6.8 Economic Convergence and Catch-Up

This recipe for economic growth—investing in labour productivity, with investments in human capital and technology, as well as increasing physical capital—also applies to other economies.

Some low-income and middle-income economies worldwide have shown a pattern of convergence in which their economies grow faster than those of high-income countries. GDP increased by an average rate of 2.7% per year in the 1990s and 2.3% per year from 2000 to 2008 in the world’s high-income countries, including the United States, Canada, the European Union countries, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand.

Countries can be put in an informal “fast growth club” or “slow growth club.” Fast-growth countries averaged GDP growth (after adjusting for inflation) of at least 5% per year in both the time periods from 1990 to 2000 and from 2000 to 2008. When the economic growth rate in certain countries exceeds the average growth rate of the world’s high-income economies, the middle-income or developing countries (often called emerging economies) may converge with the high-income countries. Slow-growth countries averaged GDP growth of 2% per year or less (after adjusting for inflation) during the same time periods.

Every country has its unique story of investments in human and physical capital, technological gains, market forces, and government policies, but an overall convergence pattern is clear. The low-income countries have GDP growth that is faster than that of the middle-income countries, which in turn have GDP growth that is faster than that of the high-income countries. Two prominent members of the fast-growing club are China and India, which have nearly 40% of the world’s population. Some prominent members of the slow-growth club are high-income countries like France, Germany, Italy, and Japan.

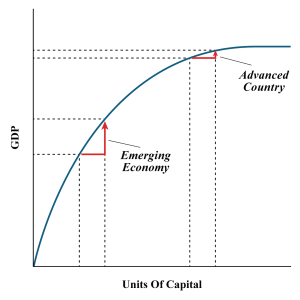

An argument in favour of low-income countries achieving greater worker productivity and economic growth in the future is based on diminishing marginal returns. Even though deepening human and physical capital will tend to increase GDP per capita, the law of diminishing returns suggests that as an economy continues to increase its human and physical capital, the marginal gains to economic growth will diminish. For example, raising the average education level of the population by two years from a tenth-grade level to a high school diploma (while holding all other inputs constant) would produce a certain increase in output. An additional two-year increase, so that the average person had a two-year college degree, would increase output further, but the marginal gain would be smaller. Yet another additional two-year increase in the level of education, so that the average person would have a four-year bachelor’s degree, would increase output further. Still, the marginal increase would again be smaller. A similar lesson holds for physical capital. If the quantity of physical capital available to the average worker increases by $5,000 to $10,000 (again, while keeping all other inputs constant), it will increase the output level. An additional increase from $10,000 to $15,000 will increase output further, but the marginal increase will be smaller.

Low-income countries like China and India tend to have lower levels of human capital and physical capital, so an investment in capital deepening should have a more significant marginal effect in these countries than in high-income countries, where levels of human and physical capital are already relatively high. Diminishing returns implies that low-income economies could converge to the levels that the high-income countries achieve. Additionally, low-income countries may find it easier to improve their technologies than high-income countries. High-income countries must continually invent new technologies, whereas low-income countries can often find ways of applying technology that has already been invented and is well understood.

Optimists argue that many countries have observed the experience of those who have grown more quickly and have learned from it. Moreover, once the people of a country begin to enjoy the benefits of a higher standard of living, they may be more likely to build and support the market-friendly institutions that will help provide this standard of living.

Catch-Up Effect Definition

Catch-up implies circumstances under which relatively low-income countries grow at a faster rate than high-income or advanced economies. Due to this more rapid growth rate, eventually, low-income countries will be able to “catch up” to high-income countries in terms of their per capita GDP.

Overview of Catch-Up Effect

The theory of catch-up effects is also known as the theory of convergence, which argues that relatively low-income or developing economies can achieve the same level of per capita income because adding technology and capital generates higher rates of returns for these countries. Promoting technological advancement yields higher productivity growth, which raises per capita GDP. For example, a company with newly installed computers and skilled workers will experience greater returns than what they used to generate with typewriter machines. An organization operating in an advanced country could upgrade from Dual Core to i9 processor machines, generating greater returns. Still, the rate of productivity growth would not be as high as switching from typewriters to computers.

Following the growth trajectory of developed countries, developing economies can achieve the same growth level in a shorter period by embracing technology and capital deepening.

Attribution

“Chapter 7: Economic Growth” in Introduction to Macroeconomics by J. Zachary Klingensmith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License