2.1 Communication Defined

Communication Defined

Before we explore different forms of communication, it is important that we have a shared understanding of what we mean by the word communication.

This definition builds on other definitions of communication that have been rephrased and refined over many years. In fact, since the systematic study of communication began in colleges and universities a little over one hundred years ago, there have been more than 126 published definitions of communication (Dance & Larson, 1976).

Different Types of Communication

Communication can be categorized into three basic types:

- verbal communication, in which you listen to a person to understand their meaning;

- written communication, in which you read their meaning; and

- nonverbal communication, in which you observe a person and infer meaning.

Each of these forms of communication are important in the workplace and each has its own advantages, disadvantages, and even pitfalls.

1. Verbal Communication

Verbal communications in business take place over the phone or in person. In addition to routine phone calls and in-person conversations, verbal communication is an important tool for creating shared values within organization through storytelling and for communicating in crucial situations. Let’s explore these two examples further.

Storytelling

Storytelling has been shown to be an effective form of verbal communication; it serves an important organizational function by helping to construct common meanings for individuals within the organization. Stories can help clarify key values and help demonstrate how things are done within an organization, and story frequency, strength, and tone are related to higher organizational commitment (McCarthy, 2008). The quality of the stories entrepreneurs tell is related to their ability to secure capital for their firms (Martens et. al., 2007). Stories can serve to reinforce and perpetuate an organization’s culture.

Crucial Conversations

While the process may be the same, high-stakes communications require more planning, reflection, and skill than normal day-to-day interactions at work. Examples of high-stakes communication events include asking for a raise or presenting a business plan to a venture capitalist. In addition to these events, there are also many times in our professional lives when we have crucial conversations—discussions where not only the stakes are high but also where opinions vary and emotions run strong (Patterson et. al., 2002). One of the most consistent recommendations from communications experts is to work toward using “and” instead of “but” as you communicate under these circumstances. In addition, be aware of your communication style and practice flexibility; it is under stressful situations that communication styles can become the most rigid.

2. Written Communication

In contrast to verbal communications, written business communications are printed messages. Most jobs involve some degree of writing. Examples of written communications include memos, proposals, e-mails, letters, training manuals, and operating policies. They may be printed on paper, handwritten, or appear on the screen. Normally, a verbal communication takes place in real time. Written communication, by contrast, can be constructed over a longer period of time. Written communication is often asynchronous (occurring at different times). A written communication can also be read by many people (such as all employees in a department or all customers). It’s a “one-to-many” communication, as opposed to a one-to-one verbal conversation. There are exceptions, of course: a voicemail is an oral message that is asynchronous. Conference calls and speeches are oral one-to-many communications, and e-mails may have only one recipient or many.

3. Nonverbal Communication

What you say is a vital part of any communication. But what you don’t say can be even more important. Research also shows that 55% of in-person communication comes from nonverbal cues like facial expressions, body stance, and tone of voice. According to one study, only 7% of comprehension is based on the the person’s actual words; 38% is based on paralanguage (the tone, pace, and volume of speech), and 55% is based on nonverbal cues (body language) (Mehrabian, 1981).

Research shows that nonverbal cues can also affect whether you get a job offer. Judges examining videotapes of actual applicants were able to assess the social skills of job candidates with the sound turned off. They watched the rate of gesturing, time spent talking, and formality of dress to determine which candidates would be the most successful socially on the job (Gifford et. al., 1985). For this reason, it is important to consider how we appear in business as well as what we say. The muscles of our faces convey our emotions. We can send a silent message without saying a word. A change in facial expression can change our emotional state. Before an interview, for example, if we focus on feeling confident, our face will convey that confidence to an interviewer. Adopting a smile (even if we’re feeling stressed) can reduce the body’s stress levels.

To be effective communicators, we need to align our body language, appearance, and tone with the words we’re trying to convey. Research shows that when individuals are lying, they are more likely to blink more frequently, shift their weight, and shrug (Siegman, 1985).

Another element of nonverbal communication is tone. A different tone can change the perceived meaning of a message demonstrates how clearly this can be true, whether in verbal or written communication. If we simply read these words without the added emphasis, we would be left to wonder, but the emphasis shows us how the tone conveys a great deal of information. Now you can see how changing one’s tone of voice or writing can incite or defuse a misunderstanding.

Consider This

Consider This

Don’t Use That Tone with Me!

Examples of Tone. Changing your tone can dramatically change your meaning

| Placement of the emphasis | What it means |

|---|---|

| I did not tell John you were late. | Someone else told John you were late. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | This did not happen. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I may have implied it. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | But maybe I told Sharon and José. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I was talking about someone else. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I told him you still are late. |

| I did not tell John you were late. | I told him you were attending another meeting. |

Source: Based on ideas in Kiely, M. (1993, October). When “no” means “yes.” Marketing, 7–9.

In addition to tone of voice, here are a few examples of nonverbal cues that can support or detract from a communicator’s message:

Body Language

A simple rule of thumb is that simplicity, directness, and warmth convey sincerity. And sincerity is key to effective communication. A firm handshake, given with a warm, dry hand, is a great way to establish trust. A weak, clammy handshake conveys a lack of trustworthiness. Gnawing one’s lip conveys uncertainty. A direct smile conveys confidence.

Eye Contact

In business, the style and duration of eye contact considered appropriate vary greatly across cultures. In North American, looking someone in the eye (for about a second) is considered a sign of trustworthiness.

Facial Expressions

The human face can produce thousands of different expressions. These expressions have been decoded by experts as corresponding to hundreds of different emotional states (Ekman et. al., 2008). Our faces convey basic information to the outside world. Happiness is associated with an upturned mouth and slightly closed eyes; fear with an open mouth and wide-eyed stare. Flitting (“shifty”) eyes and pursed lips convey a lack of trustworthiness. The effect of facial expressions in conversation is instantaneous. Our brains may register them as “a feeling” about someone’s character.

Posture

The position of our body relative to a chair or another person is another powerful silent messenger that conveys interest, aloofness, professionalism—or lack thereof. Head up, back straight (but not rigid) implies an upright character. In interview situations, experts advise mirroring an interviewer’s tendency to lean in and settle back in her seat. The subtle repetition of the other person’s posture conveys that we are listening and responding.

Touch

The meaning of a simple touch differs between individuals, genders, and cultures. In Mexico, when doing business, men may find themselves being grasped on the arm by another man. To pull away is seen as rude. In Indonesia, to touch anyone on the head or touch anything with one’s foot is considered highly offensive. Canadians often place great value in a firm handshake. But handshaking as a competitive sport (“the bone-crusher”) can come off as needlessly aggressive, at home and abroad.

Space

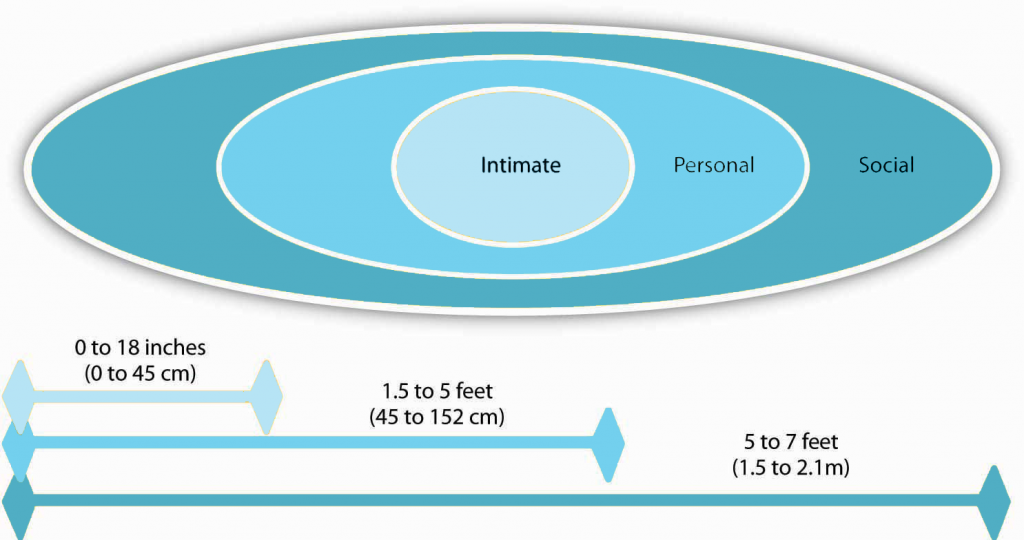

Anthropologist Edward T. Hall coined the term proxemics to denote the different kinds of distance that occur between people. These distances vary between cultures. The figure below outlines the basic proxemics of everyday life and their meaning (Hall, 1966):

Standing too far away from a colleague (such as a public speaking distance of more than seven feet) or too close to a colleague (intimate distance for embracing) can thwart an effective verbal communication in business.

Let’s Review

Let’s Review

- Types of communication include verbal, written, and nonverbal.

- Verbal communications have the advantage of immediate feedback, are best for conveying emotions, and can involve storytelling and crucial conversations.

- Written communications have the advantage of asynchronicity, of reaching many readers, and are best for conveying information.

- Both verbal and written communications convey nonverbal messages through tone; verbal communications are also colored by body language, eye contact, facial expression, posture, touch, and space.

Exercises

Exercises

- When you see a memo or e-mail full of typos, poor grammar, or incomplete sentences, how do you react? Does it affect your perception of the sender? Why or why not?

- How aware of your own body language are you? Has your body language ever gotten you into trouble when you were communicating with someone?

- If the meaning behind verbal communication is only 7% words, what does this imply for written communication?

References

This section is adapted from:

Communication in the Real World by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Principles of Management for Leadership Communication by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

Dance, F. E. X., & Larson, C. E. (1976). The functions of human communication: A theoretical approach. Holt, Reinhart, and Winston.

Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Hager, J. C. (2008). The facial action coding system (FACS). http://face-and-emotion.com/dataface/facs/manual.

Gifford, R., Ng, C. F., & Wilkinson, M. (1985). Nonverbal cues in the employment interview: Links between applicant qualities and interviewer judgments. Journal of Applied Psychology, 70, 729–736.

Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension. Doubleday.

Martens, M. L., Jennings, J. E., & Devereaux, J. P. (2007). Do the stories they tell get them the money they need? The role of entrepreneurial narratives in resource acquisition. Academy of Management Journal, 50, 1107–1132.

McCarthy, J. F. (2008). Short stories at work: Storytelling as an indicator of organizational commitment. Group & Organization Management, 33, 163–193.

Mehrabian, A. (1981). Silent messages. Wadsworth.

Patterson, K., Grenny, J., McMillan, R., & Switzler, A. (2002). Crucial conversations: Tools for talking when stakes are high. McGraw-Hill.

Siegman, A. W. (1985). Multichannel integrations of nonverbal behavior. Lawrence Erlbaum.