1.3 Review – Adjusting Entries

Accrual based accounting records revenues when they are earned and expenses when they are incurred. A number of adjustments need to be made to update the value of the assets and the liabilities. The process to ensure that all accounts are reported accurately at the end of the period is called the adjusting process. This section reviews the adjusting process.

At the end of an accounting period, before financial statements can be prepared, the accounts must be reviewed for potential adjustments. This review is done by using the unadjusted trial balance. The unadjusted trial balance is a trial balance where the accounts have not yet been adjusted. The trial balance of Big Dog Carworks Corp. at January 31 was prepared earlier. It is an unadjusted trial balance because the accounts have not yet been updated for adjustments. We will use this trial balance to illustrate how adjustments are identified and recorded.

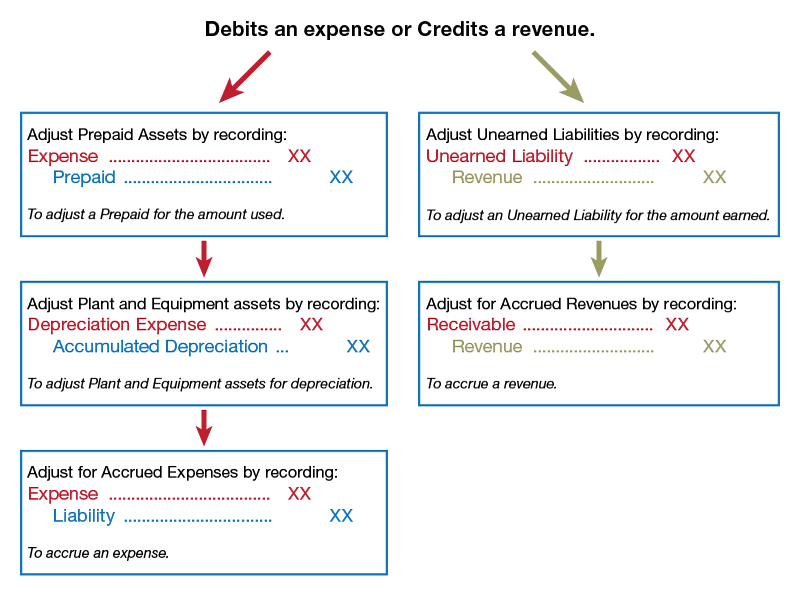

Year end (fiscal) or reporting period adjustments to the financial statements are recorded with adjusting entries. The purpose of adjusting entries is to ensure both the balance sheet and the income statement faithfully represent the account balances for the accounting period. Adjusting entries help satisfy the matching principle. There are five types of adjusting entries. Each of which will be discussed in the following sections.

Adjust

prepaid

assets

Adjust

unearned

liabilities

Adjust plant and equipment assets

Adjust for

accrued

revenues1

Adjust for

accrued

expenses2

- An accrued revenue is a revenue that has been earned but has not been collected or recorded.

- An accrued expense is an expense that has been incurred but has not yet been paid or recorded.

In summary, the adjusting entries are:

| Debit | Credit | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Deferred Expenses | XXX Expense | Prepaid XXX |

| XXX Expense | Accumulated Depreciation | ||

| Type 2 | Accrued Expenses | XXX Expense | XXX Payable |

| Type 3 | Deferred Revenues | Unearned Revenue | Revenue |

| Type 4 | Accrued Revenues | Accounts Receivable | Revenue |

To recap – adjusting entries are completed so revenues are recorded in the period in which they are earned and expenses are recorded in the period in which they are incurred, regardless of when payment occurs (matching).

Let’s review some of the adjusting entries.

Adjusting Prepaid Asset Accounts

An asset or liability account requiring adjustment at the end of an accounting period is referred to as a mixed account because it includes both a balance sheet portion and an income statement portion. The income statement portion must be removed from the asset (balance sheet) account by an adjusting entry.

Prepaid items are those items that are paid for in advance. When a cost is incurred, an asset account is debited to show the service or benefit that will be received in the future. Prepayments often occur for such items as insurance, rent, supplies and advertising. Prepaid items are considered to be an asset on the balance sheet. Prepaid items either expire (are used up) with the passage of time or by being used and consumed (normally supplies). The adjusting entries for prepaid items usually occurs when financial statements are prepared, not on a daily basis. Remember, before the adjustment is recorded, if not made, assets would be overstated and expenses would be understated.

Refer to the trial balance above which shows an unadjusted balance in prepaid insurance of $2,400. Recall from the transaction summary that Big Dog paid for a 12-month insurance policy that went into effect on January 1 (transaction 5).

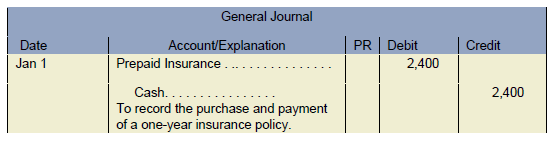

The original journal entry to record the payment of insurance would have been:

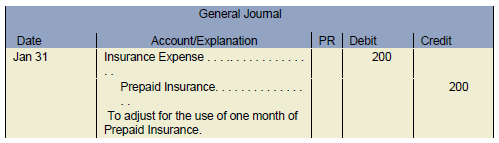

At the end of January, as one month of insurance expires, the company has to record the related expense. In summary, the company is “using up” one month of insurance. So, the adjusting entry to record the insurance expense for one month would be:

At the end of January, as one month of insurance expires, the company has to record the related expense. In summary, the company is “using up” one month of insurance. So, the adjusting entry to record the insurance expense for one month would be:

$2,400 × 1⁄12 = $200 of insurance expense that has been used up or has expired.

$2,400 × 1⁄12 = $200 of insurance expense that has been used up or has expired.

Remember, adjusting entries rarely (if ever) include cash. This above entry transfers $200 from Prepaid Insurance to Insurance Expense.

At the end of January, after the adjusting entry, Prepaid Insurance will have a balance of $2,200. The $2,200 balance represents the unexpired asset that will benefit future periods, namely, the 11 months from February to December. The $200 transferred out of prepaid insurance is posted as a debit to the Insurance Expense account to show how much insurance has been used during January.

If the adjustment was not recorded, assets on the balance sheet would be overstated by $200 and expenses would be understated by the same amount on the income statement.

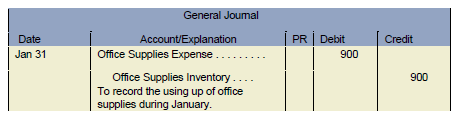

Supplies Inventory

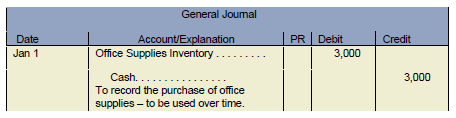

Inventories (supplies) are another type of prepaid item. Remember, when adjusting the using up (or consuming) of supplies, we are not referring to inventory that a retailer would hold for resale but we consider this type of inventory as an inventory of supplies. An example could be office supplies on hand or, an inventory of office supplies. A company may keep a large amount of office supplies on hand to be used up over a period of time. When the office supplies are initially purchased, they are debited to an inventory account: On a monthly, or annual, basis someone counts and determines the value of the office supplies on hand and an adjusting entry is prepared to record the using up (expensing, or consuming) the office supplies. Let’s assume that at the end of January, it was determined that $2,100 of office supplies remains on hand. Therefore, the company used, or has to expense $900 ($3,000 − 2,100) of office supplies.

On a monthly, or annual, basis someone counts and determines the value of the office supplies on hand and an adjusting entry is prepared to record the using up (expensing, or consuming) the office supplies. Let’s assume that at the end of January, it was determined that $2,100 of office supplies remains on hand. Therefore, the company used, or has to expense $900 ($3,000 − 2,100) of office supplies.

It’s sometimes helpful to use a “T” account, depending on the information provided. A “T” account may help with calculations to determine the amount of office supplies used.

It’s sometimes helpful to use a “T” account, depending on the information provided. A “T” account may help with calculations to determine the amount of office supplies used.

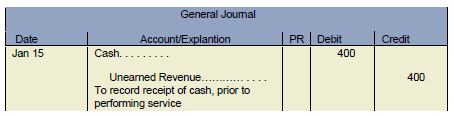

Adjusting Unearned Liability Accounts

Unearned revenue represents a liability. It represents a liability because a company may receive cash in advance of performing a service, or providing a good. Items such as rent, magazine subscriptions, and customer deposits, all received in advance are examples of unearned revenue. Unearned revenue is a liability because if the good or service is not provided, the cash received will have to be paid back (it is owed). When a payment is received from a customer for services that will be provided in a future accounting period, an unearned revenue account is credited (cash is debited) to recognize the obligation that exists. As the good or service is provided, unearned revenue becomes earned revenue.

On January 15, Big Dog received a $400 cash payment in advance of services being performed. The journal entry on January 15th would be:

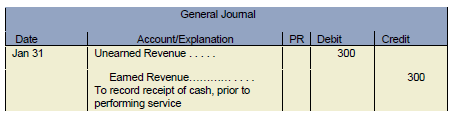

This advance payment was originally recorded as unearned, since the cash was received before services were performed. At January 31, $300 of the $400 unearned amount has been earned. Therefore, $300 must be transferred from unearned revenue into earned revenue.

This advance payment was originally recorded as unearned, since the cash was received before services were performed. At January 31, $300 of the $400 unearned amount has been earned. Therefore, $300 must be transferred from unearned revenue into earned revenue.

After posting the adjustment, the $100 remaining balance in unearned revenue ($400 − $300) represents the amount at the end of January that will be earned in the future.

After posting the adjustment, the $100 remaining balance in unearned revenue ($400 − $300) represents the amount at the end of January that will be earned in the future.

If the adjustment was not recorded, unearned revenue would be overstated (too high) by $300 causing liabilities on the balance sheet to be overstated. Additionally, revenue would be understated (too low) by $300 on the income statement if the adjustment was not recorded. Notice that the adjusting entry does not include cash.

Adjusting Plant and Equipment Asset Accounts

Plant and equipment assets, also known as long-lived assets, are expected to help generate revenues over the current and future accounting periods because they are used to produce goods, supply services, or used for administrative purposes. The truck and equipment purchased by Big Dog Carworks Corp. in January are examples of plant and equipment assets that provide economic benefits for more than one accounting period. Because plant and equipment assets are useful for more than one accounting period, their cost must be spread over the time they are used. This is done to satisfy the matching principle. For example, the $100,000 cost of a machine expected to be used over five years is not expensed entirely in the year of purchase because this would cause expenses to be overstated in Year 1 and understated in Years 2, 3, 4, and 5. Therefore, the $100,000 cost must be spread over the asset’s five-year life.

The process of allocating the cost of a plant and equipment asset over the period of time it is expected to be used is called depreciation. NOTE – we will spend more detailed time on depreciation in future chapters. The amount of depreciation is calculated using the actual cost and an estimate of the asset’s useful life and residual value. The useful life of a plant and equipment asset is an estimate of how long it will actually be used by the business regardless of how long the asset is expected to last. For example, a car might have a manufacturer’s suggested life of 10 years but a business may have a policy of depreciating cars for only 6 years. The useful life for depreciation purposes would therefore be 6 years and not 10 years. The residual value is an estimate of what the plant and equipment asset will be sold for when it is no longer used by a business. Residual value can be zero. There are different formulas for calculating depreciation. We will use the straight-line method of depreciation:

The cost less estimated residual value is the total depreciable cost of the asset. The straight-line method allocates the depreciable cost equally over the asset’s estimated useful life. When recording depreciation expense, our initial instinct is to debit depreciation expense and credit the Plant and Equipment asset account in the same way prepaids were adjusted with a debit to an expense and a credit to the Prepaid asset account. However, crediting the Plant and Equipment asset account is incorrect. Instead, a contra account called accumulated depreciation must be credited.

A contra account is an account that is related to another account and typically has an opposite normal balance that is subtracted from the balance of its related account on the financial statements. Accumulated depreciation records the amount of the asset’s cost that has been expensed since it was put into use. Accumulated depreciation has a normal credit balance that is subtracted from a Plant and Equipment asset account on the balance sheet. Therefore, accumulated depreciation is a contra-asset account. Contra-asset accounts are asset accounts with a normal credit balance. A contra-asset account is not a liability.

Again, a contra-asset account would be an asset that has a normal credit balance.

Initially, the concept of crediting Accumulated Depreciation may be confusing because of how we learned to adjust prepaids (debit an expense and credit the prepaid). Remember that prepaid items actually get used up and disappear over time. The Plant and Equipment asset account is not credited because, unlike a prepaid, a truck or building does not get used up and does not disappear. The goal in recording depreciation is to match the cost of the asset to the revenues it helped generate. For example, a $50,000 truck that is expected to be used by a business for 4 years will have its cost spread over 4 years. After 4 years, the asset may be sold or replaced.

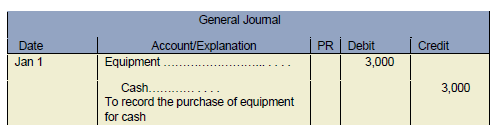

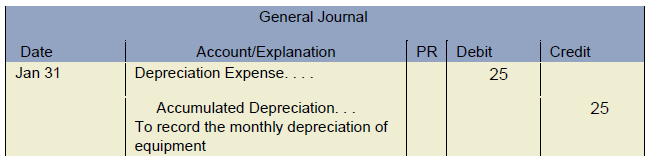

Assume that Big Dog has some equipment that was purchased on January 1 for $3,000. The journal entry to record this purchase would be:

The equipment was recorded as a plant and equipment asset because it has an estimated useful life greater than 1 year. Assume its actual useful life is 10 years (120 months) and the equipment is estimated to be worth $0 at the end of its useful life (residual value of $0).

The equipment was recorded as a plant and equipment asset because it has an estimated useful life greater than 1 year. Assume its actual useful life is 10 years (120 months) and the equipment is estimated to be worth $0 at the end of its useful life (residual value of $0).

(Cost-Estimated Residual Value) ÷ Estimated Useful Life = ($3,000 − $0) ÷ 120 months = $25 months

Note that depreciation is usually rounded to the nearest whole dollar. This is because depreciation is based on estimates — an estimated residual value and an estimated useful life; it is not exact. The following adjusting journal entry is made on January 31:

For financial statement reporting, the asset and contra asset accounts are combined. The net book value of the equipment on the balance sheet is shown as $2,975 ($3,000 − $25). The formula for net book value is Cost – Accumulated Depreciation. Net book value is sometimes shortened to book value or at times referred to as net realizable value.

For financial statement reporting, the asset and contra asset accounts are combined. The net book value of the equipment on the balance sheet is shown as $2,975 ($3,000 − $25). The formula for net book value is Cost – Accumulated Depreciation. Net book value is sometimes shortened to book value or at times referred to as net realizable value.

If depreciation adjustments are not recorded, assets on the balance sheet would be overstated. Additionally, expenses would be understated on the income statement causing net income to be overstated. If net income is overstated, retained earnings on the balance sheet would also be overstated.

It is important to note that land is a long-lived asset. However, it is not depreciated because it does not get used up over time. Therefore, land is often referred to as a non-depreciable asset.

Intangible assets are also depreciated (amortized) on a straight-line basis. We will review intangible assets in detail later in the course.

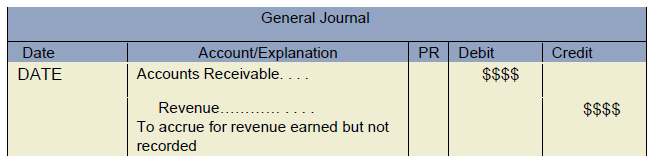

Adjusting for Accrued Revenue Accounts

Accrued revenues are revenues that have been earned but not yet collected or recorded. For example, a bank has numerous notes receivable. Interest is earned on the notes receivable as time passes. At the end of an accounting period, there would be notes receivable where the interest has been earned but not collected or recorded. Accrued revenue could also result from services that have been performed but neither billed nor recorded. As an example, commissions or fees. An adjusting entry is required to show the receivable that exists at the balance sheet date (month or year end) and to record the revenue that has been earned during the period.

Another example of accrued revenue may include timing constraints, with large companies. Large companies may provide services on a daily basis and prepare many invoices during a monthly reporting period. Month-end close time constraints may limit the number of invoices entered and then processed within an accounting system. As a result, not all customer billing amounts (customer invoices) are entered into the accounting financial record-keeping system. An accrued revenue adjustment is needed in order to record the full amount of revenue earned throughout the period since all of the revenue earned has not been entered.

The adjusting entry for accrued revenues is:

Not that cash is NOT included in this adjusting entry!

Not that cash is NOT included in this adjusting entry!

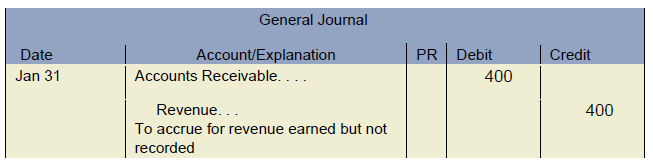

For Big Dog Carworks Corp., assume that on January 31, $400 of repair work was completed for a client but it had not yet been collected or recorded. The company must record the following adjusting entry:

If the adjustment was not recorded, assets on the balance sheet would be understated by $400 and revenues would be understated by the same amount on the income statement.

If the adjustment was not recorded, assets on the balance sheet would be understated by $400 and revenues would be understated by the same amount on the income statement.

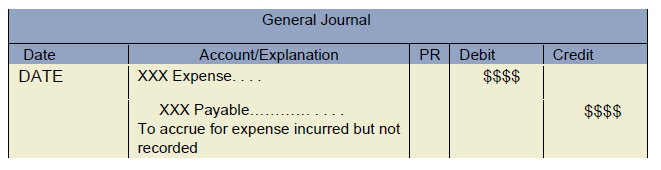

Adjusting for Accrued Expense Accounts

Accrued expenses are expenses that have been incurred but not yet paid or recorded. For example, a utility bill received at the end of the accounting period is likely not payable for 2–3 weeks. Utilities for the period have been used but have not yet been paid or recorded.

The adjusting entry for accrued expenses is:

Where – “XXX” refers to a specific expense that we are accruing. Note that cash is NOT included in this adjusting entry.

Where – “XXX” refers to a specific expense that we are accruing. Note that cash is NOT included in this adjusting entry.

There are several types of expenses that should be accrued. These include interest, wages, taxes, rent and many operating expenses.

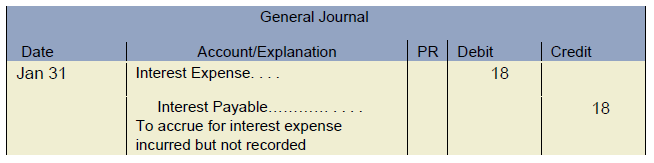

Accruing Interest Expense

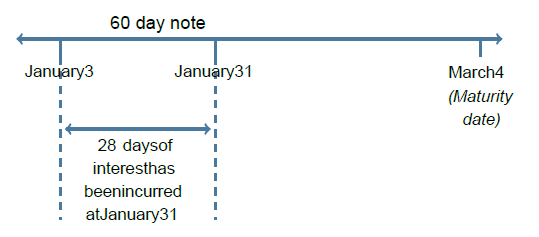

For Big Dog Carworks Corp., the January 31, unadjusted trial balance shows a $6,000 bank loan balance. Assume it is a 4%, 60-day bank loan. It was dated January 3 which means that on January 31, 28 days of interest have accrued (January 31 less January 3 = 28 days) as shown below.

Recall the formula for simple interest:

I = Prt

Interest = Principle × Rate × Time (remember time is always based on 1 year)

In the above example, since the note was taken out on January 3, we will base our calculation on number of days. If a note is taken on the first of the month, use months.

Interest = $6,000 × 4% × (28 ÷ 365) = $18(Rounded to the nearest dollar)

Interest rates are normally expressed as an annual rate. Therefore, 28 days must be divided by 365 days in a year. As stated above, if a loan is taken on the first of a month you can divide by 12 months in a year. The adjusting journal entry is:

Remember – when a company pays back a loan, the company must pay the principle PLUS interest.

Remember – when a company pays back a loan, the company must pay the principle PLUS interest.

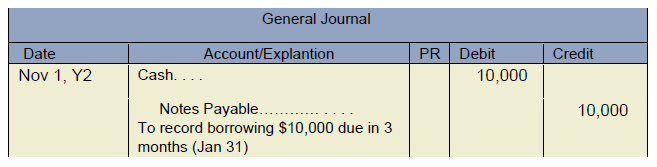

Let’s consider another example that examines the potential life of a short-term note. Suppose on November 1, Y2 a company borrows $10,000 for 3 months (90 days) at an interest rate of 3%. The company has a December 31 year end and only makes adjusting entries at the year end. What are the associated entries?

The first entry would be to record borrowing money on November 1, Y2:

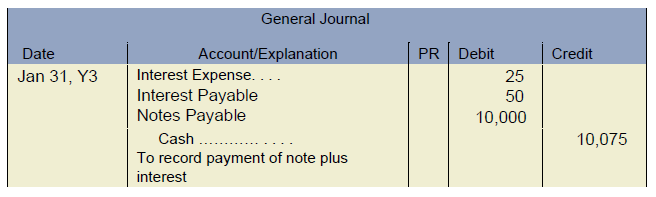

On December 31, Y2, the company would have to accrue interest expense:

On December 31, Y2, the company would have to accrue interest expense:

The calculation of interest expense: Interest = Principle × Rate × Time

Interest = $10000 × 3% × 2⁄12 (Nov. 1 – Dec. 31 = 2 months) = $50

Finally, on January 31, Y3 the loan plus interest for 3 months is due (remember, you have to calculate interest for the month of January):

When recording adjusting entries for accrued interest expense – watch your dates!

When recording adjusting entries for accrued interest expense – watch your dates!

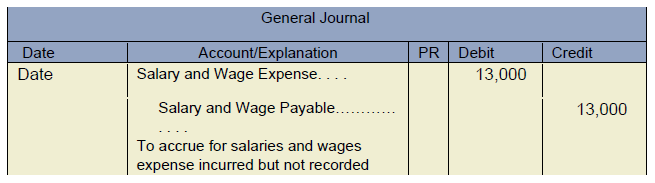

Accruing Salaries and Wages

Employees are often paid for work up to a Friday (last day of the work week – for many). However, pay periods do not normally correspond to the last day of the financial reporting period, so an accrual will have to be made for part of the work week that employees are generating revenue but no expense is recorded.

It’s sometimes helpful to use a calendar to determine the proper amount to accrue with relation to salaries and wages. Remember, there are 52 weeks in a year.

Note – often salaries refer to those paid on an annual basis ($101,400 per year = $1,950 per week). While wages often refer to those employees paid hourly ($20.00 per hour, often a 40 hour work-week). Whether the employee is salary or hourly, the expense still has to be recorded.

Suppose all our employees, on average, earn $6,500 per day. The employees are normally paid weekly, on Friday for work completed on that Friday (in other words, employees are paid current). The reporting period end falls on a Tuesday. That means, we have expenses for Monday and Tuesday that has to be accrued. Our employees worked and generated revenue, so we must match the expense incurred for the revenue generated.

The journal calculation and the journal entry would be:

2 days worked × $6,500 per day = $13,000 accrual.

Note that cash is not included in this entry!

Note that cash is not included in this entry!

Careful with salaries and wages expense accruals. Watch the pay periods (weekly, bi-weekly, semi-monthly, monthly). Also watch for how the employees are paid (current or in arrears).

Accruing for Operating Expenses

Recall that operating expenses are day-to-day expenses that are incurred by an organization. Often, at the end of the accounting reporting period, expenses have been incurred (happened) but an invoice may not have been received. If an invoice has not been received, it is acceptable to make a reasonable estimate of the expense. That occurs often.

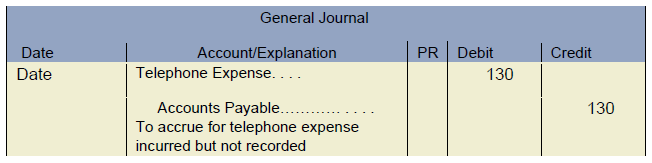

As an example:

During the month, the telephone invoice was not received. Normally, the telephone invoice is approximately $130 per month.

The entry to accrue the estimated telephone invoice would be:

Note – it is not necessary to record each individual operating expense as a separate liability – a credit to either accounts payable or accrued liability is acceptable.

Note – it is not necessary to record each individual operating expense as a separate liability – a credit to either accounts payable or accrued liability is acceptable.

Summary of adjusting entries:

The five types of adjustments discussed in the previous paragraphs are summarized below

Each of the five steps of adjusting entries either debits an expense or credits a revenue. Note – cash is NOT included in any of the above transactions.

Note – cash is NOT included in any of the above transactions.

After all adjusting entries have been prepared and entered, an adjusted trial balance is prepared. The adjusted trial balance can be used to prepare and create the financial statements.

As a reminder, we prepare adjusting entries to obtain proper matching of revenues and expenses and to achieve an accurate statement of assets, liabilities, revenues and expenses.