5.3 A Firm’s External Macro Environment: PESTEL

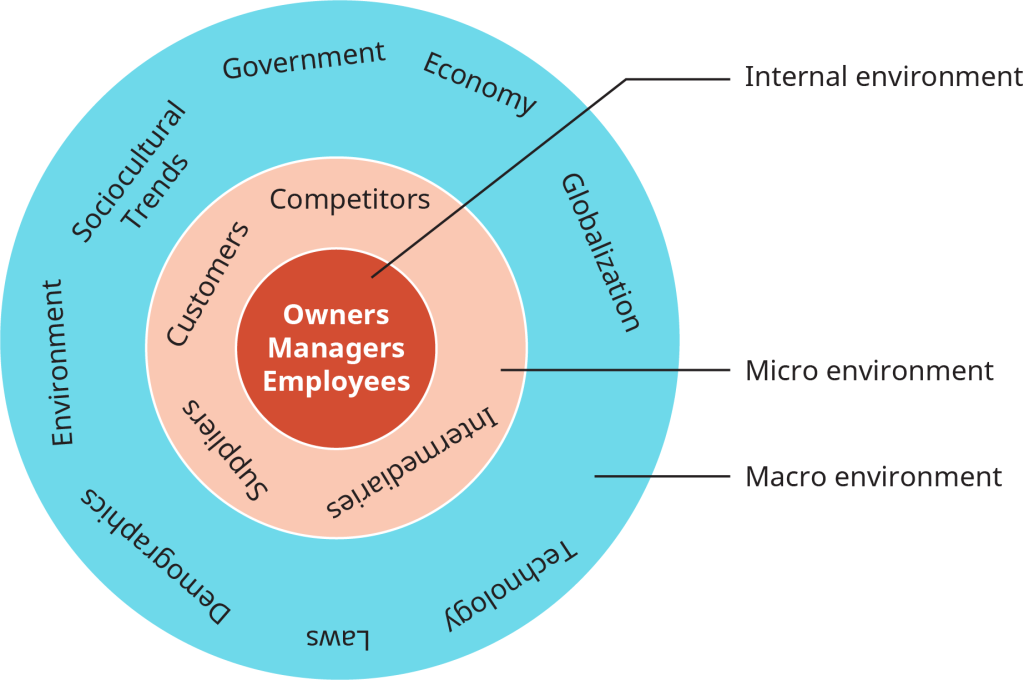

The world at large forms the external environment for businesses. A firm must confront, adapt to, take advantage of, and defend itself against what is happening in the world around it to succeed. To make gathering and interpreting information about the external environment easier, strategic analysts have defined several general categories of activities and groups that managers should examine and understand. Figure 5.2 illustrates layers and categories found in a firm’s environment.

Image © Rice University & OpenStax, CC BY 4.0

A firm’s macro environment contains elements that can impact the firm but are generally beyond its direct control. These elements are characteristics of the world at large and are factors that all businesses must contend with, regardless of the industry they are in or type of business they are. In the Figure 5.2, the macro environment is indicated in blue. Note that the terms contained in the blue ring are all “big-picture” items that exist independently of business activities. That is not to say that they do not affect firms or that firm activities cannot affect macro environmental elements; both can and do happen, but firms are largely unable to directly change things in the macro environment.

Strategists study the macro environment to learn about facts and trends that may present opportunities or threats to their firms. However, they do not usually just think in terms of SWOT. Strategists have developed more discerning tools to examine the external environment.

PESTEL Analysis

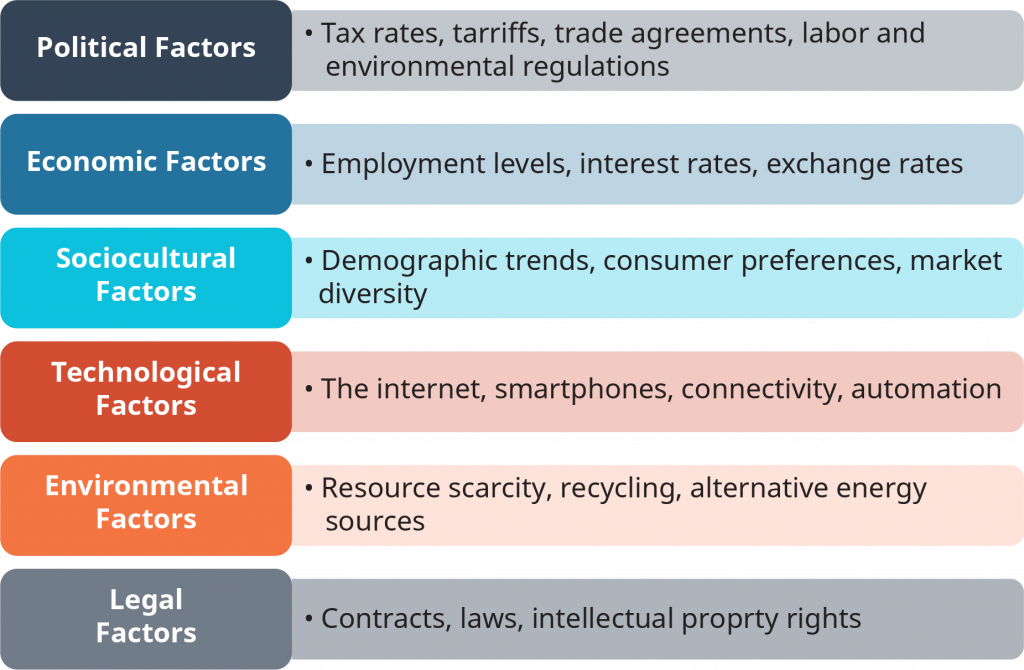

PESTEL analysis is an important and widely used tool that helps show the big picture of a firm’s external environment, particularly as related to foreign markets. PESTEL is an acronym for the political, economic, sociocultural, technological, environmental, and legal contexts in which a firm operates. A PESTEL analysis helps managers gain a better understanding of the opportunities and threats they face; consequently, the analysis aids in building a better vision of the future business landscape and how the firm might compete profitably. This useful tool analyzes for market growth or decline and, therefore, the position, potential, and direction for a business. When a firm is considering entry into new markets, these factors are of considerable importance. Moreover, PESTEL analysis provides insight into the status of key market flatteners, both in terms of their present state and future trends.

Firms need to understand the macroenvironment to ensure that their strategy is aligned with the powerful forces of change affecting their business landscape. When firms exploit a change in the environment—rather than simply survive or oppose the change—they are more likely to be successful. A solid understanding of PESTEL also helps managers avoid strategies that may be doomed to fail given the circumstances of the environment.

Finally, understanding PESTEL is critical prior to entry into a new country or region. The fact that a strategy is congruent with PESTEL in the home environment gives no assurance that it will also align in other countries. For example, when Lands’ End, the online clothier, sought to expand its operations into Germany, it ran into local laws prohibiting it from offering unconditional guarantees on its products. In the United States, Lands’ End had built a reputation for quality on its no-questions-asked money-back guarantee. However, this was considered illegal under Germany’s regulations governing incentive offers and price discounts. The political skirmish between Lands’ End and the German government finally ended when the regulations banning unconditional guarantees were abolished. While the restrictive regulations didn’t put Lands’ End out of business in Germany, they did inhibit its growth there until the laws were abolished.

There are three steps in the PESTEL analysis. First, consider the relevance of each of the PESTEL factors to your context. Next, identify and categorize the information that applies to these factors. Finally, analyze the data and draw conclusions. Common mistakes in this analysis include stopping at the second step or assuming that the initial analysis and conclusions are correct without testing the assumptions and investigating alternative scenarios.

Examples of elements analyzed in each of these segments are shown in Table 5.1.

| Political | Economic |

|---|---|

| How stable is the political environment? | What are current and forecasted interest rates? |

| What are local taxation policies, and how do these affect your business? | What is the level of inflation, what is it forecast to be, and how does this affect the growth of your market? |

| Does the government have trade agreements such as EU, NAFTA, ASEAN, or others? | What are local employment levels per capita and how are they changing? |

| What are the foreign trade regulations? | What are the long-term prospects for the economy gross domestic product (GDP) per capita, and so on? |

| What are the social welfare policies? | What are exchange rates between critical markets and how will they affect production and distribution of your goods? |

| Social or Socio-cultural | Technical or Technological |

| What are local lifestyle trends? | What is the level of research funding in government and the industry, and are those levels changing? |

| What are the current demographics, and how are they changing? | What is the government and industry’s level of interest and focus on technology? |

| What is the level and distribution of education and income? | How mature is the technology? |

| What are the dominant local religions and what influence do they have on consumer attitudes and opinions? | What is the status of intellectual property issues in the local environment? |

| What is the level of consumerism and popular attitudes toward it? | Are potentially disruptive technologies in adjacent industries creeping in at the edges of the focal industry? |

| What pending legislation is there that affects corporate social policies (e.g., domestic partner benefits, maternity/paternity leave)? | How fast is technology changing? How is its pace impacting the industry? |

| What are the attitudes toward work and leisure? | What role does technology play in competitive advantage? |

| Environmental | Legal |

| What are local environmental issues? | What are the regulations regarding monopolies and private property? |

| Are there any ecological or environmental issues relevant to your industry that are pending? | Does intellectual property have legal protections? |

| How do the activities of international pressure groups affect your business (e.g., Greenpeace, Earth First, PETA)? | Are there relevant consumer laws? |

| Are there environmental protection laws? What are the regulations regarding waste disposal and energy consumption? | What is the status of employment, health and safety, and product safety laws? |

Figure 5.3 illustrates the components of PESTEL, which will be discussed individually below.

Image © Rice University & OpenStax, CC BY 4.0

Political Factors

Political factors in the macro environment include taxation, tariffs, trade agreements, labour regulations, and environmental regulations. Note that in PESTEL, factors are not characterized as opportunities or threats. They are simply things that a firm can take advantage of or treat as problems, depending on its own interpretation or abilities. American Electric Power, a large company that generates and distributes electricity, may be negatively impacted by environmental regulations that restrict its ability to use coal to generate electricity because of pollution caused by burning coal. However, another energy firm has taken advantage of the government’s interest in reducing coal emissions by developing a way to capture the emissions while producing power. The Petra Nova plant, near Houston, was developed by NRG and JX Nippon, who received Energy Department grants to help fund the project (Mooney, 2017). Although firms do not directly make government policy decisions, many industries and firms invest in lobbying efforts to try to influence government policy development to create opportunities or reduce threats.

Economic Factors

All firms are impacted by the state of the national and global economies. The increased interdependence of individual country economies has made evaluating the economic factors in a firm’s macro environment more complex. Firms analyze economic indicators to make decisions about entering or exiting geographic markets, investing in expansion, and hiring or laying off employees. As discussed earlier in this chapter, employment rates impact the quantity, quality, and cost of employees available to firms. Interest rates impact sales of big-ticket items that consumers normally finance, such as appliances, cars, and homes. Interest rates also impact the cost of capital for firms that want to invest in expansion. Exchange rates present risks and opportunities to all firms that operate across national borders, and the price of oil impacts many industries, from airlines and transportation companies to solar panel producers and plastic recycling companies. Once again, any scenario can be a threat to one firm and an opportunity to another, so economic forces should not be assumed to be intrinsically good or bad.

Sociocultural Factors

Quite possibly the largest category of macro environmental factors an analyst might examine are sociocultural factors. This broad category encompasses everything from changing national demographics to fashion trends and many things in between. Demographics, a subset of this category, includes facts about income, education levels, age groups, and the ethnic and racial composition of a population. All of these facts present market challenges and possibilities. Firms can target products to specific market segments by studying the needs and preferences of demographic groups, such as working women (they might need day-care services but not watch daytime television), college students (who would be interested in affordable textbooks but couldn’t afford to buy new cars), or the elderly (who would be willing to pay for lawn-mowing services but might not be interested in adventure tourism).

Changes in people’s values and interests are also included in this category. Environmental awareness has spurred demand for solar panels and electric and hybrid cars. A general interest in health and fitness has created industries in gyms, home gym equipment, and organic food. The popularity of social media has created an enormous demand for instant access to information and services, not to mention smartphones. Values and interests are constantly changing and vary from country to country, creating new market opportunities as well as communication challenges for companies trying to enter unfamiliar new markets.

Technological Factors

The rise of the Internet may be the most disruptive technological change of the last century. The globe has become more interconnected and interdependent because of the fast, low-cost communications the Internet provides. Customer service agents in India can serve customers in Kansas because technology has advanced to the point that the customer’s account information can be instantly accessed by the service provider in India. Entrepreneurs around the world can reach customers anywhere through companies such as eBay, Alibaba, and Etsy, and they can get paid, regardless of their customers’ currency, through PayPal. The Internet has enabled Jeff Bezos, who started an online bookselling company called Amazon in 1994, to transform how consumers shop for goods.

How else have technological factors impacted business? The Internet is not the only technological advance that has transformed how businesses operate. Automation has increased efficiency for manufacturers. MRP (materials requirement planning) systems have changed how companies and their suppliers work together, and global-positioning technology has helped construction engineers manage large projects more accurately. Consumers and firms have nearly unlimited access to information, and this access has empowered consumers to make more-informed buying decisions and challenged firms to develop ways to analyze the large amounts of data their businesses generate.

Environmental Factors

The physical environment, which provides natural resources for manufacturing and energy production, has always been a key part of human business activity. As resources become scarcer and more expensive, environmental factors impact businesses more every day. Firms are developing technology to operate more cleanly and using fewer resources. Political pressure on businesses to reduce their impact on the natural environment has increased globally and dramatically in the 21st century. In 2017, London, Barcelona, and Paris announced their plans to ban cars with internal combustion engines over the next few decades, in order to combat air-quality issues (Smith, 2017).

This external environment category often overlaps with others in PESTEL because concern for the environment is also a sociocultural trend, as more consumers look for recycled products and buy electric and hybrid cars. On the political front, firms are facing increased regulation around the world on their carbon emissions and natural resource use. Although SWOT would characterize these factors as either opportunities or threats, PESTEL simply identifies them as aspects of the external environment that firms must consider when planning for their futures.

Legal Factors

Legal factors in the external environment often coincide with political factors because laws are enacted by government entities. This does not mean that the categories identify the same issues, however. Although labour laws and environmental regulations have deep political connections, other legal factors can impact business success. For example, in the streaming video industry, licensing fees are a significant cost for firms. Netflix pays billions of dollars every year to movie and television studios for the right to broadcast their content. In addition to the legal requirement to pay the studios, Netflix must consider that consumers may find illegal ways to view the movies they want to see, making them less willing to pay to subscribe to Netflix. Intellectual property rights and patents are major issues in the legal realm.

Note that some external factors are difficult to categorize in PESTEL. For instance tariffs can be viewed as either a political or economic factor while the influence of the internet could be viewed as either a technological or social factor. While some issues can overlap two or more PESTEL areas, it does not diminish the value of PESTEL as an analytical tool.

Impact of PESTEL Factors on an Entire Industry

As coronavirus’s impact continued to expand, regulators in countries such as the U.K. began urging companies to conduct risk assessments. The outbreak has caused damage to supply chains in China and internationally. The debt and asset positions of many companies have been affected, the share prices of international companies, and the volume of business in China have fallen sharply. The PESTEL analysis confirms its importance. The whole business environment will be affected by similar emergencies in the future, and companies need to make strategic plans according to PESTEL to reduce their risks after emergencies (Ojea, 2020).

PESTEL and Globalization

Over the past decade, new markets have been opened to foreign competitors, whole industries have been deregulated, and state-run enterprises have been privatized. Globalization involves much more than companies simply exporting products to another country. Some industries that aren’t normally considered global do, in fact, have strictly domestic players. But these companies often compete alongside firms with operations in multiple countries; in many cases, both sets of firms are doing equally well. In contrast, in a truly global industry, the core product is standardized, the marketing approach is relatively uniform, and competitive strategies are integrated in different international markets (Porter, 1986). In these industries, competitive advantage clearly belongs to the firms that can compete globally.

A number of factors reveal whether an industry has globalized or is in the process of globalizing. The sidebar below groups globalization factors into four categories: markets, costs, governments, and competition. These dimensions correspond well to Thomas Friedman’s flatteners (as described in his book The World Is Flat), though they are not exhaustive (Friedman, 2005).

Factors Favouring Industry Globalization

- Markets

o Homogeneous customer needs

o Global customer needs

o Global channels

o Transferable marketing approaches

2. Costs

o Large-scale and large-scope economies

o Learning and experience

o Sourcing efficiencies

o Favourable logistics

o Arbitrage opportunities

o High research-and-development (R&D) costs

3. Governments

o Favourable trade policies

o Common technological standards

o Common manufacturing and marketing regulations

4. Competition

o Interdependent countries

o Global competitors(Porter, 1986).

Markets

The more similar markets in different regions are, the greater the pressure for an industry to globalize. Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, for example, are fairly uniform around the world because the demand for soft drinks is largely the same in every country. The airframe-manufacturing industry, dominated by Boeing and Airbus, also has a highly uniform market for its products; airlines all over the world have the same needs when it comes to large commercial jets.

Costs

In both of these industries, costs favour globalization. Coca-Cola and PepsiCo realize economies of scope and scale because they make such huge investments in marketing and promotion. Since they’re promoting coherent images and brands, they can leverage their marketing dollars around the world. Similarly, Boeing and Airbus can invest millions in new-product R&D only because the global market for their products is so large.

Governments and Competition

Obviously, favourable trade policies encourage the globalization of markets and industries. Governments, however, can also play a critical role in globalization by determining and regulating technological standards. Railroad gauge—the distance between the two steel tracks—would seem to favour a simple technological standard. In Spain, however, the gauge is wider than in France. Why? Because back in the 1850s, when Spain and neighbouring France were hostile to one another, the Spanish government decided that making Spanish railways incompatible with French railways would hinder any French invasion.

These are a few key drivers of industry change. However, there are particular implications of technological and business-model breakthroughs for both the pace and extent of industry change. The rate of change may vary significantly from one industry to the next; for instance, the computing industry changes much faster than the steel industry. Nevertheless, change in both fields has prompted complete reconfigurations of industry structure and the competitive positions of various players. The idea that all industries change over time and that business environments are in a constant state of flux is relatively intuitive. As a strategic decision maker, you need to ask yourself this question: how accurately does current industry structure (which is relatively easy to identify) predict future industry conditions?

Importing as a Stealth Form of Internationalization

Ironically, the drivers of globalization have also given rise to a greater level of imports. Globalization in this sense is a very strong flattener. Importing involves the sale of products or services in one country that are sourced in another country. In many ways, importing is a stealth form of internationalization. Firms often claim that they have no international operations and yet—directly or indirectly—base their production or services on inputs obtained from outside their home country. Firms that engage in importing must learn about customs requirements, informed compliance with customs regulations, entry of goods, invoices, classification and value, determination and assessment of duty, special requirements, fraud, marketing, trade finance and insurance, and foreign trade zones. Importing can take many forms—from the sourcing of components, machinery, and raw materials to the purchase of finished goods for domestic resale and the outsourcing of production or services to nondomestic providers.

Outsourcing occurs when a company contracts with a third party to do some work on its behalf. The outsourcer may do the work within the same country or may take the work to another country (i.e., offshoring). Offshoring occurs when you take a function out of your country of residence to be performed in another country, generally at a lower cost. International outsourcing, or outsourcing work to a nondomestic third party, has become very visible in business and corporate strategy in recent years. But it’s not a new phenomenon; for decades, Nike has been designing shoes and other apparel that are manufactured abroad. Similarly, Pacific Cycle doesn’t make a single Schwinn or Mongoose bicycle in the United States but instead imports them entirely from manufacturers in Taiwan and China. It may seem as if international outsourcing is new because businesses are now more often outsourcing services, components, and raw materials from countries with developing economies (e.g., China, Brazil, and India).

In addition to factors of production, information technologies (IT)—such as telecommunications and the widespread diffusion of the Internet—have provided the impetus for outsourcing services. Business-process outsourcing (BPO) is the delegation of one or more IT-intensive business processes to an external provider that in turn owns, administers, and manages the selected process on the basis of defined and measurable performance criteria. The firms in service and IT-intensive industries—insurance, banking, pharmaceuticals, telecommunications, automotive, and airlines—are among the early adopters of BPO. Of these, insurance and banking are able to generate the bulk of the savings, purely because of the large proportion of processes that they can outsource (i.e., the processing of claims and loans and providing service through call centres). Among those countries housing BPO operations, India experienced the most dramatic growth in services where language skills and education were important.

Case: Sustainability and Responsible Management – Can LEGO Give up Plastic?

“In 2012, the LEGO Group first shared its ambition to find and implement sustainable alternatives to the current raw materials used to manufacture LEGO products by 2030. The ambition is part of the LEGO Group’s work to reduce its environmental footprint and leave a positive impact on the planet our children will inherit.” (Trangæk, 2015, para. 7).

Danish toy company LEGO announced in 2015 that it would invest almost $160 million dollars into its efforts to meet the goal it announced in 2012. You know LEGO—they are the coloured plastic bricks that snap together to make toys ranging from Harry Potter castles to Star Wars fighter craft. The family-owned company was founded in 1932 by Ole Kirk Christiansen and has since grown to be the world’s number one toy brand (Brand Finance, 2017).

Given that LEGO and plastic seem to go hand in hand, why would the company want to give up on the material that makes their toys so successful? LEGO’s manufacturing process relies on plastic to make highly precise plastic bricks that always fit together securely and easily. Replacing the plastic with another material that is durable, can be brightly coloured, and can be molded as precisely is a difficult task. LEGO’s leadership has decided that a strategic position based on fossil fuels is not sustainable and is making plans now to transition to a more environmentally friendly material to manufacture its products.

Switching from oil-based plastic might make economic sense as well. Manufacturers who rely on petroleum-based products must weather volatile oil prices. LEGO’s raw materials costs could skyrocket overnight if the price of oil climbs again as it did in 2011. That price spike was due to conflict in Libya and other parts of the Arab world (Holodny, 2016), something entirely beyond the control of any business.

Technological innovations in bio-based plastics may be the answer for LEGO (Peters, 2015), which is working with university researchers around the globe to find a solution to its carbon-footprint problem.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How would you approach this issue if you were the manager in charge of sourcing raw materials for LEGO? How would PESTEL analysis inform your actions?

- What PESTEL challenges is LEGO trying to address by changing the raw materials used in its products?

- Explain what favorable PESTEL factors support LEGO’s efforts.

Core Principles of International Marketing – Chapter 6.2 by Babu John Mariadoss is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Principles of Management – Chapter 8.3 by David S. Bright, et al., © Open Stax is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, unless otherwise noted.

Strategic Management 2E by John Morris is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.