Fertility depends on three things: opportunities for intentional or unintentional reproduction; intentions around family size; and ability to carry out those intentions.

In almost all cultures, the parents of a young man or woman traditionally have arranged the marriage, encouraged the couple to have children, and supported them with housing and childcare. A woman may have been compelled to have more children by her husband or in-laws.

Today, western young people typically choose their own partners, choose their desired number of children, and find their own housing and childcare arrangements. Women typically have veto power when it comes to engaging in sexual intercourse or having an additional child. Across the world, greater personal freedom, greater social tolerance of non-traditional family arrangements, and advancing medical technology are uniting to make it possible for people to have as many or as few children as they wish.

Opportunities

Fertility rates are higher when people have more opportunities to meet and mingle. Factors which influence opportunities to meet and mingle include the degree of social isolation; the sex ratio; the usual age at marriage or cohabitation; degree of absence of spouse; likelihood of bereavement, separation, or divorce; and time between unions (if separation or widowhood occur).

Social and religious norms, income, geography, and political crises influence the opportunity to partner. The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020+ greatly interfered with the ability of people to meet partners. Generally speaking, prosperity, peace, urbanization, and secularization mean greater opportunities for partnering and conception.

Intentions

Sadly, intentions around sex and fertility are sometimes violated by acts of rape. On a lighter note, we sometimes succumb to consensual passion and forget our intentions.

For the most part, people in many nations today have quite a bit of freedom when it comes to having children. Our target number of children depends on personal preferences, family/social/religious norms, and economic considerations. We’ll discuss the economic considerations in detail later in this chapter.

The target number of children may change as parents raise their first or subsequent children, and as life experiences impact the family. The desired number of children also depends on a person’s experience of childhood and on their notion of what the future holds.

When infants or children die, the family may try to conceive more children.

Sometimes a family has more children in order to achieve a target number of children with particular characteristics. In the past, one had to “keep trying” until one had the desired number of boys, girls, healthy children etc. Now genetic testing in utero is making selection easier, and reducing overall fertility. (More on that in our next chapter and in our chapter on son preference.)

Ability to achieve intentions

Once people have an idea of how many children they would like to have and when they would like to have them, they can begin to plan accordingly. Our plans do not always work out the way we expect.

Conception cannot be taken for granted. The age of the parents, breastfeeding, malnutrition, disease, excessive exercise, lack of exercise, and stress can interfere with conception and pregnancy. If conception and pregnancy are not successful, the would-be parent(s) may turn to medical treatments to enhance fertility, in vitro fertilization[1], or hiring a surrogate mother[2]. These are usually expensive options.

Adoption and fostering are alternative ways to build a family. Adoption and fostering do not contribute to “fertility” because they do not create new individuals, but adoption and fostering do build families and contribute to a healthier, more emotionally resilient population.

Economic prosperity makes it easier for people to manage their health and to access assistive reproductive technologies. But it also helps people afford birth control, which has the opposite effect on fertility.

Birth control is about preventing live births, and it includes abstinence, contraception, abortion, and sterilization.

Infanticide after a birth has been recorded, neglect, and abandonment may be forms of delayed birth control, but they do not decrease fertility; they increase mortality.

Some potential parents, while wishing to reduce family size, reject some or all methods of birth control for moral, religious, or medical reasons. Other potential parents are uninformed about birth control methods, or find birth control unavailable or prohibitively expensive.

Does rising income lead to more use of birth control? Or does it tend to help people increase the size of their families? It all depends on what people want, and for a few centuries people have tended to want to reduce family size.

Even before modern birth control methods were available, in the days when contraception was limited to herbal concoctions, abstinence, and withdrawal, people were able to reduce their family size significantly. For example, births per year per married woman in France fell from 0.775 in 1740 to 0.410 in 1891 and then to an even lower 0.273 in 1931 (Wrigley, 1985).

Scholars collaborating on Princeton University’s European Fertility History Project (1971- 1986) concluded that secularization, more than anything else, was associated with falling fertility rates. Secularization meant that people wanted smaller families, and they achieved smaller families even without a lot of money or modern technology. Fertility fell in European provinces even where infant mortality was still high, and where income per person had not yet risen appreciably, if those provinces were integrated with more secularized provinces sharing the same language and culture.

Secularization of a culture occurs as society organizes itself along non-religious lines. The government, the courts, schools, and other institutions adopt a neutral religious stance. Secularization encourages education and personal decision-making without reference to religious authority. It encourages individualism, sometimes at the expense of community. Secularization, affecting intentions around fertility, has likely been the strongest driver of fertility decline.

People who delay fertility are sometimes unable to achieve their desired number of children. This is called the Fertility Trap. This can happen on an individual level or at the level of society as a whole. An individual may delay fertility, only to realize that they are no longer able to reproduce. A society may discourage fertility, and then later, when it seeks to encourage fertility, it may find that people are not used to having large families anymore. Social norms and material realities may have changed in such a way that having large families has become difficult.

People who delay fertility are sometimes unable to achieve their desired number of children. This is called the Fertility Trap. This can happen on an individual level or at the level of society as a whole. An individual may delay fertility, only to realize that they are no longer able to reproduce. A society may discourage fertility, and then later, when it seeks to encourage fertility, it may find that people are not used to having large families anymore. Social norms and material realities may have changed in such a way that having large families has become difficult.

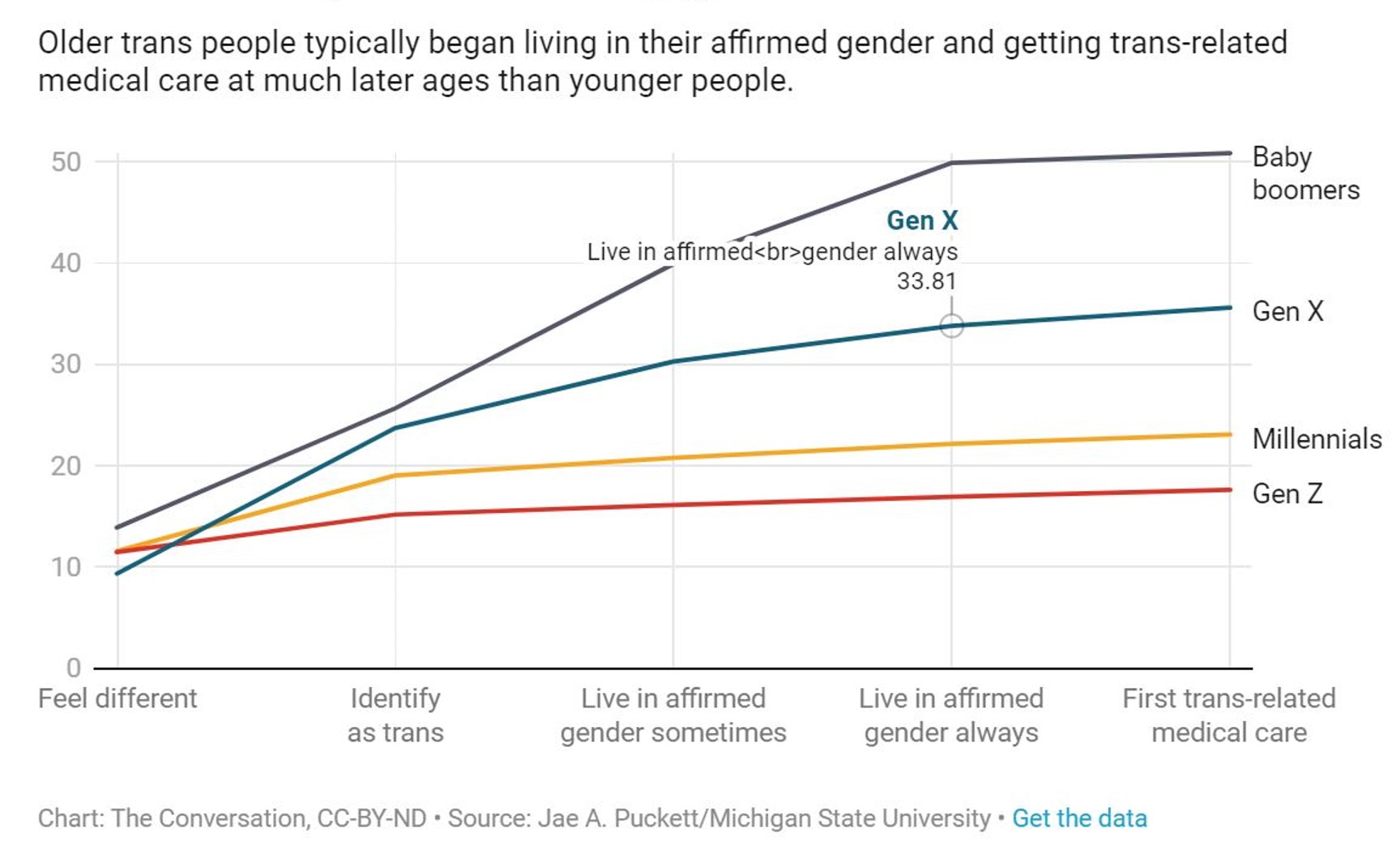

Fertility intentions may be thwarted by decisions which were taken when younger. Of special note is the decision to undergo hormone treatment or gender-affirming surgery. In order to have biological children, trans persons may need cryopreservation of eggs or sperm, fertility treatments, and/or a surrogate mother to bear the child. Many of these measures are expensive.

Given that the age of people who are coming out as transgender and undergoing transitions is becoming younger, as shown in Figure 12-1, we should ask whether adequate consideration is being given to the possibility of wanting to have children later in life.

A “fertility gap” is sometimes measured, which is the difference between the number of children people say they desire to have, and the number they actually end up having.

Although non-economic factors like secularization and social trends seem to have the greatest influence on family size, we will take time to look at economic influences.

The cost of children

Children are born helpless. Even before a child is born, the pregnant mother must make lifestyle and work changes to keep the child safe. Prenatal care is important for mother and baby. Birth is a difficult process which as recently as 1900 gave American women a 0.6-0.9% of dying.[3].

After birth, babies require frequent and careful feeding, diapering, and safekeeping. Lively and meaningful interaction with adults is extremely important to their emotional and intellectual development. Traditionally, the (reproductive) mother has taken on most of this work. Other traditionally female work includes cooking, cleaning, care of relatives and community members, arranging celebrations, keeping in touch with family and friends, and purchasing household goods and gifts.

This traditional female role is often deeply fulfilling and freely chosen. It also delays, complicates, and interrupts education and workplace careers. Claudia Goldin, who won the Nobel Economics prize in 2023, has studied the male-female wage gap and believes that child-related career disruption is its most important explanation of the gap.[4]

Men too make sacrifices for their children. People who aspire to the role of traditional father work hard, taking on most of the responsibility for securing the family’s income. They see most of their earnings go to the family’s needs, and they defend the family and the nation from danger, even at the cost of their own lives.

Modern parents need not and typically do not completely conform to traditional roles, but as a parental unit they must figure out how best to care for their children. From infancy to young adulthood, and even beyond, children benefit from the time, attention, and money that parents provide.

Duncan, Frank and Guevremont (2023) reported that, based on behaviour recorded between 2014 and 2017, Canadian parents spend about $293,000 in 2017 dollars in direct costs raising a child from age zero to age seventeen. The lower income group spends $238,190 while the higher income group spends $403,910.

The material costs of raising children have risen over the years as standards of care have risen. It is now normal for western children to have multiple sets of clothing, music lessons, sports lessons, summer camp experiences, and birthday parties. On the other hand, these things have become more affordable and accessible. Health care, primary education, and high school are all free of charge. The government of Canada offers the Canada Child Care Tax Credit to lower income families, continuing a tradition that began in 1944. Many nations have “baby bonuses” paid to the parents of young children.

Aside from the direct costs of raising children, there is the opportunity cost of raising children. As the career potential of women and other equity-seeking groups has improved, their opportunity cost of raising children has increased. We discuss this in more detail later.

Children providing material benefits

In various times and places, children may have been and continue to be a net material benefit to parents over the lifetime of the parents. Children can work for the family, and children can care for their parents when parents are no longer able to work themselves.

Children of about eight years of age and older have worked in sweatshops and on plantations as long as poverty has existed. Today their tiny fingers weave carpets in Afghanistan and their small bodies wriggle through mining tunnels in Tanzania. They may not be paying their own way, but they are at least contributing to their families’ incomes.

It seems to be generally the case that children cannot earn as much as it costs to look after them, until they are teens. In her book on British children who were (sometimes forcibly) brought to Canada in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, Joy Parr (1980) notes that the child care agency had to pay host families to take children under 11, even if those children worked on the host family’s farm. Becker (1960) mentioned a finding that male slaves were a net expense to American slave owners until those slaves were about 18 years of age.

Whether or not money can be recouped from children before they reach adulthood, adult children can represent a safety net for parents. In societies where healthcare is unsubsidized, insurance is unaffordable, and pensions are inadequate, parents need children to look after them in old age. In such societies, the capital-to-labour ratio is likely to be low, and the returns to additional capital greater than the returns to additional labor. If therefore poor families could have access to bank accounts, could invest in reliable capital markets, could afford insurance, and could contribute to well-managed pension plans, poor families might dare have fewer children, and the nation’s material productivity would likely increase.

In some situations, some parents look at their children as lottery tickets. One of the children might become extremely successful and greatly enhance the family’s standing.

What about the economics of childbearing in more prosperous families, where children do not provide economic security to their parents?

Children providing emotional benefits to their parents

Crude as it may be, the “demand for children” has been modeled for the case where children are a net cost to parents. In these models, children provide “utility” to their parents. Parents maximize utility from children and from other things, within the constraints of a budget and a 24-hour day. The parents’ constrained utility maximization results in a desired number of children as well as a desired amount of alternative goods and leisure opportunities. The key determinants of the demand for children are income, the cost of children, the cost of substitute goods, and the cost of complementary goods. This is a crass, incomplete, but suggestive approach to understanding the fertility decision.

This approach assumes that children are actually “normal goods”, i.e., that more children are preferred as income rises. Is this indeed the case? It seems rather that people and nations choose to have fewer children as incomes rise, suggesting that children are “inferior goods”. Although for some people it may be true that children are inferior goods, the idea that children usually are inferior goods is so unappealing that economists have set out to find a model that can contradict it, a model like that of Willis (1973).

Willis developed a detailed model of parental choice. In Willis’ model, each family has two parents. The parents act as one and maximize utility. Utility depends on N, the number of children; Q, the level of childhood “quality” for each child, and S, an alternative activity such as skiing. Q and S cost both time and money. Q is more time-intensive than S. Parents choose between spending time and money skiing (S) or raising children (N*Q).

Each parental unit also faces constraints. Parents must earn income to pay for skiing and child services, and they have to allocate their limited amount of time. Willis assumes that one of the parents takes on the traditionally male role of working outside the home full-time. We’ll call this parent the “traditional father”. The other parent takes on the traditionally female role of remaining outside the paid workforce when and if the couple decides that children need to be cared for at home. Call this parent the “traditional mother”. Each parent’s wage depends on their initial skill level and their experience in the workforce, but only the traditional mother compares the costs and benefits of staying home with children. Time spent with children means lost wages now and a lower wage in the future.

Note that Willis’ model is not appropriate for a very poor nation. The model assumes that all children survive and that children provide no labour or old age security.

Willis considers that the family might receive a sudden gift of cash, or the father’s wage might rise. This is considered an increase in “endowment income” because it does not require the hours worked to change. The traditional father is already committed to working full-time. If there is an increase in endowment income, and if child services N*Q is a normal good, the parents will want more child services. However, we do not know whether more child services means more children, or more money spent per child. The more the parents spend per child, the more expensive additional children will be, if parents want to treat all children equally. If parents get richer, they might choose to increase Q without increasing N. We can thus have increases in income translating into fewer children without children being “inferior goods”. Mission accomplished.

But what happens if the wage of the traditional mother rises? This may change how much the mother works. On the one hand, the family feels richer; it feels it can afford more N*Q, which will keep the mother busy at home. This is the income effect of the wage change. But on the other hand, children are now effectively more expensive, because they take time, and the opportunity cost of the mother’s time has now risen. This substitution effect makes the family feel it can afford less N*Q.

There is no substitution effect when the (traditional) father’s wage rises, because he was never considering staying at home with kids. But for the (traditional) mother who has the opportunity to work outside the home there is a substitution effect, because time is money and children cost time.

According to Willis’ calculations, the following things make it likely fewer children will be desired:

- a decrease in the cost of skiing or whatever the alternatives to child-rearing are

- an increase in the time or money cost of NQ

- a high desired Q for each child

- any decrease in the traditional male’s lifetime earnings

- an increase in the traditional female’s wage, assuming that child-rearing is more time-consuming than skiing, but less expensive than skiing

Higher wages and improved opportunities for women are likely to decrease the fertility rate, at least initially.

At low and medium wages, the substitution effect is likely more powerful than the income effect. So a wage increase leads the parent to work more and spend less time with children. At high wages the substitution effect may be weaker than the income effect, so that the parent decides to spend more time at home or have more children.

At low and medium wages, the substitution effect is likely more powerful than the income effect. So a wage increase leads the parent to work more and spend less time with children. At high wages the substitution effect may be weaker than the income effect, so that the parent decides to spend more time at home or have more children.

T. Paul Schulz, a famous development economist, wrote that

“There is an inverse association between income per adult and fertility among countries, and across households this inverse association is also often observed. Many studies find fertility is lower among better educated women [implying that the substitution effect outweighs the income effect] and is often higher among women whose families own more land and assets [a pure endowment income effect].”[5]

Myrskyla et al. (2009) suggested that the income effect becomes dominant for countries with high socioeconomic performance. Graphing the total fertility rate against the United Nations’ Human Development Index (HDI)[6] for 240 countries, the authors observed that fertility fell as HDI increased, but only up to a score of about 0.9. For most countries whose HDIs exceed 0.9, TFR increased as the HDI increased. This conclusion has not been firmly established.

Abeysinghe (1993) studied Canadian fertility and used statistical analysis to correlate wages, income, and the number of children. He concluded that when it comes to female wages, the substitution effect outweighed the income effect of a wage increase, and higher female wages meant a lower TFR. On the other hand, there was a pure income effect which favours children: men whose incomes compared favourably to their parents had more children.

Although Abeysinghe found that age-specific fertility rates and the total fertility rate fell when female wages rose, the drop in fertility seemed to be temporary. That is, higher wages caused women to postpone childbearing rather than to avoid childbearing. Tempo-adjusted TFR would not be as sensitive to female wages as TFR itself. Abeysinghe found that the female wage rate was not much correlated with the completed fertility rate.

Not everyone who postpones having kids will find the time or find a partner, or be fertile enough to have kids later. (Recall the “fertility trap”.) However, some of them will be able to have their children later on. Inasmuch as that is the case, TFR underestimates CFR.

If higher wages are associated with fewer children, at least temporarily, we would expect fewer births during economic boom times, and more children during recessions. For example, the New York Times reported in April 2021 that many professional dancers were finding that the cancellation of events due to COVID-19 was giving them the chance to have a baby and then get back into shape.[7] However, fertility usually falls during economic recessions. Mocan (1990) attributes most of this effect to the fact that during economic recessions the age at marriage rises and the divorce rate also rises. Otherwise, he believes, fertility would be slightly higher during recessions and lower during economic expansions.

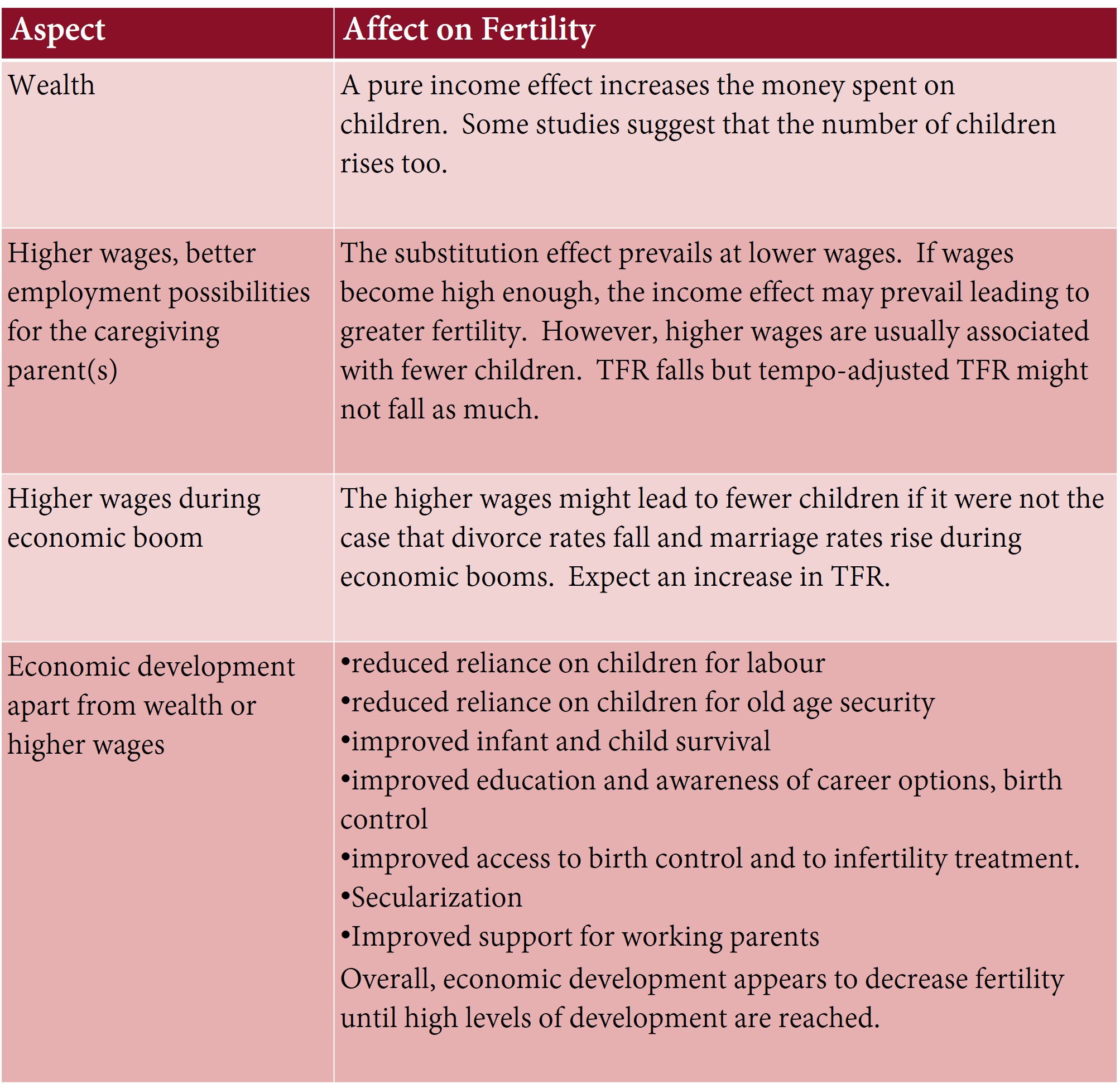

When asked how income affects fertility, we must distinguish between four different aspects of income:

Having considered the factors that affect fertility at the individual, family, and societal level, we will turn to our next chapter to focus on government attempts to control fertility.

- Give one example of how economic conditions can influence each of the three determinants of fertility.

- What is the “fertility trap”?

- How does secularization affect fertility?

- One explanation of the fact that wealthier people have fewer children is that children are “inferior goods”. What other explanations have been offered?

- Explain the effect of the non-caregiving parent’s wage on the caregiving parent’s decision to work.

- in vitro fertilization means uniting an egg and sperm outside the human body, then implanting the embryo inside the would-be mother's uterus. ↵

- a surrogate mother is someone willing to carry a baby from another family in her uterus. ↵

- CDC (1999) ↵

- See for example Bertrand, Goldin, and Katz (2010). ↵

- Schultz (2005) ↵

- HDI is an index of life expectancy at birth, income per person, and education levels achieved ↵

- G. Kourlas, "A Pregnant Pause, in Pandemic Time," New York Times, April 25, 2021. ↵

Birth control comprises many different ways to avoid having children, including abstinence,

contraception, abortion, and sterilization.

Abstinence means not having sexual relations with another person.

Contraception prevents sperm from fertilizing an ovum.

Abortion causes a fertilized egg to fail to implant in the uterus, or it causes an embryo or fetus to die.

Sterilization renders someone incapable of having children. Two medical procedures that accomplish sterilization are tubal ligation (for biological women) and vasectomy (for biological men).

The Fertility Trap is a situation where postponing or discouraging childbearing at one time makes having children more difficult later on, to a degree that was not anticipated.

The fertility gap is the difference in a cohort's self-professed intended fertility rate and their completed fertility rate.

The income effect of a wage change is the degree to which it causes people to feel wealthier and spend more on something.

The substitution effect of a wage change is the degree to which it causes people to feel their time is more valuable. Due to the substitution effect, they will work more and cut back on leisure, child care, or other time-intensive activities.