6.6 Determinants of Economic Growth in the Long Run

Labour Productivity

Sustained long-term economic growth comes from increases in worker productivity, which essentially means how well we do things. In other words, how efficient is your nation with its time and workers? Labour productivity is the value each employed person creates per unit of their input. The easiest way to comprehend labour productivity is to imagine a Canadian worker who can make ten loaves of bread in an hour versus a U.S. worker who, in the same hour, can make only two loaves of bread. In this fictional example, the Canadians are more productive. More productivity means you can do more in the same amount of time. This, in turn, frees up resources for workers to use elsewhere.

What determines how productive workers are? The answer is pretty intuitive. The first determinant of labour productivity is human capital. Human capital is the accumulated knowledge (from education and experience), skills, and expertise that the average worker in an economy possesses. Typically, the higher the average level of education in an economy, the higher the accumulated human capital and the higher the labour productivity.

The second factor that determines labour productivity is technological change. Technological change is a combination of invention—advances in knowledge—and innovation, which puts that advance to use in a new product or service. For example, the transistor was invented in 1947. It allowed us to miniaturize the footprint of electronic devices and use less power than the tube technology that came before it. Innovations since then have produced smaller and better transistors that are ubiquitous in products as varied as smartphones, computers, and escalators. The development of the transistor has allowed workers to be anywhere with smaller devices. These devices can be used to communicate with other workers, measure product quality or do any other task in less time, improving worker productivity.

The third factor that determines labour productivity is economies of scale. Recall that economies of scale are industries’ cost advantages due to size. Consider again the case of the fictional Canadian worker who could produce ten loaves of bread in an hour. If this difference in productivity was due only to economies of scale, it could be that Canadian workers had access to a large industrial-size oven while the U.S. worker was using a standard residential-size oven.

Sources of Economic Growth: The Aggregate Production Function

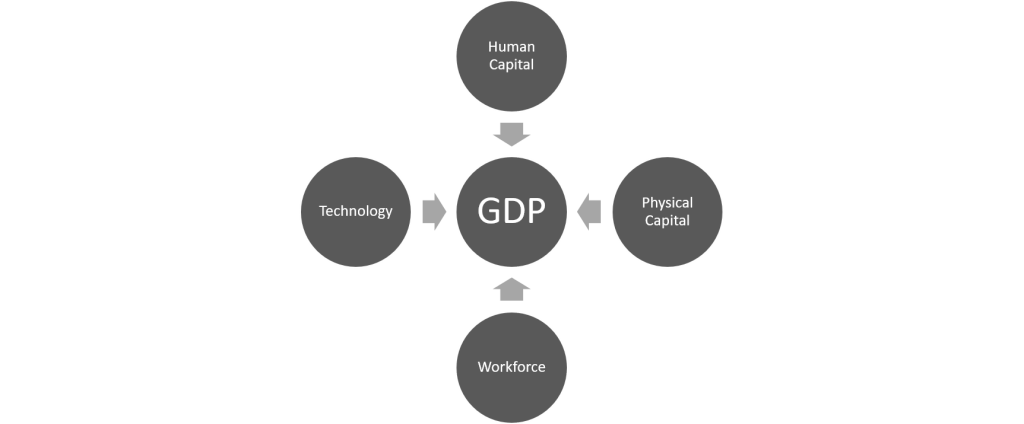

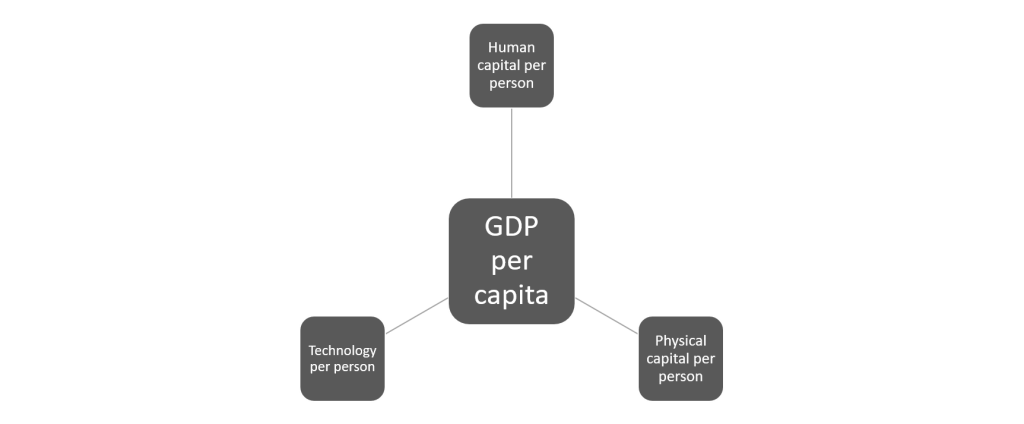

To analyze the sources of economic growth, it is useful to think about a production function, which is the process of turning economic inputs like labour, machinery, and raw materials into outputs like goods and services used by consumers. A microeconomic production function describes the inputs and outputs of a firm or perhaps an industry. In macroeconomics, the connection from inputs to outputs for the entire economy is called an aggregate production function.

Components of the Aggregate Production Function

Figure 6.4 presents two examples of aggregate production functions. In the first production function, shown in Figure 6.4 (a), the output is GDP; in Fig 6.4 (b), the output is GDP per capita.

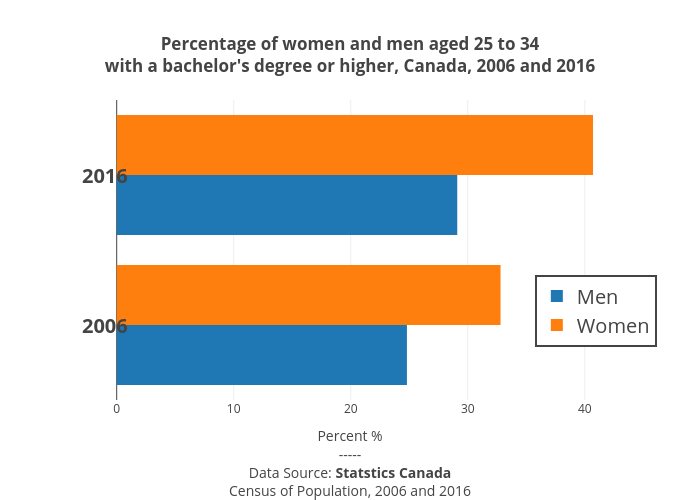

Recall that one way to measure human capital is to look at the average levels of education in an economy. Figure 6.5 illustrates the deepening of human capital for Canadian workers by showing that the proportion of Canada’s population aged 25 to 34 years with a high college degree or diploma has risen between 2006 and 2016, as shown in the graph below. Not only does the current Canadian economy have better-educated workers with more and improved physical capital than it did several decades ago, but these workers have access to more advanced technologies.

When society increases the level of capital per person, we call the result capital deepening. The idea of capital deepening can apply both to additional human capital per worker and to additional physical capital per worker.

| Year | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 24.8 | 32.8 |

| 2016 | 29.1 | 40.7 |

Attribution

“181. Reading: Labor Productivity and Economic Growth” from Macroeconomics by Peter Turner is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

“Chapter 7: Economic Growth” in Introduction to Macroeconomics by J. Zachary Klingensmith is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License