5.2 (A)‘Internalizing’ an Externality: Pollution Tax

Now we know that an externality is a form of market failure that arises because market participants do not account for factors external to the market. This makes the market quantity is too low or too high relative to the socially optimal level of production. In Chapters 3 and 4, we learned a variety of policies that influence the number of goods exchanged in a market. We can use these to set quantity where D = S. If we create a policy correctly, we can bring the market back to the social surplus maximizing level of output.

We can either set the appropriate quantity directly through a price floor or price ceiling. More commonly, governments address the externality through a tax or subsidy. In this case, the government introduces a tax that will make market participants act as if they care about participants outside the market. In economic jargon, this is called internalizing the externality. A tax that addresses a negative externality by taxing the good instead of the actual external cost is called a Pigouvian tax.

Example

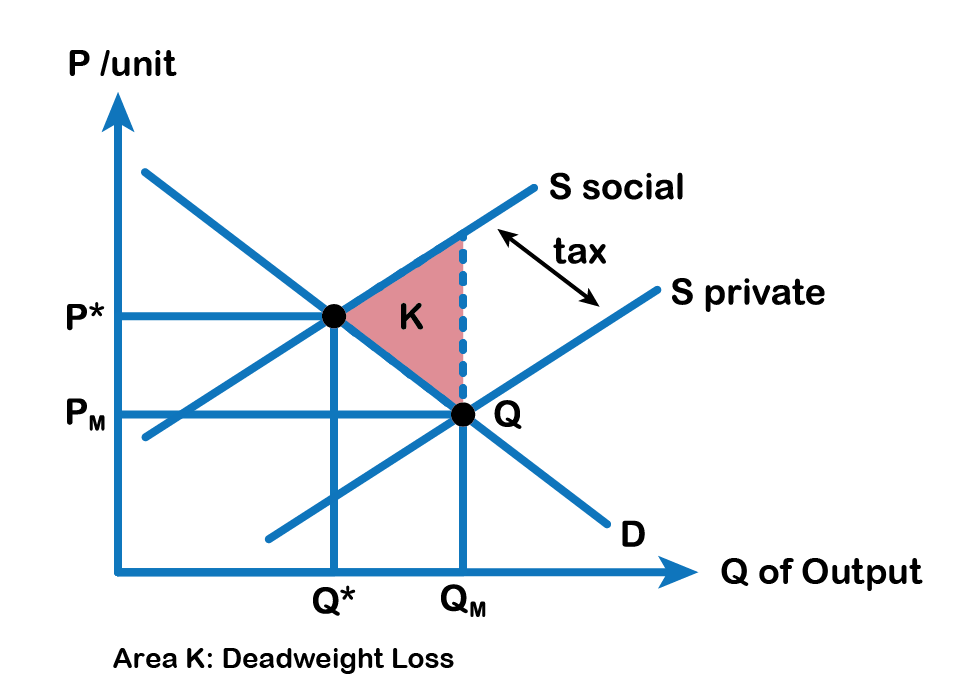

Consider the following figure of a market with a negative externality present

We know that without regulation, the market will naturally tend to QM (where D-private = S-private) and that this will result in a deadweight loss of area K. Ideally, we want the quantity exchanged to equal Q*, which is the social surplus optimizing the level of production since this level of output is where D-private = S-social. How can we force the market here? One way is to introduce a tax equal to the marginal external cost at the efficient quantity Q*. This makes the producer face a cost curve of S-private + tax, = S-social and since the tax is equal to external costs, this will just cause firms to act as though they recognize the externality.

A common misconception is that introducing a tax in this market eliminates external costs. This is incorrect. In some sense, we are aiming for an “optimal” level of external cost. To get a sense of this, consider the manufacturing industry. We could get external costs (like the adverse effects of carbon dioxide emissions) to equal zero if we stopped production entirely, but then we would have a world with little energy.

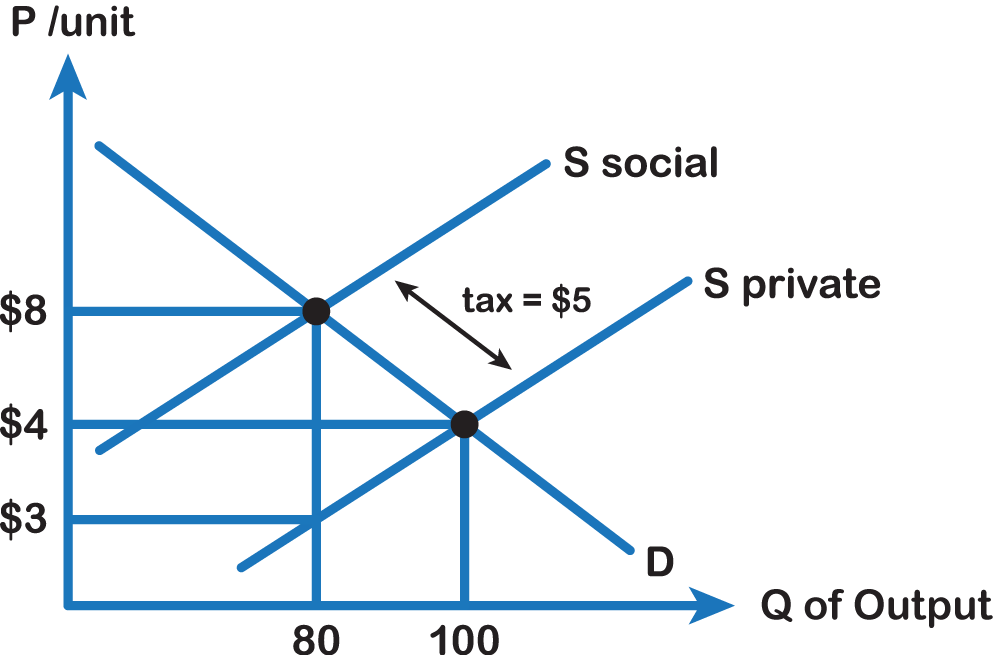

In the above graph, the equilibrium quantity is 100 and the socially efficient level of output is 80. The intuition behind the policy response is the same as before, but we have to be careful about the amount of the tax as the marginal external cost is changing. We want to set the level of the tax equal to the marginal external cost at the socially efficient level of output. This value is 8 minus 3 or $5. We know that setting a tax equal to $5 will bring us to 80 units, where social welfare is maximized.

Attribution

“5.2 Indirectly Correcting Externalities” in Principles of Microeconomics by Dr. Emma Hutchinson, University of Victoria is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.