10.1 Communication

In this section:

Communication

Before we explore different forms of communication, it is important that we have a shared understanding of what we mean by the word communication.

The Communication Process

Interpersonal communication is an important part of being effective in the workplace. It helps us to:

- influence the opinions, attitudes, motivations, and behaviors of others;

- express our feelings, emotions, and intentions to others;

- exchange information regarding events or issues; and

- reinforce the formal structure of the organization by such means as making use of formal channels of communication.

Interpersonal communication allows employees at all levels of an organization to interact with others, to secure desired results, to request or extend assistance, and to make use of and reinforce the formal design of the organization. These purposes serve not only the individuals involved, but the larger goal of improving the quality of organizational effectiveness.

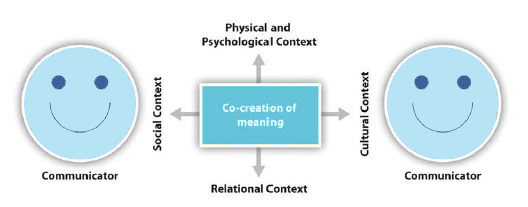

The transactional model that we present here is an oversimplification of what really happens in communication, but this model will be useful in creating a diagram to be used to discuss the topic. Figure 10.1 illustrates a simple communication episode where a communicator encodes a message and a receiver decodes the message (Shannon & Weaver, 1948).

The transactional model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, you don’t just communicate to exchange messages; you communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape your self-concepts, and engage with others in dialogue to create communities. In short, you don’t communicate about your realities; communication helps to construct your realities (and the realities of others).

The roles of sender (source) and receiver in the transaction model of communication differ significantly from the other models. Instead of labeling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are referred to as communicators. Unlike the interaction model, which suggests that participants alternate positions as sender and receiver, the transaction model suggests that you are simultaneously a sender and a receiver. For example, when meeting a new friend, you send verbal messages about your interests and background, your companion reacts nonverbally. You don’t wait until you are done sending your verbal message to start receiving and decoding the nonverbal messages of your new friend. Instead, you are simultaneously sending your verbal message and receiving your friend’s nonverbal messages. This is an important addition to the model because it allows you to understand how you are able to adapt your communication—for example, adapting a verbal message—in the middle of sending it based on the communication you are simultaneously receiving from your communication partner.

Direction of Communication Within Organizations

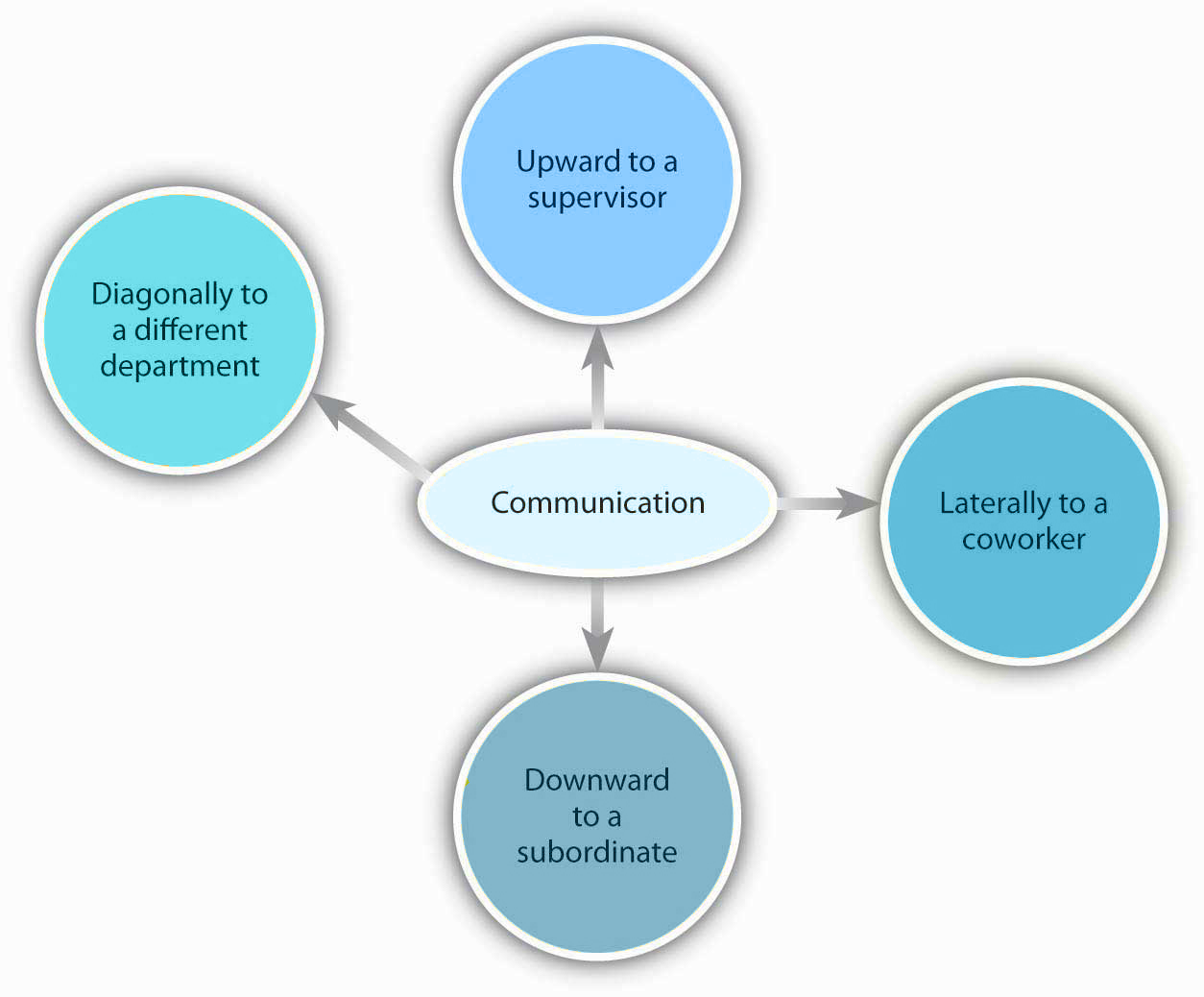

Information can move between communicators in a variety of directions throughout an organization’s hierarchy. It can move laterally through sharing of information between coworkers, diagonally when information is shared between different branches or areas within an organization. Information can also flow upwards or downwards to supervisors and subordinates. Another powerful means of information dissemination in organizations that is not depicted in the image below is an informal network of gossip that travels through an organization often referred to as the grapevine.

Types of Communication

Written Communication

Written communications include e-mail, texts, letters, reports, manuals, and annotations on sticky notes. Written communications may be printed on paper or appear on the screen. Written communication is often asynchronous. That is, the sender can write a message that the receiver can read at any time, unlike a conversation that is carried on in real time. A written communication can also be read by many people (such as all employees in a department or all customers). It’s a “one-to-many” communication, as opposed to a one-to-one conversation. The modern workplace relies increasingly on electronic communications like email. Written communication can serve a good medium for messages, such as a change in a company policy, where precision of language and documentation of the message are important. Written communications is a good medium for conveying facts.

Oral Communication

This consists of all messages or exchanges of information that are spoken, and it’s the most prevalent type of communication. Compared to written communication, oral communication is synchronous and has greater channel richness due to the availability of nonverbal cues in addition to the content of the message. Oral communication is preferable for conveying emotions and is often more appropriate for handling sensitive topics that may occur during conflict. In the next section, we will discuss some common patterns of communication behaviours during conflict.

Nonverbal Communication

It’s not just what we say to others, but also how we say it. Research also shows that 55% of in-person communication comes from nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, body stance, and tone of voice. According to one study, only 7% of a receiver’s comprehension of a message is based on the sender’s actual words, 38% is based on paralanguage (the tone, pace, and volume of speech), and 55% is based on nonverbal cues (body language) (Mehrabian, 1981). To be effective communicators, our body language, appearance, and tone must align with the words we’re trying to convey. Changing the tone of voice in a conversation can incite or diffuse a misunderstanding. Thus, it is important to be aware of our nonverbal messages always, but especially during conflict.

Barriers to Effective Communication

Communicating can be more of a challenge than you think, when you realize the many things that can stand in the way of effective communication. These include filtering, selective perception, information overload, emotional disconnects, lack of source familiarity or credibility, workplace gossip, lies, bribery and coercion, semantics, gender differences, differences in meaning between communicators, biased language, and ineffective listening. It is important to be aware of these barriers and how they might create or escalate a conflict situation.. Let’s examine each of these barriers.

Filtering

Filtering is the distortion or withholding of information to manage a person’s reactions. Some examples of filtering include a manager who keeps her division’s poor sales figures from her boss, the vice president, fearing that the bad news will make them angry. A gatekeeper (the vice president’s assistant, perhaps) who doesn’t pass along a complete message is also filtering. The vice president may delete the e-mail announcing the quarter’s sales figures before reading it, blocking the message before it arrives.

As you can see, filtering prevents members of an organization from getting a complete picture of the way things are. To maximize your chances of sending and receiving effective communications, it’s helpful to deliver a Message in multiple ways and to seek information from multiple sources. In this way, the effect of any one person’s filtering the message will be diminished.

Since people tend to filter bad news more during upward communication, it is also helpful to remember that those below you in an organization may be wary of sharing bad news. One way to defuse the tendency to filter is to reward employees who clearly convey information upward, regardless of whether the news is good and bad. Here are some of the criteria that individuals may use when deciding whether to filter a message or pass it on:

- Past experience: Was the communicator rewarded for passing along news of this kind in the past, or were they criticized?

- Knowledge, perception of the speaker: Has the direct superior made it clear that “no news is good news?”

- Emotional state, involvement with the topic, level of attention: Does the communicator’s fear of failure or criticism prevent them from conveying the message? Is the topic within their realm of expertise, increasing their confidence in their ability to decode it, or is this person out of their comfort zone when it comes to evaluating the message’s significance? Are personal concerns impacting their ability to judge the message’s value?

Once again, filtering can lead to miscommunications in the workplace. Each listener translates the message, creating their own version of what was said (Alessandra, 1993).

Selective Perception

Recall, selective perception refers to filtering what we see and hear to suit our own needs. This process is often unconscious. Small things can command our attention when we’re visiting a new place—a new city or a new company. Over time, however, we begin to make assumptions about the way things are on the basis of our past experience. Often, much of this process is unconscious. “We simply are bombarded with too much stimuli every day to pay equal attention to everything so we pick and choose according to our own needs” (Pope, 2008). Selective perception is a time-saver, a necessary tool in a complex culture. But it can also lead to mistakes. When two selective perceptions collide, a misunderstanding often occurs.

Information Overload

Information overload can be defined as “occurring when the information processing demands on an individual’s time to perform interactions and internal calculations exceed the supply or capacity of time available for such processing (Schick, et. al., 1990).” Messages reach us in countless ways every day. Some are societal—advertisements that we may hear or see in the course of our day. Others are professional—e-mails, and memos, voice mails, and conversations from our colleagues. Others are personal—messages and conversations from our loved ones and friends.

Add these together and it’s easy to see how we may be receiving more information than we can take in. This state of imbalance is known as information overload. Experts note that information overload is “A symptom of the high-tech age, which is too much information for one human being to absorb in an expanding world of people and technology. It comes from all sources including TV, newspapers, and magazines as well as wanted and unwanted regular mail, e-mail and faxes. It has been exacerbated enormously because of the formidable number of results obtained from Web search engines (PC Magazine, 2008; Dawley & Anthony, 2003).” Other research shows that working in such fragmented fashion has a significant negative effect on efficiency, creativity, and mental acuity (Overholt, 2001).

Let’s Focus: Dealing with Information Overload

One of the challenges in many organizations is dealing with a deluge of emails, texts, voicemails, and other communication. Organizations have become flatter, outsourced many functions, and layered technology to speed communication with an integrated communication programs such as Slack, which allows users to manage all their communication and access shared resources in one place. This can lead to information overload, and crucial messages may be drowned out by the volume in your inbox.

One of the challenges in many organizations is dealing with a deluge of emails, texts, voicemails, and other communication. Organizations have become flatter, outsourced many functions, and layered technology to speed communication with an integrated communication programs such as Slack, which allows users to manage all their communication and access shared resources in one place. This can lead to information overload, and crucial messages may be drowned out by the volume in your inbox.

Add the practice of “reply to all,” which can add to the volume of communication, that many coworkers use, and that means that you may get five or six versions of an initial e-mail and need to understand all of the responses as well as the initial communication before responding or deciding that the issue is resolved and no response is needed. Here are suggestions to dealing with e-mail overload upward, horizontally, and downward within your organization and externally to stakeholders and customers.

One way to reduce the volume and the time you spend on e-mail is to turn off the spigot of incoming messages. There are obvious practices that help, such as unsubscribing to e-newsletters or turning off notifications from social media accounts. Also consider whether your colleagues or direct reports are copying you on too many emails as an FYI. If yes, explain that you only need to be updated at certain times or when a final decision is made.

You will also want to set up a system that will organize your inbox into “folders” that will allow you to manage the flow of messages into groups that will allow you to address them appropriately. Your system might look something like this:

Inbox: Treat this as a holding pen. E-mails shouldn’t stay here any longer than it takes for you to file them into another folder. The exception is when you respond immediately and are waiting for an immediate response.

Today: This is for items that need a response today.

This week: This is for messages that require a response before the end of the week.

This month/quarter: This is for everything that needs a longer-term response. Depending on your role, you may need a monthly or quarterly folder.

FYI: This is for any items that are for information only and that you may want to refer back to in the future.

This system prioritizes e-mails based on timescales rather than the e-mails’ senders, enabling you to better schedule work and set deadlines. Another thing to consider is your outgoing e-mail. If your outgoing messages are not specific, too long, unclear, or are copied too widely, your colleagues are likely to follow the same practice when communicating with you. Keep your communication clear and to the point, and managing your outbox will help make your inbound e-mails manageable.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How are you managing your e-mails now? Are you mixing personal and school and work-related e-mails in the same account?

- How would you communicate to a colleague that is sending too many FYI e-mails, sending too may unclear e-mails, or copying too many people on their messages?

Sources: Gallo, A. (2012, February 12). Stop email overload. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2012/02/stop-email-overload-1; Chingel, B. (2018, January 16). How to beat email overload in 2018. CIPHER. https://www.ciphr.com/advice/email-overload/; Seely, M. (2017, November 6). At the mercy of your inbox? How to cope with email overload. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/small-business-network/2017/nov/06/at-the-mercy-of-your-inbox-how-to-cope-with-email-overload.

Emotional Disconnects

Emotional disconnects happen when the communicators are upset, whether about the subject at hand or about some unrelated incident that may have happened earlier. An effective communication requires communicators who are open to speaking and listening to one another, despite possible differences in opinion or personality. One or both parties may have to put their emotions aside to achieve the goal of communicating clearly. A communicator who is emotionally upset tends to ignore or distort what the other person is saying. A communicator who is emotionally upset may be unable to present ideas or feelings effectively.

Lack of Source Credibility

Lack of source familiarity or credibility can derail communications, especially when humor is involved. Have you ever told a joke that fell flat? You and the other communicator may lacked the common context that could have made it funny. (Or yes, it could have just been a lousy joke.) Sarcasm and irony are subtle, and potentially hurtful. It’s best to keep these types of communications out of the workplace as their benefits are limited, and their potential dangers are great. Lack of familiarity can lead to misinterpreting humor, especially in less-rich information channels like e-mail.

Similarly, if the communicator lacks credibility or is untrustworthy, the message will not get through. It may create suspicion about the other party’s motivations (“Why am I being told this?”). Likewise, if the communicator has shared erroneous information in the past, or has created false emergencies, the current message may be filtered.

Workplace Gossip

Workplace gossip, also known as the grapevine, is a lifeline for many employees seeking information about their company (Kurland & Pelled, 2000). Researchers agree that the grapevine is an inevitable part of organizational life. Research finds that 70% of all organizational communication occurs at the grapevine level (Crampton, 1998).

Employees trust their peers as a source of messages, but the grapevine’s informal structure can be a barrier to effective communication from the managerial point of view. Its grassroots structure gives it greater credibility in the minds of employees than information delivered through official channels, even when that information is false.

Some downsides of the office grapevine are that gossip offers politically minded insiders a powerful tool for disseminating communication (and self-promoting miscommunications) within an organization. In addition, the grapevine lacks a specific sender, which can create a sense of distrust among employees—who is at the root of the gossip network? When the news is volatile, suspicions may arise as to the person or persons behind the message. Managers who understand the grapevine’s power can use it to send and receive messages of their own. They also decrease the grapevine’s power by sending official messages quickly and accurately, should big news arise.

Lies

In the context of communication, manipulation is the management of facts, ideas or points of view to play upon people’s insecurities or to use emotional appeals to one’s own advantage. Deception is unethical because it uses lies, partial truths, or the omission of relevant information to deceive. No one likes to be lied to or led to believe something that isn’t true. Deception can involve intentional bias or the selection of information to support your position while negatively framing any information that might challenge your audience’s belief.

Deception

We are all familiar with the concept of lying and deception. We are taught from a young age that we should not lie, but we often witness the very people instructing us not to lie engaging in “little white lies” or socially acceptable lies. As communication scholars, we must distinguish between a lie that is told for the benefit of the receiver and a lie that is told with more malicious intent Judee Burgoon and David Buller (1994) define deception as, ‘‘a deliberate act perpetuated by a sender to engender in a receiver beliefs contrary to what the sender believes is true to put the receiver at a disadvantage” (p. 155-156). Deceptive communication can exist in any type of relationship and in any context. H. Dan O’Hair and Michael Cody (1994) discuss deception as a common message strategy that is used in a manner similar to other forms of communication. They state that deception is often purposeful, goal-directed, and can be used as a relational control device. We will begin our discussion of deception by exploring three types of deception. Three types of deception are discussed in the field of communication: falsification, concealment, and equivocation (Burgoon et al., 1996). Falsification is when a source deliberately presents information that is false or fraudulent. Researchers have found that falsification is the most common form of deception. Concealment is another form of deception in which the source deliberately withholds information. The third form of deception is referred to as equivocation. This form of deception represents a moral grey area for some because some see equivocation as a clear lie. Equivocation is a statement that could be interpreted as having more than one meaning.

Coercion and Bribery

Other unethical behaviours include coercion and bribery. Coercion is the use of power to make someone do something they would not choose to do freely. It usually involves threats of punishment. In the short term, coercion can create compliance. However, it can result in dislike and disrespect of the coercing person or group and a toxic work environment that is ruled by fear and other negative emotions. Bribery, which is offering something in return for an expected favour, is similarly unethical because it sidesteps normal, fair protocol for personal gain at the audience’s expense. When the rest of the team finds out that they lost out on opportunities because someone received favours for favours, an atmosphere of mistrust and animosity—hallmarks of a toxic work environment—hangs over the workplace.

Semantics

Semantics is the study of meaning in communication. Words can mean different things to different people, or they might not mean anything to another person. For example, companies often have their own acronyms and buzzwords that are clear to them but impenetrable to outsiders. Given the amount of messages we send and receive every day, it makes sense that humans try to find shortcuts—a way to communicate things in code. In business, this code is known as jargon. Jargon is the language of specialized terms used by a group or profession. It is common shorthand among experts and if used sensibly can be a quick and efficient way of communicating. Most jargon consists of unfamiliar terms, abstract words, nonexistent words, acronyms, and abbreviations, with an occasional euphemism thrown in for good measure. Every profession, trade, and organization has its own specialized terms (Wright, 2008). At first glance, jargon seems like a good thing—a quicker way to send an effective communication, the way text message abbreviations can send common messages in a shorter, yet understandable way. But that’s not always how things happen. Jargon can be an obstacle to effective communication, causing listeners to tune out or fostering ill-feeling between partners in a conversation. When jargon rules the day, the message can get obscured.

A key question to ask before using jargon is, “Who is the my intended audience?” If you are a specialist speaking to another specialist in your area, jargon may be the best way to send a message while forging a professional bond—similar to the way best friends can communicate in code. For example, an information technology (IT) systems analyst communicating with another IT employee may use jargon as a way of sharing information in a way that reinforces the pair’s shared knowledge. But that same conversation should be held in standard English, free of jargon, when communicating with staff members outside the IT group.

Differences in meaning often exist between communicators. “Mean what you say, and say what you mean.” It’s an easy thing to say. Age, education, and cultural background are all factors that influence how a person interprets words. The less we consider our audience, the greater our chances of miscommunication will be. When communication occurs in the cross-cultural context, extra caution is needed given that different words will be interpreted differently across cultures and different cultures have different norms regarding nonverbal communication. Eliminating jargon is one way of ensuring that our words will convey real-world concepts to others. Speaking to our audience, as opposed to about ourselves, is another.

Cultural Differences

Social norms are culturally relative. The words used in politeness rituals in one culture can mean something completely different in another. For example, thank you in American English acknowledges receiving something (a gift, a favor, a compliment), in British English it can mean “yes” similar to American English’s yes, please, and in French merci can mean “no” as in “no, thank you” (Crystal, 2005).

One of the earliest researchers in the area of cultural differences and their importance to communication was a researcher by the name of Edward T. Hall (Hall, 1977). His book Beyond Culture is still considered one of the most influential books for the field of intercultural communication (Rogers et al., 2002). According to Hall, all cultures incorporate both verbal and nonverbal elements into communication. In his 1959 book, The Silent Language, Hall (1981) states, “culture is communication and communication is culture” (p. 186).

One of Hall’s most essential contributions to the field of intercultural communication is the idea of low-context and high-context cultures. The terms “low-context culture” (LCC) and “high-context culture” (HCC) were created by Hall to describe how communication styles differ across cultures. In essence, “in LCC, meaning is expressed through explicit verbal messages, both written and oral. In HCC, on the other hand, intention or meaning can best be conveyed through implicit contexts, including gestures, social customs, silence, nuance, or tone of voice” (Nam, 2015, p. 378). Table 10.1 further explores the differences between low-context and high-context cultures in three general categories: communication, cultural orientation, and business.

Table 10.1 Low-Context vs. High-Context Cultures

| Low-Context | High-Context | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication | Type of Communication | Explicit Communication | Implicit Communication |

| Communication Focus | Focus on Verbal Communication | Focus on Nonverbal Communication | |

| Context of Message | Less Meaningful | Very Meaningful | |

| Politeness | Not Important | Very Important | |

| Approach to People | Direct and Confrontational | Indirect and Polite | |

| Cultural Orientation | Emotions | No Room for Emotions | Emotions Have Importance |

| Approach to Time | Monochromatic | Polychromatic | |

| Time Orientation | Present-Future | Past | |

| In/Out-Groups | Flexible and Transient Grouping Patterns | Strong Distinctions Between In and Out-Groups | |

| Identity | Based on Individual | Based on Social System | |

| Values | Independence and Freedom | Tradition and Social Rules/Norms | |

| Business | Work Style | Individualistic | Team-Oriented |

| Work Approach | Task-Oriented | Relationship-Oriented | |

| Business Approach | Competitive | Cooperative | |

| Learning | Knowledge is Transferable | Knowledge is Situational | |

| Sales Orientation | Hard Sell | Soft Sell | |

| View of Change | Change over Tradition | Tradition over Change | |

| Source: Interpersonal Communication by Jason S. Wrench; Narissra M. Punyanunt-Carter; and Katherine S. Thweatt, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. | |||

Biased Language

Biased language can offend, alienate or stereotype others on the basis of their personal or group affiliation. Effective communication is clear, factual, and goal-oriented. It is also respectful. Language that insults an individual or group based on age, ethnicity, gender, sexual preference, or political beliefs violates public and private standards of decency, ranging from civil rights to corporate regulations. Many companies offer new employees written guides on standards of speech and conduct. These guides, augmented by common sense and courtesy, are solid starting points for effective, respectful workplace communication. Let’s talk in more detail about some types of biased language including polarizing language, gendered language, disrespectful language, and language that contains microaggressions.

Polarizing Language

Philosophers of language have long noted our tendency to verbally represent the world in very narrow ways when we feel threatened (Hayakawa & Hayakawa, 1990). This misrepresents reality and closes off dialogue. Although in our everyday talk we describe things in nuanced and measured ways, quarrels and controversies often narrow our vision, which is reflected in our vocabulary. In order to maintain a civil discourse in which people interact ethically and competently, it has been suggested that we keep an open mind and an open vocabulary.

One feature of communicative incivility is polarizing language, which refers to language that presents people, ideas, or situations as polar opposites. Such language exaggerates differences and overgeneralizes. Things aren’t simply black or white, right or wrong, or good or bad. Being able to only see two values and clearly accepting one and rejecting another doesn’t indicate sophisticated or critical thinking. We don’t have to accept every viewpoint as right and valid, and we can still hold strongly to our own beliefs and defend them without ignoring other possibilities or rejecting or alienating others. In avoiding polarizing language, we keep a more open mind, which may lead us to learn something new. Avoiding polarizing language can help us avoid polarized thinking, and the new information we learn may allow us to better understand and advocate for our position. Avoiding sweeping generalizations allows us to speak more clearly and hopefully avoid defensive reactions from others that result from such blanket statements.

Gender Neutral

Gender-neutral language use is important in a diverse workplace, assumptions should never be made as to what a person’s preferred pronouns or name are. The simplest way to avoid making a mistake when referring to someone else is to use the name they have introduced themselves to you with to refer to them. This avoids the use of pronouns that they do not identify with. Some examples of gender-neutral pronouns that you can use when referring to others are, they, them, and their. These pronouns do not make assumptions about the gender identity. Another way that gender neutral language can be incorporated into our day-to-day communication is by reframing terms that were previously gendered, such as foreman or journeyman. By using the neutral terms foreperson or journeyperson we do not exclude anyone from these titles.

Respectful

Respectful communication is communication that focuses on topics that are appropriate for your audiences, using manners, allowing others the space to speak, and avoiding topics that are inflammatory, insulting or prejudicial. As individuals, we each have our own unique sets of beliefs, opinions and values, however it is not our place to bestow those upon others without their consent, nor to judge others for theirs. When engaging in respectful verbal communication, particularly with those you do not know well, focus on the subject at hand, common interests, and neutral topics. Use manners, say please and thank you when appropriate, be genuine and apologize for miscommunications. Allow the person you are communicating with space to speak, do not interrupt or take over the conversation, wait your turn.

Microaggressions

When engaging in verbal communication you should also be aware of microaggressions, their impact and what can be done to avoid conflict that stems from them. Microaggressions are subtle slights, remarks and actions that occur both consciously and unconsciously and are often linked to our unconscious bias and stereotypes. These remarks are often made based on assumptions and can perpetuate stereotypes of people of other cultures, races, gender identities and sexualities. Sometimes these comments are made in such a way that the person who has made them does not realize they have insulted the other person. These small and seemingly harmless comments and actions are psychologically harmful and have an impact on the overall ability of a work environment to feel inclusive and respectful. It is important to acknowledge our own personal biases and to not allow them to guide our communication with others based on assumptions. Expanding your circles to include a diverse make up of people with whom you interact, being an ally against discrimination and carefully considering your actions and words when interacting with others are keys to avoiding the harm that is created by microaggressions. If you do unknowingly use microaggressions and this is pointed out to you, take the time to listen and acknowledge why this may have been harmful to the other person, do not get defensive about it, and apologize for the comment.

Ineffective Listening

Our final barrier is ineffective listening. A communicator may strive to deliver a message clearly, but the ability to listen effectively is equally vital to effective communication. The average worker spends 55% of their workdays listening. Managers listen up to 70% each day. But listening doesn’t lead to understanding in every case. Listening takes practice, skill, and concentration.

According to University of San Diego professor Phillip Hunsaker, “The consequences of poor listening are lower employee productivity, missed sales, unhappy customers, and billions of dollars of increased cost and lost profits. Poor listening is a factor in low employee morale and increased turnover because employees do not feel their managers listen to their needs, suggestions, or complaints (Alessandra, et. al., 1993).” We will talk more about how to engage in effective listening later in this chapter.

Adapted Works

“Communication Defined” in Psychology, Communication, and the Canadian Workplace by Laura Westmaas, BA, MSc is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Different Types of Communication and Channels” in Organizational Behavior by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Communication Barriers” in Principles of Management by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Cultural Characteristics and Communication” in Exploring Relationship Dynamics by Maricopa Community College District is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

“Language, Society, and Culture” in Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

References

Alessandra, T. (1993). Communicating at work. Fireside.

Burgoon, J. K., & Buller, D. B. (1994). Interpersonal deception: III. Effects of deceit on perceived communication and nonverbal behavior dynamics. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 18, 155–184.

Burgoon, J. K., Buller, D. B., Guerrero, L. K., Afifi, W., & Feldman, C. (1996). Interpersonal deception: XII. Information management dimensions underlying deceptive and truthful messages. Communication Monographs, 63(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637759609376374

Crampton, S. M. (1998). The informal communication network: Factors influencing grapevine activity. Public Personnel Management. http://www.allbusiness.com/management/735210-1.html

Crystal, D. (2005). How language works: How babies babble, words change meaning, and languages live or die. Overlook Press.

Dawley, D. D., & Anthony, W. P. (2003). User perceptions of e-mail at work. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, 17, 170–200.

Hall, E. T. (1977). Beyond culture. Anchor Press.

Hall, E. T. (1981). The silent language. Anchor Books. (Reprint of The Silent Language by E. T. Hall, 1959, Doubleday).

Kurland, N. B., & Pelled, L. H. (2000). Passing the word: Toward a model of gossip and power in the workplace. Academy of Management Review, 25, 428–438.

Mehrabian, A. (1981). Silent messages. Wadsworth.

Nam, K. A. (2015). High-context and low-context communication. In J. M. Bennett (Ed.), The SAGE encyclopedia of intercultural competence (pp. 377-381). Sage.

O’Hair, H. D., & Cody, M. J. (1994). Deception. In W. R. Cupach & B. H. Spitzberg (Eds.), The dark side of interpersonal communication (pp. 181–214). Erlbaum.

Overholt, A. (2001, February). Intel’s got (too much) mail. Fast Company. http://www.fastcompany.com/online/44/intel.html

Pope, R. R. Selective perception. Illinois State University. http://lilt.ilstu.edu/rrpope/rrpopepwd/articles/perception3.html

Rogers, E. M., Hart, W. B., & Mike, Y. (2002). Edward T. Hall and the history of intercultural communication: The United States and Japan. Keio Communication Review, 24, 3–26. http://www.mediacom.keio.ac.jp/publication/pdf2002/review24/2.pdf

Schick, A. G., Gordon, L. A., & Haka, S. (1990). Information overload: A temporal approach. Accounting, Organizations, and Society, 15, 199–220.

Wright, N. (n.d.). Keep it jargon-free. Plain Language Action and Information Network Website. http://www.plainlanguage.gov/howto/wordsuggestions/jargonfree.cfm