3.7 – Changes in Equilibrium Price and Quantity: The Four-Step Process

Learning Objectives

- Identify equilibrium price and quantity through the four-step process

- Graph equilibrium price and quantity

- Contrast shifts of demand or supply and movements along a demand or supply curve

- Graph demand and supply curves, including equilibrium price and quantity, based on real-world examples

Let’s begin this discussion with a single economic event. It might be an event that affects demand, like a change in income, population, tastes, prices of substitutes or complements, or expectations about future prices. It might be an event that affects supply, like a change in natural conditions, input prices, or technology, or government policies that affect production. How does this economic event affect equilibrium price and quantity? We will analyze this question using a four-step process.

Step 1. Draw a demand and supply model before the economic change took place. To establish the model requires four standard pieces of information: The law of demand, which tells us the slope of the demand curve; the law of supply, which gives us the slope of the supply curve; the shift variables for demand; and the shift variables for supply. From this model, find the initial equilibrium values for price and quantity.

Step 2. Decide whether the economic change you are analyzing affects demand or supply. In other words, does the event refer to something in the list of demand factors or supply factors?

Step 3. Decide whether the effect on demand or supply causes the curve to shift to the right or to the left, and sketch the new demand or supply curve on the diagram. In other words, does the event increase or decrease the amount consumers want to buy or producers want to sell?

Step 4. Identify the new equilibrium and then compare the original equilibrium price and quantity to the new equilibrium price and quantity.

Let’s consider one example that involves a shift in supply and one that involves a shift in demand. Then we will consider an example where both supply and demand shift.

Good Weather for Salmon Fishing

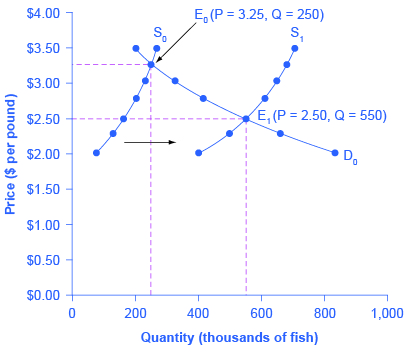

Supposed that during the summer of 2015, weather conditions were excellent for commercial salmon fishing off the California coast. Heavy rains meant higher than normal levels of water in the rivers, which helps the salmon to breed. Slightly cooler ocean temperatures stimulated the growth of plankton, the microscopic organisms at the bottom of the ocean food chain, providing everything in the ocean with a hearty food supply. The ocean stayed calm during fishing season, so commercial fishing operations did not lose many days to bad weather. How did these climate conditions affect the quantity and price of salmon? Figure 3.7a illustrates the four-step approach, which we explain below, to work through this problem. Table 3.7a also provides the information to work the problem.

Figure 3.7a Good Weather for Salmon Fishing: The Four-Step Process (Text Version)

The graph represents the four-step approach to determining shifts in the new equilibrium price and quantity in response to good weather for salmon fishing.

The vertical axis is Price ($ Per Pound) ranging from $0 to $4 increasing by $0.50 increments and the horizontal axis is Quantity (thousands of fish) increasing by increments of 200.

The original supply curve (S0) is slightly bowed curve sloping upwards from left to right. The new supply curve (S1) shifts to the right and is a convex curve sloping upwards from left to right.

Point E0 occurs along S0 at ($3.25 per pound, 250 thousand fish) and E1 occurs along the S1 at ($2.50 per pound, 550 thousand fish). The demand curve (D0) slopes downward left to right intersecting both E0 and E1.

The original supply curve uses data points from Quantity Supplied in 2014, the new supply curve uses data points from Quantity Supplied in 2015, and the demand curve (D0) uses data points from Quantity demand.

| Price per Pound ($) | Quantity Supplied in 2014 | Quantity Supplied in 2015 | Quantity Demanded |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2.00 | 80 | 400 | 840 |

| 2.25 | 120 | 480 | 680 |

| 2.50 | 160 | 550 | 550 |

| 2.75 | 200 | 600 | 450 |

| 3.00 | 230 | 640 | 350 |

| 3.25 | 250 | 670 | 250 |

| 3.50 | 270 | 700 | 200 |

Step 1. Draw a demand and supply model to illustrate the market for salmon in the year before the good weather conditions began. The demand curve D0 and the supply curve S0 show that the original equilibrium price is $3.25 per pound and the original equilibrium quantity is 250,000 fish. (This price per pound is what commercial buyers pay at the fishing docks. What consumers pay at the grocery is higher.)

Step 2. Did the economic event affect supply or demand? Good weather is an example of a natural condition that affects supply.

Step 3. Was the effect on supply an increase or a decrease? Good weather is a change in natural conditions that increases the quantity supplied at any given price. The supply curve shifts to the right, moving from the original supply curve S0 to the new supply curve S1, which Figure 3.7a and Table 3.7a show.

Step 4. Compare the new equilibrium price and quantity to the original equilibrium. At the new equilibrium E1, the equilibrium price falls from $3.25 to $2.50, but the equilibrium quantity increases from 250,000 to 550,000 salmon. Notice that the equilibrium quantity demanded increased, even though the demand curve did not move.

In short, good weather conditions increased supply of the California commercial salmon. The result was a higher equilibrium quantity of salmon bought and sold in the market at a lower price.

Newspapers and the Internet

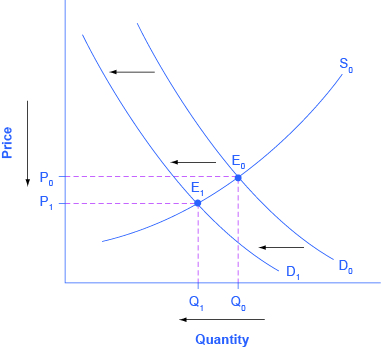

According to the Pew Research Center for People and the Press, increasingly more people, especially younger people, are obtaining their news from online and digital sources. The majority of U.S. adults now own smartphones or tablets, and most of those Americans say they use them in part to access the news. From 2004 to 2012, the share of Americans who reported obtaining their news from digital sources increased from 24% to 39%. How has this affected consumption of print news media, and radio and television news? Figure 3.7b and the text below illustrates using the four-step analysis to answer this question.

Figure 3.7b The Print News Market: A Four-Step Analysis (Text Version)

The vertical axis is Price and has a downward facing arrow next to it showing an increase in price. The horizontal axis is Quantity and it has an arrow facing left to show a decrease in quantity. The supply curve (S0) is concave and slopes upward left to right. The original demand curve (D0) is concave and slopes upward from right to left and intersects the centre of S0 at Point E0 (Q0, P0). Arrows pointing from right to left between D0 and D2 show the shift in demand curve. The original demand curve (D0) shifts to the left to the new demand curve (D1). D1 now intersects with S0 at E2 at point (Q2, P2) with P0 shifting downward to P2 and Q0 shifting to the left from Q0 to Q2.

Step 1. Develop a demand and supply model to think about what the market looked like before the event. Price is on the vertical axis and quantity is on the horizontal axis. The original quanity is Q0 and the original price is P0. The demand curve D0 and the supply curve S0 shows the original relationships. In this case, we perform the analysis without specific numbers on the price and quantity axis. The supply curve S0 is concave trending upward from left to right. The demand curve D0 is concave trending downward from left to right and intersects with the supply curve at E0 equilibrium price occuring at (Q0, P0).

Step 2. Did the described change affect supply or demand? A change in tastes, from traditional news sources (print, radio, and television) to digital sources, caused a change in demand for the former.

Step 3. Was the effect on demand positive or negative? A shift to digital news sources will tend to mean a lower quantity demanded of traditional news sources at every given price, causing the demand curve for print and other traditional news sources to shift to the left, from D0 to D1. The supply curve S0 remains the same. Quanity is lower, shifting left to Q1, and price is also lower shifting downward to P1 and is at the point where the new demand curve D1 instersects with supply curve S0 equilibrium price is now E1.

Step 4. Compare the new equilibrium price and quantity (E1) to the original equilibrium price (E0). The new equilibrium (E1) occurs at a lower quantity and a lower price than the original equilibrium (E0).

The decline in print news reading predates 2004. Print newspaper circulation peaked in 1973 and has declined since then due to competition from television and radio news. In 1991, 55% of Americans indicated they received their news from print sources, while only 29% did so in 2012. Radio news has followed a similar path in recent decades, with the share of Americans obtaining their news from radio declining from 54% in 1991 to 33% in 2012. Television news has held its own over the last 15 years, with a market share staying in the mid to upper fifties. What does this suggest for the future, given that two-thirds of Americans under 30 years old say they do not obtain their news from television at all?

The Interconnections and Speed of Adjustment in Real Markets

In the real world, many factors that affect demand and supply can change all at once. For example, the demand for cars might increase because of rising incomes and population, and it might decrease because of rising gasoline prices (a complementary good). Likewise, the supply of cars might increase because of innovative new technologies that reduce the cost of car production, and it might decrease as a result of new government regulations requiring the installation of costly pollution-control technology.

Moreover, rising incomes and population or changes in gasoline prices will affect many markets, not just cars. How can an economist sort out all these interconnected events? The answer lies in the ceteris paribus assumption. Look at how each economic event affects each market, one event at a time, holding all else constant. Then combine the analyses to see the net effect.

A Combined Example

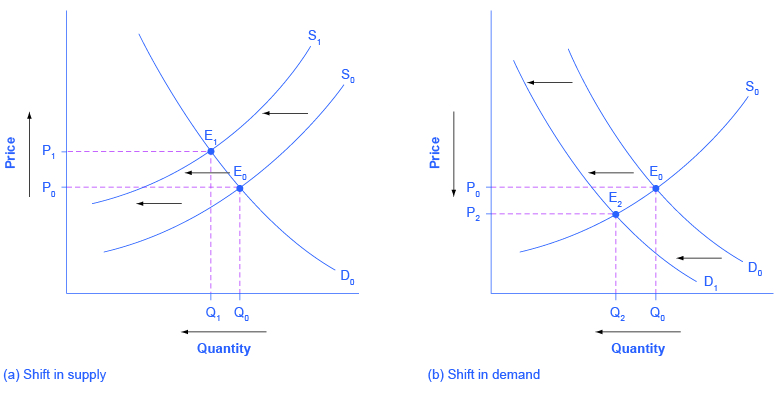

The U.S. Postal Service is facing difficult challenges. Compensation for postal workers tends to increase most years due to cost-of-living increases. At the same time, increasingly more people are using email, text, and other digital message forms such as Facebook and Twitter to communicate with friends and others. What does this suggest about the continued viability of the Postal Service? Figure 3.7c and the text below illustrate this using the four-step analysis to answer this question.

Figure 3.7c Higher Compensation for Postal Workers: A Four-Step Analysis (Text Version)

There are two graphs: Graph A depicts the shift in supply and Graph B depicts the shift in demand.

Graph A: The vertical axis is Price and has an upward facing arrow next to it showing an increase in price. The horizontal axis is Quantity and it has an arrow facing left to show a decrease in quantity. The original supply curve (S0) is concave and slopes upward left to right. Point E0 (Q0, P0) occurs along S0. The new supply curve (S1) shifts to the left running parallel toS0. Occurring along S1, Point E1 occurs at (Q1, P1) quantity has shifted left from Q0 to Q1 and P0. Arrows pointing from right to left between S0 and S1 show the shift in supply curve. The demand curve (D0) is concave and slopes upward from right to left and intersects the centre of both supply curves S0 and S1.

Graph B: The vertical axis is Price and has a downward facing arrow next to it showing an decrease in price. The horizontal axis is Quantity and it has an arrow facing left to show a decrease in quantity. The supply curve (S0) is concave and slopes upward left to right. The original demand curve (D0) is concave and slopes upward from right to left and intersects the centre of S0 at Point E0 (Q0, P0). Arrows pointing from right to left between D0 and D2 show the shift in demand curve. The original demand curve (D0) shifts to the left to the new demand curve (D1). D1 now intersects with S0 at E2 at point (Q2, P2) with P0 shifting downward to P2 and Q0 shifting to the left from Q0 to Q2.

Figure 3.7c Higher Compensation for Postal Workers: A Four-Step Analysis (a) Higher labour compensation causes a leftward shift in the supply curve, a decrease in the equilibrium quantity, and an increase in the equilibrium price. (b) A change in tastes away from Postal Services causes a leftward shift in the demand curve, a decrease in the equilibrium quantity, and a decrease in the equilibrium price.

Since this problem involves two disturbances, we need two four-step analyses, the first to analyze the effects of higher compensation for postal workers, the second to analyze the effects of many people switching from “snail mail” to email and other digital messages.

Figure 3.7c (a) shows the shift in supply discussed in the following steps.

Step 1. Draw a demand and supply model to illustrate what the market for the U.S. Postal Service looked like before this scenario starts. The demand curve D0 and the supply curve S0 show the original relationships.

Step 2. Did the described change affect supply or demand? Labour compensation is a cost of production. A change in production costs caused a change in supply for the Postal Service.

Step 3. Was the effect on supply positive or negative? Higher labour compensation leads to a lower quantity supplied of postal services at every given price, causing the supply curve for postal services to shift to the left, from S0 to S1.

Step 4. Compare the new equilibrium price and quantity to the original equilibrium price. The new equilibrium (E1) occurs at a lower quantity and a higher price than the original equilibrium (E0).

Figure 3.7c (b) shows the shift in demand in the following steps.

Step 1. Draw a demand and supply model to illustrate what the market for U.S. Postal Services looked like before this scenario starts. The demand curve D0 and the supply curve S0 show the original relationships. Note that this diagram is independent from the diagram in panel (a).

Step 2. Did the change described affect supply or demand? A change in tastes away from snail mail toward digital messages will cause a change in demand for the Postal Service.

Step 3. Was the effect on demand positive or negative? A change in tastes away from snailmail toward digital messages causes lower quantity demanded of postal services at every given price, causing the demand curve for postal services to shift to the left, from D0 to D1.

Step 4. Compare the new equilibrium price and quantity to the original equilibrium price. The new equilibrium (E2) occurs at a lower quantity and a lower price than the original equilibrium (E0).

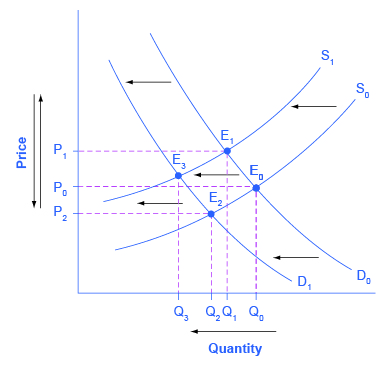

The final step in a scenario where both supply and demand shift is to combine the two individual analyses to determine what happens to the equilibrium quantity and price. Graphically, we superimpose the previous two diagrams one on top of the other, as in Figure 3.7d.

Figure 3.7d Combined Effect of Decreased Demand and Decreased Supply (Text Version)

The vertical axis is Price and the horizontal axis is Quantity. The original supply curve (S0) slopes upward from left to right. The original demand curve (D0) slopes downward from left to right.

Where the original supply curve (S0) and original demand curve (D0) intersects is the original equilibrium at point P0 Q0.

Effect on Quantity: The effect of higher labour compensation on Postal Services because it raises the cost of production is to decrease the equilibrium quantity. Both the demand and supply curve shift: D0 shifts to the left to D1 and S0 shifts to the left to S1. The decrease in the equilibrium quantity of Postal Services (Q3) results in a new equilibrium (E3), which occurs where S1 and D1 intersect.

Effect on Price: There are different factors that can affect the price equilibrium:

The effect of higher labour compensation on Postal Services, because it raises the cost of production, is to increase the equilibrium price. Quantity decreases and S0 shifts to the left to Q1; however, D0 remains the same. S1 and D0 intersect at the new equilibrium E1 at P1, Q1.

The effect of a change in tastes away from snail mail is to decrease the equilibrium price. Quantity decreases and D0 shifts to the left to Q2; however, S0 remains the same. D1 and S0 intersect at the new equilibrium E2 at P2, Q2.

Following are the results:

Effect on Quantity: The effect of higher labour compensation on Postal Services because it raises the cost of production is to decrease the equilibrium quantity. The effect of a change in tastes away from snail mail is to decrease the equilibrium quantity. Since both shifts are to the left, the overall impact is a decrease in the equilibrium quantity of Postal Services (Q3). This is easy to see graphically, since Q3 is to the left of Q0.

Effect on Price: The overall effect on price is more complicated. The effect of higher labour compensation on Postal Services, because it raises the cost of production, is to increase the equilibrium price. The effect of a change in tastes away from snail mail is to decrease the equilibrium price. Since the two effects are in opposite directions, unless we know the magnitudes of the two effects, the overall effect is unclear. This is not unusual. When both curves shift, typically we can determine the overall effect on price or on quantity, but not on both. In this case, we determined the overall effect on the equilibrium quantity, but not on the equilibrium price. In other cases, it might be the opposite.

The next Clear It Up feature focuses on the difference between shifts of supply or demand and movements along a curve.

Clear It Up

What is the difference between shifts of demand or supply versus movements along a demand or supply curve?

One common mistake in applying the demand and supply framework is to confuse the shift of a demand or a supply curve with movement along a demand or supply curve. As an example, consider a problem that asks whether a drought will increase or decrease the equilibrium quantity and equilibrium price of wheat. Lee, a student in an introductory economics class, might reason:

“Well, it is clear that a drought reduces supply, so I will shift back the supply curve, as in the shift from the original supply curve S0 to S1 on the diagram (Shift 1). The equilibrium moves from E0 to E1, the equilibrium quantity is lower and the equilibrium price is higher. Then, a higher price makes farmers more likely to supply the good, so the supply curve shifts right, as shows the shift from S1 to S2, shows on the diagram (Shift 2), so that the equilibrium now moves from E1 to E2. The higher price, however, also reduces demand and so causes demand to shift back, like the shift from the original demand curve, D0 to D1 on the diagram (labeled Shift 3), and the equilibrium moves from E2 to E3.”

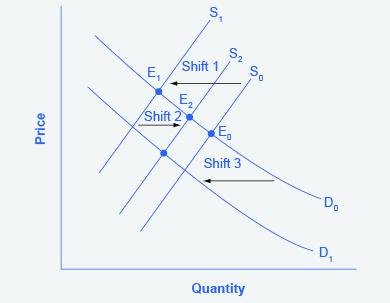

Figure 3.7e Shifts of Demand or Supply versus Movements along a Demand or Supply Curve (Text Version)

The vertical axis is Price and the horizontal axis is Quantity. The original supply curve (S0) is linear sloping upwards from left to right in the middle of the graph. The original demand curve (D0) is slightly curved sloping downward from left to right and intersects with S0 at Point E0, the original equilibrium.

Shift 1: S0 shifts furthest to the left to S1; E0 also shifts to the left where S1 and D0 intersect, denoted by Point E1.

Shift 2: S1 then shifts slightly back to the right becoming S2; E1 also shifts to the right to where S2 and D0 intersect, denoted by Point E2.

Shift 3: D0 shifts to D1 shifts to the left; E2 shifts downward to a new point of equilibrium at S2 and D1.

At about this point, Lee suspects that this answer is headed down the wrong path. Think about what might be wrong with Lee’s logic, and then read the answer that follows.

Answer: Lee’s first step is correct: that is, a drought shifts back the supply curve of wheat and leads to a prediction of a lower equilibrium quantity and a higher equilibrium price. This corresponds to a movement along the original demand curve (D0), from E0 to E1. The rest of Lee’s argument is wrong, because it mixes up shifts in supply with quantity supplied, and shifts in demand with quantity demanded. A higher or lower price never shifts the supply curve, as suggested by the shift in supply from S1 to S2. Instead, a price change leads to a movement along a given supply curve. Similarly, a higher or lower price never shifts a demand curve, as suggested in the shift from D0 to D1. Instead, a price change leads to a movement along a given demand curve. Remember, a change in the price of a good never causes the demand or supply curve for that good to shift.

Think carefully about the timeline of events: What happens first, what happens next? What is cause, what is effect? If you keep the order right, you are more likely to get the analysis correct.

In the four-step analysis of how economic events affect equilibrium price and quantity, the movement from the old to the new equilibrium seems immediate. As a practical matter, however, prices and quantities often do not zoom straight to equilibrium. More realistically, when an economic event causes demand or supply to shift, prices and quantities set off in the general direction of equilibrium. Even as they are moving toward one new equilibrium, a subsequent change in demand or supply often pushes prices toward another equilibrium.

Key Concepts and Summary

When using the supply and demand framework to think about how an event will affect the equilibrium price and quantity, proceed through four steps:

- sketch a supply and demand diagram to think about what the market looked like before the event

- decide whether the event will affect supply or demand

- decide whether the effect on supply or demand is negative or positive, and draw the appropriate shifted supply or demand curve

- compare the new equilibrium price and quantity to the original ones.

Attribution

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from "Changes in Equilibrium Price and Quantity: The Four-Step Process" and "Key Concepts and Summary" In Principles of Economics 2e (OpenStax) by Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro, licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Access for free at Principles of Microeconomics 2e

Original Source Chapter References

Costanza, Robert, and Lisa Wainger. “No Accounting For Nature: How Conventional Economics Distorts the Value of Things.” The Washington Post. September 2, 1990.

European Commission: Agriculture and Rural Development. 2013. "Overview of the CAP Reform: 2014-2024." Accessed April 13, 205. http://ec.europa.eu/agriculture/cap-post-2013/.

Radford, R. A. “The Economic Organisation of a P.O.W. Camp.” Economica. no. 48 (1945): 189-201. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2550133.

Landsburg, Steven E. The Armchair Economist: Economics and Everyday Life. New York: The Free Press. 2012. specifically Section IV: How Markets Work.

National Chicken Council. 2015. "Per Capita Consumption of Poultry and Livestock, 1965 to Estimated 2015, in Pounds." Accessed April 13, 2015. https://www.nationalchickencouncil.org/about-the-industry/statistics/per-capita-consumption-of-poultry-and-livestock-1965-to-estimated-2012-in-pounds/.

Wessel, David. “Saudi Arabia Fears $40-a-Barrel Oil, Too.” The Wall Street Journal. May 27, 2004, p. 42. https://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB108561000087822300.

Pew Research Center. “Pew Research: Center for the People & the Press.” http://www.people-press.org/.

Media Attributions

- Figure 3.16 Good Weather for Salmon Fishing: The Four-Step Process © Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro (OpenStax) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 3.17 The Print News Market: A Four-Step Analysis © Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro (OpenStax) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 3.18 Higher Compensation for Postal Workers: A Four-Step Analysis © Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro (OpenStax) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 3.19 Combined Effect of Decreased Demand and Decreased Supply © Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro (OpenStax) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- Figure 3.20 Shifts of Demand or Supply versus Movements along a Demand or Supply Curve © Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro (OpenStax) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license