5.6 Why Do We Care About Inflation?

What difference does it make if the average level of prices changes? First, consider the impact of inflation.

|

|

Whether one regards inflation as a “good” thing or a “bad” thing depends very much on one’s economic situation. If you are a borrower, unexpected inflation is a good thing—it reduces the value of money you must repay. It isn’t good if you are a lender because it reduces the value of future payments you will receive. Whatever a particular person’s situation may be, inflation always produces the following effects on the economy: it reduces the value of money and the value of future monetary obligations. It can also create uncertainty about the future.

Suppose you have borrowed $100 from a friend and have agreed to pay it back in one year. During the year, however, prices doubled. That means that when you pay the money back, it will buy only half as much as it could have bought when you borrowed it. That is good for you but tough on the person who lent you the money. Of course, if you and your friend had anticipated such rapid inflation, you might have agreed to pay back a larger sum to adjust for it. When people anticipate inflation, they can adjust for its consequences in determining future obligations. However, unanticipated inflation helps borrowers and hurts lenders. Money loses value when its purchasing power falls. Since inflation is a rise in the level of prices, the amount of goods and services a given amount of money can buy falls with inflation.

Because inflation reduces the purchasing power of money, the threat of future inflation can make people reluctant to lend for long periods. From a lender’s point of view, the danger of a long-term commitment of funds is that future inflation will wipe out the value of the amount that will eventually be paid back. Lenders are reluctant to make such commitments.

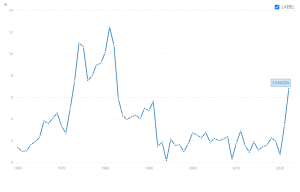

Uncertainty can be particularly pronounced in countries where extremely high inflation is a threat. Hyperinflation is generally defined as an inflation rate in excess of 200% per year.

Several countries have endured episodes of hyperinflation. The worst case was in Hungary immediately after World War II, when Hungary’s price level was tripling every day. The second-worst case of hyperinflation belongs to Zimbabwe, the first country to have experienced hyperinflation in the 21st century. Zimbabwe’s price index was doubling daily: a loaf of bread that cost 200,000 Zimbabwe dollars in February 2008 cost 1.6 trillion Zimbabwe dollars by August (CNN.com, 2018).

Is Deflation good?

As stated by Kate Ashford and Courtney Reilly-Larke (2022),

While deflation may seem like a good thing, it can signal an impending recession and hard economic times. When people feel prices are headed down, they delay purchases in the hopes that they can buy things for less at a later date. But lower spending leads to less income for producers, which can lead to unemployment and higher interest rates due to rising debt. Times of recession or depression often seem to be times when the inflation rate is lower, as in the recession of 1920–1921, the Great Depression, the recession of 1980–1982, and the Great Recession in 2008–2009. There were a few months in 2009 that were deflationary, but not at an annual rate. High levels of unemployment typically accompany recessions, and the total demand for goods falls, pulling the price level down.

Attribution

“5.2 Price-Level Changes” from Principles of Macroeconomics by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License