6.4 – Immigration

Learning Objectives

- Discuss the economic implications of immigration

Most Americans would be outraged if a law prevented them from moving to another city or another state. However, when the conversation turns to crossing national borders and are about other people arriving in the United States, laws preventing such movement often seem more reasonable. Some of the tensions over immigration stem from worries over how it might affect a country’s culture, including differences in language, and patterns of family, authority, or gender relationships. Economics does not have much to say about such cultural issues. Some of the worries about immigration do, however, have to do with its effects on wages and income levels, and how it affects government taxes and spending. On those topics, economists have insights and research to offer.

Historical Patterns of Immigration

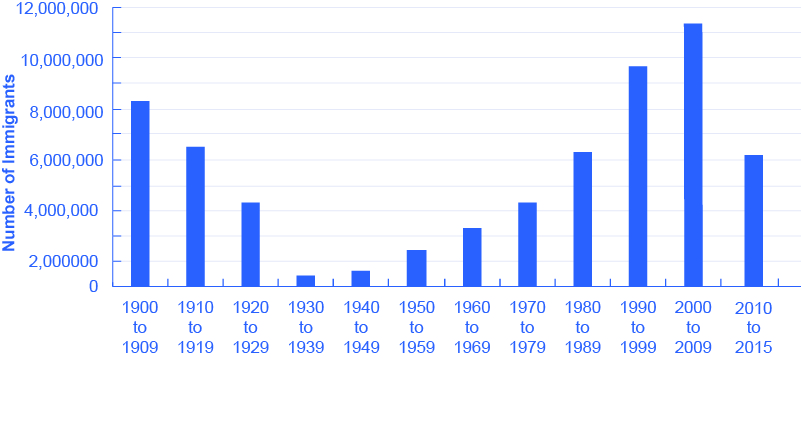

Supporters and opponents of immigration look at the same data and see different patterns. Those who express concern about immigration levels to the United States point to graphics like Figure 1 which shows total inflows of immigrants decade by decade through the twentieth century. Clearly, the level of immigration has been high and rising in recent years, reaching and exceeding the towering levels of the early twentieth century. However, those who are less worried about immigration point out that the high immigration levels of the early twentieth century happened when total population was much lower. Since the U.S. population roughly tripled during the twentieth century, the seemingly high levels in immigration in the 1990s and 2000s look relatively smaller when they are divided by the population.

From where have the immigrants come? Immigrants from Europe were more than 90% of the total in the first decade of the twentieth century, but less than 20% of the total by the end of the century. By the 2000s, about half of U.S. immigration came from the rest of the Americas, especially Mexico, and about a quarter came from various countries in Asia.

Economic Effects of Immigration

A surge of immigration can affect the economy in a number of different ways. In this section, we will consider how immigrants might benefit the rest of the economy, how they might affect wage levels, and how they might affect government spending at the federal and local level.

To understand the economic consequences of immigration, consider the following scenario. Imagine that the immigrants entering the United States matched the existing U.S. population in age range, education, skill levels, family size, and occupations. How would immigration of this type affect the rest of the U.S. economy? Immigrants themselves would be much better off, because their standard of living would be higher in the United States. Immigrants would contribute to both increased production and increased consumption. Given enough time for adjustment, the range of jobs performed, income earned, taxes paid, and public services needed would not be much affected by this kind of immigration. It would be as if the population simply increased a little.

Now, consider the reality of recent immigration to the United States. Immigrants are not identical to the rest of the U.S. population. About one-third of immigrants over the age of 25 lack a high school diploma. As a result, many of the recent immigrants end up in jobs like restaurant and hotel work, lawn care, and janitorial work. This kind of immigration represents a shift to the right in the supply of unskilled labour for a number of jobs, which will lead to lower wages for these jobs. The middle- and upper-income households that purchase the services of these unskilled workers will benefit from these lower wages. However, low-skilled U.S. workers who must compete with low-skilled immigrants for jobs will tend to suffer from immigration.

The difficult policy questions about immigration are not so much about the overall gains to the rest of the economy, which seem to be real but small in the context of the U.S. economy, as they are about the disruptive effects of immigration in specific labour markets. One disruptive effect, as we noted, is that immigration weighted toward low-skill workers tends to reduce wages for domestic low-skill workers. A study by Michael S. Clune found that for each 10% rise in the number of employed immigrants with no more than a high school diploma in the labour market, high school students reduced their annual number of hours worked by 3%. The effects on wages of low-skill workers are not large—perhaps in the range of decline of about 1%. These effects are likely kept low, in part, because of the legal floor of federal and state minimum wage laws. In addition, immigrants are also thought to contribute to increased demand for local goods and services which can stimulate the local low skilled labour market. It is also possible that employers, in the face of abundant low-skill workers may choose production processes which are more labour intensive than otherwise would have been. These various factors would explain the small negative wage effect that the native low-skill workers observed as a result of immigration.

Another potential disruptive effect is the impact on state and local government budgets. Many of the costs imposed by immigrants are costs that arise in state-run programs, like the cost of public schooling and of welfare benefits. However, many of the taxes that immigrants pay are federal taxes like income taxes and Social Security taxes. Many immigrants do not own property (such as homes and cars), so they do not pay property taxes, which are one of the main sources of state and local tax revenue. However, they do pay sales taxes, which are state and local, and the landlords of property they rent pay property taxes. According to the nonprofit Rand Corporation, the effects of immigration on taxes are generally positive at the federal level, but they are negative at the state and local levels in places where there are many low-skilled immigrants.

Proposals for Immigration Reform

The Congressional Jordan Commission of the 1990s proposed reducing overall levels of immigration and refocusing U.S. immigration policy to give priority to immigrants with higher skill levels. In the labour market, focusing on high-skilled immigrants would help prevent any negative effects on low-skilled workers’ wages. For government budgets, higher-skilled workers find jobs more quickly, earn higher wages, and pay more in taxes. Several other immigration-friendly countries, notably Canada and Australia, have immigration systems where those with high levels of education or job skills have a much better chance of obtaining permission to immigrate. For the United States, high tech companies regularly ask for a more lenient immigration policy to admit a greater quantity of highly skilled workers under the H1B visa program.

The Obama Administration proposed the so-called “DREAM Act” legislation, which would have offered a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants brought to the United States before the age of 16. Despite bipartisan support, the legislation failed to pass at the federal level. However, some state legislatures, such as California, have passed their own Dream Acts.

Between its plans for a border wall, increased deportation of undocumented immigrants, and even reductions in the number of highly skilled legal H1B immigrants, the Trump Administration has a much less positive approach to immigration. Most economists, whether conservative or liberal, believe that while immigration harms some domestic workers, the benefits to the nation exceed the costs. However, given the Trump Administration’s opposition, any significant immigration reform is likely on hold.

Watch It!

Watch The economics of immigration: Crash Course economics #33 (11 mins) on YouTube for a comprehensive overview on the economics of immigration.

Video Source: CrashCourse. (2016, May 18). The economics of immigration: Crash Course economics #33 [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/4XQXiCLzyAw

Try It

Try It – Text version

- Which of the following economic implications of immigration is not correct?

- Typically, when immigration increases, households pay less for projects involving unskilled labor and low-skilled U.S workers end up competing with low-skilled immigrants for these jobs.

- Immigration can benefit the local economy.

- An increase in immigration tends to impact on state and local government budgets by decreasing the use of resources and entitlement programs.

Check your Answer: [1]

Activity source: “Immigration” In Micoreconomics by LumenLearning, licensed under CC BY 4.0. / Converted to H5P and text.

Attribution

Except where otherwise noted, this chapter is adapted from “Immigration” In Micoreconomics by LumenLearning, licensed under CC BY 4.0. A derivative of “Immigration” In Principles of Economics 2e. by Steven A. Greenlaw and David Shapiro (OpenStax), licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Access for free at Principles of Microeconomics 2e

References

U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2012, September). Table 1. Persons obtaining legal permanent resident status: fiscal years 1820 to 2011 [2011 Yearbook of Immigration Statistics]. https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ois_yb_2011.pdf

Media Attributions

- Figure © Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro (OpenStax) is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

- 1. c) Correct. A potential disruptive effect to increased immigration is the impact on state and local government budgets. Many of the costs imposed by immigrants are costs that arise in state-run programs, like the cost of public schooling and of welfare benefits. ↵