14.2 Can Machines Think?

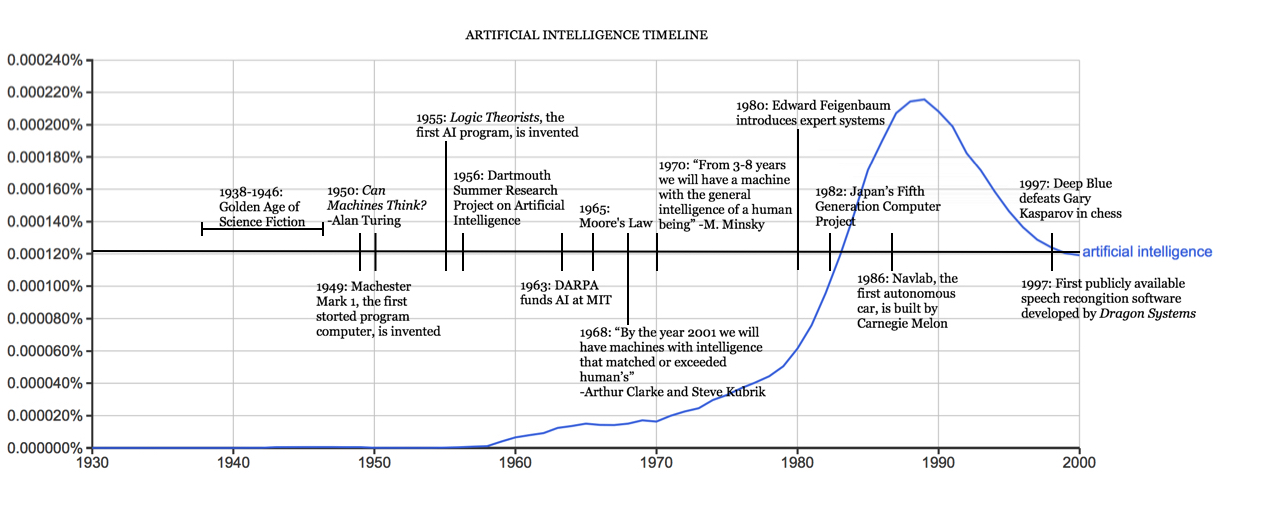

Artificial intelligence, the ability of a computer or machine to think and learn, and mimic human behaviour became the focus of many in the 1950s. Alan Turing, a young British polymath, explored the mathematical possibility of artificial intelligence. Turing suggested that humans use available information as well as reason in order to solve problems and make decisions, so why can’t machines do the same thing? This was the logical framework of his 1950 paper, Computing Machinery and Intelligence in which he discussed how to build intelligent machines and how to test their intelligence.

The Turing Test: Can Machines Think?

The Turing Test (referred to as the imitation game by Turing) was a test to determine whether or not a judge could be convinced that a computer is human. In the test, a human judge engages in a natural language conversation with a human and a machine asking questions of both. All participants are separated from one another, and the human and machine provide written responses to the questions. If the judge cannot reliably tell the machine from the human (imitating human behaviour), the machine is said to have passed the test, and therefore have the ability to think. There have been criticisms of the test, and Turing responded to some. He stated that he did not intend for the test to measure the presence of “consciousness” or “understanding”, as he did not believe this was relevant to the issues that he was addressing. The test is still referred to today.

However the test could not be executed as at the time computers lacked a key prerequisite for intelligence: they couldn’t store commands, only execute them. In other words, computers could be told what to do but couldn’t remember what they did. As well, computing was extremely expensive. In the early 1950s, the cost of leasing a computer ran up to $200,000 a month.

Five years later, the proof of concept was initialized through Allen Newell, Cliff Shaw, and Herbert Simon’s, Logic Theorist. The Logic Theorist was a program designed to mimic the problem solving skills of a human and was funded by Research and Development (RAND) Corporation. It’s considered by many to be the first artificial intelligence program and was presented at the Dartmouth Summer Research Project on Artificial Intelligence (DSRPAI) in 1956. In this historic conference, John McCarthy, imagining a great collaborative effort, brought together top researchers from various fields for an open ended discussion on artificial intelligence, the term which he coined at the very event. Sadly, the conference fell short of McCarthy’s expectations; people came and went as they pleased, and there was failure to agree on standard methods for the field. Despite this, everyone whole-heartedly aligned with the sentiment that AI was achievable. The significance of this event cannot be undermined as it catalyzed the next twenty years of AI research.

From 1957 to 1974, AI flourished. Computers could store more information and became faster, cheaper, and more accessible. Machine learning algorithms also improved and people got better at knowing which algorithm to apply to their problem. Early demonstrations such as Newell and Simon’s General Problem Solver and Joseph Weizenbaum’s ELIZA showed promise toward the goals of problem solving and the interpretation of spoken language respectively. These successes, as well as the advocacy of leading researchers (namely the attendees of the DSRPAI) convinced government agencies such as the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to fund AI research at several institutions. The government was particularly interested in a machine that could transcribe and translate spoken language as well as high throughput data processing. While the basic proof of principle was there, there was still a long way to go before the end goals of natural language processing, abstract thinking, and self-recognition could be achieved.

Information Systems for Business and Beyond: 13.2 by Shauna Roch; James Fowler; Barbara Smith; and David Bourgeois is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.