4.7 Target Market Selection

Few companies can afford to enter all markets open to them. Even the world’s largest companies must exercise strategic discipline in choosing the markets they serve. They must also decide when to enter them and weigh the relative advantages of a direct or indirect presence in different regions of the world. Small and midsized companies are often constrained to an indirect presence; for them, the key to gaining a global competitive advantage is often creating a worldwide resource network through alliances with suppliers, customers, and, sometimes, competitors. What is a good strategy for one company, however, might have little chance of succeeding for another.

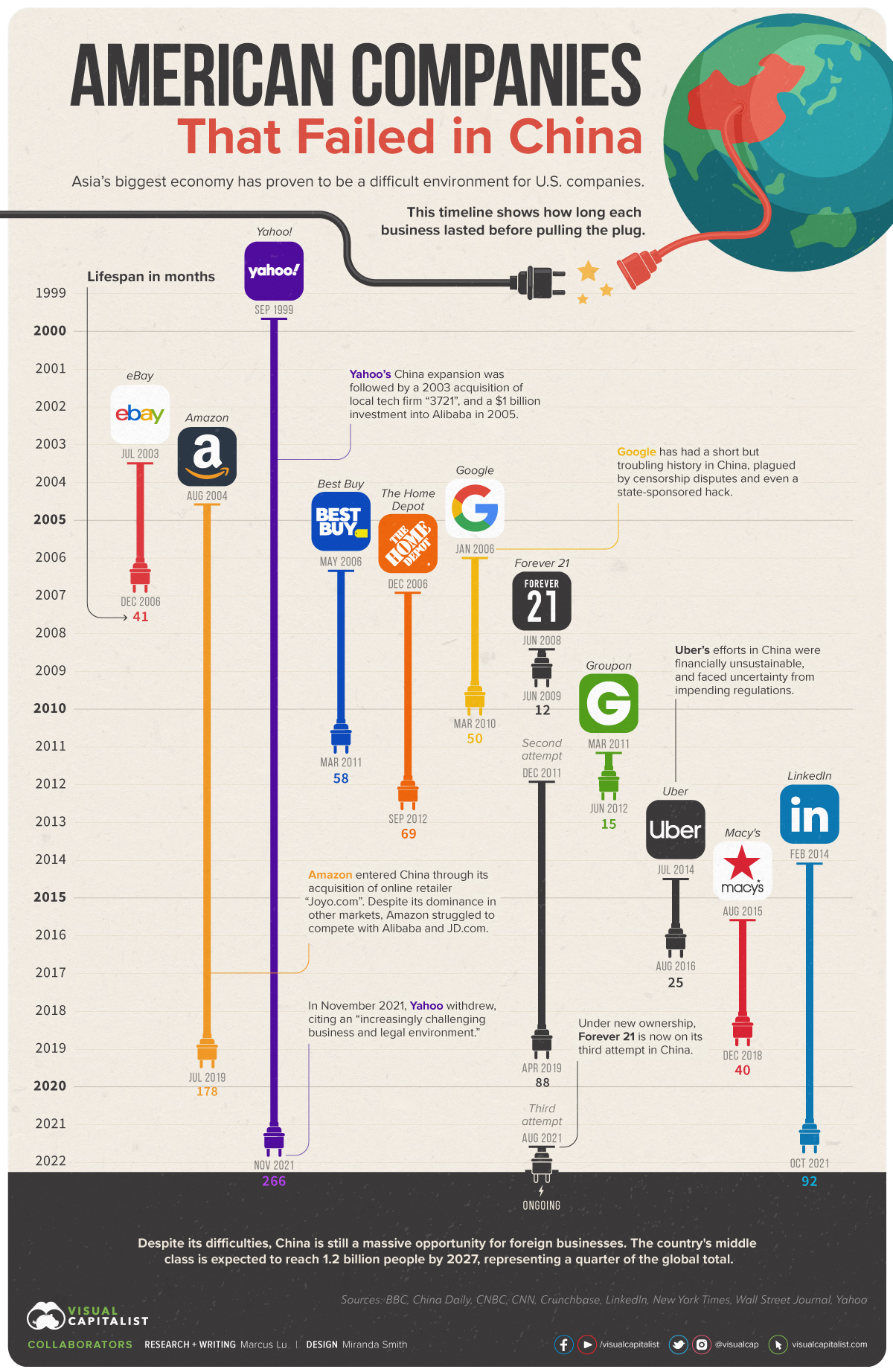

The track record shows that picking the most attractive foreign markets, determining the best time to enter them, and selecting the right partners and level of investment has proven difficult for many companies, especially when it involves large emerging markets such as China. For example, it is now generally recognized that Western carmakers entered China far too early and overinvested, believing a “first-mover advantage” would produce superior returns. Reality was very different. Most companies lost large amounts of money, had trouble working with local partners, and saw their technological advantage erode due to “leakage.” None achieved the sales volume needed to justify their investment.

Even highly successful global companies often first sustain substantial losses on their overseas ventures, and occasionally have to trim back their foreign operations or even abandon entire countries or regions in the face of ill-timed strategic moves or fast-changing competitive circumstances. What makes global market selection and entry so difficult? Research shows there is a pervasive the-grass-is-always-greener effect that infects global strategic decision-making in many, especially globally inexperienced, companies and causes them to overestimate the attractiveness of foreign markets. Distance can be a major impediment to global success: cultural differences can lead companies to overestimate the appeal of their products or the strength of their brands; administrative differences can slow expansion plans, reduce the ability to attract the right talent, and increase the cost of doing business; geographic distance impacts the effectiveness of communication and coordination, and economic distance directly influences revenues and costs (Ghemawat, 2001).

A related issue is that developing a global presence takes time and requires substantial resources. Ideally, the pace of international expansion is dictated by customer demand. Sometimes it is necessary, however, to expand ahead of direct opportunity in order to secure a long-term competitive advantage. But as many companies that entered China in anticipation of its membership in the World Trade Organization have learned, early commitment to even the most promising long-term market makes earning a satisfactory return on invested capital difficult. As a result, an increasing number of firms, particularly smaller and mid-sized ones, favour global expansion strategies that minimize direct investment. Strategic alliances have made vertical or horizontal integration less important to profitability and shareholder value in many industries. Alliances boost contribution to fixed costs while expanding a company’s global reach. At the same time, they can be powerful windows on technology and greatly expand opportunities to create the core competencies needed to effectively compete on a worldwide basis.

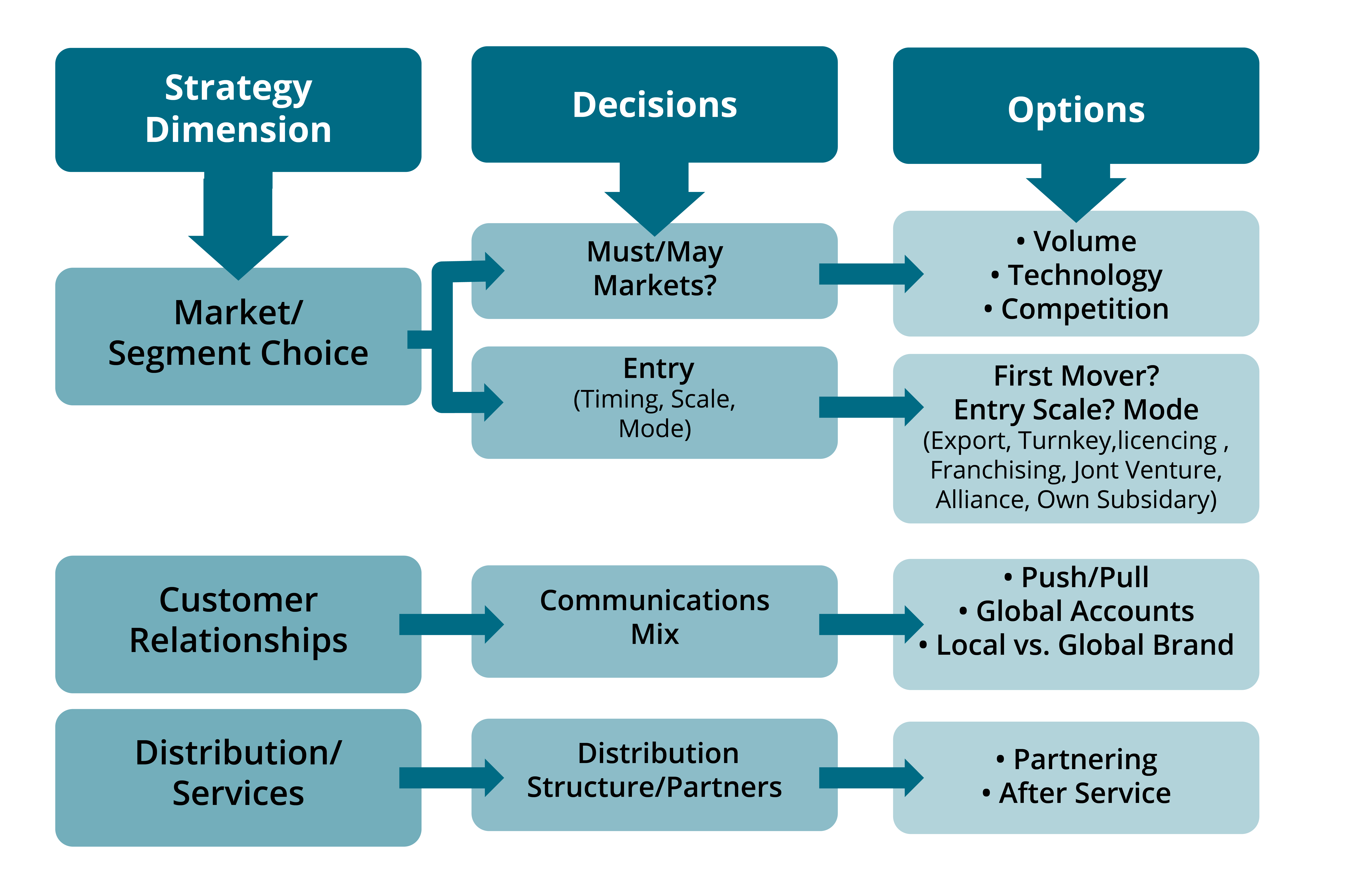

Finally, a complicating factor is that a global evaluation of market opportunities requires a multidimensional perspective. In many industries, we can distinguish between “must” markets—markets in which a company must compete in order to realize its global ambitions—and “nice-to-be-in” markets—markets in which participation is desirable but not critical. “Must” markets include those that are critical from a volume perspective, markets that define technological leadership, and markets in which key competitive battles are played out. In the cell phone industry, for example, Motorola looks to Europe as a primary competitive battleground, but it derives much of its technology from Japan and sales volume from the United States.

American Companies That Failed In China

Despite the size and potential of the market, China is not an easy place for foreign businesses to enter. As this infographic shows, many of America’s biggest names eventually admitted defeat.

Core Principles of International Marketing – Chapter 6.8 by Babu John Mariadoss is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.