8.5 – What Causes Changes in Unemployment over the Long Run

Learning Objectives

- Explain frictional and structural unemployment

- Assess relationships between the natural rate of employment and potential real GDP, productivity, and public policy

- Identify recent patterns in the natural rate of employment

- Propose ways to combat unemployment

Cyclical unemployment explains why unemployment rises during a recession and falls during an economic expansion, but what explains the remaining level of unemployment even in good economic times? Why is the unemployment rate never zero? Even when the U.S. economy is growing strongly, the unemployment rate only rarely dips as low as 4%. Moreover, the discussion earlier in this chapter pointed out that unemployment rates in many European countries like Italy, France, and Germany have often been remarkably high at various times in the last few decades. Why does some level of unemployment persist even when economies are growing strongly? Why are unemployment rates continually higher in certain economies, through good economic years and bad? Economists have a term to describe the remaining level of unemployment that occurs even when the economy is healthy: they call it the natural rate of unemployment.

The Long Run: The Natural Rate of Unemployment

The natural rate of unemployment is not “natural” in the sense that water freezes at 32 degrees Fahrenheit or boils at 212 degrees Fahrenheit. It is not a physical and unchanging law of nature. Instead, it is only the “natural” rate because it is the unemployment rate that would result from the combination of economic, social, and political factors that exist at a time—assuming the economy was neither booming nor in recession. These forces include the usual pattern of companies expanding and contracting their workforces in a dynamic economy, social and economic forces that affect the labour market, or public policies that affect either the eagerness of people to work or the willingness of businesses to hire. Let’s discuss these factors in more detail.

Frictional Unemployment

In a market economy, some companies are always going broke for a variety of reasons: old technology; poor management; good management that happened to make bad decisions; shifts in tastes of consumers so that less of the firm’s product is desired; a large customer who went broke; or tough domestic or foreign competitors. Conversely, other companies will be doing very well for just the opposite reasons and looking to hire more employees. In a perfect world, all of those who lost jobs would immediately find new ones. However, in the real world, even if the number of job seekers is equal to the number of job vacancies, it takes time to find out about new jobs, to interview and figure out if the new job is a good match, or perhaps to sell a house and buy another in proximity to a new job. Economists call the unemployment that occurs in the meantime, as workers move between jobs, frictional unemployment. Frictional unemployment is not inherently a bad thing. It takes time on part of both the employer and the individual to match those looking for employment with the correct job openings. For individuals and companies to be successful and productive, you want people to find the job for which they are best suited, not just the first job offered.

In the mid-2000s, before the 2008–2009 recession, it was true that about 7% of U.S. workers saw their jobs disappear in any three-month period. However, in periods of economic growth, these destroyed jobs are counterbalanced for the economy as a whole by a larger number of jobs created. In 2005, for example, there were typically about 7.5 million unemployed people at any given time in the U.S. economy. Even though about two-thirds of those unemployed people found a job in 14 weeks or fewer, the unemployment rate did not change much during the year, because those who found new jobs were largely offset by others who lost jobs.

Of course, it would be preferable if people who were losing jobs could immediately and easily move into newly created jobs, but in the real world, that is not possible. Someone who is laid off by a textile mill in South Carolina cannot turn around and immediately start working for a textile mill in California. Instead, the adjustment process happens in ripples. Some people find new jobs near their old ones, while others find that they must move to new locations. Some people can do a very similar job with a different company, while others must start new career paths. Some people may be near retirement and decide to look only for part-time work, while others want an employer that offers a long-term career path. The frictional unemployment that results from people moving between jobs in a dynamic economy may account for one to two percentage points of total unemployment.

The level of frictional unemployment will depend on how easy it is for workers to learn about alternative jobs, which may reflect the ease of communications about job prospects in the economy. The extent of frictional unemployment will also depend to some extent on how willing people are to move to new areas to find jobs—which in turn may depend on history and culture.

Frictional unemployment and the natural rate of unemployment also seem to depend on the age distribution of the population. Figure 8.3a (b) showed that unemployment rates are typically lower for people between 25–54 years of age or aged 55 and over than they are for those who are younger. “Prime-age workers,” as those in the 25–54 age bracket are sometimes called, are typically at a place in their lives when they want to have a job and income arriving at all times. In addition, older workers who lose jobs may prefer to opt for retirement. By contrast, it is likely that a relatively high proportion of those who are under 25 will be trying out jobs and life options, and this leads to greater job mobility and hence higher frictional unemployment. Thus, a society with a relatively high proportion of young workers, like the U.S. beginning in the mid-1960s when Baby Boomers began entering the labour market, will tend to have a higher unemployment rate than a society with a higher proportion of its workers in older ages.

Structural Unemployment

Another factor that influences the natural rate of unemployment is the amount of structural unemployment. The structurally unemployed are individuals who have no jobs because they lack skills valued by the labour market, either because demand has shifted away from the skills they do have, or because they never learned any skills. An example of the former would be the unemployment among aerospace engineers after the U.S. space program downsized in the 1970s. An example of the latter would be high school dropouts.

Some people worry that technology causes structural unemployment. In the past, new technologies have put lower skilled employees out of work, but at the same time they create demand for higher skilled workers to use the new technologies. Education seems to be the key in minimizing the amount of structural unemployment. Individuals who have degrees can be retrained if they become structurally unemployed. For people with no skills and little education, that option is more limited.

Natural Unemployment and Potential Real GDP

The natural unemployment rate is related to two other important concepts: full employment and potential real GDP. Economists consider the economy to be at full employment when the actual unemployment rate is equal to the natural unemployment rate. When the economy is at full employment, real GDP is equal to potential real GDP. By contrast, when the economy is below full employment, the unemployment rate is greater than the natural unemployment rate and real GDP is less than potential. Finally, when the economy is above full employment, then the unemployment rate is less than the natural unemployment rate and real GDP is greater than potential. Operating above potential is only possible for a short while, since it is analogous to all workers working overtime.

Productivity Shifts and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Unexpected shifts in productivity can have a powerful effect on the natural rate of unemployment. Over time, workers’ productivity determines the level of wages in an economy. After all, if a business paid workers more than could be justified by their productivity, the business will ultimately lose money and go bankrupt. Conversely, if a business tries to pay workers less than their productivity then, in a competitive labour market, other businesses will find it worthwhile to hire away those workers and pay them more.

However, adjustments of wages to productivity levels will not happen quickly or smoothly. Employers typically review wages only once or twice a year. In many modern jobs, it is difficult to measure productivity at the individual level. For example, how precisely would one measure the quantity produced by an accountant who is one of many people working in the tax department of a large corporation? Because productivity is difficult to observe, employers often determine wage increases based on recent experience with productivity. If productivity has been rising at, say, 2% per year, then wages rise at that level as well. However, when productivity changes unexpectedly, it can affect the natural rate of unemployment for a time.

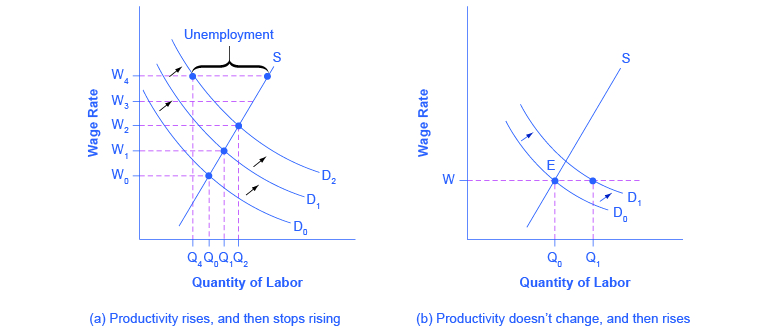

The U.S. economy in the 1970s and 1990s provides two vivid examples of this process. In the 1970s, productivity growth slowed down unexpectedly. For example, output per hour of U.S. workers in the business sector increased at an annual rate of 3.3% per year from 1960 to 1973, but only 0.8% from 1973 to 1982. Figure 8.5a (a) illustrates the situation where the demand for labour—that is, the quantity of labour that business is willing to hire at any given wage—has been shifting out a little each year because of rising productivity, from D0 to D1 to D2. As a result, equilibrium wages have been rising each year from W0 to W1 to W2. However, when productivity unexpectedly slows down, the pattern of wage increases does not adjust right away. Wages keep rising each year from W2 to W3 to W4, but the demand for labour is no longer shifting up. A gap opens where the quantity of labour supplied at wage level W4 is greater than the quantity demanded. The natural rate of unemployment rises. In the aftermath of this unexpectedly low productivity in the 1970s, the national unemployment rate did not fall below 7% from May, 1980 until 1986. Over time, the rise in wages will adjust to match the slower gains in productivity, and the unemployment rate will ease back down, but this process may take years.

The late 1990s provide an opposite example: instead of the surprise decline in productivity that occurred in the 1970s, productivity unexpectedly rose in the mid-1990s. The annual growth rate of real output per hour of labour increased from 1.7% from 1980–1995, to an annual rate of 2.6% from 1995–2001. Let’s simplify the situation a bit, so that the economic lesson of the story is easier to see graphically, and say that productivity had not been increasing at all in earlier years, so the intersection of the labour market was at point E in Figure 8.5a (b), where the demand curve for labour (D0) intersects the supply curve for labour. As a result, real wages were not increasing. Now, productivity jumps upward, which shifts the demand for labour out to the right, from D0 to D1. At least for a time, however, wages are still set according to the earlier expectations of no productivity growth, so wages do not rise. The result is that at the prevailing wage level (W), the quantity of labour demanded (Qd) will for a time exceed the quantity of labour supplied (Qs), and unemployment will be very low—actually below the natural level of unemployment for a time. This pattern of unexpectedly high productivity helps to explain why the unemployment rate stayed below 4.5%—quite a low level by historical standards—from 1998 until after the U.S. economy had entered a recession in 2001.

Levels of unemployment will tend to be somewhat higher on average when productivity is unexpectedly low, and conversely, will tend to be somewhat lower on average when productivity is unexpectedly high. However, over time, wages do eventually adjust to reflect productivity levels.

Public Policy and the Natural Rate of Unemployment

Public policy can also have a powerful effect on the natural rate of unemployment. On the supply side of the labour market, public policies to assist the unemployed can affect how eager people are to find work. For example, if a worker who loses a job is guaranteed a generous package of unemployment insurance, welfare benefits, food stamps, and government medical benefits, then the opportunity cost of unemployment is lower and that worker will be less eager to seek a new job.

What seems to matter most is not just the amount of these benefits, but how long they last. A society that provides generous help for the unemployed that cuts off after, say, six months, may provide less of an incentive for unemployment than a society that provides less generous help that lasts for several years. Conversely, government assistance for job search or retraining can in some cases encourage people back to work sooner. See the Clear it Up to learn how the U.S. handles unemployment insurance.

Link It Up

For an explanation of exactly who is eligible for unemployment benefits take a look at The Impacts of Unemployment Benefits on Job Match Quality and Labour Market Functioning [New Tab].

On the demand side of the labour market, government rules, social institutions, and the presence of unions can affect the willingness of firms to hire. For example, if a government makes it hard for businesses to start up or to expand, by wrapping new businesses in bureaucratic red tape, then businesses will become more discouraged about hiring. Government regulations can make it harder to start a business by requiring that a new business obtain many permits and pay many fees, or by restricting the types and quality of products that a company can sell. Other government regulations, like zoning laws, may limit where companies can conduct business, or whether businesses are allowed to be open during evenings or on Sunday.

Whatever defenses may be offered for such laws in terms of social value—like the value some Christians place on not working on Sunday, or Orthodox Jews or highly observant Muslims on Saturday—these kinds of restrictions impose a barrier between some willing workers and other willing employers, and thus contribute to a higher natural rate of unemployment. Similarly, if government makes it difficult to fire or lay off workers, businesses may react by trying not to hire more workers than strictly necessary—since laying these workers off would be costly and difficult. High minimum wages may discourage businesses from hiring low-skill workers. Government rules may encourage and support powerful unions, which can then push up wages for union workers, but at a cost of discouraging businesses from hiring those workers.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment in Recent Years

The underlying economic, social, and political factors that determine the natural rate of unemployment can change over time, which means that the natural rate of unemployment can change over time, too.

Estimates by economists of the natural rate of unemployment in the U.S. economy in the early 2000s run at about 4.5 to 5.5%. This is a lower estimate than earlier. We outline three of the common reasons that economists propose for this change below.

- The internet has provided a remarkable new tool through which job seekers can find out about jobs at different companies and can make contact with relative ease. An internet search is far easier than trying to find a list of local employers and then hunting up phone numbers for all of their human resources departments, and requesting a list of jobs and application forms. Social networking sites such as LinkedIn have changed how people find work as well.

- The growth of the temporary worker industry has probably helped to reduce the natural rate of unemployment. In the early 1980s, only about 0.5% of all workers held jobs through temp agencies. By the early 2000s, the figure had risen above 2%. Temp agencies can provide jobs for workers while they are looking for permanent work. They can also serve as a clearinghouse, helping workers find out about jobs with certain employers and getting a tryout with the employer. For many workers, a temp job is a stepping-stone to a permanent job that they might not have heard about or obtained any other way, so the growth of temp jobs will also tend to reduce frictional unemployment.

- The aging of the “baby boom generation”—the especially large generation of Americans born between 1946 and 1964—meant that the proportion of young workers in the economy was relatively high in the 1970s, as the boomers entered the labour market, but is relatively low today. As we noted earlier, middle-aged and older workers are far more likely to experience low unemployment than younger workers, a factor that tends to reduce the natural rate of unemployment as the baby boomers age.

The combined result of these factors is that the natural rate of unemployment was on average lower in the 1990s and the early 2000s than in the 1980s. The 2008–2009 Great Recession pushed monthly unemployment rates up to 10% in late 2009. However, even at that time, the Congressional Budget Office was forecasting that by 2015, unemployment rates would fall back to about 5%. During the last four months of 2015 the unemployment rate held steady at 5.0%. Throughout 2016 and up through January 2017, the unemployment rate has remained at or slightly below 5%. As of the first quarter of 2017, the Congressional Budget Office estimates the natural rate to be 4.74%, and the measured unemployment rate for January 2017 is 4.8%.

The Natural Rate of Unemployment in Europe

By the standards of other high-income economies, the natural rate of unemployment in the U.S. economy appears relatively low. Through good economic years and bad, many European economies have had unemployment rates hovering near 10%, or even higher, since the 1970s. European rates of unemployment have been higher not because recessions in Europe have been deeper, but rather because the conditions underlying supply and demand for labour have been different in Europe, in a way that has created a much higher natural rate of unemployment.

Many European countries have a combination of generous welfare and unemployment benefits, together with nests of rules that impose additional costs on businesses when they hire. In addition, many countries have laws that require firms to give workers months of notice before laying them off and to provide substantial severance or retraining packages after laying them off. The legally required notice before laying off a worker can be more than three months in Spain, Germany, Denmark, and Belgium, and the legally required severance package can be as high as a year’s salary or more in Austria, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Greece. Such laws will surely discourage laying off or firing current workers. However, when companies know that it will be difficult to fire or lay off workers, they also become hesitant about hiring in the first place.

We can attribute the typically higher levels of unemployment in many European countries in recent years, which have prevailed even when economies are growing at a solid pace, to the fact that the sorts of laws and regulations that lead to a high natural rate of unemployment are much more prevalent in Europe than in the United States.

A Preview of Policies to Fight Unemployment

The remedy for unemployment will depend on the diagnosis. Cyclical unemployment is a short-term problem, caused because the economy is in a recession. Thus, the preferred solution will be to avoid or minimize recessions. Governments can enact this policy by stimulating the overall buying power in the economy, so that firms perceive that sales and profits are possible, which makes them eager to hire.

Dealing with the natural rate of unemployment is trickier. In a market-oriented economy, firms will hire and fire workers. Governments cannot control this. Furthermore, the evolving age structure of the economy’s population, or unexpected shifts in productivity are beyond a government’s control and, will affect the natural rate of unemployment for a time. However, as the example of high ongoing unemployment rates for many European countries illustrates, government policy clearly can affect the natural rate of unemployment that will persist even when GDP is growing.

When a government enacts policies that will affect workers or employers, it must examine how these policies will affect the information and incentives employees and employers have to find one another. For example, the government may have a role to play in helping some of the unemployed with job searches. Governments may need to rethink the design of their programs that offer assistance to unemployed workers and protections to employed workers so that they will not unduly discourage the supply of labour. Similarly, governments may need to reassess rules that make it difficult for businesses to begin or to expand so that they will not unduly discourage the demand for labour. The message is not that governments should repeal all laws affecting labour markets, but only that when they enact such laws, a society that cares about unemployment will need to consider the tradeoffs involved.

Bring It Home

Unemployment and the Great Recession

In the review of unemployment during and after the Great Recession at the outset of this chapter, we noted that unemployment tends to be a lagging indicator of business activity. This has historically been the case, and it is evident for all recessions that have taken place since the end of World War II. In brief, this results from the costs to employers of recruitment, hiring, and training workers. Those costs represent investments by firms in their work forces.

At the outset of a recession, when a firm realizes that demand for its product or service is not as strong as anticipated, it has an incentive to lay off workers. However, doing so runs the risk of losing those workers, and if the weak demand proves to be only temporary, the firm will be obliged to recruit, hire, and train new workers. Thus, firms tend to retain workers initially in a downturn. Similarly, as business begins to pick up when a recession is over, firms are not sure if the improvement will last. Rather than incur the costs of hiring and training new workers, they will wait, and perhaps resort to overtime work for existing workers, until they are confident that the recession is over.

Another point that we noted at the outset is that the duration of recoveries in employment following recessions has been longer following the last three recessions (going back to the early 1990s) than previously. Nir Jaimovich and Henry Siu have argued that these “jobless recoveries” are a consequence of job polarization – the disappearance of employment opportunities focused on “routine” tasks. Job polarization refers to the increasing concentration of employment in the highest- and lowest-wage occupations, as jobs in middle-skill occupations disappear. Job polarization is an outcome of technological progress in robotics, computing, and information and communication technology. The result of this progress is a decline in demand for labour in occupations that perform “routine” tasks – tasks that are limited in scope and can be performed by following a well-defined set of procedures – and hence a decline in the share of total employment that is composed of routine occupations. Jaimovich and Siu have shown that job polarization characterizes the aftermath of the last three recessions, and this appears to be responsible for the jobless recoveries.

Key Concepts and Summary

The natural rate of unemployment is the rate of unemployment that the economic, social, and political forces in the economy would cause even when the economy is not in a recession. These factors include the frictional unemployment that occurs when people either choose to change jobs or are put out of work for a time by the shifts of a dynamic and changing economy. They also include any laws concerning conditions of hiring and firing that have the undesired side effect of discouraging job formation. They also include structural unemployment, which occurs when demand shifts permanently away from a certain type of job skill.

Attribution

Original Source Chapter References

Bureau of Labor Statistics. Labor Force Statistics from the Current Population Survey. Accessed March 6, 2015 http://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS14000000.

Cappelli, P. (20 June 2012). “Why Good People Can’t Get Jobs: Chasing After the Purple Squirrel.” http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article.cfm?articleid=3027.

Media Attributions

- Figure © Steven A. Greenlaw & David Shapiro (OpenStax), is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license

The unemployment rate that would exist in a growing and healthy economy from the combination of economic, social, and political factors that exist at a given time

Unemployment that occurs because individuals lack skills valued by employers