7.5 Global Innovation

Many companies now have global supply chains and product development processes, but few have developed effective global innovation capabilities (Santos et al., 2004). Increasingly, however, technology access and innovation are becoming key global strategic drivers. This move from cost to growth and innovation is likely to continue as the centre of gravity of economic activity shifts further to the East.

A core competency in global innovation—the ability to leverage new ideas all around the world—has become a major source of global competitive advantage, as companies such as Nokia, Airbus, SAP, and Starbucks demonstrate. They realize that the principal constraint on innovation “performance” is knowledge. Accessing a diverse set of sources of knowledge is, therefore, a key challenge and is critical to successful differentiation. Companies whose knowledge pool is the same as that of its competitors will likely develop uninspired “me, too” products; access to a diversity of knowledge allows a company to move beyond incremental innovation to attention-grabbing designs and breakthrough solutions.

There is an interesting relationship between geography and knowledge diversity. In Finland, for example, the high cost of installing and maintaining fixed telephone lines in isolated places has spurred advances in radio telephony. In Germany, cultural and political factors have encouraged the growth of a strong “green movement,” which in turn has generated a distinctive market and technical knowledge in recycling and renewable energy. Just-in-time production systems were pioneered in part because of high land costs there. Recognition of the role played by geography in innovation has prompted many companies to globalize their perspective on the innovation process. For example, pharmaceutical companies such as Novartis AG and GlaxoSmithKline plc now realize that the knowledge they need extends far beyond traditional chemistry and therapeutics to include biotechnology and genetics. What is more, much of this new knowledge comes from sources other than the companies’ traditional R&D labs in Basel, Bristol, and in New Jersey, from places such as California, Tel Aviv, Cuba, or Singapore. For these companies, globalization of innovation processes is no longer optional—it has become imperative.

Companies that globalize their supply chains by accessing raw materials, components, or services from around the world are typically able to reduce the overall costs of their operations. Similarly, a side benefit of global innovation is cost reduction. Consider, for example, how companies are now leveraging software programmers in Bangalore, India, aerospace technologists in Russia, or chipset designers in China to cut the costs of their innovation processes.

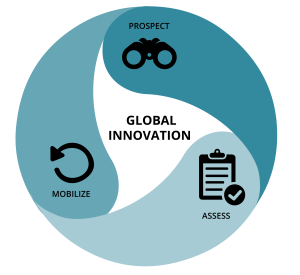

To reap the benefits of global innovation, companies must do three things:

- Prospect (find the relevant pockets of knowledge from around the world)

- Assess (decide on the optimal “footprint” for a particular innovation)

- Mobilize (use cost-effective mechanisms to move distant knowledge without degrading (Santos et al., 2004).

Prospecting—that is, finding valuable new pockets of knowledge to spur innovation—may well be the most challenging task. The process involves knowing what to look for, where to look for it, and how to tap into a promising source. Santos et al. (2004) cite the efforts of the cosmetics maker Shiseido Co., Ltd., in entering the market for fragrance products. Based in Japan, a country with a very limited tradition of perfume use, Shiseido was initially unsure of the precise knowledge it needed to enter the fragrance business. But the company did know where to look for it. So it bought two exclusive beauty boutique chains in Paris, mainly as a way to experience, firsthand, the personal care demands of the most sophisticated customers of such products. It also hired the marketing manager of Yves Saint Laurent Parfums and built a plant in Gien, a town located in the French perfume “cluster.” France’s leadership in that industry made the where fairly obvious to Shiseido. The how had also become painfully clear because the company had previously flopped in its efforts to develop perfumes in Japan. Those failures convinced Shiseido executives that to access such complex knowledge—deeply rooted in local culture and combining customer information, aesthetics, and technology—the company had to immerse itself in the French environment and learn by doing. Having figured out the where and how, Shiseido would gradually learn what knowledge it needed to succeed in the perfume business.

Assessing new sources of innovation, that is, incorporating new knowledge into and optimizing an existing innovation network, is the second important challenge companies face. If a semiconductor manufacturer is developing a new chipset for mobile phones, for example, should it access technical and market knowledge from Silicon Valley, Austin, Hinschu, Seoul, Bangalore, Haifa, Helsinki, and Grenoble? Or should it restrict itself to just some of those sites? At first glance, determining the best footprint for innovation does not seem fundamentally different from the trade-offs companies face in optimizing their global supply chains: adding a new source might reduce the price or improve the quality of a required component, but more locations may also mean additional complexity and cost. Similarly, every time a company adds a source of knowledge to the innovation process, it might improve its chances of developing a novel product, but it also increases costs. Determining an optimal innovation footprint is more complicated, however, because the direct and indirect cost relationships are far more imprecise.

Mobilizing the footprint, that is, integrating knowledge from different sources into a virtual melting pot from which new products or technologies can emerge, is the third challenge. To accomplish this, companies must bring the various pieces of (technical) knowledge that are scattered around the world together and provide a suitable organizational form for innovation efforts to flourish. More importantly, they would have to add the more complex, contextual (market) knowledge to integrate the different pieces into an overall innovation blueprint.

Case: P&G’s Success in Trickle-Up Innovation: Vicks Cough Syrup With Honey

A new over-the-counter medicine from Vicks that has recently become popular in Switzerland is not as new as it seems. The product, Vicks Cough Syrup with Honey, is really just the latest incarnation of a product that Vicks parent company, Procter & Gamble (P&G), initially created for lower-income consumers in Mexico and then “trickled up” to more affluent markets.

The term “trickle up” refers to a strategy of creating products for consumers in emerging markets and then repackaging them for developed-world customers. Until recently, affluent consumers in the United States and Western Europe could afford the latest and greatest in everything. Now, with purchasing power dramatically reduced because of the global recession, budget items once again make up a growing portion of total sales in many product categories.

P&G is not the only multinational company using this strategy. Other practitioners of trickle-up innovation include General Electric (GE), Nestlé, and Nokia. In early 2008, GE Healthcare launched the MAC 400, GE’s first portable Electrocardiograph (ECG) that was designed in India for the fast-growing local market there. The company simplified elements of its earlier, 65-lb devices made for U.S. hospitals by shrinking its case to the size of a fax machine and removing features such as the keyboard and screen. The smaller MAC 400 costs only $1,500, versus $15,000 for its U.S. predecessor. This trickle-down innovation trickled back up again when GE Healthcare decided to sell the unit in Germany as well.

Nestlé offers inexpensive instant noodles in India and Pakistan under its Maggi brand. The line includes dried noodles that are engineered to taste as if they were fried, while they have a whole-wheat flavor that is popular in South Asia. And Nokia researches how people in emerging nations share phones, such as the best-selling 1100 series of devices created for developing-world consumers. The company then uses the information as inspiration for new features for developed-world users.

But what is unique about P&G’s Honey Cough, as it is also called, is that it has moved around the globe in more than one direction. Honey Cough originated in 2003 in P&G’s labs in Caracas, Venezuela, which creates products for all of Latin America. Market research revealed that Latin American shoppers tended to prefer homeopathic remedies for coughs and colds, so P&G set out to create a medicine using natural honey rather than the artificial flavors typically used. The company first introduced the syrup in Mexico, under the label VickMiel, and then in other Latin American markets, including Brazil.

P&G deduced that the product would appeal to parts of the United States that have large Hispanic populations. In 2005, the company rebranded it as Vicks Casero for sale in California and Texas, at a price slightly less than Vicks’ mainstay product, Vicks Formula 44. Within the first year of its release, the company boosted distribution to 27% more outlets.

Figuring that natural ingredients could appeal to even wider groups, P&G took the product to other markets where research indicated that homeopathic cold medicines are popular. In the past 2 years, the company has been marketing the product in Britain, France, Germany, and Italy, as well as Switzerland, and plans to add other Western European countries to the roster.

And Western Europe is not the last destination for iterations of Honey Cough. If P&G’s current market research in the greater United States shows that mainstream American shoppers will buy Honey Cough, P&G will repackage it and market it nationwide, not just as Vicks Casero in Latino markets.

Developing and marketing a new product for each nation or ethnic group can take half a decade. Trickle-up innovation can reduce this time by several years, which explains its appeal. In each rollout, P&G has needed to do little more than make adjustments for each nation’s health regulations.

At a time when companies are looking to speed product offerings while dealing with shrinking budgets and cash-strapped consumers, P&G’s experience with its Honey Cough line shows how an international product portfolio can be tapped quickly and cheaply—that is, if American companies learn how to go against the flow.

(Jana, 2009).

Core Principles of International Marketing – Chapter 8.4 by Babu John Mariadoss is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.