1.2 The Global Value Chain

In 1985, Michael E. Porter introduced the term ‘Value Chain’ in his book Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. Since then, this concept has been used extensively by organizations to improve their functionality and operations. The concept of ‘Value Chain’ stressed on the importance of ‘Competitive Advantage’ or being different and superior from competitors. Thus, value chain identifies how value is added throughout the creation of the final good or service produced and how operational activities costs represent a proportion of the final sale price of the good or service.

In simple words, when a company evolves into international trade and divide it’s operations across countries, they participate in global value chain.

To learn more about how the global value chain works to successfully convert cocoa beans (raw material) into chocolate (final product) watch the video: Cocoa: a sweet value chain by STDF [8:53]. It will also introduce you to some of the safety measures taken to keep food products safe, which will be discussed in detail in further chapters.

Video: Cocoa: a sweet value chain by STDF [8:53] is licensed under the Standard YouTube License. Captions and transcripts are available on YouTube.

We live in a global marketplace. The food on your table might include fresh fruit from Chile, cheese from France, and bottled water from Scotland. The clothes you wear might be designed in Italy and manufactured in China. The toys you give to a child might have come from India (Greenlaw and Shapiro, 2017). Have you ever wondered how is it possible that the products manufactured around the world are available in your nearby supermarket? The answer to such questions is International Trade. Global Trade allows countries to expand their markets and access the products which are not available domestically.

Case: Just Whose iPhone is This?

The iPhone is a global product. Apple does not manufacture iPhone components, nor does it assemble them. The assembly is done by Foxconn Corporation, a Taiwanese company, at its factory in Sengzhen, China. But, Samsung, the electronics firm and competitor to Apple, actually supplies many of the parts that make up an iPhone—representing about 26% of the costs of production. That means, that Samsung is both the biggest supplier and biggest competitor for Apple. Why do these two firms work together to produce the iPhone? To understand the economic logic behind international trade, you have to accept, as these firms do, that trade is about mutually beneficial exchange. Samsung is one of the world’s largest electronics parts suppliers. Apple lets Samsung focus on making the best parts, which allows Apple to concentrate on its strength — designing elegant products that are easy to use. If each company (and by extension each country) focuses on what it does best, there will be gains for all through trade (Greenlaw and Shapiro, 2017).

Global value chains (GVCs) have brought about revolutionary changes in international trade, industrialization, and economic development. The GVC story is still rapidly unfolding, as vividly demonstrated by the supply chain crisis, particularly for semiconductors and other components, that broke out during the COVID-19 pandemic, causing further anxiety (Alvarez et al., 2021).

Positioning Economies in Global Value Chains

With the rise of global value chains (GVCs), patterns of specialization have expanded to cover not only products but also tasks. Indeed, gross trade statistics may lead to the conclusion that an economy has a product specialization when in fact it has a functional specialization.

A case in point is developing countries with major electronics exports, such as the Philippines. These economies do not specialize in electronics, but in a particular segment in the electronics value chain (Timmer, Miroudot, and de Vries 2019).

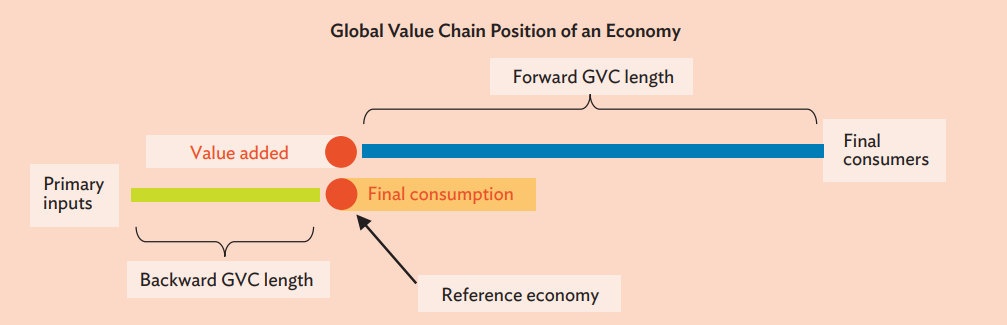

Figure 1.1 shows since the forward GVC length is noticeably longer than the backward GVC length, this economy is said to be positioned relatively upstream in GVCs.

Components of Value Chain

- In which areas of the primary and secondary activities is the firm particularly strong?

- Can that activity be leveraged to provide a competitive advantage over its rivals?

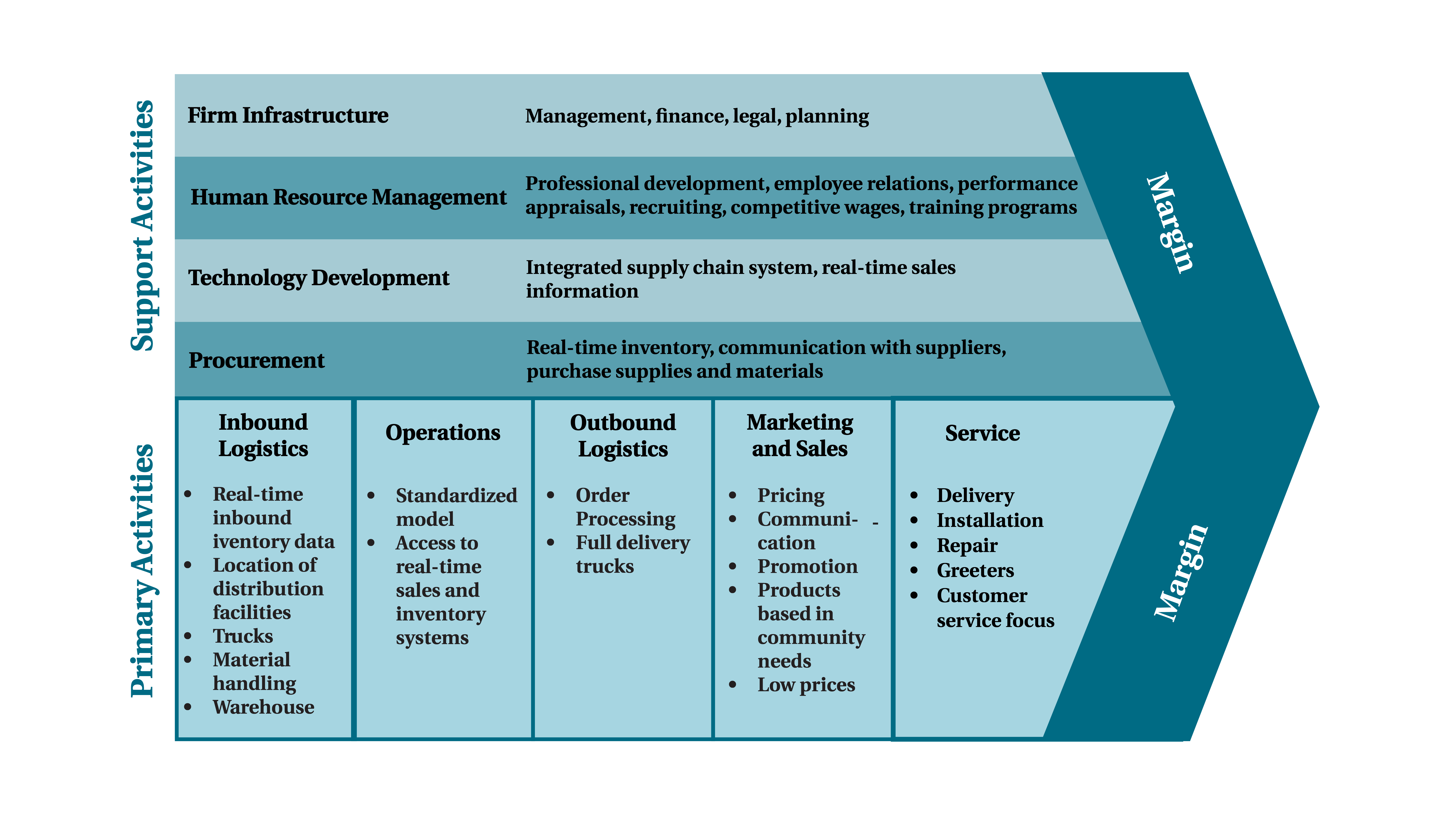

The Value Chain includes both Primary and Secondary Activities. Primary activities are actions that are directly involved in creation and distribution of goods and services. There are five primary activities in Porter’s Value Chain namely Inbound Logistics, Operations, Outbound Logistics, Marketing & Sales and Services. Secondary activities are not directly involved in the evolution of a prodct, but instead provide important underlying support for primary activities. Four activities are attributed as Secondary in Porter’s Value Chain namely Infrastructure, Human Resource Management, Technological Development and Procurement. These primary and secondary activities work together to produce a profit margin for the firm. Figure 1.2 below describes the value chain framework given by Michael Porter.

To learn more about primary and support activities, and how costs of creating value can be reduced, so that profit margin can grow, watch the video: Porter’s value chain: How to create value in your organization by MindToolsVideos [3:23].

Video: Porter’s value chain: How to create value in your organization by MindToolsVideos [3:23] is licensed under the Standard YouTube License. Captions and transcripts are available on YouTube.

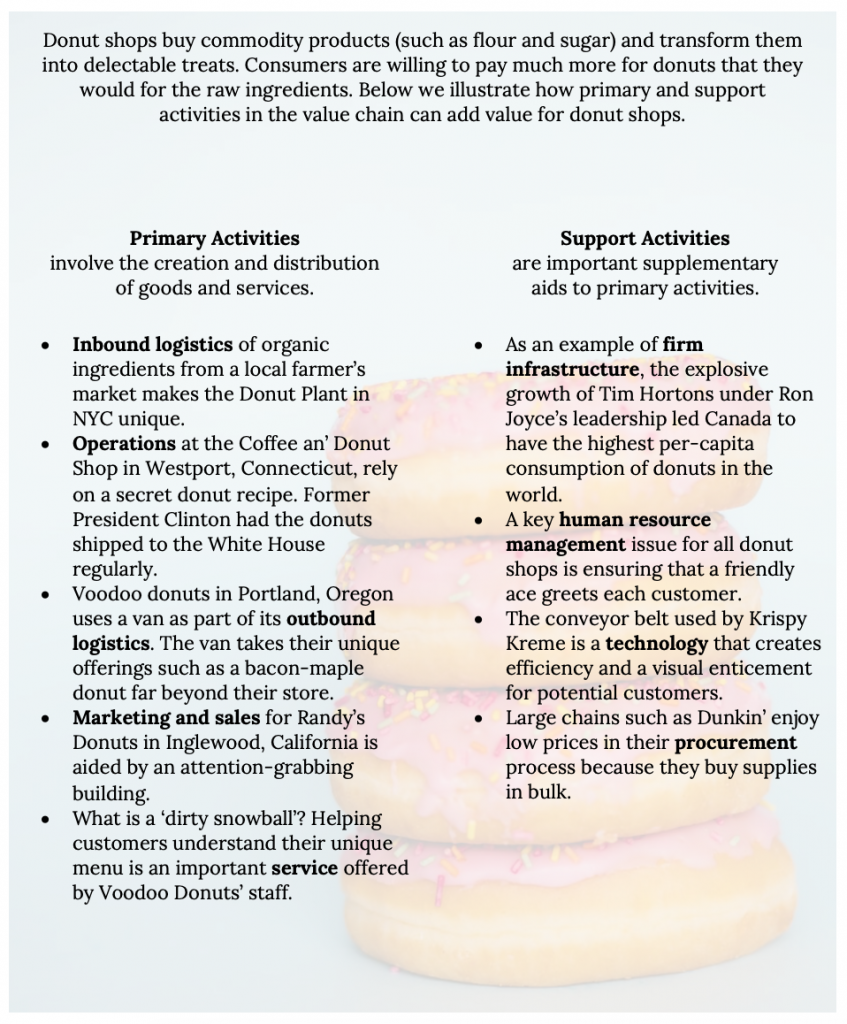

Let’s try to understand these activities from a very simple example of doughnut shops. Doughnut shops transform basic commodity products such as flour, sugar, butter, and grease into delectable treats. Value is added through this process because consumers are willing to pay much more for doughnuts than they would be willing to pay for the underlying ingredients. Figure 1.3 explains in detail how value is added while making donuts.

Donut shops buy commodity products (such as flour and sugar) and transform them into treats. Consumers are willing to pay much more for donuts than they would for the raw ingredients. See the table below which depicts how primary and support activities in the value chain add value for donut shops.

| Primary Activities | Support Activities |

|---|---|

|

|

Primary Activities

Primary Activities are essential for creating value and Competitive Advantage. There are five components of primary activities:

- Inbound Logistics: Inbound logistics refers to the arrival of raw materials. Although doughnuts are seen by most consumers as notoriously unhealthy, the Doughnut Plant in New York City has carved out a unique niche for itself by obtaining organic ingredients from a local farmer’s market.

- Operations: Operations refers to the actual production process. Operations at the Tim Horton’s or other such restaurants are trade secrets. It’s nearly impossible to make a coffee that tastes like Tim Horton’s French Vanilla at home unless you have coffee powder from Tim Horton’s.

- Outbound Logistics: Outbound logistics tracks the movement of finished products to customers. For instance, one of Southwest Airlines’ unique capabilities is moving passengers more quickly than its rivals. This advantage in operations is based in part on Southwest’s reliance on one type of airplane (which speeds maintenance) and its avoidance of advance seat assignments (which accelerates the passenger boarding process).

- Marketing and Sales: Attracting potential customers and convincing them to make purchases is the domain of marketing and sales. For example, people cannot help but notice Randy’s Donuts in Inglewood, California, because the building has a giant doughnut on top of it.

- Services: Service refers to the extent to which a firm provides assistance to their customers. Voodoo Donuts in Portland, Oregon, has developed a clever website (voodoodoughnut.com) that helps customers understand their uniquely named products, such as the Voodoo Doll, the Texas Challenge, the Memphis Mafia, and the Dirty Snowball.

Secondary Activities

Secondary/ Support Activities helps primary activities to work efficiently. There are four components of secondary activities.

- Firm Infrastructure: Firm infrastructure refers to how the firm is organized and led by executives. The effects of this organizing and leadership can be profound. For example, Ron Joyce’s leadership of Canadian doughnut shop chain Tim Hortons was so successful that Canadians consume more doughnuts per person than all other countries. In terms of resource-based theory, Joyce’s leadership was clearly a valuable and rare resource that helped his firm prosper.

- Human Resource Management: Human resource management is also important. Human resource management involves the recruitment, training, and compensation of employees. A recent research used data from more than twelve thousand organizations to demonstrate that the knowledge, skills, and abilities of a firm’s employees can act as a strategic resource and strongly influence the firm’s performance (Crook et al., 2011). Certainly, the unique level of dedication demonstrated by employees at Southwest Airlines has contributed to that firm’s excellent performance over several decades.

- Technology: Technology refers to the use of computerization and telecommunications to support primary activities. Although doughnut making is not a high-tech business, technology plays a variety of roles for doughnut shops, such as allowing customers to pay using credit cards.

- Procurement: Procurement is the process of negotiating for and purchasing raw materials. Large doughnut chains such as Dunkin’ and Krispy Kreme can gain cost advantages over their smaller rivals by purchasing flour, sugar, and other ingredients in bulk. Meanwhile, Southwest Airlines has gained an advantage over its rivals by using futures contracts within its procurement process to minimize the effects of rising fuel prices.

More Value Chain Examples

Would you like to know about value chain of Canadian Pacific Railways and Apple. Review these resources:

Global Value Chain 1.2 Components of Global Value Chain by Dr. Kiranjot Kaur and Iuliia Kau is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Principles of Microeconomics 2e: Introduction to International Trade by Open Stax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0