3.2 Describing Culture: Hofstede

The study of cross-cultural analysis incorporates the fields of anthropology, sociology, psychology, and communication. The combination of cross-cultural analysis and business is a new and evolving field; it’s not a static understanding but changes as the world changes. Within cross-cultural analysis, two names dominate our understanding of culture—Geert Hofstede and Edward T. Hall. Although new ideas are continually presented, Hofstede remains the leading thinker on how we see cultures.

This page will review both the thinkers and the main components of how they define culture and the impact on communications and business. At first glance, it may seem irrelevant to daily business management to learn about these approaches. In reality, despite the evolution of cultures, these methods provide a comprehensive and enduring understanding of the key factors that shape a culture, which in turn impact every aspect of doing business globally. Additionally, these methods enable us to compare and contrast cultures more objectively. By understanding the key researchers, you’ll be able to formulate your own analysis of the different cultures and the impact on international business.

Hofstede and Values

Geert Hofstede, sometimes called the father of modern cross-cultural science and thinking, is a social psychologist who focused on a comparison of nations using a statistical analysis of two unique databases. The first and largest database composed of answers that matched employee samples from forty different countries to the same survey questions focused on attitudes and beliefs. The second consisted of answers to some of the same questions by Hofstede’s executive students who came from fifteen countries and from a variety of companies and industries. He developed a framework for understanding the systematic differences between nations in these two databases. This framework focused on value dimensions. Values, in this case, are broad preferences for one state of affairs over others, and they are mostly unconscious.

Most of us understand that values are our own culture’s or society’s ideas about what is good, bad, acceptable, or unacceptable. Hofstede developed a framework for understanding how these values underlie organizational behaviour. Through his database research, he identified five key value dimensions that analyze and interpret the behaviours, values, and attitudes of a national culture:

- Power distance

- Individualism

- Masculinity

- Uncertainty avoidance (UA)

- Long-term orientation (Hofstede, 2011).

- Indulgence

Power distance

Power distance refers to how openly a society or culture accepts or does not accept differences between people, as in hierarchies in the workplace, in politics, and so on.

For example, high power distance cultures openly accept that a boss is “higher” and as such deserves a more formal respect and authority. Examples of these cultures include Japan, Mexico, and the Philippines. In Japan or Mexico, the senior person is almost a father figure and is automatically given respect and usually loyalty without questions.

In Southern Europe, Latin America, and much of Asia, power is an integral part of the social equation. People tend to accept relationships of servitude. An individual’s status, age, and seniority command respect—they’re what make it all right for the lower-ranked person to take orders. Subordinates expect to be told what to do and won’t take initiative or speak their minds unless a manager explicitly asks for their opinion.

At the other end of the spectrum are low power distance cultures, in which superiors and subordinates are more likely to see each other as equal in power. Countries found at this end of the spectrum include Austria and Denmark. To be sure, not all cultures view power in the same ways. In Sweden, Norway, and Israel, for example, respect for equality is a warranty of freedom. Subordinates and managers alike often have carte blanche to speak their minds.

Interestingly enough, research indicates that the United States tilts toward low power distance but is more in the middle of the scale than Germany and the United Kingdom.

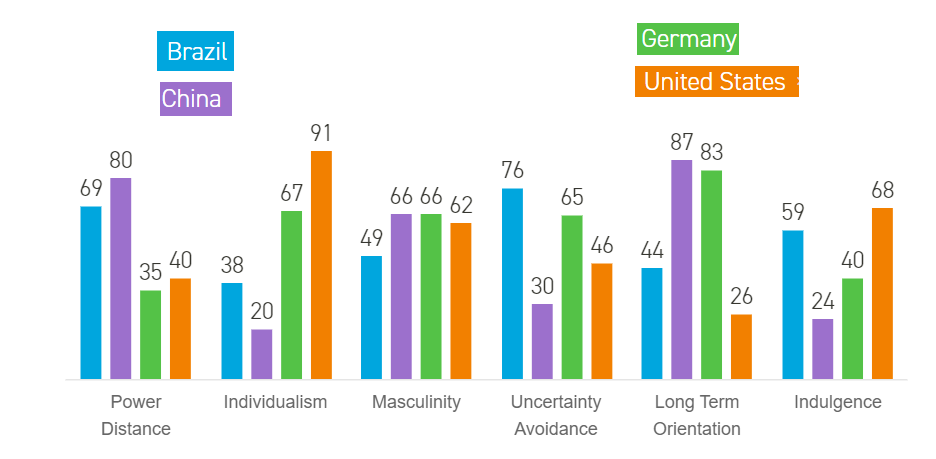

Let’s look at the culture of the United States, Germany, Brazil and China in relation to these five dimensions. The United States actually ranks somewhat lower in power distance—forty as noted in the figure below. The United States has a culture of promoting participation at the office while maintaining control in the hands of the manager. People in this type of culture tend to be relatively laid-back about status and social standing—but there’s a firm understanding of who has the power.

Individualism

Individualism is just what it sounds like. It refers to people’s tendency to take care of themselves and their immediate circle of family and friends, perhaps at the expense of the overall society. In individualistic cultures, what counts most is self-realization. Initiating alone, sweating alone, achieving alone—not necessarily collective efforts—are what win applause. In individualistic cultures, competition is the fuel of success.

The United States and Northern European societies are often labelled as individualistic. In the United States, individualism is valued and promoted—from its political structure (individual rights and democracy) to entrepreneurial zeal (capitalism). Other examples of high-individualism cultures include Australia and the United Kingdom.

On the other hand, in collectivist societies, group goals take precedence over individuals’ goals. Basically, individual members render loyalty to the group, and the group takes care of its individual members. Rather than giving priority to “me,” the “us” identity predominates. Of paramount importance is pursuing the common goals, beliefs, and values of the group as a whole—so much so, in some cases, that it’s nearly impossible for outsiders to enter the group. Cultures that prize collectivism and the group over the individual include Singapore, Korea, Mexico, and Arab nations. The protections offered by traditional Japanese companies come to mind as a distinctively group-oriented value.

Masculinity

The next dimension is masculinity, which may sound like an odd way to define a culture. When we talk about masculine or feminine cultures, we’re not talking about diversity issues. It’s about how a society views traits that are considered masculine or feminine.

This value dimension refers to how a culture ranks on traditionally perceived “masculine” values: assertiveness, materialism, and less concern for others. In masculine-oriented cultures, gender roles are usually crisply defined. Men tend to be more focused on performance, ambition, and material success. They cut tough and independent personas, while women cultivate modesty and quality of life. Cultures in Japan and Latin America are examples of masculine-oriented cultures.

In contrast, feminine cultures are thought to emphasize “feminine” values: concern for all, an emphasis on the quality of life, and an emphasis on relationships. In feminine-oriented cultures, both genders swap roles, with the focus on quality of life, service, and independence. The Scandinavian cultures rank as feminine cultures, as do cultures in Switzerland and New Zealand. The United States is actually more moderate, and its score is ranked in the middle between masculine and feminine classifications. For all these factors, it’s important to remember that cultures don’t necessarily fall neatly into one camp or the other.

Uncertainty Avoidance

The next dimension is uncertainty avoidance (UA). This refers to how much uncertainty a society or culture is willing to accept. It can also be considered an indication of the risk propensity of people from a specific culture. People who have high uncertainty avoidance generally prefer to steer clear of conflict and competition. They tend to appreciate very clear instructions. At the office, sharply defined rules and rituals are used to get tasks completed. Stability and what is known are preferred to instability and the unknown. Company cultures in these countries may show a preference for low-risk decisions, and employees in these companies are less willing to exhibit aggressiveness. Japan and France are often considered clear examples of such societies.

Long-term Orientation

The fifth dimension is long-term orientation, which refers to whether a culture has a long-term or short-term orientation. This dimension was added by Hofstede after the original four you just read about. It resulted in the effort to understand the difference in thinking between the East and the West. Certain values are associated with each orientation. The long-term orientation values persistence, perseverance, thriftiness, and having a sense of shame. These are evident in traditional Eastern cultures. Based on these values, it’s easy to see why a Japanese CEO is likely to apologize or take the blame for a faulty product or process.

Long- and short-term orientation and the other value dimensions in the business arena are all evolving as many people earn business degrees and gain experience outside their home cultures and countries, thereby diluting the significance of a single cultural perspective. As a result, in practice, these five dimensions do not occur as single values but are really woven together and interdependent, creating very complex cultural interactions. Even though these five values are constantly shifting and not static, they help us begin to understand how and why people from different cultures may think and act as they do. Hofstede’s study demonstrates that there are national and regional cultural groupings that affect the behaviour of societies and organizations and that these are persistent over time.

Indulgence (vs. Restraint)

The sixth dimension is Indulgence. This dimension is a relatively new addition to the model. It is described as how far people try to moderate their urges and impulses as a result of their upbringing. Indulgence is a term for a lack of control, while restraint is a term for firm control. This means cultures might be classified as either indulgent or restrained. Indulgence refers to a culture that provides for the relatively unrestricted satisfaction of basic and natural human desires such as enjoyment of life and fun.

Indulgent societies might be more receptive to new and innovative products and services that offer immediate pleasure and gratification through unconventional marketing strategies. In contrast, societies with low indulgence are more responsive to traditional marketing strategies with an emphasis on reliability and stability.

Core Principles of International Marketing – Chapter 3.5 by Babu John Mariadoss is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“2.5. In-depth Look: Hofstede’s Cultural Theory” in Strategic Project Management: Theory and Practice for Human Resource Professionals by Debra Patterson is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.