Chapter 12: Inflammatory & Infected Wounds

Authors:

- Muskaan Sachdeva (BHSc)1,

- Afsaneh Alavi (MD, FRCPC)1,2

Learning Objectives

- To review the clinical features and management strategies of Hidradenitis Suppurativa

- To review the clinical features and management strategies of Pyoderma Gangrenosum

- To review the clinical features and management strategies of Vasculitis

Hidradenitis suppurativa

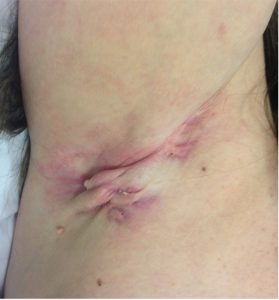

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a recurring, chronic, and inflammatory condition that affects skin predominantly in apocrine glands bearing areas, although the primary defect is in the hair follicle. The early primary lesions are solitary, painful, round nodules that may remain unchanged for weeks or months with occasional inflammation. In most severe cases, the nodules evolve to become abscesses and may burst spontaneously or after excision. The secondary lesions lead to the formation of tunnels or sinus tracts and release of serous, purulent, or blood-stained discharge with a foul odour. In some cases, ulcerations can occur. A characteristic feature of secondary lesions is hypertrophic scars which may appear as indurate plaques or linear rope like bands (Figure 1).

HS usually presents after puberty with a global prevalence of 1% in the general population. There is often a family history of HS and its associated diseases (severe acne, arthritis, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, metabolic syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease). In Danish young women, a peak prevalence of 4% has been reported. The causes of hidradenitis suppurativa are unknown, however risk factors including tobacco use, genetics, infections, immunity, and obesity have been hypothesized. HS is a genetically heterogenous disease with several different mutations. Furthermore, although bacteria are heavily involved in the clinical manifestation of HS, the micro-organisms do not play a causative role but secondary infections do occur. There also appears to be some hormonal factors associated with the disease. Specifically, the higher frequency in females, improvement of symptoms during pregnancy, and disease resolution after menopause indicate the importance of hormonal factors in HS. A study of immunological indicators also suggests that HS may be an auto-inflammatory disease, however, more investigation in this area is needed.

To diagnose HS, three criteria must be met. Firstly, the typical lesions described above must be present. Secondly, the lesions must be present in the typical bodily areas (not always all regions) including perineal and perianal region, axillae, groin, buttocks, infra- and inter-mammary folds more commonly in females. Lastly, the lesions must be chronic and recurrent (at least 2 flares in 6 months).

The treatment is based on severity of the disease, patient’s goals and the frequency of symptom exacerbation. Smoking sensation and weight loss are often beneficial in decreasing the frequency and severity of acute episodes. HS patients benefit from interprofessional disciplinary care with evaluation of associated comorbidities and risk factors. The management of HS is a combined medical and surgical therapies. The goal of medical therapy is to control the existing inflammation, prevention of flare and new lesions. The surgical management helps removal of irreversible tissue damage, the removal of biofilms inside the tunnels and tracts as the continuous trigger of inflammatory process. For patients with recurrent painful nodules with periods of remissions, treatments like antiseptics, keratolytics, antibiotics, intralesional steroids, are used to prevent primary lesions from evolving into abscesses. For management of moderate to sever HS, antibiotics, antiandrogens, and anti-TNF drugs along with appropriate surgical procedure are suggested. (Revuz, 2009).

Pyoderma Gangrenosum

Pyoderma Gangrenosum (PG) is a painful ulcerative condition and the worldwide incidence of PG is estimated to be 3 to 10 cases per million population per year (Monari et al., 2018). It usually presents between ages 20 to 50 years with up to 75% of PG being reported in association with a systemic disease including inflammatory arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, and lymphoproliferative disorders. The aetiology of PG is still unknown, however, its frequent association with systemic disorders links PG to a probable underlying immunologic abnormality. Specifically, neutrophil dysfunction and interleukin-8 overexpression has been observed in some PG patients. The Pathergy phenomenon sometimes observed at the onset of PG further strengthens this hypothesis about immune disturbances.

The characteristic feature of PG is an ulcer with a raised, dusky red or purple inflammatory border and a necrotic base (Figure 2).

Primary eruptions are most common on the legs presenting as either solitary or multiple lesions. These begin as either a deep-seated painful nodule or a superficial hemorrhagic pustule, sometimes after a minor trauma (pathergy). The central ulceration occurs due to necrosis and releases a purulent and hemorrhagic exudate. The ulcer expands in one or more directions in a serpiginous (snake-like) pattern with an intense halo of bright erythema surrounding the margins (elevated rolled border). This expansion is a result of the burrowing extension of the undermined margin or from new hemorrhagic pustules in the borders. There can be one or more ulcers, and, in some cases, multiple ulcers combine to become multicentric, irregular ulcerations. PG has multiple morphological types with ulcerative (the most common), pustular (associated with inflammatory bowel disease – IBD), bullous associated with malignancy (especially acute myelogenous leukemia – AML) and vegetative (rare and with no association). In addition, 3 other ulcerative types of PG are reported: post-surgical PG, peristomal PG and drug induced PG.

PG ulcers lose their typical characteristics by time and by partial treatment and may mimic any ulcers. The diagnosis of PG involves firstly ruling out other differential diagnoses and then, determining the presence of a treatable underlying systemic disorder. Often, procedures including blood work, biopsies for histopathology and culture, radiographic studies, flexible sigmoidoscopy, and colonoscopy are performed to rule other diagnoses based on the presenting clinical clues. Biopsy should have a predominant neutrophilic infiltrate for diagnosis as the only major criteria along with characteristic clinical features (Maverakis et al. 2018).

For ulcerative PG, the clinical presentation may include*:

- The need to rule out infection

- At least one lesion or multiple lesions on the legs

- Starts with small pustules, papules or vesicles and rapidly evolves

- Characteristic cribriform scarring (wrinkled paper-like)

- Responds to immunosuppressant therapy within a month (decrease in ulcer size)

*Modified from Maverakis et al. 2018

There is no single therapy that works for all PG patients. Instead, the treatment depends on lesion depth and rapidity of the expansion, the associated disorder, baseline patient status, and treatment tolerance. Wound management is critical in PG to improve healing. Cases with limited involvement can be treated with topical and intralesional treatments. More extensive and progressive lesions require systemic therapies. Corticosteroids the main stay of treatment but may have adverse events long term. The rapid acting agents including systemic corticosteroids or cyclosporine are often needed to control disease activity and the presence of new lesions. Other immunosuppressive agents including biologics (tumour necrosis factor – TNF inhibitors) can be used for long-term prevention of recurrences. Treatment of associated systemic disorders like inflammatory bowel disease is important but the activity of these diseases is not always directly linked to PG (Ruocco et al., 2009).

Vasculitis

Vasculitis is defined as the destruction of blood vessel walls due to inflammatory cell infiltration. Cutaneous vasculitis (CV), specifically, manifests most commonly on the lower legs as ulcers, purpura, purpuric papules, infarcts, infiltrating erythema (redness), urticaria (hives), livedo reticularis (net-like vasculature), nodules and digital gangrenes. Palpable purpura is the hallmark of cutaneous vasculitis and can be felt with your examining fingers and eyes closed.

The disease can progress in three ways:

• a single acute episode resolved within six months or less

• episodic relapses of showers of palpable purpura with symptom free periods

• a chronic disease with no remission.

The type of skin lesions depends on the size of the affected blood vessels. Small superficial vessel damage leads to purpuric papules and infiltrated erythema. Medium sized vessels at the dermal – epidermal junction results in the presence of nodules (elevated lesions with depth). Larger vessels in the subcutaneous fat are more likely on the proximal thighs and are more likely to ulcerate (loss of epidermis with a dermal or deeper base) (Figure 3).

Vasculitis damage to medium sized muscular arteries can result in nodules, ulcers, pitted scars and livedo reticularis depending on the extent of injury. Cutaneous vasculitis may be associated with internal organ damage. Commonly, the joints, liver and kidneys may be involved and less likely, the heart, lungs, GI tract and brain. Lastly, large vessel damage can lead to more serious symptoms including limb claudication.

The etiologic association of CV include 40% idiopathic cases (unknown cause), 20% adverse drug reactions, 22% related to infections, 12% associated with connective tissue disease, 10% related to IgA related small vessel vasculitis of the skin that can also affect the kidneys (previously known as Henoch Schonlein purpura) and less than 5% with malignancies. The annual incidence of biopsy proven CV is estimated to be 39.6-59.8 per million general population. Although it affects individuals from all ages, it is more prevalent in adult women with a mean age at onset of 47 years.

To diagnose CV, skin biopsy for routine light microscopy and direct immunofluorescent findings (around blood vessels with immunoglobulins or C3 complement) is performed to detect the disease and rule out other illnesses. To further support the diagnosis of CV, clinical history, physical and lab findings, along with angiographic assessment in selected patients may be needed. Specifically, information like affected vessel size, and the presence and type of internal organ involvement can assist in a specific diagnosis. Specialized tests are recommended including hepatitis B and C, comprehensive blood chemistry, complete blood count, urine analysis and chest radiographs. Consider HIV testing in selected patients. With chronic or recurrent disease, other immune tests including ANCA (antineutrophilic cytoplasmic antibodies), ANA (antinuclear antibodies) and ENA (extractable nuclear antigen includes Ro/SS-A antibody) and complement levels may be required. Selected patients may require urine toxicology for cocaine / levamisole, ECHO cardiography, visceral angiography and malignancy screening.

Furthermore, if CV is present, it is important to look for any treatable causes including infection, systemic disease, and drug adverse effects since etiology often dictates disease evolution. Treatment is dictated by disease severity. For short lived single episodes, measures like leg elevation, avoiding cold exposure and tight-fitting clothes, antihistamines, and anti-inflammatory agents are recommended. For persistent and recurrent disease with burning and itching sensations, dapsone and colchicine are commonly ordered. For moderate to severe disease with extensive persistent symptoms like ulcers and nodules, prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate are recommended. If there is risk of permanent damage or death, more aggressive treatment including high-dose prednisone combined with cyclophosphamide or azathioprine are used. For treatment resistant disease with a specific underlying condition, novel therapies including TNF inhibitors are recommended (Carlson et al., 2006).

Authors:

Authors: Muskaan Sachdeva (BHSc)1, Afsaneh Alavi (MD, FRCPC)1,2

1Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada

2Department of Dermatology, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Corresponding Author:

Afsaneh Alavi, MD, FRCPC

Department of Dermatology

Mayo Clinic , Rochester, MN

55905, United states

Email: alavi.afsaneh@mayo.edu

Figures: 2

Conflicts of interest:

Dr. Alavi received honoraria from AbbVie, Arcutis, BMS Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bausch Celgene, Dermira, Dermovant, DSBiopharma, Eli Lilly, EMD Serono, Galderma, Glenmark, GSK, Incyte, Ilkos, Janssen, LEO Pharma, Kyowa Kirin, Kymera, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, Sanofi Aventis, UCB,Valeant, Xenon, and Xoma.

Ms. Sachdeva has no conflicts of interest to disclose.