14.1 The Internet

The internet is a network of networks—millions of them, actually. If the network at your university, your employer, or your home has internet access, it connects to an internet service provider (ISP). Many, but not all, ISPs are big telecommunications companies like Rogers Communications, Bell Canada, or Telus Inc . These providers connect to one another, exchanging traffic, and ensure your messages get to other computers that are online and willing to communicate with you.

The internet has no centre and no one owns it. That’s a good thing. The internet was designed to be redundant and fault-tolerant—meaning that if one network, connecting wire, or server stops working, everything else should keep on running. Rising from military research and work at educational institutions dating as far back as the 1960s, the internet really took off in the 1990s, when graphical web browsing was invented. Much of the internet’s operating infrastructure was transitioned to be supported by private firms rather than government grants. We will now explore this history in more detail.

History of the Internet

In the Beginning: ARPANET

The story of the internet, and networking in general, can be traced back to the late 1950s. The United States was in the depths of the Cold War with the USSR as each nation closely watched the other to determine which would gain a military or intelligence advantage. In 1957, the Soviets surprised the U.S. with the launch of Sputnik, propelling us into the space age. In response to Sputnik, the U.S. Government created the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA), whose initial role was to ensure that the U.S. was not surprised again. It was from ARPA, now called DARPA (Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), that the internet first sprang.

ARPA was the centre of computing research in the 1960s, but there was just one problem. Many of the computers could not communicate with each other. In 1968 ARPA sent out a request for proposals for a communication technology that would allow different computers located around the country to be integrated together into one network. Twelve companies responded to the request, and a company named Bolt, Beranek, and Newman (BBN) won the contract. They immediately began work and were able to complete the job just one year later.

ARPA Net 1969

Professor Len Kleinrock of UCLA along with a group of graduate students were the first to successfully send a transmission over the ARPANET. The event occurred on October 29, 1969 when they attempted to send the word “login” from their computer at UCLA to the Stanford Research Institute. The first four nodes were at UCLA, University of California, Stanford, and the University of Utah.

The Internet

Over the next decade, the ARPANET grew and gained popularity. During this time, other networks also came into existence. Different organizations were connected to different networks. This led to a problem. The networks could not communicate with each other. Each network used its own proprietary language, or protocol to send information back and forth. A protocol is the set of rules that govern how communications take place on a network. This problem was solved by the invention of the Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocol (TCP/IP). TCP/IP was designed to allow networks running on different protocols to have an intermediary protocol that would allow them to communicate. So as long as your network supported TCP/IP, you could communicate with all of the other networks running TCP/IP. TCP/IP quickly became the standard protocol and allowed networks to communicate with each other.

The 1980s witnessed a significant growth in internet usage. Internet access came primarily from government, academic, and research organizations. Much to the surprise of the engineers and developers, the early popularity of the internet was driven by the use of electronic mail. People connecting with people was the killer app for the internet.

The World Wide Web

Initially, internet use meant having to type commands, even including IP addresses, in order to access a web server. That all changed in 1990 when Tim Berners-Lee introduced his World Wide Web project which provided an easy way to navigate the internet through the use of hypertext. The World Wide Web gained even more steam in 1993 with the release of the Mosaic browser which allowed graphics and text to be combined as a way to present information and navigate the internet. Many times the terms “Internet” and “World Wide Web,” or even just “the web,” are used interchangeably. But really, they are not the same thing.

The Internet and the Web – What’s the Difference?

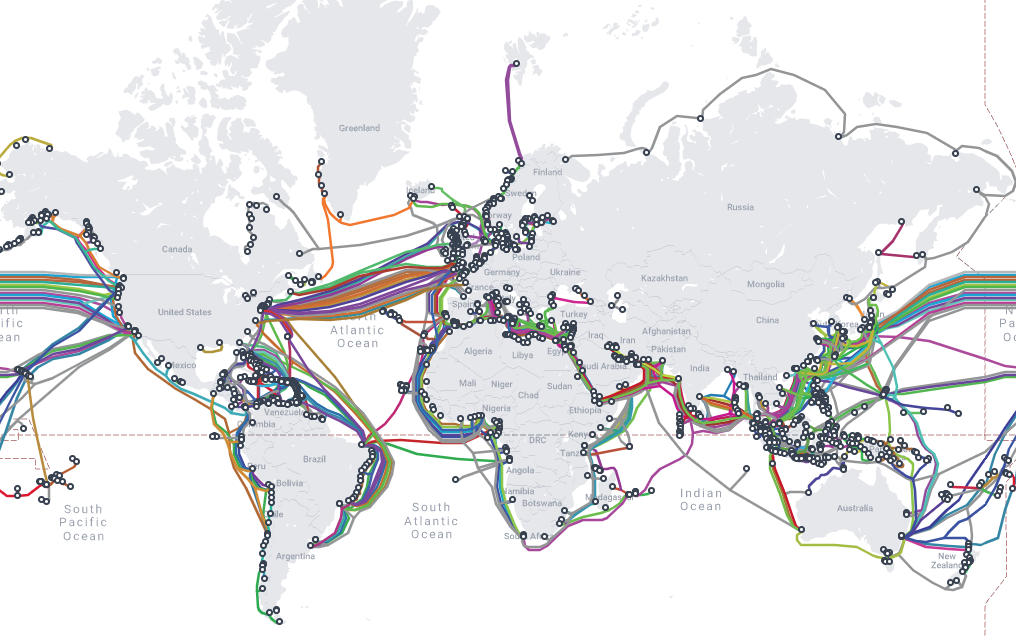

The internet is an interconnected network of networks. Services such as email, voice and video, file transfer, and the World Wide Web (the web for short) all run across the internet. The web is simply one part of the internet. It is made up of web servers that have HTML pages that are being viewed on devices with web browsers. To see an interactive map of the world’s major submarine cable systems go to TeleGeography’s Submarine Cable Map. A snapshot of the interactive map can be seen below.

The Dot-Com Bubble

In the 1980s and early 1990s, the internet was being managed by the National Science Foundation (NSF). The NSF had restricted commercial ventures on the internet, which meant that no one could buy or sell anything online. In 1991, the NSF transferred its role to three other organizations, thus getting the US government out of direct control over the internet and essentially opening up commerce online.

This new commercialization of the internet led to what is now known as the dot-com bubble. A frenzy of investment in new dot-com companies took place in the late 1990s with new tech companies issuing Initial Public Offerings (IPO) and heating up the stock market. This investment bubble was driven by the fact that investors knew that online commerce would change everything. Unfortunately, many of these new companies had poor business models and anemic financial statements showing little or no profit. In 2000 and 2001, the bubble burst and many of these new companies went out of business. Some companies survived, including Amazon (started in 1994) and eBay (1995). After the dot-com bubble burst, a new reality became clear. In order to succeed online, e-business companies would need to develop business models appropriate for the online environment.

The Generations of the Web

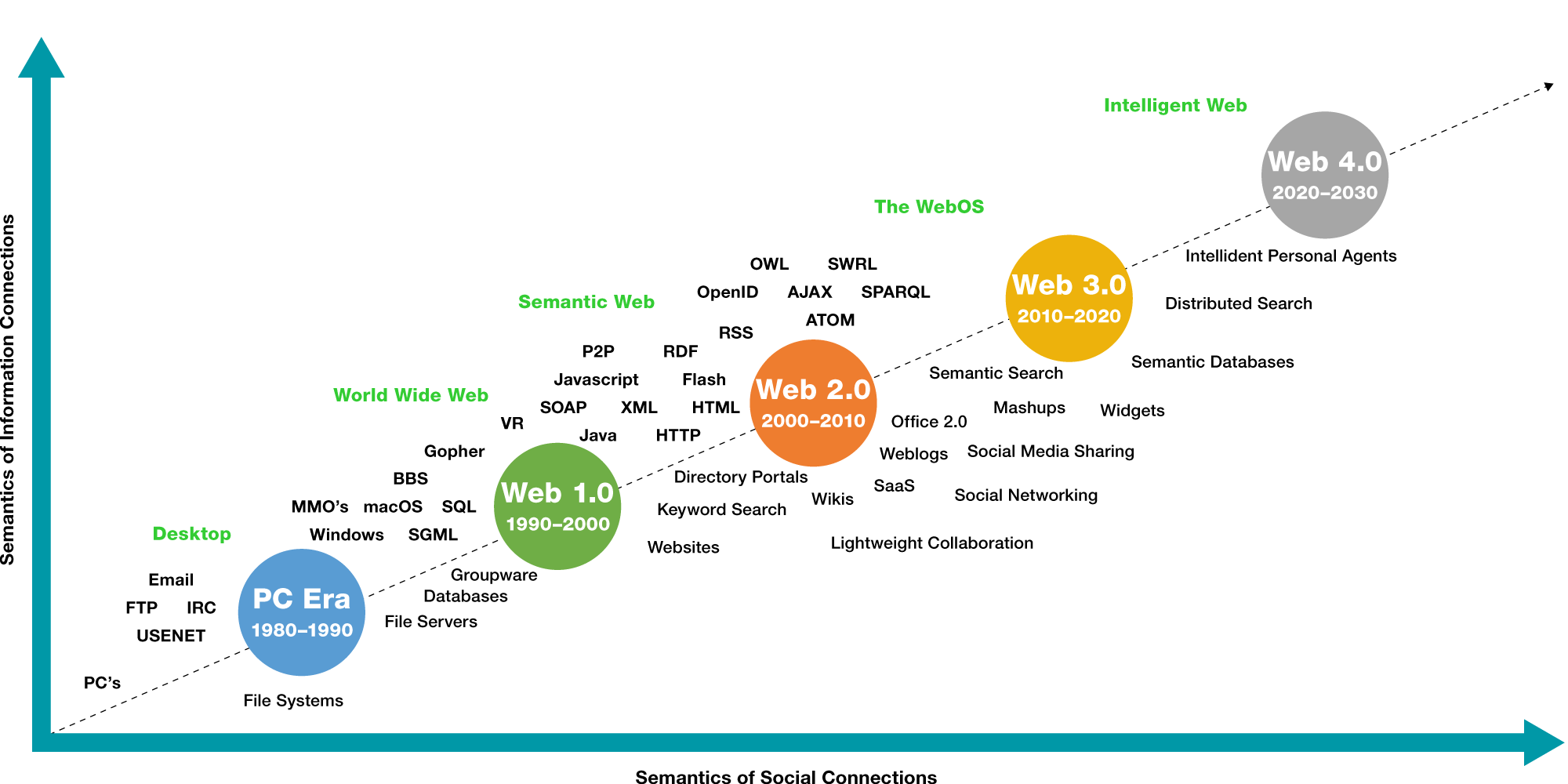

In the first few years of the web, creating and hosting a website required a specific set of knowledge. A person had to know how to set up a web server, get a domain name, create web pages in HTML, and troubleshoot various technical issues. Since then the web has evolved. This evolution has been referred to as different phases.

- Web 2.0 is also referred to as the social web and occurred between 2000-2010. During this time there was a shift from read only to read and write, which allowed individuals to be content creators. Social networking with apps such as Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and personal blogs have allowed people to express their own view points and share content.

- Web 3.0 is also referred to as the semantic web and is the time after 2010 when the web evolved again to allow individuals to read, write and execute. This means that the web is more intelligent and is able to interact with users. For example, algorithms that can personalize search results.

- Web 4.0 is the future of the web, which is referred to as the intelligent web and will involve the Internet of Things and connected devices.

There’s Another Internet?

Internet2 is a research network created by a consortium of research, academic, industry, and government firms. These organizations have collectively set up a high-performance network running at speeds of up to one hundred gigabits per second to support and experiment with demanding applications. Examples include high-quality video conferencing; high-reliability, high-bandwidth imaging for the medical field; and applications that share huge data sets among researchers.

Information Systems for Business and Beyond: 6.4 by Shauna Roch; James Fowler; Barbara Smith; and David Bourgeois is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.