5.4 Types of Unemployment

Below, we will look at some graphs that show the labour market indicators:

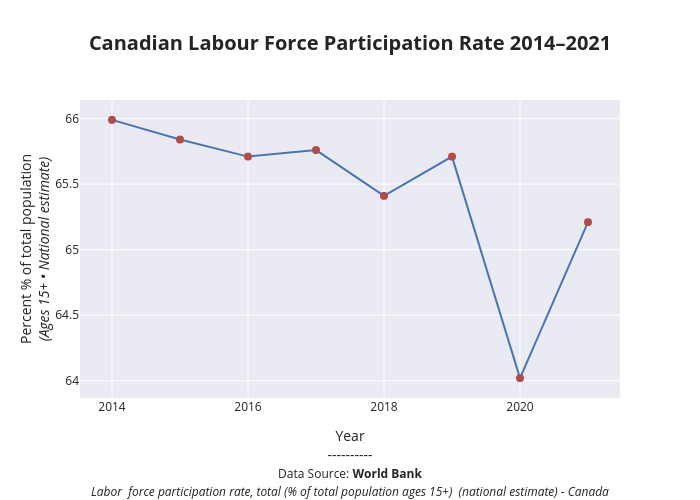

Graph Data Table

| Year | Value |

|---|---|

| 2014 | 65.99 |

| 2015 | 65.84 |

| 2016 | 65.71 |

| 2017 | 65.76 |

| 2018 | 65.41 |

| 2019 | 65.71 |

| 2020 | 64.02 |

| 2021 | 65.21 |

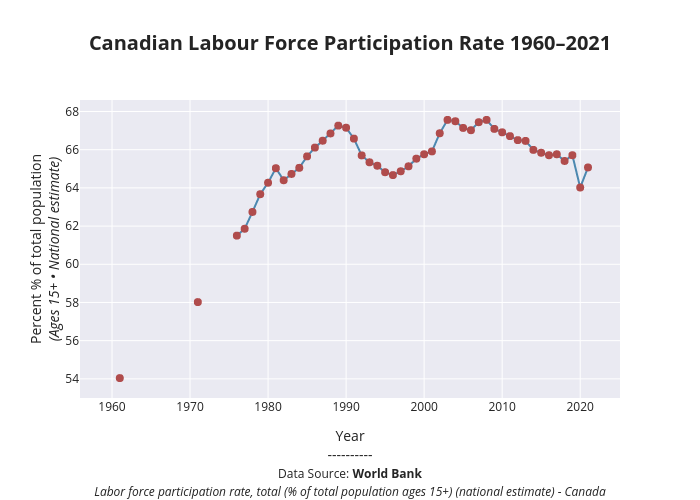

Graph Data Table

| Year | % of total Population |

|---|---|

| 1960 | |

| 1961 | 54.0400009 |

| 1962 | |

| 1963 | |

| 1964 | |

| 1965 | |

| 1966 | |

| 1967 | |

| 1968 | |

| 1969 | |

| 1970 | |

| 1971 | 58.0200005 |

| 1972 | |

| 1973 | |

| 1974 | |

| 1975 | |

| 1976 | 61.5 |

| 1977 | 61.8600006 |

| 1978 | 62.7400017 |

| 1979 | 63.6699982 |

| 1980 | 64.2699966 |

| 1981 | 65.0299988 |

| 1982 | 64.4000015 |

| 1983 | 64.7300034 |

| 1984 | 65.0500031 |

| 1985 | 65.6500015 |

| 1986 | 66.1100006 |

| 1987 | 66.4700012 |

| 1988 | 66.8499985 |

| 1989 | 67.2600021 |

| 1990 | 67.1500015 |

| 1991 | 66.5800018 |

| 1992 | 65.6999969 |

| 1993 | 65.3399963 |

| 1994 | 65.1600037 |

| 1995 | 64.8199997 |

| 1996 | 64.6699982 |

| 1997 | 64.8700027 |

| 1998 | 65.1299973 |

| 1999 | 65.5299988 |

| 2000 | 65.7600021 |

| 2001 | 65.9100037 |

| 2002 | 66.8600006 |

| 2003 | 67.5599976 |

| 2004 | 67.4899979 |

| 2005 | 67.1399994 |

| 2006 | 67.0199966 |

| 2007 | 67.4400024 |

| 2008 | 67.5599976 |

| 2009 | 67.0899963 |

| 2010 | 66.9100037 |

| 2011 | 66.7099991 |

| 2012 | 66.5 |

| 2013 | 66.4599991 |

| 2014 | 65.9899979 |

| 2015 | 65.8399963 |

| 2016 | 65.7099991 |

| 2017 | 65.7600021 |

| 2018 | 65.4100037 |

| 2019 | 65.7099991 |

| 2020 | 64.0199966 |

| 2021 | 65.0699997 |

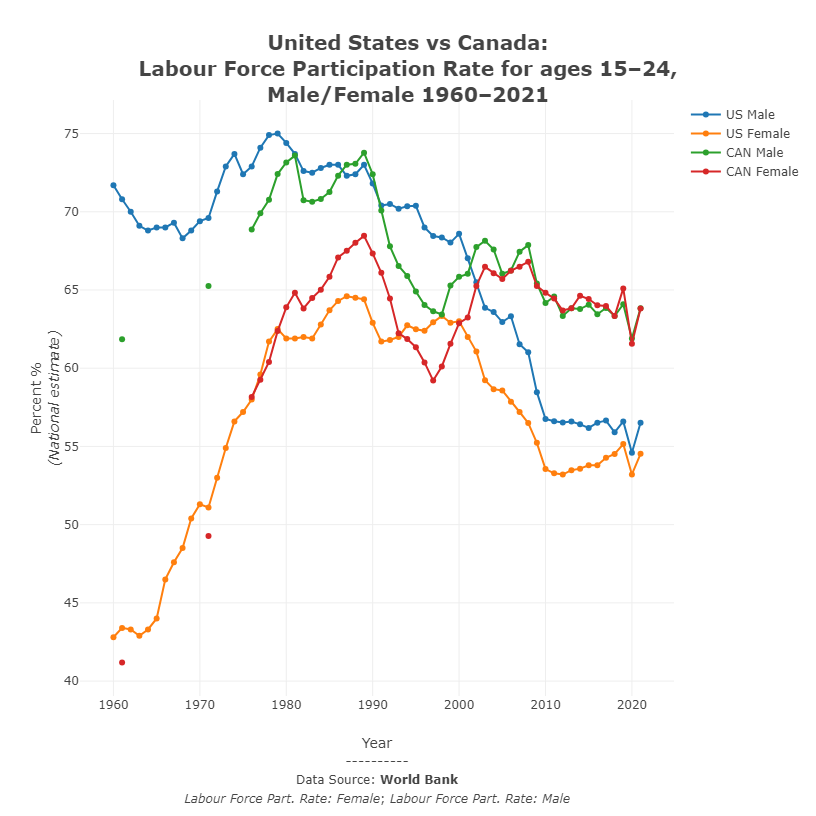

Graph Data Table

| Year | US Male | US Female | CAN Male | CAN Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960 | 71.6999969 | 42.7999992 | ||

| 1961 | 70.8000031 | 43.4000015 | 61.8499985 | 41.1899986 |

| 1962 | 70 | 43.2999992 | ||

| 1963 | 69.0999985 | 42.9000015 | ||

| 1964 | 68.8000031 | 43.2999992 | ||

| 1965 | 69 | 44 | ||

| 1966 | 69 | 46.5 | ||

| 1967 | 69.3000031 | 47.5999985 | ||

| 1968 | 68.3000031 | 48.5 | ||

| 1969 | 68.8000031 | 50.4000015 | ||

| 1970 | 69.4000015 | 51.2999992 | ||

| 1971 | 69.5999985 | 51.0999985 | 65.2600021 | 49.2700005 |

| 1972 | 71.3000031 | 53 | ||

| 1973 | 72.9000015 | 54.9000015 | ||

| 1974 | 73.6999969 | 56.5999985 | ||

| 1975 | 72.4000015 | 57.2000008 | ||

| 1976 | 72.9000015 | 58 | 68.8700027 | 58.1599998 |

| 1977 | 74.0999985 | 59.5999985 | 69.9100037 | 59.2599983 |

| 1978 | 74.9000015 | 61.7000008 | 70.7699966 | 60.4000015 |

| 1979 | 75 | 62.5 | 72.4100037 | 62.3699989 |

| 1980 | 74.4000015 | 61.9000015 | 73.1500015 | 63.8899994 |

| 1981 | 73.6999969 | 61.9000015 | 73.5899963 | 64.8199997 |

| 1982 | 72.5999985 | 62 | 70.7399979 | 63.8199997 |

| 1983 | 72.5 | 61.9000015 | 70.6399994 | 64.4899979 |

| 1984 | 72.8000031 | 62.7999992 | 70.8199997 | 65.0199966 |

| 1985 | 73 | 63.7000008 | 71.2600021 | 65.8399963 |

| 1986 | 73 | 64.3000031 | 72.3099976 | 67.0800018 |

| 1987 | 72.3000031 | 64.5999985 | 73.0100021 | 67.5100021 |

| 1988 | 72.4000015 | 64.5 | 73.0699997 | 68.0199966 |

| 1989 | 73 | 64.4000015 | 73.7799988 | 68.4599991 |

| 1990 | 71.8000031 | 62.9000015 | 72.4000015 | 67.3399963 |

| 1991 | 70.4000015 | 61.7000008 | 70.0800018 | 66.0999985 |

| 1992 | 70.5 | 61.7999992 | 67.7900009 | 64.4599991 |

| 1993 | 70.1999969 | 62 | 66.5400009 | 62.2400017 |

| 1994 | 70.3499985 | 62.7400017 | 65.9000015 | 61.8600006 |

| 1995 | 70.3799973 | 62.4900017 | 64.9000015 | 61.3400002 |

| 1996 | 69 | 62.3899994 | 64.0400009 | 60.3699989 |

| 1997 | 68.4499969 | 62.9300003 | 63.6399994 | 59.2099991 |

| 1998 | 68.3600006 | 63.3400002 | 63.4399986 | 60.1100006 |

| 1999 | 68.0299988 | 62.9099998 | 65.2799988 | 61.5600014 |

| 2000 | 68.5899963 | 63 | 65.8399963 | 62.8800011 |

| 2001 | 67.0299988 | 62 | 66.0299988 | 63.2400017 |

| 2002 | 65.4899979 | 61.0600014 | 67.7399979 | 65.2600021 |

| 2003 | 63.8600006 | 59.2299995 | 68.1500015 | 66.4800034 |

| 2004 | 63.5900002 | 58.6599998 | 67.5899963 | 66.0699997 |

| 2005 | 62.9500008 | 58.5800018 | 66.0299988 | 65.6999969 |

| 2006 | 63.3199997 | 57.8600006 | 66.25 | 66.2300034 |

| 2007 | 61.5299988 | 57.2000008 | 67.4499969 | 66.4899979 |

| 2008 | 61.0200005 | 56.5 | 67.8700027 | 66.8000031 |

| 2009 | 58.4700012 | 55.2299995 | 65.4199982 | 65.2600021 |

| 2010 | 56.75 | 53.54 |

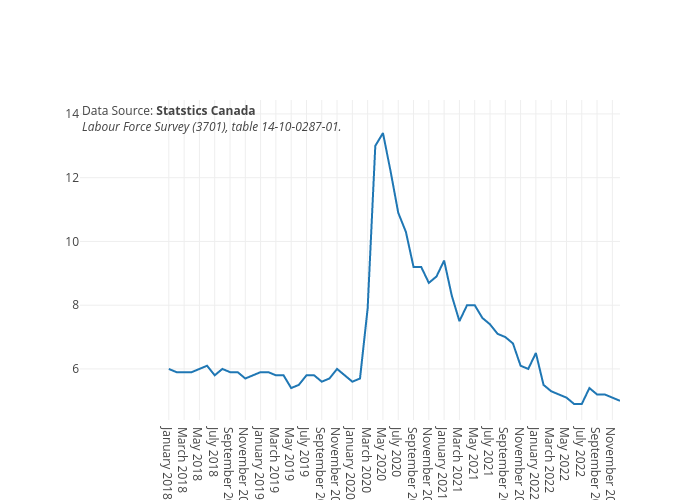

Graph Data Table

| Month | Percentage |

|---|---|

| January 2018 | 6 |

| February 2018 | 5.9 |

| March 2018 | 5.9 |

| April 2018 | 5.9 |

| May 2018 | 6 |

| June 2018 | 6.1 |

| July 2018 | 5.8 |

| August 2018 | 6 |

| September 2018 | 5.9 |

| October 2018 | 5.9 |

| November 2018 | 5.7 |

| December 2018 | 5.8 |

| January 2019 | 5.9 |

| February 2019 | 5.9 |

| March 2019 | 5.8 |

| April 2019 | 5.8 |

| May 2019 | 5.4 |

| June 2019 | 5.5 |

| July 2019 | 5.8 |

| August 2019 | 5.8 |

| September 2019 | 5.6 |

| October 2019 | 5.7 |

| November 2019 | 6 |

| December 2019 | 5.8 |

| January 2020 | 5.6 |

| February 2020 | 5.7 |

| March 2020 | 7.9 |

| April 2020 | 13 |

| May 2020 | 13.4 |

| June 2020 | 12.2 |

| July 2020 | 10.9 |

| August 2020 | 10.3 |

| September 2020 | 9.2 |

| October 2020 | 9.2 |

| November 2020 | 8.7 |

| December 2020 | 8.9 |

| January 2021 | 9.4 |

| February 2021 | 8.3 |

| March 2021 | 7.5 |

| April 2021 | 8 |

| May 2021 | 8 |

| June 2021 | 7.6 |

| July 2021 | 7.4 |

| August 2021 | 7.1 |

| September 2021 | 7 |

| October 2021 | 6.8 |

| November 2021 | 6.1 |

| December 2021 | 6 |

| January 2022 | 6.5 |

| February 2022 | 5.5 |

| March 2022 | 5.3 |

| April 2022 | 5.2 |

| May 2022 | 5.1 |

| June 2022 | 4.9 |

| July 2022 | 4.9 |

| August 2022 | 5.4 |

| September 2022 | 5.2 |

| October 2022 | 5.2 |

| November 2022 | 5.1 |

| December 2022 | 5 |

Explore Further

Workers may find themselves unemployed for different reasons. Each source of unemployment has quite different implications, not only for the workers it affects but also for public policy.

Frictional Unemployment

There’s always a situation where some workers are looking for jobs, and some employers are looking for workers. The workers remain unemployed during the time it takes to match them up. Unemployment that occurs because it takes time for employers and workers to find each other is called frictional unemployment.

The case of college graduates engaged in job searches is a good example of frictional unemployment. Those who did not land a job while still in school will seek work. Most of them will find jobs, but it will take time. During that time, these new graduates will be unemployed. If information about the labour market were costless, firms and potential workers would instantly know everything they needed to know about each other, and there would be no need for searches on the part of workers and firms. There would be no frictional unemployment. But information is costly. Job searches are needed to produce this information, and frictional unemployment exists while the searches continue. The frictional unemployment that results from people moving between jobs in a dynamic economy may account for one to two percentage points of total unemployment.

The government may attempt to reduce frictional unemployment by focusing on its source: information costs. Many provincial agencies, for example, offer job search assistance. They encourage firms seeking workers and workers seeking jobs to register with them. To the extent that such efforts make labour-market information more readily available, they reduce frictional unemployment.

Structural Unemployment

The structurally unemployed are individuals who have no jobs because they lack skills valued by the labour market, either because demand has shifted away from the skills they do have or because they never learned any skills. An example of the former would be the unemployment among aerospace engineers after the U.S. space program downsized in the 1970s. An example of the latter would be high school dropouts.

Some people worry that technology causes structural unemployment. In the past, new technologies have put lower-skilled employees out of work, but at the same time, they create demand for higher-skilled workers to use the new technologies. Education seems to be the key in minimizing the amount of structural unemployment. Individuals who have degrees can be retrained if they become structurally unemployed. That option is more limited for people with no skills and little education.

Structural unemployment can also result from geographical mismatches. Economic activity may be booming in one region and slumping in another. It will take time for unemployed workers to relocate and find new jobs. And poor or costly transportation may block some urban residents from obtaining jobs only a few miles away.

Public policy responses to structural unemployment generally focus on job training and education to equip workers with the skills firms demand. The government publishes regional labour-market information, helping to inform unemployed workers of where jobs can be found. Although government programs may reduce frictional and structural unemployment, they cannot eliminate it.

Cyclical Unemployment

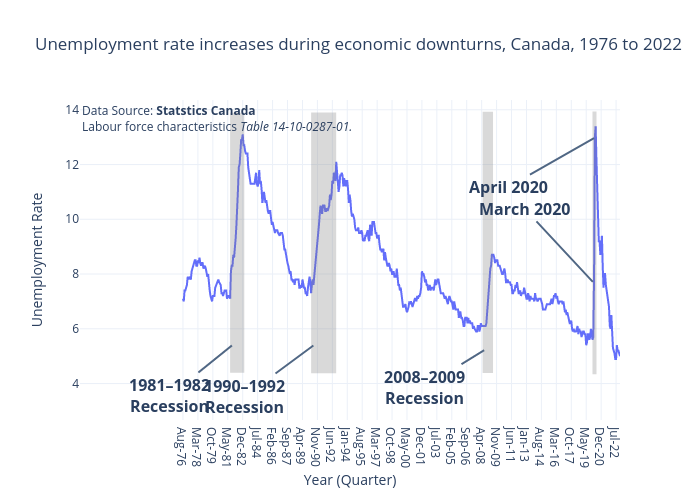

The economy faces a boom and bust, which we call the business cycle. In certain periods, real GDP increases, and in other periods, real GDP decreases. You may recall from Chapter 4 that the increase in GDP is called economic expansion, and the decrease in GDP is called economic recession. Unemployment changes with changes in GDP. People will likely be laid off from jobs when the economy faces a recession. This triggers cyclical unemployment. Therefore, cyclical unemployment is a type of unemployment that changes with the business cycle. During a recession, cyclical unemployment increases, and cyclical unemployment decreases during the expansionary or recovery phase of the economy.

Graph Data Table

| Date | Percentage |

|---|---|

| August 1976 | 7.1 |

| September 1976 | 7 |

| October 1976 | 7.4 |

| November 1976 | 7.4 |

| December 1976 | 7.5 |

| January 1977 | 7.6 |

| February 1977 | 7.9 |

| March 1977 | 7.8 |

| April 1977 | 7.9 |

| May 1977 | 7.8 |

| June 1977 | 7.8 |

| July 1977 | 8.1 |

| August 1977 | 8.2 |

| September 1977 | 8.3 |

| October 1977 | 8.4 |

| November 1977 | 8.5 |

| December 1977 | 8.5 |

| January 1978 | 8.3 |

| February 1978 | 8.3 |

| March 1978 | 8.5 |

| April 1978 | 8.4 |

| May 1978 | 8.6 |

| June 1978 | 8.4 |

| July 1978 | 8.3 |

| August 1978 | 8.4 |

| September 1978 | 8.4 |

| October 1978 | 8.2 |

| November 1978 | 8.3 |

| December 1978 | 8.3 |

| January 1979 | 8.2 |

| February 1979 | 8 |

| March 1979 | 7.9 |

| April 1979 | 8 |

| May 1979 | 7.6 |

| June 1979 | 7.4 |

| July 1979 | 7.2 |

| August 1979 | 7.1 |

| September 1979 | 7 |

| October 1979 | 7.2 |

| November 1979 | 7.2 |

| December 1979 | 7.2 |

| January 1980 | 7.5 |

| February 1980 | 7.6 |

| March 1980 | 7.6 |

| April 1980 | 7.7 |

| May 1980 | 7.8 |

| June 1980 | 7.7 |

| July 1980 | 7.6 |

| August 1980 | 7.6 |

| September 1980 | 7.3 |

| October 1980 | 7.3 |

| November 1980 | 7.2 |

| December 1980 | 7.3 |

| January 1981 | 7.4 |

| February 1981 | 7.4 |

| March 1981 | 7.4 |

| April 1981 | 7.1 |

| May 1981 | 7.2 |

| June 1981 | 7.2 |

| July 1981 | 7.2 |

| August 1981 | 7.1 |

| September 1981 | 8.1 |

| October 1981 | 8.3 |

| November 1981 | 8.3 |

| December 1981 | 8.7 |

| January 1982 | 8.6 |

| February 1982 | 8.9 |

| March 1982 | 9.3 |

| April 1982 | 9.8 |

| May 1982 | 10.3 |

| June 1982 | 11.1 |

| July 1982 | 11.9 |

| August 1982 | 12 |

| September 1982 | 12.4 |

| October 1982 | 12.9 |

| November 1982 | 12.9 |

| December 1982 | 13.1 |

| January 1983 | 12.7 |

| February 1983 | 12.7 |

| March 1983 | 12.5 |

| April 1983 | 12.4 |

| May 1983 | 12.4 |

| June 1983 | 12.4 |

| July 1983 | 11.9 |

| August 1983 | 11.7 |

| September 1983 | 11.4 |

| October 1983 | 11.3 |

| November 1983 | 11.3 |

| December 1983 | 11.3 |

| January 1984 | 11.3 |

| February 1984 | 11.3 |

| March 1984 | 11.3 |

| April 1984 | 11.5 |

| May 1984 | 11.7 |

| June 1984 | 11.3 |

| July 1984 | 11.2 |

| August 1984 | 11.3 |

| September 1984 | 11.8 |

| October 1984 | 11.3 |

| November 1984 | 11.4 |

| December 1984 | 11.1 |

| January 1985 | 10.6 |

| February 1985 | 10.8 |

| March 1985 | 11 |

| April 1985 | 10.8 |

| May 1985 | 10.6 |

| June 1985 | 10.7 |

| July 1985 | 10.4 |

| August 1985 | 10.3 |

| September 1985 | 10.2 |

| October 1985 | 10.3 |

| November 1985 | 10.3 |

| December 1985 | 10.1 |

| January 1986 | 9.8 |

| February 1986 | 9.9 |

| March 1986 | 9.8 |

| April 1986 | 9.7 |

| May 1986 | 9.5 |

| June 1986 | 9.6 |

| July 1986 | 9.6 |

| August 1986 | 9.6 |

| September 1986 | 9.5 |

| October 1986 | 9.4 |

| November 1986 | 9.4 |

| December 1986 | 9.5 |

| January 1987 | 9.5 |

| February 1987 | 9.5 |

| March 1987 | 9.4 |

| April 1987 | 9.2 |

| May 1987 | 8.9 |

| June 1987 | 8.9 |

| July 1987 | 8.7 |

| August 1987 | 8.6 |

| September 1987 | 8.4 |

| October 1987 | 8.3 |

| November 1987 | 8.2 |

| December 1987 | 8 |

| January 1988 | 8.1 |

| February 1988 | 7.8 |

| March 1988 | 7.8 |

| April 1988 | 7.7 |

| May 1988 | 7.8 |

| June 1988 | 7.6 |

| July 1988 | 7.8 |

| August 1988 | 7.8 |

| September 1988 | 7.8 |

| October 1988 | 7.8 |

| November 1988 | 7.8 |

| December 1988 | 7.5 |

| January 1989 | 7.5 |

| February 1989 | 7.6 |

| March 1989 | 7.5 |

| April 1989 | 7.8 |

| May 1989 | 7.7 |

| June 1989 | 7.5 |

| July 1989 | 7.5 |

| August 1989 | 7.3 |

| September 1989 | 7.3 |

| October 1989 | 7.2 |

| November 1989 | 7.5 |

| December 1989 | 7.7 |

| January 1990 | 7.9 |

| February 1990 | 7.7 |

| March 1990 | 7.3 |

| April 1990 | 7.6 |

| May 1990 | 7.8 |

| June 1990 | 7.6 |

| July 1990 | 7.9 |

| August 1990 | 8.1 |

| September 1990 | 8.5 |

| October 1990 | 8.8 |

| November 1990 | 9.1 |

| December 1990 | 9.5 |

| January 1991 | 9.8 |

| February 1991 | 10.2 |

| March 1991 | 10.5 |

| April 1991 | 10.3 |

| May 1991 | 10.2 |

| June 1991 | 10.5 |

| July 1991 | 10.5 |

| August 1991 | 10.5 |

| September 1991 | 10.3 |

| October 1991 | 10.3 |

| November 1991 | 10.4 |

| December 1991 | 10.3 |

| January 1992 | 10.4 |

| February 1992 | 10.5 |

| March 1992 | 10.9 |

| April 1992 | 10.7 |

| May 1992 | 10.9 |

| June 1992 | 11.4 |

| July 1992 | 11.3 |

| August 1992 | 11.7 |

| September 1992 | 11.6 |

| October 1992 | 11.4 |

| November 1992 | 12.1 |

| December 1992 | 11.7 |

| January 1993 | 11.2 |

| February 1993 | 11 |

| March 1993 | 11.2 |

| April 1993 | 11.6 |

| May 1993 | 11.6 |

| June 1993 | 11.7 |

| July 1993 | 11.6 |

| August 1993 | 11.2 |

| September 1993 | 11.5 |

| October 1993 | 11.3 |

| November 1993 | 11.2 |

| December 1993 | 11.4 |

| January 1994 | 11.4 |

| February 1994 | 11.1 |

| March 1994 | 10.6 |

| April 1994 | 10.9 |

| May 1994 | 10.7 |

| June 1994 | 10.3 |

| July 1994 | 10.1 |

| August 1994 | 10.2 |

| September 1994 | 10.1 |

| October 1994 | 10 |

| November 1994 | 9.7 |

| December 1994 | 9.6 |

| January 1995 | 9.6 |

| February 1995 | 9.6 |

| March 1995 | 9.7 |

| April 1995 | 9.5 |

| May 1995 | 9.5 |

| June 1995 | 9.5 |

| July 1995 | 9.6 |

| August 1995 | 9.5 |

| September 1995 | 9.2 |

| October 1995 | 9.3 |

| November 1995 | 9.2 |

| December 1995 | 9.4 |

| January 1996 | 9.4 |

| February 1996 | 9.5 |

| March 1996 | 9.6 |

| April 1996 | 9.3 |

| May 1996 | 9.2 |

| June 1996 | 9.8 |

| July 1996 | 9.7 |

| August 1996 | 9.4 |

| September 1996 | 9.9 |

| October 1996 | 9.9 |

| November 1996 | 9.9 |

| December 1996 | 9.7 |

| January 1997 | 9.5 |

| February 1997 | 9.5 |

| March 1997 | 9.3 |

| April 1997 | 9.4 |

| May 1997 | 9.4 |

| June 1997 | 9.1 |

| July 1997 | 8.9 |

| August 1997 | 8.9 |

| September 1997 | 8.8 |

| October 1997 | 8.9 |

| November 1997 | 8.9 |

| December 1997 | 8.5 |

| January 1998 | 8.8 |

| February 1998 | 8.6 |

| March 1998 | 8.4 |

| April 1998 | 8.3 |

| May 1998 | 8.3 |

| June 1998 | 8.4 |

| July 1998 | 8.3 |

| August 1998 | 8.1 |

| September 1998 | 8.2 |

| October 1998 | 8 |

| November 1998 | 8 |

| December 1998 | 8.1 |

| January 1999 | 7.9 |

| February 1999 | 7.9 |

| March 1999 | 7.9 |

| April 1999 | 8.2 |

| May 1999 | 7.9 |

| June 1999 | 7.6 |

| July 1999 | 7.6 |

| August 1999 | 7.4 |

| September 1999 | 7.5 |

| October 1999 | 7.2 |

| November 1999 | 6.9 |

| December 1999 | 6.8 |

| January 2000 | 6.8 |

| February 2000 | 6.9 |

| March 2000 | 6.9 |

| April 2000 | 6.7 |

| May 2000 | 6.6 |

| June 2000 | 6.7 |

| July 2000 | 6.8 |

| August 2000 | 7 |

| September 2000 | 6.9 |

| October 2000 | 7 |

| November 2000 | 6.9 |

| December 2000 | 6.8 |

| January 2001 | 6.9 |

| February 2001 | 7 |

| March 2001 | 7.1 |

| April 2001 | 7.1 |

| May 2001 | 7 |

| June 2001 | 7.2 |

| July 2001 | 7.1 |

| August 2001 | 7.2 |

| September 2001 | 7.2 |

| October 2001 | 7.3 |

| November 2001 | 7.5 |

| December 2001 | 8.1 |

| January 2002 | 8 |

| February 2002 | 8 |

| March 2002 | 7.9 |

| April 2002 | 7.7 |

| May 2002 | 7.8 |

| June 2002 | 7.6 |

| July 2002 | 7.6 |

| August 2002 | 7.4 |

| September 2002 | 7.5 |

| October 2002 | 7.6 |

| November 2002 | 7.4 |

| December 2002 | 7.5 |

| January 2003 | 7.5 |

| February 2003 | 7.5 |

| March 2003 | 7.4 |

| April 2003 | 7.6 |

| May 2003 | 7.8 |

| June 2003 | 7.6 |

| July 2003 | 7.7 |

| August 2003 | 7.8 |

| September 2003 | 7.8 |

| October 2003 | 7.6 |

| November 2003 | 7.4 |

| December 2003 | 7.3 |

| January 2004 | 7.3 |

| February 2004 | 7.3 |

| March 2004 | 7.3 |

| April 2004 | 7.2 |

| May 2004 | 7.1 |

| June 2004 | 7.2 |

| July 2004 | 7.1 |

| August 2004 | 7 |

| September 2004 | 6.9 |

| October 2004 | 7.1 |

| November 2004 | 7.2 |

| December 2004 | 7.1 |

| January 2005 | 7 |

| February 2005 | 7 |

| March 2005 | 6.9 |

| April 2005 | 6.7 |

| May 2005 | 7 |

| June 2005 | 6.8 |

| July 2005 | 6.7 |

| August 2005 | 6.7 |

| September 2005 | 6.7 |

| October 2005 | 6.7 |

| November 2005 | 6.4 |

| December 2005 | 6.6 |

| January 2006 | 6.6 |

| February 2006 | 6.4 |

| March 2006 | 6.4 |

| April 2006 | 6.3 |

| May 2006 | 6.1 |

| June 2006 | 6.1 |

| July 2006 | 6.4 |

| August 2006 | 6.4 |

| September 2006 | 6.4 |

| October 2006 | 6.2 |

| November 2006 | 6.4 |

| December 2006 | 6.2 |

| January 2007 | 6.3 |

| February 2007 | 6.2 |

| March 2007 | 6.2 |

| April 2007 | 6.2 |

| May 2007 | 6 |

| June 2007 | 6.1 |

| July 2007 | 6 |

| August 2007 | 5.9 |

| September 2007 | 5.9 |

| October 2007 | 5.9 |

| November 2007 | 6.1 |

| December 2007 | 6.1 |

| January 2008 | 5.9 |

| February 2008 | 6 |

| March 2008 | 6.2 |

| April 2008 | 6.1 |

| May 2008 | 6.1 |

| June 2008 | 6.1 |

| July 2008 | 6.1 |

| August 2008 | 6.1 |

| September 2008 | 6.1 |

| October 2008 | 6.2 |

| November 2008 | 6.6 |

| December 2008 | 6.9 |

| January 2009 | 7.4 |

| February 2009 | 8 |

| March 2009 | 8.2 |

| April 2009 | 8.3 |

| May 2009 | 8.7 |

| June 2009 | 8.7 |

| July 2009 | 8.7 |

| August 2009 | 8.6 |

| September 2009 | 8.4 |

| October 2009 | 8.5 |

| November 2009 | 8.5 |

| December 2009 | 8.5 |

| January 2010 | 8.3 |

| February 2010 | 8.3 |

| March 2010 | 8.3 |

| April 2010 | 8.2 |

| May 2010 | 8.1 |

| June 2010 | 8 |

| July 2010 | 8 |

| August 2010 | 8.1 |

| September 2010 | 8.2 |

| October 2010 | 8 |

| November 2010 | 7.7 |

| December 2010 | 7.7 |

| January 2011 | 7.8 |

| February 2011 | 7.7 |

| March 2011 | 7.7 |

| April 2011 | 7.7 |

| May 2011 | 7.6 |

| June 2011 | 7.6 |

| July 2011 | 7.3 |

| August 2011 | 7.3 |

| September 2011 | 7.4 |

| October 2011 | 7.4 |

| November 2011 | 7.6 |

| December 2011 | 7.5 |

| January 2012 | 7.7 |

| February 2012 | 7.5 |

| March 2012 | 7.3 |

| April 2012 | 7.3 |

| May 2012 | 7.4 |

| June 2012 | 7.2 |

| July 2012 | 7.3 |

| August 2012 | 7.3 |

| September 2012 | 7.3 |

| October 2012 | 7.5 |

| November 2012 | 7.4 |

| December 2012 | 7.3 |

| January 2013 | 7.1 |

| February 2013 | 7.1 |

| March 2013 | 7.3 |

| April 2013 | 7.2 |

| May 2013 | 7 |

| June 2013 | 7.2 |

| July 2013 | 7.1 |

| August 2013 | 7.1 |

| September 2013 | 7.1 |

| October 2013 | 7.1 |

| November 2013 | 7 |

| December 2013 | 7.3 |

| January 2014 | 7.1 |

| February 2014 | 7.1 |

| March 2014 | 7 |

| April 2014 | 7.1 |

| May 2014 | 7.1 |

| June 2014 | 7.1 |

| July 2014 | 7.1 |

| August 2014 | 7 |

| September 2014 | 6.9 |

| October 2014 | 6.7 |

| November 2014 | 6.7 |

| December 2014 | 6.7 |

| January 2015 | 6.7 |

| February 2015 | 6.8 |

| March 2015 | 6.9 |

| April 2015 | 6.9 |

| May 2015 | 6.9 |

| June 2015 | 6.9 |

| July 2015 | 6.9 |

| August 2015 | 7 |

| September 2015 | 7.1 |

| October 2015 | 6.9 |

| November 2015 | 7.1 |

| December 2015 | 7.2 |

| January 2016 | 7.2 |

| February 2016 | 7.3 |

| March 2016 | 7.1 |

| April 2016 | 7.2 |

| May 2016 | 7 |

| June 2016 | 6.9 |

| July 2016 | 7 |

| August 2016 | 7 |

| September 2016 | 7 |

| October 2016 | 7 |

| November 2016 | 6.9 |

| December 2016 | 7 |

| January 2017 | 6.8 |

| February 2017 | 6.6 |

| March 2017 | 6.7 |

| April 2017 | 6.5 |

| May 2017 | 6.6 |

| June 2017 | 6.5 |

| July 2017 | 6.3 |

| August 2017 | 6.2 |

| September 2017 | 6.2 |

| October 2017 | 6.3 |

| November 2017 | 6 |

| December 2017 | 5.9 |

| January 2018 | 6 |

| February 2018 | 5.9 |

| March 2018 | 5.9 |

| April 2018 | 5.9 |

| May 2018 | 6 |

| June 2018 | 6.1 |

| July 2018 | 5.8 |

| August 2018 | 6 |

| September 2018 | 5.9 |

| October 2018 | 5.9 |

| November 2018 | 5.7 |

| December 2018 | 5.8 |

| January 2019 | 5.9 |

| February 2019 | 5.9 |

| March 2019 | 5.8 |

| April 2019 | 5.8 |

| May 2019 | 5.4 |

| June 2019 | 5.5 |

| July 2019 | 5.8 |

| August 2019 | 5.8 |

| September 2019 | 5.6 |

| October 2019 | 5.7 |

| November 2019 | 6 |

| December 2019 | 5.8 |

| January 2020 | 5.6 |

| February 2020 | 5.7 |

| March 2020 | 7.9 |

| April 2020 | 13 |

| May 2020 | 13.4 |

| June 2020 | 12.2 |

| July 2020 | 10.9 |

| August 2020 | 10.3 |

| September 2020 | 9.2 |

| October 2020 | 9.2 |

| November 2020 | 8.7 |

| December 2020 | 8.9 |

| January 2021 | 9.4 |

| February 2021 | 8.3 |

| March 2021 | 7.5 |

| April 2021 | 8 |

| May 2021 | 8 |

| June 2021 | 7.6 |

| July 2021 | 7.4 |

| August 2021 | 7.1 |

| September 2021 | 7 |

| October 2021 | 6.8 |

| November 2021 | 6.1 |

| December 2021 | 6 |

| January 2022 | 6.5 |

| February 2022 | 5.5 |

| March 2022 | 5.3 |

| April 2022 | 5.2 |

| May 2022 | 5.1 |

| June 2022 | 4.9 |

| July 2022 | 4.9 |

| August 2022 | 5.4 |

| September 2022 | 5.2 |

| October 2022 | 5.2 |

| November 2022 | 5.1 |

| December 2022 | 5 |

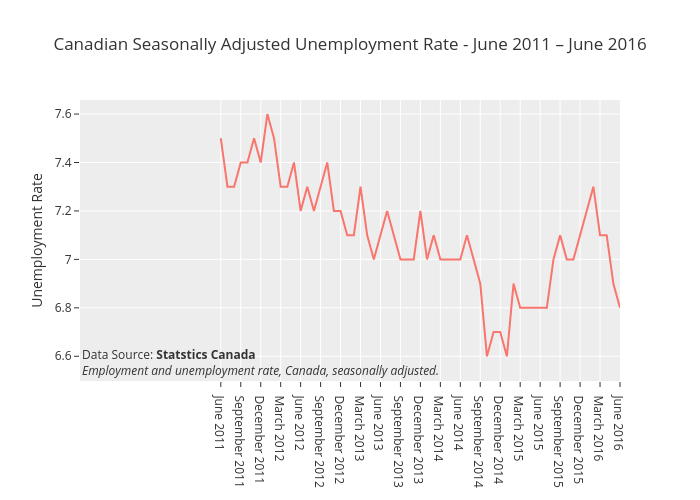

Seasonal Unemployment

Seasonal unemployment may be seen as a kind of structural unemployment since it is a type of unemployment that is linked to certain kinds of jobs (construction work, migratory farm work, and fishing). The most-cited official unemployment measures erase this kind of unemployment from the statistics using “seasonal adjustment” techniques.

Graph Data Table

| Month | Percentage |

|---|---|

| June 2011 | 7.5 |

| July 2011 | 7.3 |

| August 2011 | 7.3 |

| September 2011 | 7.4 |

| October 2011 | 7.4 |

| November 2011 | 7.5 |

| December 2011 | 7.4 |

| January 2012 | 7.6 |

| February 2012 | 7.5 |

| March 2012 | 7.3 |

| April 2012 | 7.3 |

| May 2012 | 7.4 |

| June 2012 | 7.2 |

| July 2012 | 7.3 |

| August 2012 | 7.2 |

| September 2012 | 7.3 |

| October 2012 | 7.4 |

| November 2012 | 7.2 |

| December 2012 | 7.2 |

| January 2013 | 7.1 |

| February 2013 | 7.1 |

| March 2013 | 7.3 |

| April 2013 | 7.1 |

| May 2013 | 7 |

| June 2013 | 7.1 |

| July 2013 | 7.2 |

| August 2013 | 7.1 |

| September 2013 | 7 |

| October 2013 | 7 |

| November 2013 | 7 |

| December 2013 | 7.2 |

| January 2014 | 7 |

| February 2014 | 7.1 |

| March 2014 | 7 |

| April 2014 | 7 |

| May 2014 | 7 |

| June 2014 | 7 |

| July 2014 | 7.1 |

| August 2014 | 7 |

| September 2014 | 6.9 |

| October 2014 | 6.6 |

| November 2014 | 6.7 |

| December 2014 | 6.7 |

| January 2015 | 6.6 |

| February 2015 | 6.9 |

| March 2015 | 6.8 |

| April 2015 | 6.8 |

| May 2015 | 6.8 |

| June 2015 | 6.8 |

| July 2015 | 6.8 |

| August 2015 | 7 |

| September 2015 | 7.1 |

| October 2015 | 7 |

| November 2015 | 7 |

| December 2015 | 7.1 |

| January 2016 | 7.2 |

| February 2016 | 7.3 |

| March 2016 | 7.1 |

| April 2016 | 7.1 |

| May 2016 | 6.9 |

| June 2016 | 6.8 |

Natural Rate of Unemployment

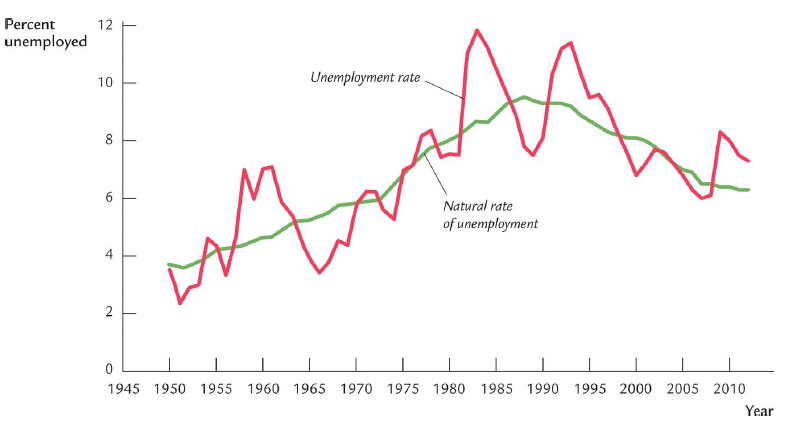

When the aggregate economy faces only frictional and structural unemployment, we call that kind of unemployment the Natural Rate of Unemployment. When the economy operates at a Natural Rate of Unemployment, there is NO cyclical Unemployment; all the existing unemployment is only frictional and structural.

The natural unemployment rate is related to two other important concepts: full employment and potential real GDP. Economists consider the economy to be at full employment when the actual unemployment rate is equal to the natural unemployment rate. In other words, full employment implies a situation when the economy faces only frictional and structural unemployment. So, the economy operating at natural unemployment means the economy is at full employment. When the economy is at full employment, real GDP is equal to potential real GDP. By contrast, when the economy is below full employment, the unemployment rate is greater than the natural unemployment rate, and real GDP is less than the potential. Finally, when the economy is above full employment, the unemployment rate is less than the natural unemployment rate, and the real GDP is greater than the potential. Operating above potential is only possible briefly since it is analogous to all workers working overtime.

Attribution

“5.3 Unemployment” from Principles of Macroeconomics by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License