs are those that are directly or indirectly observable but do not meet the definition of Level 1. This could include quoted prices from inactive markets or quoted prices for similar (but not identical) assets. Level 3 inputs are those that are unobservable. In this case, valuation techniques that require the use of assumptions and calculations of future cash flows may be required. IFRS 13 recommends that Level 1 inputs should always be used where possible. Unfortunately, Level 1 inputs are often unavailable for many assets. The application of fair-value accounting as described in IFRS 13 will be discussed in more detail in subsequent chapters.

2.4.6 Capital Maintenance

The last section of the conceptual framework deals with the concept of capital maintenance. This is a broader economic concept that attempts to define the level of capital or operating capability that investors would want to maintain in a business. This is important for investors because they ultimately want to earn a return on their invested capital in order to achieve growth in their overall wealth. However, measuring this growth will depend on how capital is defined.

The conceptual framework identifies two broad approaches to this question. The measurement of the owners’ wealth can be defined in terms of financial capital or in terms of physical capital.

Financial capital maintenance is measured simply by the changes in equity reported on the company’s balance sheet. These changes can be measured either in terms of money invested or in terms of purchasing power. The monetary interpretation is consistent with the approach used in historical cost accounting, where wealth is measured in nominal units (dollars, euros, etc.). This is a simple and reasonable approach in the short term, but over longer periods, monetary values are less relevant due to inflation. A dollar in 1950 could purchase much more than it could in 2020, so comparisons of capital over longer periods become meaningless. One way to get around this problem is to apply a constant purchasing power model to capital maintenance. This attempts to apply a broad- based index, such as the Consumer Price Index, to equity in order to adjust for the effects of inflation. This should make financial results more comparable over time. However, it is very difficult to conclude that a broad-based index is representative of the actual level of inflation experienced by the company, as the company would be selling and purchasing goods that are different from those included in the index.

The concept of physical capital maintenance attempts to get around this problem by measuring productive capacity. If a company can maintain the same level of outputs year after year, then it can be said that capital is maintained, even if the nominal monetary amounts change. This approach essentially represents the rationale behind the current cost-measurement base. The difficulty in using this approach is that current cost information about each specific asset in the business would be prohibitively expensive to obtain. If, instead, the company tried to apply a general index of prices for its specific industry, it is unlikely that this index would accurately match the specific asset composition of the company.

The conceptual framework concludes that the framework will not prescribe or require a specific model because there are so many trade-offs required in determining the appropriate capital maintenance model. Rather, the framework suggests that needs of financial- statement users should be considered in determining the appropriate model.