3.1 What is Culture

Case: Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins: Making Local Global

High-tech and digital news may dominate our attention globally, but no matter where you go, people still need to eat. Food is a key part of many cultures. It is part of the bonds of our childhood, creating warm memories of comfort food or favourite foods that continue to whet our appetites. So it’s no surprise that sugar and sweets are a key part of our food focus, no matter what the culture. Two of the most visible American exports are the twin brands of Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins.

Owned today by a consortium of private equity firms known as the Dunkin’ Brands, Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins have been sold globally for more than fifty years. Today, the firm has more than 14,800 points of distribution in forty-four countries with $6.9 billion in global sales.

After an eleven-year hiatus, Dunkin’ Donuts returned to Russia in 2010 with the opening of twenty new stores. Under a new partnership, “the planned store openings come 11 years after Dunkin’ Donuts pulled out of Russia, following three years of losses exacerbated by a rogue franchisee who sold liquor and meat pies alongside coffee and crullers” (Helliker, 2010). Each culture has different engrained habits, particularly in the choices of food and what foods are appropriate for what meals. The more globally aware businesses are mindful of these issues and monitor their overseas operations and partners. One of the key challenges for many companies operating globally with different resellers, franchisees, and wholly owned subsidiaries is the ability to control local operations.

This wasn’t the first time that Dunkin’ had encountered an overzealous local partner who tried to customize operations to meet local preferences and demands. In Indonesia in the 1990s, the company was surprised to find that local operators were sprinkling a mild, white cheese on a custard-filled donut. The company eventually approved the local customization since it was a huge success (Jenkins, 2010).

Dunkin’ Donuts and Baskin-Robbins have not always been owned by the same firm. They eventually came under one entity in the late 1980s—an entity that sought to leverage the two brands. One of the overall strategies was to have the morning market covered by Dunkin’ Donuts and the afternoon-snack market covered by Baskin-Robbins. It is a strategy that worked well in the United States and was one the company employed as it started operating and expanding in different countries. The company was initially unprepared for the wide range of local cultural preferences and habits that would culturally impact its business. In Russia, Japan, China, and most of Asia, donuts, if they were known at all, were regarded more as a sweet type of bakery treat, like an éclair or cream puff. Locals primarily purchased and consumed them at shopping malls as an “impulse purchase” afternoon-snack item and not as a breakfast food.

In fact, in China, there was no equivalent word for “donut” in Mandarin, and European-style baked pastries were not common outside the Shanghai and Hong Kong markets. To further complicate Dunkin’ Donuts’s entry into China, which took place initially in Beijing, the company name could not even be phonetically spelled in Chinese characters that made any sense, as Baskin-Robbins had been able to do in Taiwan. After extensive discussion and research, company executives decided that the best name and translation for Dunkin’ Donuts in China would read Sweet Sweet Ring in Chinese characters.

Local cultures also impacted flavours and preferences. For Baskin-Robbins, the flavour library is controlled in the United States, but local operators in each country have been the source of new flavour suggestions. In many cases, flavors that were customized for local cultures were added a decade later to the main menus in major markets, including the United States. Mango and green tea were early custom ice cream flavours in the 1990s for the Asian market. In Latin America, dulce de leche became a favourite flavor. Today, these flavors are staples of the North American flavour menu.

One flavour suggestion from Southeast Asia never quite made it onto the menu. The durian fruit is a favourite in parts of Southeast Asia, but it has a strong, pungent odour. Baskin-Robbins management was concerned that the strong odour would overwhelm factory operations. (The odour of the durian fruit is so strong that the fruit is often banned in upscale hotels in several Asian countries.) While the durian never became a flavour, the company did concede to making ice cream flavoured after the ube, a sweetened purple yam, for the Philippine market. It was already offered in Japan, and the company extended it to the Philippines. In Japan, sweet corn and red bean ice cream were approved for local sale and became hot sellers, but the two flavours never made it outside the country.

When reviewing local suggestions, management conducts a market analysis to determine if the global market for the flavour is large enough to justify the investment in research and development and eventual production. In addition to the market analysis, the company always has to make sure they have access to sourcing quality flavors and fruit. Mango proved to be a challenge, as finding the correct fruit puree differed by country or culture. Samples from India, Hawaii, Pakistan, Mexico, the Philippines, and Puerto Rico were taste-tested in the mainland United States. It seems that the mango is culturally regarded as a national treasure in every country where it is grown, and every country thinks its mango is the best. Eventually the company settled on one particular flavour of mango.

A challenging balance for Dunkin’ Brands is to enable local operators to customize flavours and food product offerings without diminishing the overall brand of the companies. Russians, for example, are largely unfamiliar with donuts, so Dunkin’ has created several items that specifically appeal to Russian flavor preferences for scalded cream and raspberry jam (Helliker, 2010). In some markets, one of the company’s brands may establish a market presence first. In Russia, the overall “Dunkin’ Brands already ranks as a dessert purveyor. Its Baskin-Robbins ice-cream chain boasts 143 shops there, making it the No. 2 Western restaurant brand by number of stores behind the hamburger chain McDonald’s Corp” (Helliker, 2010). The strength of the company’s ice cream brand is now enabling Dunkin’ Brands to promote the donut chain as well.

As the case about Dunkin’ Brands illustrates, local preferences, habits, values, and culture impact all aspects of doing business in a country. But what exactly do we mean by culture? Culture is different from personality. For our purposes here, let’s define personality as a person’s identity and unique physical, mental, emotional, and social characteristics (Dictionary.com, n.d.). No doubt one of the highest hurdles to cross-cultural understanding and effective relationships is our frequent inability to decipher the influence of culture from that of personality. Once we become culturally literate, we can more easily read individual personalities and their effect on our relationships.

So, What Is Culture, Anyway?

Culture in today’s context is different from the traditional, more singular definition, used particularly in Western languages, where the word often implies refinement. Culture is the beliefs, values, mind-sets, and practices of a group of people. It includes the behaviour pattern and norms of that group—the rules, the assumptions, the perceptions, and the logic and reasoning that are specific to a group. In essence, each of us is raised in a belief system that influences our individual perspectives to such a large degree that we can’t always account for, or even comprehend, its influence. We’re like other members of our culture—we’ve come to share a common idea of what’s appropriate and inappropriate.

Culture is really the collective programming of our minds from birth. It’s this collective programming that distinguishes one group of people from another. Much of the problem in any cross-cultural interaction stems from our expectations. The challenge is that whenever we deal with people from another culture—whether in our own country or globally—we expect people to behave as we do and for the same reasons. Culture awareness most commonly refers to having an understanding of another culture’s values and perspective. This does not mean automatic acceptance; it simply means understanding another culture’s mind-set and how its history, economy, and society have impacted what people think. Understanding so you can properly interpret someone’s words and actions means you can effectively interact with them.

When talking about culture, it’s important to understand that there really are no rights or wrongs. People’s value systems and reasoning are based on the teachings and experiences of their culture. Rights and wrongs then really become perceptions. Cross-cultural understanding requires that we reorient our mind-set and, most importantly, our expectations, in order to interpret the gestures, attitudes, and statements of the people we encounter. We reorient our mind-set, but we don’t necessarily change it.

There are a number of factors that constitute a culture—manners, mind-set, rituals, laws, ideas, and language, to name a few. To truly understand culture, you need to go beyond the lists of dos and don’ts, although those are important too. You need to understand what makes people tick and how, as a group, they have been influenced over time by historical, political, and social issues. Understanding the “why” behind culture is essential.

When trying to understand how cultures evolve, we look at the factors that help determine cultures and their values. In general, a value is defined as something that we prefer over something else—whether it’s a behaviour or a tangible item. Values are usually acquired early in life and are often nonrational—although we may believe that ours are actually quite rational. Our values are the key building blocks of our cultural orientation.

Odds are that each of us has been raised with a considerably different set of values from those of our colleagues and counterparts around the world. Exposure to a new culture may take all you’ve ever learned about what’s good and bad, just and unjust, and beautiful and ugly and stand it on its head.

Human nature is such that we see the world through our own cultural shades. Tucked in between the lines of our cultural laws is an unconscious bias that inhibits us from viewing other cultures objectively. Our judgments of people from other cultures will always be coloured by the frame of reference we’ve been taught. As we look at our own habits and perceptions, we need to think about the experiences that have blended together to impact our cultural frame of reference.

In coming to terms with cultural differences, we tend to employ generalizations. This isn’t necessarily bad. Generalizations can save us from sinking into what may be abstruse, esoteric aspects of a culture. However, recognize that cultures and values are not static entities. They’re constantly evolving—merging, interacting, drawing apart, and reforming. Around the world, values and cultures are evolving from generation to generation as people are influenced by things outside their culture. In modern times, media and technology have probably single-handedly impacted cultures the most in the shortest time period—giving people around the world instant glimpses into other cultures, for better or for worse. Recognizing this fluidity will help you avoid getting caught in outdated generalizations. It will also enable you to interpret local cues and customs and to better understand local cultures.

Understanding what we mean by culture and what the components of culture are will help us better interpret the impact on business at both the macro and micro levels. Confucius had this to say about cultural crossings: “Human beings draw close to one another by their common nature, but habits and customs keep them apart.”

Case: Student Perspective on Social and Cultural Environment

Born and raised in the Philippines with Filipino and Japanese parents, and now living in Canada – one of the most notable characteristics of us Filipinos is our strong family and community relationships. We keep our family ties strong and always show our respect to our elders by using the gesture “mano po”- which is to get the hand of the elder and put it onto your forehead. We even have endearments that are used to call older sisters and older brothers. “Ate” and “Kuya”. Quite similar to my Japanese roots as we use “Onee-san” and “Onii-san”. This is something that I noticed as one of the biggest cultural differences since my arrival here in Canada. I felt and observed that there is a strong individualism as opposed to the Philippines, where collectivism is highly practised. Here, people seem to go on in their own ways, while we would usually be involved in everyone’s businesses. Religious beliefs are also diverse as Canada has a very multicultural population, while in the Philippines, our beliefs are mostly centred on Catholicism.

Alliane Akiyama, October 2022

What Kinds of Culture Are There?

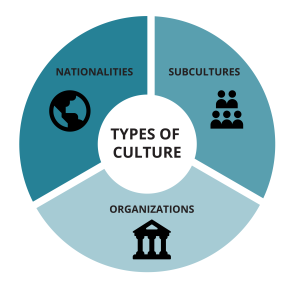

Political, economic, and social philosophies all impact the way people’s values are shaped. Our cultural base of reference—formed by our education, religion, or social structure—also impacts business interactions in critical ways. As we study cultures, it is very important to remember that all cultures are constantly evolving. When we say “cultural,” we don’t always just mean people from different countries. Every group of people has its own unique culture—that is, its own way of thinking, values, beliefs, and mind-sets. For our purposes in this chapter, we’ll focus on national and ethnic cultures, although there are subcultures within a country or ethnic group.

Precisely where a culture begins and ends can be murky. Some cultures fall within geographic boundaries; others, of course, overlap. Cultures within one border can turn up within other geographic boundaries looking dramatically different or pretty much the same. For example, Indians in India or Americans in the United States may communicate and interact differently from their countrymen who have been living outside their respective home countries for a few years.

The countries of the Indian subcontinent, for example, have close similarities. And cultures within one political border can turn up within other political boundaries looking pretty much the same, such as the Chinese culture in China and the overseas Chinese culture in countries around the world. We often think that cultures are defined by the country or nation, but that can be misleading because there are different cultural groups (as depicted in the preceding figure). These groups include nationalities; subcultures (gender, ethnicities, religions, generations, and even socioeconomic class); and organizations, including the workplace.

Nationalities

A national culture is—as it sounds—defined by its geographic and political boundaries and includes even regional cultures within a nation as well as among several neighbouring countries. What is important about nations is that boundaries have changed throughout history. These changes in what territory makes up a country and what the country is named impact the culture of each country.

In the past century alone, we have seen many changes as new nations emerged from the gradual dismantling of the British and Dutch empires at the turn of the 1900s. For example, today the physical territories that constitute the countries of India and Indonesia are far different than they were a hundred years ago. While it’s easy to forget that the British ran India for two hundred years and that the Dutch ran Indonesia for more than one hundred and fifty years, what is clearer is the impact of the British and the Dutch on the respective bureaucracies and business environments. The British and the Dutch were well known for establishing large government bureaucracies in the countries they controlled. Unlike the British colonial rulers in India, the Dutch did little to develop Indonesia’s infrastructure, civil service, or educational system. The British, on the other hand, tended to hire locals for administrative positions, thereby establishing a strong and well-educated Indian bureaucracy. Even though many businesspeople today complain that this Indian bureaucracy is too slow and focused on rules and regulations, the government infrastructure and English-language education system laid out by the British helped position India for its emergence as a strong high-tech economy.

Even within a national culture, there are often distinct regional cultures—the United States is a great example of diverse and distinct cultures all living within the same physical borders. In the United States, there’s a national culture embodied in the symbolic concept of “all-American” values and traits, but there are also other cultures based on geographically different regions—the South, Southwest, West Coast, East Coast, Northeast, Mid-Atlantic, and Midwest.

Subcultures

Many groups are defined by ethnicity, gender, generation, religion, or other characteristics with cultures that are unique to them. For example, the ethnic Chinese business community has a distinctive culture even though it may include Chinese businesspeople in several countries. This is particularly evident throughout Asia, as many people often refer to Chinese businesses as making up a single business community. The overseas Chinese business community tends to support one another and forge business bonds whether they are from Indonesia, Malaysia, Singapore, or other ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries. This group is perceived differently than Chinese from mainland China or Taiwan. Their common experience being a minority ethnic community with strong business interests has led to a shared understanding of how to quietly operate large businesses in countries. Just as in mainland China, guanxi, or “connections,” are essential to admission into this overseas Chinese business network. But once in the network, the Chinese tend to prefer doing business with one another and offer preferential pricing and other business services.

Organizations

Every organization has its own workplace culture, referred to as the organizational culture. This defines simple aspects such as how people dress (casual or formal), how they perceive and value employees, or how they make decisions (as a group or by the manager alone). When we talk about an entrepreneurial culture in a company, it might imply that the company encourages people to think creatively and respond to new ideas fairly quickly without a long internal approval process. One of the issues managers often have to consider when operating with colleagues, employees, or customers in other countries is how the local country’s culture will blend or contrast with the company’s culture.

Organizational Culture

For example, Apple, Google, and Microsoft all have distinct business cultures that are influenced both by their industries and by the types of technology-savvy employees that they hire, as well as by the personalities of their founders. When these firms operate in a country, they have to assess how new employees will fit their respective corporate cultures, which usually emphasize creativity, innovation, teamwork balanced with individual accomplishment, and a keen sense of privacy. Their global employees may appear relaxed in casual work clothes, but underneath there is often a fierce competitiveness. So how do these companies effectively hire in countries like Japan, where teamwork and following rules are more important than seeking new ways of doing things? This is an ongoing challenge that human resources (HR) departments continually seek to address.

Core Principles of International Marketing – Chapter 3,4 by Babu John Mariadoss is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.