2.5 PPF and International Trade

One of the most important implications of the concepts of the production possibilities curve relates to international trade. The evidence that international trade confers overall benefits on economies is solid. Trade has accompanied economic growth in Canada and around the world. Many economies that have shown the most rapid growth in the last few decades — for example, Japan, South Korea, China, and India — have done so by dramatically orienting their economies toward international trade. To understand the benefits of trade or why we trade in the first place, we need to understand the concepts of comparative and absolute advantage.

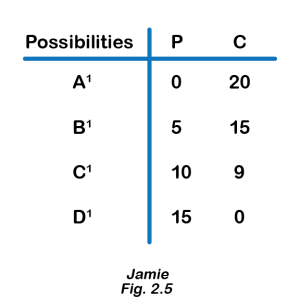

In the previous section on the production possibilities frontier, we stated that points outside the PPF were impossible given our constraints. With trade, these constraints can change. Continuing the pineapple and crab example from Fig 2.2, suppose another person, Jamie, becomes stranded on the island with you. You could choose to avoid him and live your own separate lives, or you could work together to improve each other’s well-being. It turns out Jamie has different skills than you – he is better at producing crabs, and you are better at growing pineapples. Jamie’s production possibilities are shown in the table below (Fig 2.5).

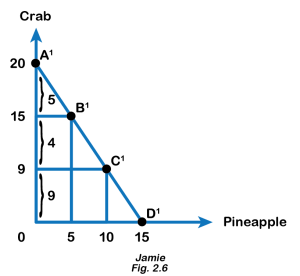

In this case, where one person or group is better at producing a good, we say they have an Absolute Advantage in producing the good. In this example, from Fig 2.2 and 2.5, Jamie has an absolute advantage in the production of crab as he can produce a maximum of 20 crabs while you can produce a maximum of 15 crabs, and you have an absolute advantage in producing pineapples as you can grow a maximum of 30 pineapples while Jamie can produce a maximum of 15 only. The graph below (Fig 2.6) shows Jamie’s production possibilities.

The basis for trade is Comparative Advantage. When one can produce a good at a lower opportunity cost than another, the person is said to be efficient or have a comparative advantage in producing that good.

Finding Out Comparative Advantage

Refer to Fig 2.3. When you produce 15 crabs, you give up 30 pineapples. So, your opportunity cost of producing one crab is two pineapples. Referring to Fig 2.6, when Jamie produces 20 crabs, he gives up 15 pineapples. So Jamie’s opportunity cost of producing one crab is 0.75 pineapples. Because Jamie has a lower opportunity cost in producing crabs, he has a comparative advantage in crabs. Similarly, we can find your opportunity cost in producing one pineapple is 0.5 crabs, and Jamie’s opportunity cost is 1.33. Therefore, we can infer you have a lower opportunity cost or comparative advantage in producing pineapples.

Comparative Advantage and Specialization

When one has a comparative advantage in producing a good, that person should specialize in producing that good. This specialization in production results in gains from trade, as each person or country can focus on what it can produce at the lowest cost and trade it with its partner.

Even though Jamie had the absolute advantage in crabs, his opportunity cost of producing crabs was still higher since opportunity or marginal cost is based on a trade-off between the two goods. We can liken this example to trade between Canada and a developing country. Canada may be better at producing both computers and textiles (the absolute advantage), but the advantages we have in producing computers are far more significant. Any hour we have to give up to produce textiles comes at a much higher cost than it would to a developing country, giving us the comparative advantage at producing computers and the developing country the advantage at producing textiles.

The island example is no different. Even though Jamie is better at producing pineapples, what Jamie is an expert at is producing crabs, so having to give up time spent catching crabs comes at a high cost. Therefore, you should specialize in producing pineapples and export them to Jamie, while Jamie should produce crabs and export them to you.

Attribution

“2.3 Trade” in Principles of Microeconomics by Dr. Emma Hutchinson, University of Victoria is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.